The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). It was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China. The World Health Organization declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern in January 2020 and a pandemic in March 2020. As of 8 January 2021, more than 88 million cases have been confirmed, with more than 1.89 million deaths attributed to COVID-19.

Symptoms of COVID-19 are highly variable, ranging from none to severe illness. The virus spreads mainly through the air when people are near each other. It leaves an infected person as they breathe, cough, sneeze, or speak and enters another person via their mouth, nose, or eyes. It may also spread via contaminated surfaces. People remain infectious for up to two weeks, and can spread the virus even if they do not show symptoms.

Recommended preventive measures include social distancing, wearing face masks in public, ventilation and air-filtering, hand washing, covering one’s mouth when sneezing or coughing, disinfecting surfaces, and monitoring and self-isolation for people exposed or symptomatic. Several vaccines are being developed and distributed. Current treatments focus on addressing symptoms while work is underway to develop therapeutic drugs that inhibit the virus. Authorities worldwide have responded by implementing travel restrictions, lockdowns, workplace hazard controls, and facility closures. Many places have also worked to increase testing capacity and trace contacts of the infected.

The responses to the pandemic have resulted in global social and economic disruption, including the largest global recession since the Great Depression. It has led to the postponement or cancellation of events, widespread supply shortages exacerbated by panic buying, agricultural disruption and food shortages, and decreased emissions of pollutants and greenhouse gases. Many educational institutions have been partially or fully closed. Misinformation has circulated through social media and mass media. There have been incidents of xenophobia and discrimination against Chinese people and against those perceived as being Chinese or as being from areas with high infection rates.

Epidemiology

| For country-level data, see: | |

|

COVID-19 pandemic by country and territory

|

|

Cases

88,005,213 Deaths

1,897,568 As of 8 January 2021

|

|

|

Africa · Asia · Europe · North America

Oceania · South America |

Background

Although it is still unknown exactly where the outbreak first started, many early cases of COVID-19 have been attributed to people who have visited the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, located in Wuhan, Hubei, China. On 11 February 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) named the disease “COVID-19”, which is short for coronavirus disease 2019. The virus that caused the outbreak is known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a newly discovered virus closely related to bat coronaviruses, pangolin coronaviruses, and SARS-CoV. Scientific consensus is that COVID-19 likely originated naturally, probably from bats.

The earliest known person with symptoms was later discovered to have fallen ill on 1 December 2019, and that person did not have visible connections with the later wet market cluster. However, an earlier case of infection could have occurred on 17 November. Of the early cluster of cases reported that month, two thirds were found to have a link with the market. There are several theories about when and where the very first case (the so-called patient zero) originated. It is possible that the virus first emerged in October 2019.

Cases

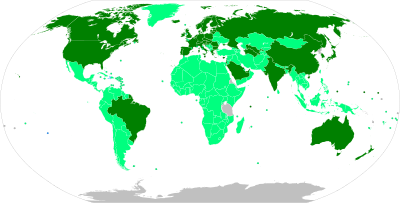

Total confirmed cases per country as of 5 January 2021.

-

10,000,000+

-

1,000,000–9,999,999

-

100,000–999,999

-

10,000–99,999

-

1,000–9,999

-

100–999

-

1–99

-

0

Official case counts refer to the number of people who have been tested for COVID-19 and whose test has been confirmed positive according to official protocols. Many countries, early on, had official policies to not test those with only mild symptoms. An analysis of the early phase of the outbreak up to 23 January estimated 86 percent of COVID-19 infections had not been detected, and that these undocumented infections were the source for 79 percent of documented cases. Several other studies, using a variety of methods, have estimated that numbers of infections in many countries are likely to be considerably greater than the reported cases.

On 9 April 2020, preliminary results found that 15 percent of people tested in Gangelt, the centre of a major infection cluster in Germany, tested positive for antibodies. Screening for COVID-19 in pregnant women in New York City, and blood donors in the Netherlands, has also found rates of positive antibody tests that may indicate more infections than reported. Seroprevalence based estimates are conservative as some studies shown that persons with mild symptoms do not have detectable antibodies. Some results (such as the Gangelt study) have received substantial press coverage without first passing through peer review.

Analysis by age in China indicates that a relatively low proportion of cases occur in individuals under 20. It was not clear whether this was because young people were less likely to be infected, or less likely to develop serious symptoms and seek medical attention and be tested. A retrospective cohort study in China found that children and adults were just as likely to be infected.

Initial estimates of the basic reproduction number (R0) for COVID-19 in January were between 1.4 and 2.5, but a subsequent analysis concluded that it may be about 5.7 (with a 95 percent confidence interval of 3.8 to 8.9). R0 can vary across populations and is not to be confused with the effective reproduction number (commonly just called R), which takes into account effects such as social distancing and herd immunity. By mid-May 2020, the effective R was close to or below 1.0 in many countries, meaning the spread of the disease in these areas at that time was stable or decreasing.

-

Epidemic curve of daily new cases of COVID-19 (7 day rolling average) by continent

-

Semi-log plot of weekly new cases of COVID-19 in the world and top five current countries (mean with deaths)

-

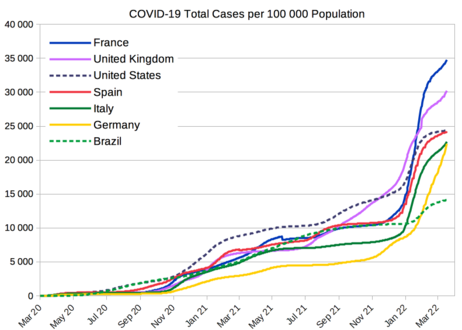

COVID-19 total cases per 100 000 population from selected countries

-

COVID-19 active cases per 100 000 population from selected countries

Deaths

Deceased in a 16 m (53 ft) “mobile morgue” outside a hospital in Hackensack, New Jersey

Official deaths from COVID-19 generally refer to people who died after testing positive according to protocols. This may ignore deaths of people who die without having been tested. Conversely, deaths of people who had underlying conditions may lead to over-counting. Comparison of statistics for deaths for all causes versus the seasonal average indicates excess mortality in many countries. This may include deaths due to strained healthcare systems and bans on elective surgery. The first confirmed death was in Wuhan on 9 January 2020. The first reported death outside of China occurred on 1 February in the Philippines, and the first reported death outside Asia was in the United States on 6 February.

More than 95 percent of the people who contract COVID-19 recover. Otherwise, the time between symptoms onset and death usually ranges from 6 to 41 days, typically about 14 days. As of 8 January 2021, more than 1.89 million deaths had been attributed to COVID-19. People at the greatest risk from COVID-19 tend to be those with underlying conditions, such as a weakened immune system, serious heart or lung problems, severe obesity, or the elderly.

On 24 March 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the United States, indicated the World Health Organization (WHO) had provided two codes for COVID-19: U07.1 when confirmed by laboratory testing and U07.2 for clinically or epidemiological diagnosis where laboratory confirmation is inconclusive or not available. The CDC noted that “Because laboratory test results are not typically reported on death certificates in the U.S., is not planning to implement U07.2 for mortality statistics” and that U07.1 would be used “If the death certificate reports terms such as ‘probable COVID-19’ or ‘likely COVID-19’.” The CDC also noted “It Is not likely that NCHS will follow up on these cases” and while the “underlying cause depends upon what and where conditions are reported on the death certificate, … the rules for coding and selection of the … cause of death are expected to result in COVID–19 being the underlying cause more often than not.”

On 16 April 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO), in its formal publication of the two codes, U07.1 and U07.2, “recognized that in many countries detail as to the laboratory confirmation… will not be reported recommended, for mortality purposes only, to code COVID-19 provisionally to code U07.1 unless it is stated as ‘probable’ or ‘suspected’.” It was also noted that the WHO “does not distinguish” between infection by SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19.

Multiple measures are used to quantify mortality. These numbers vary by region and over time, influenced by testing volume, healthcare system quality, treatment options, government response, time since the initial outbreak, and population characteristics, such as age, sex, and overall health. Countries like Belgium include deaths from suspected cases of COVID-19, regardless of whether the person was tested, resulting in higher numbers compared to countries that include only test-confirmed cases.

The death-to-case ratio reflects the number of deaths attributed to COVID-19 divided by the number of diagnosed cases within a given time interval. Based on Johns Hopkins University statistics, the global death-to-case ratio is 2.2 percent (1,897,568 deaths for 88,005,213 cases) as of 8 January 2021. The number varies by region.

-

Semi-log plot of weekly deaths due to COVID-19 in the world and top five current countries (mean with cases)

-

COVID-19 deaths per 100 000 population from selected countries

Infection fatality ratio (IFR)

A crucial metric in assessing the severity of a disease is the infection fatality ratio (IFR), which is the cumulative number of deaths attributed to the disease divided by the cumulative number of infected individuals (including asymptomatic and undiagnosed infections) as measured or estimated as of a specific date. Epidemiologists frequently refer to this metric as the ‘infection fatality rate’ to clarify that it is expressed in percentage points (not as a decimal). Other published studies refer to this metric as the ‘infection fatality risk’.

In March, a peer-reviewed analysis of pre-serology data from mainland China yielded an overall IFR of 0.66% (with age-bracketed values ranging from 0.00161% for 0–9 years to 0.595% for 50–59 years to 7.8% for > 80 years).

In April 2020, an IFR range of 0.12–1.08% was derived from non-peer-reviewed serology surveys, with the upper bound characterized as much more credible and the range indicated as from 3 to 27 times deadlier than influenza (0.04%).

In July 2020, the US CDC adopted the IFR as a “more directly measurable parameter for disease severity for COVID-19” and computed an overall ‘best estimate’ for planning purposes for the U.S. of 0.65%.

In September, the CDC computed an age-bracketed ‘best estimate’ for the U.S. of 0.003% for 0–19 years; 0.02% for 20–49 years; 0.5% for 50–69 years; and 5.4% for 70+ years. The range of CDC estimates for each age group were as follows.

| Age group | IFR |

|---|---|

| 0–19 | 0.002%–0.01% |

| 20–49 | 0.007%–0.03% |

| 50–69 | 0.25%–1.0% |

| 70+ | 2.8%–9.3% |

In August 2020, the WHO reported serology testing for three locations in Europe (with some data through 2 June) that showed IFR overall estimates converging at approximately 0.5–1%. A systematic review article in The BMJ advised that “caution is warranted … using serological tests for … epidemiological surveillance” and called for higher quality studies assessing accuracy with reference to a standard of “RT-PCR performed on at least two consecutive specimens, and, when feasible, includ viral cultures.” CEBM researchers have called for in-hospital ‘case definition’ to record “CT lung findings and associated blood tests” and for the WHO to produce a “protocol to standardise the use and interpretation of PCR” with continuous re-calibration.

| Coronavirus |

|---|

|

In September 2020, a Bulletin of the World Health Organization article by John Ioannidis estimated the median global IFR inferred from seroprevalence data at 0.23% overall (with rates of 0.09% in areas with low mortality, and 0.57% in areas with high mortality) and 0.05% for people < 70 years (a range of 0.00–0.31%), much lower than estimates made earlier in the pandemic.

On 6 October 2020, Dr. Mike Ryan, director of the WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme announced “Our current best estimates tell us that about 10% of the global population may have been infected by this virus.” Also in October, the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) reported a ‘presumed estimate’ of global IFR at between 0.10% to 0.35%, noting that this will vary between populations due to differences in demographics. These researchers noted a decrease in IFR in England over time; and, for the UK and Italy (the two Europeans nations worst hit by COVID-19), attribute the rise in daily cases, stability in daily deaths, and shift of cases to a younger population to waning viral circulation, misapplication of testing, and misinterpretation of test results rather than to prevention, treatment, or virus mutation.

In November 2020, a review article in Nature reported estimates of population-weighted IFRs for a number of countries, excluding deaths in elderly care facilities, and found a median range of 0.24% to 1.49%.

In December 2020, a systematic review and meta-analysis published in the European Journal of Epidemiology estimated that population-weighted IFR was 0.5% to 1% in some countries (France, Netherlands, New Zealand, and Portugal), 1% to 2% in several other countries (Australia, England, Lithuania, and Spain), and about 2.5% in Italy; these estimates included fatalities in elderly care facilities. This study also found that most of the differences in IFR across locations reflected corresponding differences in the age composition of the population and the age-specific pattern of infection rates, due to very low IFRs for children and younger adults (e.g., 0.002% at age 10 and 0.01% at age 25) and progressively higher IFRs for older adults (0.4% at age 55, 1.4% at age 65, 4.6% at age 75, and 15% at age 85). These results were also highlighted in a December 2020 report issued by the World Health Organization.

Case fatality ratio (CFR)

Another metric in assessing death rate is the case fatality ratio (CFR), which is deaths attributed to disease divided by individuals diagnosed to-date. This metric can be misleading because of the delay between symptom onset and death and because testing focuses on individuals with symptoms (and particularly on those manifesting more severe symptoms). On 4 August, WHO indicated “at this early stage of the pandemic, most estimates of fatality ratios have been based on cases detected through surveillance and calculated using crude methods, giving rise to widely variable estimates of CFR by country – from less than 0.1% to over 25%.”

Disease

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of COVID-19 are variable, ranging from mild symptoms to severe illness. Common symptoms include headache, loss of smell and taste, nasal congestion and rhinorrhea, cough, muscle pain, sore throat, fever and breathing difficulties. People with the same infection may have different symptoms, and their symptoms may change over time. In people without prior ears, nose, and throat disorders, loss of taste combined with loss of smell is associated with COVID-19 with a specificity of 95%.

Most people (81%) develop mild to moderate symptoms (up to mild pneumonia), while 14% develop severe symptoms (dyspnea, hypoxia, or more than 50% lung involvement on imaging) and 5% of patients suffer critical symptoms (respiratory failure, shock, or multiorgan dysfunction). Around one in five people are infected with the virus but do not develop noticeable symptoms at any point in time. These asymptomatic carriers tend not to get tested, and they can spread the disease. Other infected people will develop symptoms later (called pre-symptomatic) or have very mild symptoms, and can also spread the virus.

As is common with infections, there is a delay, known as the incubation period, between the moment a person first becomes infected and the appearance of the first symptoms. The median incubation period for COVID-19 is four to five days. Most symptomatic people experience symptoms within two to seven days after exposure, and almost all symptomatic people will experience one or more symptoms before day twelve.

Transmission

COVID-19 spreads from person to person mainly through the respiratory route after an infected person coughs, sneezes, sings, talks or breathes. A new infection occurs when virus-containing particles exhaled by an infected person, either respiratory droplets or aerosols, get into the mouth, nose, or eyes of other people who are in close contact with the infected person. During human-to-human transmission, an average 1000 infectious SARS-CoV-2 virions are thought to initiate a new infection.

The closer people interact, and the longer they interact, the more likely they are to transmit COVID-19. Closer distances can involve larger droplets (which fall to the ground) and aerosols, whereas longer distances only involve aerosols. The larger droplets may also evaporate into the aerosols (known as droplet nuclei). The relative importance of the larger droplets and the aerosols is not clear as of November 2020, however the virus is not known to transmit between rooms over long distances such as through air ducts. Airborne transmission is able to particularly occur indoors, in high risk locations, such as in restaurants, choirs, gyms, nightclubs, offices, and religious venues, often when they are crowded or less ventilated. It also occurs in healthcare settings, often when aerosol-generating medical procedures are performed on COVID-19 patients.

The number of people generally infected by one infected person varies; as of September 2020 it was estimated that one infected person will, on average, infect between two and three other people. This is more infectious than influenza, but less so than measles. It often spreads in clusters, where infections can be traced back to an index case or geographical location. There is a major role of “super-spreading events”, where many people are infected by one person.

Cause

Illustration of SARSr-CoV virion

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the respiratory illness responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. Colloquially known as simply the coronavirus, it was previously referred to by its provisional name, 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), and has also been called human coronavirus 2019 (HCoV-19 or hCoV-19).

Epidemiological studies estimate each infection results in 5.7 new ones when no members of the community are immune and no preventive measures taken. The virus primarily spreads between people through close contact and via respiratory droplets produced from coughs or sneezes. It mainly enters human cells by binding to the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).

Diagnosis

Demonstration of a swab for COVID-19 testing

Prevention

The CDC and WHO advise that masks reduce the spread of coronavirus by asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic individuals (Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen pictured wearing a surgical mask)

Infographic by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), describing how to stop the spread of germs

Preventive measures to reduce the chances of infection include staying at home, wearing a mask in public, avoiding crowded places, keeping distance from others, ventilating indoor spaces, washing hands with soap and water often and for at least 20 seconds, practising good respiratory hygiene, and avoiding touching the eyes, nose, or mouth with unwashed hands. Those diagnosed with COVID-19 or who believe they may be infected are advised by the CDC to stay home except to get medical care, call ahead before visiting a healthcare provider, wear a face mask before entering the healthcare provider’s office and when in any room or vehicle with another person, cover coughs and sneezes with a tissue, regularly wash hands with soap and water and avoid sharing personal household items.

The first COVID-19 vaccine was granted regulatory approval on 2 December by the UK medicines regulator MHRA. It was evaluated for emergency use authorization (EUA) status by the US FDA, and in several other countries. Initially, the US National Institutes of Health guidelines do not recommend any medication for prevention of COVID-19, before or after exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, outside the setting of a clinical trial. Without a vaccine, other prophylactic measures, or effective treatments, a key part of managing COVID-19 is trying to decrease and delay the epidemic peak, known as “flattening the curve”. This is done by slowing the infection rate to decrease the risk of health services being overwhelmed, allowing for better treatment of current cases, and delaying additional cases until effective treatments or a vaccine become available.

Vaccines

Map of countries by approval status

By mid-December 2020, 57 vaccine candidates were in clinical research, including 40 in Phase I–II trials and 17 in Phase II–III trials. In Phase III trials, several COVID-19 vaccines demonstrated efficacy as high as 95% in preventing symptomatic COVID-19 infections. National regulatory authorities have approved six vaccines for public use: two RNA vaccines (tozinameran from Pfizer–BioNTech and mRNA-1273 from Moderna), two conventional inactivated vaccines (BBIBP-CorV from Sinopharm and CoronaVac from Sinovac), and two viral vector vaccines (Gam-COVID-Vac from the Gamaleya Research Institute and AZD1222 from the University of Oxford and AstraZeneca).

Many countries have implemented phased distribution plans that prioritize those at highest risk of complications such as the elderly and those at high risk of exposure and transmission such as healthcare workers. As of 5 January 2021, 14.5 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine had been administered worldwide based on official reports from national health agencies. Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca predicted a manufacturing capacity of 5.3 billion doses in 2021, which could be used to vaccinate about 3 billion people (as the vaccines require two doses for a protective effect against COVID-19). By December, more than 10 billion vaccine doses had been preordered by countries, with about half of the doses purchased by high-income countries comprising only 14% of the world’s population.

On 4 February 2020, US Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar published a notice of declaration under the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act for medical countermeasures against COVID‑19, covering “any vaccine, used to treat, diagnose, cure, prevent, or mitigate COVID‑19, or the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 or a virus mutating therefrom”, and stating that the declaration precludes “liability claims alleging negligence by a manufacturer in creating a vaccine, or negligence by a health care provider in prescribing the wrong dose, absent willful misconduct”. The declaration is effective in the United States through 1 October 2024. On 8 December it was reported that the AstraZeneca vaccine is about 70% effective, according to a study.

Treatment

An exhausted anesthesiologist physician in Pesaro, Italy, March 2020

Antiviral medications are under investigation for COVID-19, though none have yet been shown to be clearly effective on mortality in published randomized controlled trials.

Emergency use authorization for remdesivir was granted in the U.S. on 1 May, for people hospitalized with severe COVID-19. The interim authorization was granted considering the lack of other specific treatments, and that its potential benefits appear to outweigh the potential risks. In September 2020, following a review of later research, the WHO recommended that remdesivir not be used for any cases of COVID-19, as there was no good evidence of benefit.

Prognosis

The severity of COVID-19 varies. The disease may take a mild course with few or no symptoms, resembling other common upper respiratory diseases such as the common cold. In 3-4% of cases (7.4% for those over age 65) symptoms are severe enough to cause hospitalization. Mild cases typically recover within two weeks, while those with severe or critical diseases may take three to six weeks to recover. Among those who have died, the time from symptom onset to death has ranged from two to eight weeks. The Italian Istituto Superiore di Sanità reported that the median time between the onset of symptoms and death was twelve days, with seven being hospitalised. However, people transferred to an ICU had a median time of ten days between hospitalisation and death. Prolonged prothrombin time and elevated C-reactive protein levels on admission to the hospital are associated with severe course of COVID-19 and with a transfer to ICU.

Some early studies suggest 10% to 20% of people with COVID-19 will experience symptoms lasting longer than a month. A majority of those who were admitted to hospital with severe disease report long-term problems including fatigue and shortness of breath. On 30 October 2020 WHO chief Tedros Adhanom has warned that “to a significant number of people, the COVID virus poses a range of serious long-term effects”. He has described the vast spectrum of COVID-19 symptoms that fluctuate over time as “really concerning.” They range from fatigue, a cough and shortness of breath, to inflammation and injury of major organs – including the lungs and heart, and also neurological and psychologic effects. Symptoms often overlap and can affect any system in the body. Infected people have reported cyclical bouts of fatigue, headaches, months of complete exhaustion, mood swings, and other symptoms. Tedros has concluded that therefore herd immunity is “morally unconscionable and unfeasible”.

Mitigation

Speed and scale are key to mitigation, due to the fat-tailed nature of pandemic risk and the exponential growth of COVID-19 infections. For mitigation to be effective, (a) chains of transmission must be broken as quickly as possible through screening and containment, (b) health care must be available to provide for the needs of those infected, and (c) contingencies must be in place to allow for effective rollout of (a) and (b).

Screening, containment and mitigation

Goals of mitigation include delaying and reducing peak burden on healthcare (flattening the curve) and lessening overall cases and health impact. Moreover, progressively greater increases in healthcare capacity (raising the line) such as by increasing bed count, personnel, and equipment, help to meet increased demand.

Mitigation attempts that are inadequate in strictness or duration—such as premature relaxation of distancing rules or stay-at-home orders—can allow a resurgence after the initial surge and mitigation.

Strategies in the control of an outbreak are screening, containment (or suppression), and mitigation. Screening is done with a device such as a thermometer to detect the elevated body temperature associated with fevers caused by the coronavirus. Containment is undertaken in the early stages of the outbreak and aims to trace and isolate those infected as well as introduce other measures to stop the disease from spreading. When it is no longer possible to contain the disease, efforts then move to the mitigation stage: measures are taken to slow the spread and mitigate its effects on the healthcare system and society. A combination of both containment and mitigation measures may be undertaken at the same time. Suppression requires more extreme measures so as to reverse the pandemic by reducing the basic reproduction number to less than 1.

Part of managing an infectious disease outbreak is trying to delay and decrease the epidemic peak, known as flattening the epidemic curve. This decreases the risk of health services being overwhelmed and provides more time for vaccines and treatments to be developed. Non-pharmaceutical interventions that may manage the outbreak include personal preventive measures such as hand hygiene, wearing face masks, and self-quarantine; community measures aimed at physical distancing such as closing schools and cancelling mass gathering events; community engagement to encourage acceptance and participation in such interventions; as well as environmental measures such surface cleaning.

More drastic actions aimed at containing the outbreak were taken in China once the severity of the outbreak became apparent, such as quarantining entire cities and imposing strict travel bans. Other countries also adopted a variety of measures aimed at limiting the spread of the virus. South Korea introduced mass screening and localised quarantines and issued alerts on the movements of infected individuals. Singapore provided financial support for those infected who quarantined themselves and imposed large fines for those who failed to do so. Taiwan increased face mask production and penalised the hoarding of medical supplies.

Simulations for Great Britain and the United States show that mitigation (slowing but not stopping epidemic spread) and suppression (reversing epidemic growth) have major challenges. Optimal mitigation policies might reduce peak healthcare demand by two-thirds and deaths by half, but still result in hundreds of thousands of deaths and overwhelmed health systems. Suppression can be preferred but needs to be maintained for as long as the virus is circulating in the human population (or until a vaccine becomes available), as transmission otherwise quickly rebounds when measures are relaxed. Long-term intervention to suppress the pandemic has considerable social and economic costs.

Contact tracing

Mandatory traveller information collection for use in COVID-19 contact tracing at New York City’s LaGuardia Airport in August 2020

Contact tracing is an important method for health authorities to determine the source of infection and to prevent further transmission. The use of location data from mobile phones by governments for this purpose has prompted privacy concerns, with Amnesty International and more than a hundred other organisations issuing a statement calling for limits on this kind of surveillance.

Several mobile apps have been implemented or proposed for voluntary use, and as of 7 April 2020 more than a dozen expert groups were working on privacy-friendly solutions such as using Bluetooth to log a user’s proximity to other cellphones. (Users are alerted if they have been near someone who subsequently tests positive.)

On 10 April 2020, Google and Apple jointly announced an initiative for privacy-preserving contact tracing based on Bluetooth technology and cryptography. The system is intended to allow governments to create official privacy-preserving coronavirus tracking apps, with the eventual goal of integration of this functionality directly into the iOS and Android mobile platforms. In Europe and in the U.S., Palantir Technologies is also providing COVID-19 tracking services.

Health care

An army-constructed field hospital outside Östra sjukhuset (Eastern hospital) in Gothenburg, Sweden, contains temporary intensive care units for COVID-19 patients.

Increasing capacity and adapting healthcare for the needs of COVID-19 patients is described by the WHO as a fundamental outbreak response measure. The ECDC and the European regional office of the WHO have issued guidelines for hospitals and primary healthcare services for shifting of resources at multiple levels, including focusing laboratory services towards COVID-19 testing, cancelling elective procedures whenever possible, separating and isolating COVID-19 positive patients, and increasing intensive care capabilities by training personnel and increasing the number of available ventilators and beds. In addition, in an attempt to maintain physical distancing, and to protect both patients and clinicians, in some areas non-emergency healthcare services are being provided virtually.

Due to capacity limitations in the standard supply chains, some manufacturers are 3D printing healthcare material such as nasal swabs and ventilator parts. In one example, when an Italian hospital urgently required a ventilator valve, and the supplier was unable to deliver in the timescale required, a local startup received legal threats due to alleged patent infringement after reverse-engineering and printing the required hundred valves overnight. On 23 April 2020, NASA reported building, in 37 days, a ventilator which is currently undergoing further testing. NASA is seeking fast-track approval.

History

2019

The Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in March 2020, after it was closed down.

Interactive timeline map of confirmed cases per million people

(drag circle to adjust; may not work on mobile devices)

Based on the retrospective analysis, starting from December 2019, the number of COVID-19 cases in Hubei gradually increased, reaching 60 by 20 December and at least 266 by 31 December. That same day, the WHO received reports of a cluster of viral pneumonia cases of an unknown cause in Wuhan, and an investigation was launched at the start of January 2020.

According to official Chinese sources, these early cases were mostly linked to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, which also sold live animals. However, in May 2020, George Gao, the director of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, said animal samples collected from the seafood market had tested negative for the virus, indicating the market was not the source of the initial outbreak.

On 24 December 2019, Wuhan Central Hospital sent a bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) sample from an unresolved clinical case to sequencing company Vision Medicals. On 27 and 28 December, Vision Medicals informed the Wuhan Central Hospital and the Chinese CDC of the results of the test, showing a new coronavirus. A pneumonia cluster of unknown cause was observed on 26 December and treated by the doctor Zhang Jixian in Hubei Provincial Hospital, who informed the Wuhan Jianghan CDC on 27 December.

On 30 December 2019, a test report addressed to Wuhan Central Hospital, from company CapitalBio Medlab, stated that there was an erroneous positive result for SARS, causing a group of doctors at Wuhan Central Hospital to alert their colleagues and relevant hospital authorities of the result. Eight of those doctors, including Li Wenliang (who was also punished on 3 January), were later admonished by the police for spreading false rumours; and another doctor, Ai Fen, was reprimanded by her superiors for raising the alarm. That evening, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission issued a notice to various medical institutions about “the treatment of pneumonia of unknown cause”. The next day, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission made the first public announcement of a pneumonia outbreak of unknown cause, confirming 27 cases—enough to trigger an investigation.

2020

Chinese medics in the city of Huanggang, Hubei on 20 March 2020

During the early stages of the outbreak, the number of cases doubled approximately every seven and a half days. In early and mid-January 2020, the virus spread to other Chinese provinces, helped by the Chinese New Year migration and Wuhan being a transport hub and major rail interchange. On 20 January, China reported nearly 140 new cases in one day, including two people in Beijing and one in Shenzhen. A retrospective official study published in March found that 6,174 people had already developed symptoms by 20 January (most of them would be diagnosed later) and more may have been infected. A report in The Lancet on 24 January indicated human transmission, strongly recommended personal protective equipment for health workers, and said testing for the virus was essential due to its “pandemic potential”.

On 30 January 2020, with 7,818 confirmed cases across 19 countries, the WHO declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), and then a pandemic on 11 March 2020 as Italy, Iran, South Korea, and Japan reported increasing numbers of cases.

On 31 January 2020, Italy had its first confirmed cases, two tourists from China. As of 13 March 2020, the WHO considered Europe the active centre of the pandemic. On 19 March 2020, Italy overtook China as the country with the most reported deaths. By 26 March, the United States had overtaken China and Italy with the highest number of confirmed cases in the world. Research on coronavirus genomes indicates the majority of COVID-19 cases in New York came from European travellers, rather than directly from China or any other Asian country. Retesting of prior samples found a person in France who had the virus on 27 December 2019 and a person in the United States who died from the disease on 6 February 2020.

On 11 June 2020, after 55 days without a locally transmitted case being officially reported, the city of Beijing reported a single COVID-19 case, followed by two more cases on 12 June. As of 15 June 2020, 79 cases were officially confirmed. Most of these patients went to Xinfadi Wholesale Market.

On 29 June 2020, WHO warned that the spread of the virus is still accelerating as countries reopen their economies, although many countries have made progress in slowing down the spread.

On 15 July 2020, one COVID-19 case was officially reported in Dalian in more than three months. The patient did not travel outside the city in the 14 days before developing symptoms, nor did he have contact with people from “areas of attention.”

In October 2020, the WHO stated, at a special meeting of WHO leaders, that one in ten people around the world may have been infected with COVID-19. At the time, that translated to 780 million people being infected, while only 35 million infections had been confirmed.

In early November 2020, Denmark reported on an outbreak of a unique mutated variant being transmitted to humans from minks in its North Jutland Region. All twelve human cases of the mutated variant were identified in September 2020. The WHO released a report saying the variant “had a combination of mutations or changes that have not been previously observed.” In response, Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen ordered for the country – the world’s largest producer of mink fur – to cull its mink population by as many as 17 million.

On 9 November 2020, Pfizer released their trial results for a candidate vaccine, showing that it is 90% effective against the virus. Later that day, Novavax entered an FDA Fast Track application for their vaccine. The 9 November announcement does not mean the vaccine is about to be released. However, virologist and U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director Anthony Fauci indicated that the Pfizer vaccine targets the spike protein used to infect cells by the virus. Some issues left to be answered are how long the vaccine offers protection, and if it offers the same level of protection to all ages. Initial doses will likely go to healthcare workers on the front lines.

On 9 November 2020 the United States surpassed 10 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, making it the country with the most cases worldwide by a large margin.

It was reported on 27 November, that a publication released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicated that the current numbers of viral infection are via confirmed laboratory test only. However, the true number could be about eight times the reported number; the report further indicated that the true number of virus infected cases could be around 100 million in the U.S.

On 14 December 2020, Public Health England reported a new variant had been discovered in the South East of England, predominantly in Kent. The variant, named Variant of Concern 202012/01, showed changes to the spike protein which could make the virus more infectious. As of 13 December, there were 1,108 cases identified. Many countries halted all flights from the UK; France-bound Eurotunnel service was suspended and ferries carrying passengers and accompanied freight were cancelled as the French border closed to people on 20 December.

2021

As of 8 January 2021, more than 88 million cases have been reported worldwide due to COVID-19; more than 1.89 million have died and more than 49 million have recovered.

On 2 January the new variant of COVID-19 (variant of Concern 202012/01) had been identified in 33 countries around the world, including: Pakistan, South Korea, Switzerland, Taiwan, Norway, Italy, Japan, Lebanon, India, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Iceland, China and many more.

National responses

U.S. President Donald Trump signs the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act into law with Alex Azar on 6 March 2020.

A total of 191 countries and territories have had at least one case of COVID-19 so far. Due to the pandemic in Europe, many countries in the Schengen Area have restricted free movement and set up border controls. National reactions have included containment measures such as quarantines and curfews (known as stay-at-home orders, shelter-in-place orders, or lockdowns). The WHO’s recommendation on curfews and lockdowns is that they should be short-term measures to reorganize, regroup, rebalance resources, and protect health workers who are exhausted. To achieve a balance between restrictions and normal life, the long-term responses to the pandemic should consist of strict personal hygiene, effective contact tracing, and isolating when ill.

By 26 March 2020, 1.7 billion people worldwide were under some form of lockdown, which increased to 3.9 billion people by the first week of April—more than half the world’s population.

By late April 2020, around 300 million people were under lockdown in nations of Europe, including but not limited to Italy, Spain, France, and the United Kingdom, while around 200 million people were under lockdown in Latin America. Nearly 300 million people, or about 90 percent of the population, were under some form of lockdown in the United States, around 100 million people in the Philippines, about 59 million people in South Africa, and 1.3 billion people have been under lockdown in India. On 21 May 2020, 100,000 new infections occurred worldwide, the most since the start of the pandemic, while overall 5 million cases were surpassed.

Asia

As of 30 April 2020, cases have been reported in all Asian countries except for Turkmenistan and North Korea, although these countries likely also have cases. Despite being the first area of the world hit by the outbreak, the early wide-scale response of some Asian states, particularly Mongolia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam, has allowed them to fare comparatively well. China is criticized for initially minimizing the severity of the outbreak but the delayed wide-scale response has largely contained the disease since March 2020. As of 9 December 2020, Singapore has the lowest case fatality rate in the world, at 0.51 deaths per 100,000.

The pandemic has had direct side effects, per a report on 28 November, in Japan. According to the report by the country’s National Police Agency, suicides had increased to 2,153 in October. Experts also state that the pandemic has worsened mental health issues due to lockdowns and isolation from family members, among other issues.

China

A temporary hospital constructed in Wuhan in February 2020

As of 14 July 2020, there are 83,545 cases confirmed in China— excluding 114 asymptomatic cases, 62 of which were imported, under medical observation; asymptomatic cases have not been reported prior to 31 March 2020—with 4,634 deaths and 78,509 recoveries, meaning there are only 402 cases. Hubei has the most cases, followed by Xinjiang. By March 2020, COVID-19 infections have largely been put under control in China, with minor outbreaks since. It was reported on 25 November, that some 1 million people in the country of China have been vaccinated according to China’s state council; the vaccines against COVID-19 come from Sinopharm which makes two and one produced by Sinovac.

India

Indian officials conducting temperature checks at the Ratha Yatra Hindu festival on 23 June 2020

The first case of COVID-19 in India was reported on 30 January 2020. India ordered a nationwide lockdown for the entire population starting 24 March 2020, with a phased unlock beginning 1 June 2020. Six cities account for around half of all reported cases in the country—Mumbai, Delhi, Ahmedabad, Chennai, Pune and Kolkata.

As of September 2020, India had the largest number of confirmed cases in Asia; and the second-highest number of confirmed cases in the world, behind the United States, with the number of total confirmed cases breaching the 100,000 mark on 19 May 2020, 1,000,000 on 16 July 2020, and 5,000,000 confirmed cases on 16 September 2020. On 30 August 2020, India surpassed the US record for the most cases in a single day, with more than 78,000 cases, and set a new record on 16 September 2020, with almost 98,000 cases reported that day.

On 10 June 2020, India’s recoveries exceeded active cases for the first time. As of 30 August 2020, India’s case fatality rate is relatively low at 2.3%, against the global 4.7%.

Iran

Disinfection of Tehran Metro trains against coronavirus. Similar measures have also been taken in other countries.

Iran reported its first confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infections on 19 February 2020 in Qom, where, according to the Ministry of Health and Medical Education, two people had died that day. Early measures announced by the government included the cancellation of concerts and other cultural events, sporting events, Friday prayers, and closures of universities, higher education institutions, and schools. Iran allocated 5 trillion rials (equivalent to US$120,000,000) to combat the virus. President Hassan Rouhani said on 26 February 2020 there were no plans to quarantine areas affected by the outbreak, and only individuals would be quarantined. Plans to limit travel between cities were announced in March 2020, although heavy traffic between cities ahead of the Persian New Year Nowruz continued. Shia shrines in Qom remained open to pilgrims until 16 March.

Iran became a centre of the spread of the virus after China during February 2020. More than ten countries had traced their cases back to Iran by 28 February, indicating the outbreak may have been more severe than the 388 cases reported by the Iranian government by that date. The Iranian Parliament was shut down, with 23 of its 290 members reported to have had tested positive for the virus on 3 March 2020. On 15 March 2020, the Iranian government reported a hundred deaths in a single day, the most recorded in the country since the outbreak began. At least twelve sitting or former Iranian politicians and government officials had died from the disease by 17 March 2020. By 23 March 2020, Iran was experiencing fifty new cases every hour and one new death every ten minutes due to coronavirus. According to a WHO official, there may be five times more cases in Iran than what is being reported. It is also suggested that U.S. sanctions on Iran may be affecting the country’s financial ability to respond to the viral outbreak. On 20 April 2020, Iran reopened shopping malls and other shopping areas across the country. After reaching a low in new cases in early May, a new peak was reported on 4 June 2020, raising fear of a second wave. On 18 July 2020, President Rouhani estimated that 25 million Iranians had already become infected, which is considerably higher than the official count. Leaked data suggest that 42,000 people had died with COVID-19 symptoms by 20 July 2020, nearly tripling the 14,405 officially reported by that date.

South Korea

A drive-through test centre at the Gyeongju Public Health Centre

COVID-19 was confirmed to have spread to South Korea on 20 January 2020 from China. The nation’s health agency reported a significant increase in confirmed cases on 20 February, largely attributed to a gathering in Daegu of the Shincheonji Church of Jesus. Shincheonji devotees visiting Daegu from Wuhan were suspected to be the origin of the outbreak. By 22 February, among 9,336 followers of the church, 1,261 or about 13 percent reported symptoms. South Korea declared the highest level of alert on 23 February 2020. On 29 February, more than 3,150 confirmed cases were reported. All South Korean military bases were quarantined after tests showed three soldiers had the virus. Airline schedules were also changed.

South Korea introduced what was considered the largest and best-organised programme in the world to screen the population for the virus, isolate any infected people, and trace and quarantine those who contacted them. Screening methods included mandatory self-reporting of symptoms by new international arrivals through mobile application, drive-through testing for the virus with the results available the next day, and increasing testing capability to allow up to 20,000 people to be tested every day. Despite some early criticisms of President Moon Jae-in’s response to the crisis, South Korea’s programme is considered a success in controlling the outbreak without quarantining entire cities.

On 23 March, it was reported that South Korea had the lowest one-day case total in four weeks. On 29 March it was reported that beginning 1 April all new overseas arrivals will be quarantined for two weeks. Per media reports on 1 April, South Korea has received requests for virus testing assistance from 121 different countries. Persistent local groups of infections in the greater Seoul area continued to be found, which led to Korea’s CDC director saying in June that the country had entered the second wave of infections, although a WHO official disagreed with that assessment.

Europe

Cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 residents in Europe. The numbers are not comparable, as the testing strategy differs among countries and time periods.

As of 13 March 2020, when the number of new cases became greater than those in China, the World Health Organization (WHO) began to consider Europe the active centre of the pandemic. Cases by country across Europe had doubled over periods of typically 3 to 4 days, with some countries (mostly those at earlier stages of detection) showing doubling every 2 days.

As of 17 March, all countries within Europe had a confirmed case of COVID-19, with Montenegro being the last European country to report at least one case. At least one death has been reported in all European countries, apart from the Vatican City.

As of 18 March, more than 250 million people were in lockdown in Europe.

As of 24 May, 68 days since its first recorded case, Montenegro became the first COVID-19-free country in Europe, but this situation lasted only 44 days before a newly imported case was identified there. European countries with the highest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases are Russia, France, Spain, the United Kingdom, and Italy.

On 21 August, it was reported the COVID-19 cases were climbing among younger individuals across Europe. On 21 November, it was reported by the Voice of America that Europe is the worst hit area by the COVID-19 virus, with numbers exceeding 15 million cases

France

Empty streets in Paris, 2020

Although it was originally thought the pandemic reached France on 24 January 2020, when the first COVID-19 case in Europe was confirmed in Bordeaux, it was later discovered that a person near Paris had tested positive for the virus on 27 December 2019 after retesting old samples. A key event in the spread of the disease in the country was the annual assembly of the Christian Open Door Church between 17 and 24 February in Mulhouse, which was attended by about 2,500 people, at least half of whom are believed to have contracted the virus.

On 13 March, Prime Minister Édouard Philippe ordered the closure of all non-essential public places, and on 16 March, French President Emmanuel Macron announced mandatory home confinement, a policy which was extended at least until 11 May. As of 14 September, France has reported more than 402,000 confirmed cases, 30,000 deaths, and 90,000 recoveries, ranking fourth in number of confirmed cases. In April, there were riots in some Paris suburbs. On 18 May, it was reported that schools in France had to close again after reopening, due to COVID-19 case flare-ups.

On 12 November it was reported that France had become the worst hit country by the COVID-19 pandemic, in all of Europe, in the process surpassing Russia. The new total of confirmed cases was more than 1.8 million and counting; additionally it was indicated by the French government that the current national lockdown would remain in place.

Italy

The outbreak was confirmed to have spread to Italy on 31 January, when two Chinese tourists tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in Rome. Cases began to rise sharply, which prompted the Italian government to suspend all flights to and from China and declare a state of emergency. An unassociated cluster of COVID-19 cases was later detected, starting with 16 confirmed cases in Lombardy on 21 February.

Civil Protection volunteers conduct health checks at the Guglielmo Marconi Airport in Bologna on 5 February.

On 22 February, the Council of Ministers announced a new decree-law to contain the outbreak, including quarantining more than 50,000 people from eleven different municipalities in northern Italy. Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte said, “In the outbreak areas, entry and exit will not be provided. Suspension of work activities and sports events has already been ordered in those areas.”

On 4 March, the Italian government ordered the full closure of all schools and universities nationwide as Italy reached a hundred deaths. All major sporting events were to be held behind closed doors until April, but on 9 March all sport was suspended completely for at least one month. On 11 March, Prime Minister Conte ordered stoppage of nearly all commercial activity except supermarkets and pharmacies.

On 6 March, the Italian College of Anaesthesia, Analgesia, Resuscitation and Intensive Care (SIAARTI) published medical ethics recommendations regarding triage protocols. On 19 March, Italy overtook China as the country with the most coronavirus-related deaths in the world after reporting 3,405 fatalities from the pandemic. On 22 March, it was reported that Russia had sent nine military planes with medical equipment to Italy. As of 14 September, there were 287,753 confirmed cases, 35,610 deaths, and 213,634 recoveries in Italy, with the majority of those cases occurring in the Lombardy region. A CNN report indicated that the combination of Italy’s large elderly population and inability to test all who have the virus to date may be contributing to the high fatality rate. On 19 April, it was reported that the country had its lowest deaths at 433 in seven days and some businesses are asking for a loosening of restrictions after six weeks of lockdown. On 13 October 2020, the Italian government again issued restrictive rules to contain a rise in infections.

On 11 November, it was reported that Silvestro Scotti, president of the Italian Federation of General Practitioners indicated that all of Italy should come under restrictions due to the coronavirus. A couple of days prior Filippo Anelli, president of the National Federation of Doctor’s Guilds (FNOMCEO) asked for a complete lockdown of the peninsular nation due to the pandemic. On the 10th, a day before, Italy surpassed 1 million confirmed COVID-19 cases. On 23 November it was reported that the second wave of the virus has caused some hospitals in Italy to stop accepting patients.

Spain

Residents of Valencia, Spain, maintaining social distancing while queueing

The virus was first confirmed to have spread to Spain on 31 January 2020, when a German tourist tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in La Gomera, Canary Islands. Post-hoc genetic analysis has shown that at least 15 strains of the virus had been imported, and community transmission began by mid-February. By 13 March, cases had been confirmed in all 50 provinces of the country.

A lockdown was imposed on 14 March 2020. On 29 March, it was announced that, beginning the following day, all non-essential workers were ordered to remain at home for the next 14 days. By late March, the Community of Madrid has recorded the most cases and deaths in the country. Medical professionals and those who live in retirement homes have experienced especially high infection rates. On 25 March, the official death toll in Spain surpassed that of mainland China. On 2 April, 950 people died of the virus in a 24-hour period—at the time, the most by any country in a single day. On 17 May, the daily death toll announced by the Spanish government fell below 100 for the first time, and 1 June was the first day without deaths by coronavirus. The state of alarm ended on 21 June. However, the number of cases increased again in July in a number of cities including Barcelona, Zaragoza and Madrid, which led to reimposition of some restrictions but no national lockdown.

Studies have suggested that the number of infections and deaths may have been underestimated due to lack of testing and reporting, and many people with only mild or no symptoms were not tested. Reports in May suggested that, based on a sample of more than 63,000 people, the number of infections may be ten times higher than the number of confirmed cases by that date, and Madrid and several provinces of Castilla–La Mancha and Castile and León were the most affected areas with a percentage of infection greater than 10%. There may also be as many as 15,815 more deaths according to the Spanish Ministry of Health monitoring system on daily excess mortality (Sistema de Monitorización de la Mortalidad Diaria – MoMo). On 6 July 2020, the results of a Government of Spain nationwide seroprevalence study showed that about two million people, or 5.2% of the population, could have been infected during the pandemic. Spain was the second country in Europe (behind Russia) to record half a million cases. On 21 October, Spain passed 1 million COVID-19 cases, with 1,005,295 infections and 34,366 deaths reported as of 21 October a third of which occurred in Madrid.

Sweden

Sweden differed from most other European countries in that it mostly remained open. Per the Swedish Constitution, the Public Health Agency of Sweden has autonomy which prevents political interference and the agency’s policy favoured forgoing a lockdown. The Swedish strategy focused on measures that could be put in place over a longer period of time, based on the assumption that the virus would start spreading again after a shorter lockdown. The New York Times said that, as of May 2020, the outbreak had been far deadlier there but the economic impact had been reduced as Swedes have continued to go to work, restaurants, and shopping. On 19 May, it was reported that the country had in the week of 12–19 May the highest per capita deaths in Europe, 6.25 deaths per million per day. In the end of June, Sweden no longer had excess mortality.

United Kingdom

The “Wee Annie” statue in Gourock, Scotland, was given a face mask during the pandemic.

Devolution in the United Kingdom meant that each of the four countries of the UK had its own different response to COVID-19, and the UK government, on behalf of England, moved quicker to lift restrictions. The UK government started enforcing social distancing and quarantine measures on 18 March 2020 and was criticised for a perceived lack of intensity in its response to concerns faced by the public. On 16 March, Prime Minister Boris Johnson advised against non-essential travel and social contact, suggesting people work from home and avoid venues such as pubs, restaurants, and theatres. On 20 March, the government ordered all leisure establishments to close as soon as possible, and promised to prevent unemployment. On 23 March, Johnson banned gatherings of multiple people and restricting non-essential travel and outdoor activity. Unlike previous measures, these restrictions were enforceable by police through fines and dispersal of gatherings. Most non-essential businesses were ordered to close.

On 24 April it was reported that a promising vaccine trial had begun in England; the government pledged more than £50 million towards research. A number of temporary critical care hospitals were built. The first operating was the 4000-bed NHS Nightingale Hospital London, constructed for over nine days. On 4 May, it was announced that it would be placed on standby and remaining patients transferred to other facilities; 51 patients had been treated in the first three weeks.

On 16 April it was reported that the UK would have first access to the Oxford vaccine, due to a prior contract; should the trial be successful, some 30 million doses in the UK would be available.

On 2 December the UK became the first Western country to approve the Pfizer vaccine against the COVID-19 virus; 800,000 doses will be immediately available for use It was reported on 5 December that the United Kingdom would begin vaccination against the virus on 8 December, less than a week after having been approved. On 9 December, MHRA stated that any individual with a significant allergic reaction to a vaccine, such as an anaphylactoid reaction, should not take the Pfizer vaccine for COVID-19 protection.

North America

The first cases in North America were reported in the United States in January 2020. Cases were reported in all North American countries after Saint Kitts and Nevis confirmed a case on 25 March, and in all North American territories after Bonaire confirmed a case on 16 April.

Canada reported 117,658 cases and 3,842 deaths on 30 July, while Mexico reported 416,179 cases and 46,000 deaths. The most cases by state is Texas with about 17,279 deaths and over 849,000 confirmed cases.

United States

The hospital ship USNS Comfort arrives in Manhattan on 30 March 2020

More than 21,500,000 confirmed cases have been reported in the United States since January 2020, resulting in more than 365,000 deaths, the most of any country and the fourteenth-highest on a per capita basis. The U.S. has nearly a quarter of the world’s cases and a fifth of all deaths. COVID-19 became the third leading cause of death in the U.S. in 2020, behind heart disease and cancer.

The first American case was reported on January 20, and president Donald Trump declared the U.S. outbreak a public health emergency on January 31. Restrictions were placed on flights arriving from China, but the initial U.S. response to the pandemic was otherwise slow, in terms of preparing the healthcare system, stopping other travel, and testing. Meanwhile, Trump downplayed the threat posed by the virus and claimed the outbreak was under control.

The first known American deaths occurred in February. On March 6, Trump signed the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, which provided $8.3 billion in emergency funding for federal agencies to respond to the outbreak. On March 13, President Trump declared a national emergency. In mid-March, the Trump administration started to purchase large quantities of medical equipment, and in late March, it invoked the Defense Production Act to direct industries to produce medical equipment. By April 17, the federal government approved disaster declarations for all states and territories. By mid-April, cases had been confirmed in all fifty U.S. states, and by November in all inhabited U.S. territories. A second rise in infections began in June 2020, following relaxed restrictions in several states.

South America

Argentina was among the Latin American countries that earned the best grades for their response to the pandemic.

The pandemic was confirmed to have reached South America on 26 February 2020 when Brazil confirmed a case in São Paulo. By 3 April, all countries and territories in South America had recorded at least one case.

On 13 May, it was reported that Latin America and the Caribbean had reported over 400,000 cases of infection with 23,091 deaths. On 22 May, citing especially the rapid increase of infections in Brazil, the WHO declared South America the epicentre of the pandemic.

As of 20 September, South America has about 7.5 million confirmed cases and 238,000 deaths. Due to a dearth of testing and medical facilities, it is believed that the outbreak is far larger than the official numbers show.

Brazil

Doctors check on a patient on a ventilator at InCor in São Paulo

On 20 May it was reported that Brazil had a record 1,179 deaths in a single day, for a total of almost 18,000 fatalities. With a total number of almost 272,000 cases, Brazil became the country with the third-highest number of cases, following Russia and the United States. On 25 May, Brazil exceeded the number of reported cases in Russia when they reported that 11,687 new cases had been confirmed over the previous 24 hours, bringing the total number to over 374,800, with more than 23,400 deaths. President Jair Bolsonaro has created a great deal of controversy referring to the virus as a “little flu” and frequently speaking out against preventive measures such as lockdowns and quarantines. His attitude towards the outbreak has so closely matched that of President Trump he has been called the “Trump of the Tropics”. Bolsonaro later tested positive for the virus.

In June 2020, the government of Brazil attempted to conceal the actual figures of the COVID-19 active cases and deaths, as it stopped publishing the total number of infections and deaths. On 5 June, Brazil’s health ministry took down the official website reflecting the total numbers of infections and deaths. The website was live on 6 June, with only the number of infections of the previous 24 hours. The last official numbers reported about 615,000 infections and over 34,000 deaths. On 15 June, it was reported that the worldwide cases had jumped from seven to eight million in one week, citing Latin America, specifically Brazil as one of the countries where cases are surging, in this case, towards 1 million cases. Brazil briefly paused Phase III trials for the CoronavacCOVID-19 vaccine on 10 November after the suicide of a volunteer before resuming on 11 November.

Africa

U.S. Air Force personnel unload a C-17 aircraft carrying approximately 1,800 kg (4,000 lb) of medical supplies in Niamey, Niger.

Oceania

Antarctica

International responses

Travel restrictions

As a result of the pandemic, many countries and regions imposed quarantines, entry bans, or other restrictions, either for citizens, recent travellers to affected areas, or for all travellers. Together with a decreased willingness to travel, this had a negative economic and social impact on the travel sector. Concerns have been raised over the effectiveness of travel restrictions to contain the spread of COVID-19. A study in Science found that travel restrictions had only modestly affected the initial spread of COVID-19, unless combined with infection prevention and control measures to considerably reduce transmissions. Researchers concluded that “travel restrictions are most useful in the early and late phase of an epidemic” and “restrictions of travel from Wuhan unfortunately came too late”.

The European Union rejected the idea of suspending the Schengen free travel zone and introducing border controls with Italy, a decision which has been criticised by some European politicians.

Evacuation of foreign citizens

Ukraine evacuates Ukrainian and foreign citizens from Wuhan, China.

Owing to the effective lockdown of Wuhan and Hubei, several countries evacuated their citizens and diplomatic staff from the area, primarily through chartered flights of the home nation, with Chinese authorities providing clearance. Canada, the United States, Japan, India, Sri Lanka, Australia, France, Argentina, Germany, and Thailand were among the first to plan the evacuation of their citizens. Brazil and New Zealand also evacuated their own nationals and some other people. On 14 March, South Africa repatriated 112 South Africans who tested negative for the virus from Wuhan, while four who showed symptoms were left behind to mitigate risk. Pakistan said it would not evacuate citizens from China.

On 15 February, the U.S. announced it would evacuate Americans aboard the cruise ship Diamond Princess, and on 21 February, Canada evacuated 129 Canadian passengers from the ship. In early March, the Indian government began evacuating its citizens from Iran. On 20 March, the United States began to partially withdraw its troops from Iraq due to the pandemic.

United Nations response measures

The United Nations response to the pandemic has been led by its Secretary-General and can be divided into formal resolutions at the General Assembly and the Security Council (UNSC), and operations via its specialized agencies.

In June 2020, the Secretary-General launched its ‘UN Comprehensive Response to COVID-19’. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNSC) has been criticized for a slow coordinated response, especially regarding the UN’s global ceasefire, which aims to open up humanitarian access to the world’s most vulnerable in conflict zones.

WHO response measures

The WHO is a leading organisation involved in the global coordination for mitigating the pandemic.

The WHO has spearheaded several initiatives like the COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund to raise money for the pandemic response, the UN COVID-19 Supply Chain Task Force, and the solidarity trial for investigating potential treatment options for the disease.

In responding to the outbreak, the WHO has had to deal with political conflicts between member states, in particular between the United States and China. On May 19, the WHO agreed to an independent investigation into its handling of the pandemic. On August 27, the WHO announced the setting up of an independent expert Review Committee to examine aspects of the international treaty that governs preparedness and response to health emergencies.

Protests against governmental measures

In several countries, protests have risen against governmental restrictive responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as lockdowns.

Impact

Economics

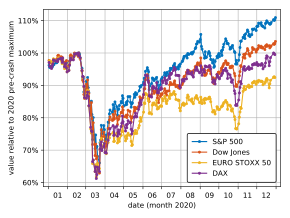

A stock index chart shows the 2020 stock market crash

The outbreak is a major destabilising threat to the global economy. Agathe Demarais of the Economist Intelligence Unit has forecast that markets will remain volatile until a clearer image emerges on potential outcomes. One estimate from an expert at Washington University in St. Louis gave a $300+ billion impact on the world’s supply chain that could last up to two years. Global stock markets fell on 24 February due to a significant rise in the number of COVID-19 cases outside China. On 27 February, due to mounting worries about the coronavirus outbreak, U.S. stock indexes posted their sharpest falls since 2008, with the Dow falling 1,191 points (the largest one-day drop since the financial crisis of 2007–08) and all three major indexes ending the week down more than 10 percent. On 28 February, Scope Ratings GmbH affirmed China’s sovereign credit rating but maintained a Negative Outlook. Stocks plunged again due to coronavirus fears, the largest fall being on 16 March.

Lloyd’s of London has estimated that the global insurance industry will absorb losses of US$204 billion, exceeding the losses from the 2017 Atlantic Hurricane season and 11 September attacks, suggesting the COVID-19 pandemic will likely go down in history as the costliest disaster ever in human history.

A highway sign in Toronto discouraging non-essential travel during the pandemic lockdown in March 2020

Tourism is one of the worst affected sectors due to travel bans, closing of public places including travel attractions, and advice of governments against travel. Numerous airlines have cancelled flights due to lower demand, and British regional airline Flybe collapsed. The cruise line industry was hard hit, and several train stations and ferry ports have also been closed. International mail between some countries stopped or was delayed due to reduced transportation between them or suspension of domestic service.

The retail sector has been impacted globally, with reductions in store hours or temporary closures. Visits to retailers in Europe and Latin America declined by 40 percent. North America and Middle East retailers saw a 50–60 percent drop. This also resulted in a 33–43 percent drop in foot traffic to shopping centres in March compared to February. Shopping mall operators around the world imposed additional measures, such as increased sanitation, installation of thermal scanners to check the temperature of shoppers, and cancellation of events.

Those who can, put something in; those who can’t, help yourself. Bologna, April 2020.

Hundreds of millions of jobs could be lost globally. More than 40 million Americans lost their jobs and filed unemployment insurance claims. The economic impact and mass unemployment caused by the pandemic has raised fears of a mass eviction crisis, with an analysis by the Aspen Institute indicating between 30 and 40 million Americans are at risk for eviction by the end of 2020. According to a report by the Yelp, about 60% of U.S. businesses that have closed since the start of the pandemic will stay shut permanently.

According to a United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America estimate, the pandemic-induced recession could leave 14–22 million more people in extreme poverty in Latin America than would have been in that situation without the pandemic. According to the World Bank, up to 100 million more people globally could fall into extreme poverty due to the shutdowns. The International Labour Organization (ILO) informed that the income generated in first nine months of 2020 from work across the world dropped by 10.7 per cent, or $3.5 trillion, amidst the coronavirus outbreak.

Supply shortages

Coronavirus fears have led to panic buying of essentials across the world, including toilet paper, dried and instant noodles, bread, rice, vegetables, disinfectant, and rubbing alcohol.

The outbreak has been blamed for several instances of supply shortages, stemming from globally increased usage of equipment to fight outbreaks, panic buying (which in several places led to shelves being cleared of grocery essentials such as food, toilet paper, and bottled water), and disruption to the factory and logistic operations. The spread of panic buying has been found to stem from perceived threat, perceived scarcity, fear of the unknown, coping behaviour and social psychological factors (e.g. social influence and trust). The technology industry, in particular, has warned of delays to shipments of electronic goods. According to the WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom, demand for personal protection equipment has risen a hundredfold, leading to prices up to twenty times the normal price and also delays in the supply of medical items of four to six months. It has also caused a shortage of personal protective equipment worldwide, with the WHO warning that this will endanger health workers.

The impact of the coronavirus outbreak was worldwide. The virus created a shortage of precursors (raw material) used in the manufacturing of fentanyl and methamphetamine. The Yuancheng Group, headquartered in Wuhan, is one of the leading suppliers. Price increases and shortages in these illegal drugs have been noticed on the street of the UK. U.S. law enforcement also told the New York Post Mexican drug cartels were having difficulty in obtaining precursors.

The pandemic has disrupted global food supplies and threatens to trigger a new food crisis. David Beasley, head of the World Food Programme (WFP), said “we could be facing multiple famines of biblical proportions within a short few months.” Senior officials at the United Nations estimated in April 2020 that an additional 130 million people could starve, for a total of 265 million by the end of 2020.

Oil and other energy markets

In early February 2020, Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) “scrambled” after a steep decline in oil prices due to lower demand from China. On Monday, 20 April, the price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) went negative and fell to a record low (minus $37.63 a barrel) due to traders’ offloading holdings so as not to take delivery and incur storage costs. June prices were down but in the positive range, with a barrel of West Texas trading above $20.

Culture

Closed entrance to the Shah Abdol-Azim Shrine in Ray, Iran

The performing arts and cultural heritage sectors have been profoundly affected by the pandemic, impacting organisations’ operations as well as individuals—both employed and independent—globally. Arts and culture sector organisations attempted to uphold their (often publicly funded) mission to provide access to cultural heritage to the community, maintain the safety of their employees and the public, and support artists where possible. By March 2020, across the world and to varying degrees, museums, libraries, performance venues, and other cultural institutions had been indefinitely closed with their exhibitions, events and performances cancelled or postponed. In response there were intensive efforts to provide alternative services through digital platforms.

An American Catholic military chaplain prepares for a live-streamed Mass in an empty chapel at Offutt Air Force Base in March 2020.