Robin McLaurin Williams July 21, 1951 – August 11, 2014 was an American actor and comedian. Known for his improvisational skills and a wide variety of voices, he is often regarded as one of the best comedians of all time. Williams began performing stand-up comedy in San Francisco and Los Angeles during the mid-1970s, and rose to fame playing the alien Mork in the sitcom Mork & Mindy (1978–1982).

After his first starring film role in Popeye (1980), Williams starred in several critically and commercially successful films including The World According to Garp (1982), Moscow on the Hudson (1984), Good Morning, Vietnam (1987), Dead Poets Society (1989), Awakenings (1990), The Fisher King (1991), Patch Adams (1998), One Hour Photo (2002), and World’s Greatest Dad (2009). He also starred in box office successes such as Hook (1991), Aladdin (1992), Mrs. Doubtfire (1993), Jumanji (1995), The Birdcage (1996), Good Will Hunting (1997), and the Night at the Museum trilogy (2006–2014). He was nominated for four Academy Awards, winning Best Supporting Actor for Good Will Hunting. He also received two Primetime Emmy Awards, six Golden Globe Awards, two Screen Actors Guild Awards, and five Grammy Awards.

In August 2014, at age 63, Williams committed suicide at his home in Paradise Cay, California. His widow, Susan Schneider Williams—as well as medical experts and the autopsy—attributed his suicide to his struggle with Lewy body disease.

Early life

Robin McLaurin Williams was born at St. Luke’s Hospital in Chicago, Illinois, on July 21, 1951. His father, Robert Fitzgerald Williams, was a senior executive in Ford’s Lincoln-Mercury Division. His mother, Laurie McLaurin, was a former model from Jackson, Mississippi, whose great-grandfather was Mississippi senator and governor Anselm J. McLaurin, a Democrat. Williams had two elder half-brothers: paternal half-brother Robert (also known as Todd) and maternal half-brother McLaurin. He had English, French, German, Irish, Scottish, and Welsh ancestry. While his mother was a practitioner of Christian Science, Williams was raised in his father’s Episcopal faith. During a television interview on Inside the Actors Studio in 2001, Williams credited his mother as an important early influence on his humor, and he tried to make her laugh to gain attention.

Williams attended public elementary school in Lake Forest at Gorton Elementary School and middle school at Deer Path Junior High School. He described himself as a quiet child who did not overcome his shyness until he became involved with his high school drama department. His friends recall him as very funny. In late 1963, when Williams was 12, his father was transferred to Detroit. The family lived in a 40-room farmhouse on 20 acres in suburban Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, where he was a student at the private Detroit Country Day School. He excelled in school, where he was on the school’s wrestling team and was elected class president.

As both his parents worked, Williams was partially raised by the family’s maid, who was his main companion. When he was 16, his father took early retirement and the family moved to Tiburon, California. Following their move, Williams attended Redwood High School in nearby Larkspur. At the time of his graduation in 1969, he was voted “Most Likely Not to Succeed” and “Funniest” by his classmates. After high school graduation, Williams enrolled at Claremont Men’s College in Claremont, California, to study political science; he dropped out to pursue acting. Williams studied theatre for three years at the College of Marin, a community college in Kentfield, California. According to College of Marin’s drama professor James Dunn, the depth of the young actor’s talent became evident when he was cast in the musical Oliver! as Fagin. Williams often improvised during his time in the drama program, leaving cast members in hysterics. Dunn called his wife after one late rehearsal to tell her Williams “was going to be something special”.

In 1973, Williams attained a full scholarship to the Juilliard School (Group 6, 1973–1976) in New York City. He was one of 20 students accepted into the freshman class, and he and Christopher Reeve were the only two accepted by John Houseman into the Advanced Program at the school that year. William Hurt and Mandy Patinkin were also classmates. According to biographer Jean Dorsinville, Franklyn Seales and Williams were roommates at Juilliard. Reeve remembered his first impression of Williams when they were new students at Juilliard: “He wore tie-dyed shirts with tracksuit bottoms and talked a mile a minute. I’d never seen so much energy contained in one person. He was like an untied balloon that had been inflated and immediately released. I watched in awe as he virtually caromed off the walls of the classrooms and hallways. To say that he was ‘on’ would be a major understatement.”

Williams and Reeve had a class in dialects taught by Edith Skinner, who Reeve said was one of the world’s leading voice and speech teachers; according to Reeve, Skinner was bewildered by Williams and his ability to instantly perform in many different accents. Their primary acting teacher was Michael Kahn, who was “equally baffled by this human dynamo”. Williams already had a reputation for being funny, but Kahn criticized his antics as simple stand-up comedy. In a later production, Williams silenced his critics with his well-received performance as an old man in Tennessee Williams’s Night of the Iguana. Reeve wrote, “He simply was the old man. I was astonished by his work and very grateful that fate had thrown us together.” The two remained close friends until Reeve’s death in 2004. Reeve had famously struggled for years with being quadriplegic after a horse-riding accident.:16 Their friendship was like “brothers from another mother”, according to Williams’s son Zak. Williams paid many of Reeve’s medical bills and gave financial support to his family.

During the summers of 1974, 1975, and 1976, Williams worked as a busboy at The Trident in Sausalito, California. He left Juilliard during his junior year in 1976 at the suggestion of Houseman, who said there was nothing more Juilliard could teach him. Gerald Freedman, another of his teachers at Juilliard, said Williams was a “genius” and that the school’s conservative and classical style of training did not suit him; no one was surprised that he left.

Career

Stand-up comedy

Williams at a USO show on December 20, 2007

Williams began performing stand-up comedy in the San Francisco Bay Area in 1976. He gave his first performance at the Holy City Zoo, a comedy club in San Francisco, where he worked his way up from tending bar. In the 1960s, San Francisco was a center for a rock music renaissance, hippies, drugs, and a sexual revolution, and in the late 1970s, Williams helped lead its “comedy renaissance”, writes critic Gerald Nachman.:6 Williams says he found out about “drugs and happiness” during that period, adding that he saw “the best brains of my time turned to mud”.

Williams moved to Los Angeles and continued performing stand-up at clubs including The Comedy Store. There, in 1977, he was seen by TV producer George Schlatter, who asked him to appear on a revival of his show Laugh-In. The show aired in late 1977 and was his debut TV appearance. That year, Williams also performed a show at the L.A. Improv for Home Box Office. While the Laugh-In revival failed, it led Williams into his television career; he continued performing stand-up at comedy clubs such as the Roxy to help keep his improvisational skills sharp. In England, Williams notably performed at The Fighting Cocks.

With his success on Mork & Mindy, Williams began to reach a wider audience with his stand-up comedy, starting in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, including three HBO comedy specials: Off The Wall (1978), An Evening with Robin Williams (1983), and A Night at the Met (1986). Williams won a Grammy Award for Best Comedy Album for the recording of his 1979 live show at the Copacabana in New York, Reality … What a Concept.

David Letterman, who knew Williams for nearly 40 years, recalls seeing him first perform as a new comedian at The Comedy Store in Hollywood, where Letterman and other comedians had already been doing stand-up. “He came in like a hurricane”, said Letterman, who said he then thought to himself, “Holy crap, there goes my chance in show business.”

Williams at Aviano Air Base (Italy) on December 22, 2007

Williams said that partly due to the stress of performing stand-up, he started using drugs and alcohol early in his career. He further said that he neither drank nor took drugs while on stage, but occasionally performed when hung over from the previous day. During the period he was using cocaine, he said it made him paranoid when performing on stage.

Williams once described the life of stand-up comedians:

“It’s a brutal field, man. They burn out. It takes its toll. Plus, the lifestyle—partying, drinking, drugs. If you’re on the road, it’s even more brutal. You gotta come back down to mellow your ass out, and then performing takes you back up. They flame out because it comes and goes. Suddenly they’re hot, and then somebody else is hot. Sometimes they get very bitter. Sometimes they just give up. Sometimes they have a revival thing and they come back again. Sometimes they snap. The pressure kicks in. You become obsessed and then you lose that focus that you need.”:34–35

Some, such as the critic Vincent Canby, were concerned that his monologues were so intense it seemed as though at any minute his “creative process could reverse into a complete meltdown”. His biographer, Emily Herbert, described his “intense, utterly manic style of stand-up defies analysis … beyond energetic, beyond frenetic … dangerous … because of what it said about the creator’s own mental state”.

Williams felt secure that he would not run out of ideas, as the constant change in world events would keep him supplied. He also explained that he often used free association of ideas while improvising in order to keep the audience interested. The competitive atmosphere caused problems; for example, some comedians accused him of stealing their jokes, which Williams strongly denied. David Brenner claims that he confronted Williams’s agent and threatened bodily harm if he heard Williams utter another one of his jokes. Whoopi Goldberg defended him, asserting that it is difficult for comedians not to reuse another comedian’s material, and that it is done “all the time”. He later avoided going to performances of other comedians to deter similar accusations.

During a Playboy interview in 1992, Williams was asked whether he ever feared losing his balance between his work and his life. He replied, “There’s that fear—if I felt like I was becoming not just dull but a rock, that I still couldn’t speak, fire off or talk about things, if I’d start to worry or got too afraid to say something. … If I stop trying, I get afraid.” While he attributed the recent suicide of novelist Jerzy Kosiński to his fear of losing his creativity and sharpness, Williams felt he could overcome those risks. For that, he credited his father for strengthening his self-confidence, telling him to never be afraid of talking about subjects which were important to him.

Williams’s stand-up work was a consistent thread through his career, as seen by the success of his one-man show (and subsequent DVD) Robin Williams: Live on Broadway (2002). In 2004, he was voted 13th on Comedy Central’s list “100 Greatest Stand-ups of All Time”. After a six-year hiatus, in August 2008, Williams announced a new 26-city tour, Weapons of Self-Destruction. The tour began at the end of September 2009 and concluded in New York on December 3, and was the subject of an HBO special on December 8, 2009.

Television

Mork & Mindy

After the Laugh-In revival and appearing in the cast of The Richard Pryor Show on NBC, Williams was cast by Garry Marshall as the alien Mork in a 1978 episode of the TV series Happy Days, “My Favorite Orkan”. Sought after as a last-minute cast replacement for a departing actor, Williams impressed the producer with his quirky sense of humor when he sat on his head when asked to take a seat for the audition. As Mork, Williams improvised much of his dialogue and physical comedy, speaking in a high, nasal voice, and he made the most of the script. The cast and crew, as well as TV network executives were deeply impressed with his performance.

Mork’s appearance proved so popular with viewers that it led to the spin-off television sitcom Mork & Mindy, which co-starred Pam Dawber, and ran from 1978 to 1982; the show was written to accommodate his extreme improvisations in dialog and behavior. Although he portrayed the same character as in Happy Days, the series was set in the present in Boulder, Colorado, instead of the late 1950s in Milwaukee. Mork & Mindy at its peak had a weekly audience of sixty million and was credited with turning Williams into a “superstar”. According to critic James Poniewozik, the series was especially popular among young people as Williams became a “man and a child, buoyant, rubber-faced, an endless gusher of invention”.

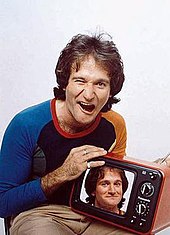

Robin Williams (1979)

Mork became popular, featured on posters, coloring books, lunch-boxes, and other merchandise. Mork & Mindy was such a success in its first season that Williams appeared on the March 12, 1979, cover of Time magazine. The cover photo, taken by Michael Dressler in 1979, is said to have ” his different sides: the funnyman mugging for the camera, and a sweet, more thoughtful pose that appears on a small TV he holds in his hands” according to Mary Forgione of the Los Angeles Times. This photo was installed in the National Portrait Gallery in the Smithsonian Institution shortly after his death to allow visitors to pay their respects. Williams also appeared on the cover of the August 23, 1979, issue of Rolling Stone, photographed by Richard Avedon.

Later appearances

Starting in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, Williams began to reach a wider audience with his stand-up comedy, including three HBO comedy specials, Off the Wall (1978), An Evening with Robin Williams (1983), and A Night at the Met (1986). In 1986, Williams co-hosted the 58th Academy Awards. Williams was also a regular guest on various talk shows, including The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson and Late Night with David Letterman, on which he appeared 50 times.

Williams and Billy Crystal were in an unscripted cameo at the beginning of an episode of the third season of Friends. His many TV appearances included an episode of Whose Line Is It Anyway?, and he starred in an episode of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit. In 2006, Williams was the Surprise Guest at the Nickelodeon Kids’ Choice Awards, and appeared on an episode of Extreme Makeover: Home Edition that aired on January 30.

In 2010, he appeared in a sketch with Robert De Niro on Saturday Night Live, and in 2012, guest-starred as himself in two FX series, Louie and Wilfred. In May 2013, CBS started a new series, The Crazy Ones, starring Williams, but the show was canceled after one season.

Film

The first film role credited to Robin Williams is a small part in the 1977 low-budget comedy Can I Do It… ‘Til I Need Glasses?. His first starring performance, however, is as the title character in Popeye (1980), in which Williams showcased the acting skills previously demonstrated in his television work; accordingly, the film’s commercial disappointment was not blamed on his performance. He went on to star as the leading character in The World According to Garp (1982), which Williams considered “may have lacked a certain madness onscreen, but it had a great core”. He continued with other smaller roles in less successful films, such as The Survivors (1983) and Club Paradise (1986), though he said these roles did not help advance his film career.

His first major break came from his starring role in director Barry Levinson’s Good Morning, Vietnam (1987), which earned Williams a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor. The film is set in 1965 during the Vietnam War, with Williams playing the role of Adrian Cronauer, a radio shock jock who keeps the troops entertained with comedy and sarcasm. Williams was allowed to play the role without a script, improvising most of his lines. Over the microphone, he created voice impressions of people, including Walter Cronkite, Gomer Pyle, Elvis Presley, Mr. Ed, and Richard Nixon. “We just let the cameras roll”, said producer Mark Johnson, and Williams “managed to create something new for every single take”.

Dramatic roles

Williams and Yola Czaderska-Hayek at the 62nd Academy Awards in 1990

Many of his subsequent roles were in comedies tinged with pathos. Looking over most of his filmography, one writer was “struck by the breadth” and radical diversity of most roles Williams portrayed. In 1989, Williams played a private-school English teacher in Dead Poets Society, which included a final, emotional scene that some critics said “inspired a generation” and became a part of pop culture. Similarly, his performance as a therapist in Good Will Hunting (1997) deeply affected even some real therapists. In Awakenings (1990), Williams plays a doctor modeled after Oliver Sacks, who wrote the book on which the film is based. Sacks later said the way the actor’s mind worked was a “form of genius”. In 1991, he played an adult Peter Pan in the film Hook, although he had said he would have to lose 25 pounds for the role. Terry Gilliam, who directed Williams in two of his films, The Fisher King (1991) and The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988), said in 1992 that Williams had the ability to “go from manic to mad to tender and vulnerable … the most unique mind on the planet. There’s nobody like him out there.”

Other performances Williams had in dramatic films include Moscow on the Hudson (1984), What Dreams May Come (1998), and Bicentennial Man (1999). In Insomnia (2002), Williams portrayed a murderer on the run from a sleep-deprived Los Angeles police detective (played by Al Pacino) in rural Alaska. Also in 2002, in the psychological thriller One Hour Photo, Williams portrayed an emotionally disturbed photo development technician who becomes obsessed with a family for whom he has developed pictures for a long time. The last film of Williams’s released during his lifetime was The Angriest Man in Brooklyn, in which Williams played Henry Altmann, an angry, bitter man who reassesses his life and works to redeem himself after being told he has a terminal illness.

His roles in comedy and dramatic films garnered Williams several accolades, including an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his role in Good Will Hunting; as well as two previous Academy Award nominations, for Dead Poets Society, and as a troubled homeless man in The Fisher King, respectively.

Among the actors who helped him during his acting career, he credited Robert De Niro, from whom he learned the power of silence and economy of dialogue when acting. From Dustin Hoffman, with whom he co-starred in Hook, he learned to take on totally different character types, and to transform his characters by extreme preparation. Mike Medavoy, producer of Hook, told its director, Steven Spielberg, that he intentionally teamed up Hoffman and Williams for the film because he knew they wanted to work together, and that Williams welcomed the opportunity of working with Spielberg. Williams benefited from working with Woody Allen, who directed him and Billy Crystal in Deconstructing Harry (1997), as Allen had knowledge of the fact that Crystal and Williams had often performed together on stage.

Voice roles

Williams in Washington, D.C. in 1996

Williams voiced characters in several animated films. His voice role as the Genie in the animated musical Aladdin (1992) was written for him. The film’s directors said they had taken a risk by writing the role. At first, Williams refused the role since it was a Disney movie, and he did not want the studio profiting by selling merchandise based on the movie. He accepted the role with certain conditions: “I’m doing it basically because I want to be part of this animation tradition. I want something for my children. One deal is, I just don’t want to sell anything—as in Burger King, as in toys, as in stuff.” Williams improvised much of his dialogue, recording approximately 30 hours of tape, and impersonated dozens of celebrities, including Ed Sullivan, Jack Nicholson, Robert De Niro, Groucho Marx, Rodney Dangerfield, William F. Buckley Jr., Peter Lorre, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Arsenio Hall. His role in Aladdin became one of his most recognized and best-loved, and the film was the highest-grossing of 1992; it won numerous awards, including a Special Golden Globe Award for Vocal Work in a Motion Picture for Williams. His performance led the way for other animated films to incorporate actors with more star power. He was named a Disney Legend in 2009.

Williams continued to provide voices in other animated films, including FernGully: The Last Rainforest (1992), Robots (2005), Happy Feet (2006), and an uncredited vocal performance in Everyone’s Hero (2006). He also voiced the holographic character Dr. Know in the live-action film A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001). He was the voice of The Timekeeper, a former attraction at the Walt Disney World Resort about a time-traveling robot who encounters Jules Verne and brings him to the future.

Later films

Years after the films, Janet Hirshenson revealed in an interview that Williams had expressed interest in portraying Rubeus Hagrid in the Harry Potter film series, but was rejected by director Chris Columbus due to the “British-only edict”. In 2006, he starred in five movies, including Man of the Year and The Night Listener, the latter being a thriller about a radio show host who realizes that a child with whom he has developed a friendship may or may not exist. After his death in 2014, four films starring Williams were released: Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb, A Merry Friggin’ Christmas, Boulevard, and Absolutely Anything.

Stage work

Williams at the USO World Gala in Washington, D.C., on October 1, 2008

Williams appeared opposite Steve Martin at Lincoln Center in an off-Broadway production of Waiting for Godot in 1988. He headlined his own one-man show, Robin Williams: Live on Broadway, which played at the Broadway theatre in July 2002. He made his Broadway acting debut in Rajiv Joseph’s Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo, which opened at the Richard Rodgers Theatre on March 31, 2011.

Internet

Williams hosted a talk show for Audible, which premiered in April 2000 and was available exclusively from Audible’s website.

Work

Theatre

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | Waiting for Godot | Estragon | Lincoln Center Theatre, New York |

| 2011 | Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo | Tiger | Richard Rodgers Theatre, Broadway |

Discography

- Reality … What a Concept, (Casablanca, 1979)

- Throbbing Python of Love, (Casablanca, 1983)

- A Night at the Met, (Columbia, 1986)

- Live 2002, (Columbia, 2002)

- Weapons of Self Destruction, (Sony Music, 2009)

Personal life

Marriages and children