Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 1859 – 4 June 1941), anglicised as William II, was the last German Emperor (Kaiser) and King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until his abdication on 9 November 1918. Despite strengthening Germany’s position as a great power by building a blue-water navy and promoting scientific innovation, his tactless public statements greatly antagonized the international community and his foreign policy was seen by many as one of the causes for the outbreak of World War I. When the German war effort collapsed after a series of crushing defeats on the Western Front in 1918, he was forced to abdicate, thereby bringing an end to the three-hundred-year rule of the House of Hohenzollern.

As the eldest grandchild of Queen Victoria, Wilhelm’s first cousins included King George V of the United Kingdom and many princesses who, along with Wilhelm’s sister Sophia, became European consorts. For most of his life before becoming emperor, he was second in line to succeed his grandfather Wilhelm I on the German and Prussian thrones after his father, Frederick. His grandfather and father both died in 1888, the Year of the Three Emperors, and Wilhelm ascended the throne as German emperor and king of Prussia on 15 June 1888. On 20 March 1890, he dismissed the German Empire’s powerful longtime chancellor, Otto von Bismarck.

After Bismarck’s departure, Wilhelm II assumed direct control over his nation’s policies and embarked on a bellicose “New Course” to cement its status as a respected world power. Subsequently, over the course of his reign, Germany acquired territories in China and the Pacific (such as Kiautschou Bay, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the Caroline Islands) and became Europe’s largest manufacturer. However, he frequently undermined such progress by making threatening statements towards other countries and voicing xenophobic views without consulting his ministers. Likewise, his regime did much to alienate itself from the world’s other powerful nations by initiating a massive naval build-up, challenging French control of Morocco, and building a railway through Baghdad that threatened Britain’s dominion in the Persian Gulf. Thus, by the second decade of the 20th century, Germany could rely only on significantly weaker nations such as Austria-Hungary and the declining Ottoman Empire as its allies.

Wilhelm II’s turbulent reign culminated in Germany’s guarantee of military support to Austria-Hungary during the crisis of July 1914, one of the direct underlying causes for the World War I. A lax wartime leader, he left virtually all decision-making regarding strategy and organisation of the war effort to the Imperial German Army’s Great General Staff. By 29 August 1916, this broad delegation of power resulted in a de facto military dictatorship that dominated national policy for the rest of the conflict. Despite emerging victorious over Russia and achieving significant gains in Western Europe, Germany was forced to relinquish all its conquests after its forces’ decisive defeat in November 1918. After serving as emperor for 30 of the 47 years of the existence of the German Empire, Wilhelm II ultimately lost the support of the military and many of his subjects. The German Empire was converted from a monarchy to an authoritarian republic as a result of the German Revolution of November 1918, at which time Wilhelm abdicated his throne and fled to exile in the Netherlands. He remained there during the German occupation in World War II, and died in 1941.

Biography

Wilhelm was born in Berlin on 27 January 1859 — at the Crown Prince’s Palace — to Victoria, Princess Royal, the eldest daughter of Britain’s Queen Victoria, and Prince Frederick William of Prussia (the future Frederick III). At the time of his birth, his granduncle, Frederick William IV, was king of Prussia. Frederick William IV had been left permanently incapacitated by a series of strokes, and his younger brother Wilhelm was acting as regent. Wilhelm was the first grandchild of his maternal grandparents (Queen Victoria and Prince Albert), but more importantly, he was the first son of the crown prince of Prussia. Upon the death of Frederick William IV in January 1861, Wilhelm’s paternal grandfather (the elder Wilhelm) became king, and the two-year-old Wilhelm became second in the line of succession to Prussia. After 1871, Wilhelm also became second in the line to the newly created German Empire, which, according to the constitution of the German Empire, was ruled by the Prussian king. At the time of his birth, he was also sixth in the line of succession to the British throne, after his maternal uncles and his mother.

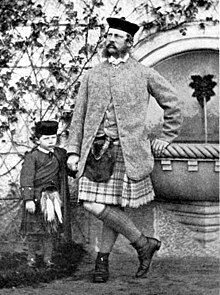

Wilhelm with his father, in Highland dress, in 1862

A traumatic breech birth resulted in Erb’s palsy, which left him with a withered left arm about six inches (15 centimetres) shorter than his right. He tried with some success to conceal this; many photographs show him holding a pair of white gloves in his left hand to make the arm seem longer. In others, he holds his left hand with his right, has his crippled arm on the hilt of a sword, or holds a cane to give the illusion of a useful limb posed at a dignified angle. Historians have suggested that this disability affected his emotional development.

Early years

In 1863, Wilhelm was taken to England to be present at the wedding of his Uncle Bertie (later King Edward VII), and Princess Alexandra of Denmark. Wilhelm attended the ceremony in a Highland costume, complete with a small toy dirk. During the ceremony, the four-year-old became restless. His eighteen-year-old uncle Prince Alfred, charged with keeping an eye on him, told him to be quiet, but Wilhelm drew his dirk and threatened Alfred. When Alfred attempted to subdue him by force, Wilhelm bit him on the leg. His grandmother, Queen Victoria, missed seeing the fracas; to her Wilhelm remained “a clever, dear, good little child, the great favourite of my beloved Vicky”.

His mother, Vicky, was obsessed with his damaged arm, blaming herself for the child’s handicap and insisted that he become a good rider. The thought that he, as heir to the throne, should not be able to ride was intolerable to her. Riding lessons began when Wilhelm was eight and were a matter of endurance for Wilhelm. Over and over, the weeping prince was set on his horse and compelled to go through the paces. He fell off time after time but despite his tears, was set on its back again. After weeks of this he was finally able to maintain his balance.

Wilhelm, from six years of age, was tutored and heavily influenced by the 39-year-old teacher Georg Ernst Hinzpeter. “Hinzpeter”, he later wrote, “was really a good fellow. Whether he was the right tutor for me, I dare not decide. The torments inflicted on me, in this pony riding, must be attributed to my mother.”

Prince Wilhelm as a student at the age of 18 in Kassel. As usual, he is hiding his damaged left hand behind his back.

As a teenager he was educated at Kassel at the Friedrichsgymnasium. In January 1877, Wilhelm finished high school and on his eighteenth birthday received as a present from his grandmother, Queen Victoria, the Order of the Garter. After Kassel he spent four terms at the University of Bonn, studying law and politics. He became a member of the exclusive Corps Borussia Bonn. Wilhelm possessed a quick intelligence, but this was often overshadowed by a cantankerous temper.

| German Royalty |

| House of Hohenzollern |

|---|

|

| Wilhelm II |

|

As a scion of the royal house of Hohenzollern, Wilhelm was exposed from an early age to the military society of the Prussian aristocracy. This had a major impact on him and, in maturity, Wilhelm was seldom seen out of uniform. The hyper-masculine military culture of Prussia in this period did much to frame his political ideals and personal relationships.

Crown Prince Frederick was viewed by his son with a deeply felt love and respect. His father’s status as a hero of the wars of unification was largely responsible for the young Wilhelm’s attitude, as were the circumstances in which he was raised; close emotional contact between father and son was not encouraged. Later, as he came into contact with the Crown Prince’s political opponents, Wilhelm came to adopt more ambivalent feelings toward his father, perceiving the influence of Wilhelm’s mother over a figure who should have been possessed of masculine independence and strength. Wilhelm also idolised his grandfather, Wilhelm I, and he was instrumental in later attempts to foster a cult of the first German Emperor as “Wilhelm the Great”. However, he had a distant relationship with his mother.

Prince Wilhelm posing for a photo taken around 1887. His right hand is holding his left hand, which was affected by Erb’s palsy.

Wilhelm resisted attempts by his parents, especially his mother, to educate him in a spirit of British liberalism. Instead, he agreed with his tutors’ support of autocratic rule, and gradually became thoroughly ‘Prussianized’ under their influence. He thus became alienated from his parents, suspecting them of putting Britain’s interests first. The German Emperor, Wilhelm I, watched as his grandson, guided principally by the Crown Princess Victoria, grew to manhood. When Wilhelm was nearing twenty-one the Emperor decided it was time his grandson should begin the military phase of his preparation for the throne. He was assigned as a lieutenant to the First Regiment of Foot Guards, stationed at Potsdam. “In the Guards,” Wilhelm said, “I really found my family, my friends, my interests – everything of which I had up to that time had to do without.” As a boy and a student, his manner had been polite and agreeable; as an officer, he began to strut and speak brusquely in the tone he deemed appropriate for a Prussian officer.

In many ways, Wilhelm was a victim of his inheritance and of Otto von Bismarck’s machinations. When Wilhelm was in his early twenties, Bismarck tried to separate him from his parents (who opposed Bismarck and his policies) with some success. Bismarck planned to use the young prince as a weapon against his parents in order to retain his own political dominance. Wilhelm thus developed a dysfunctional relationship with his parents, but especially with his English mother. In an outburst in April 1889, Wilhelm angrily implied that “an English doctor killed my father, and an English doctor crippled my arm – which is the fault of my mother”, who allowed no German physicians to attend to herself or her immediate family.

As a young man, Wilhelm fell in love with one of his maternal first cousins, Princess Elisabeth of Hesse-Darmstadt. She turned him down, and would, in time, marry into the Russian imperial family. In 1880 Wilhelm became engaged to Augusta Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein, known as “Dona”. The couple married on 27 February 1881, and remained married for forty years, until her death in 1921. In a period of ten years, between 1882 and 1892, Augusta Victoria would bear Wilhelm seven children, six sons and a daughter.

Beginning in 1884, Bismarck began advocating that Kaiser Wilhelm send his grandson on diplomatic missions, a privilege denied to the Crown Prince. That year, Prince Wilhelm was sent to the court of Tsar Alexander III of Russia in St. Petersburg to attend the coming of age ceremony of the sixteen-year-old Tsarevich Nicholas. Wilhelm’s behaviour did little to ingratiate himself to the tsar. Two years later, Kaiser Wilhelm I took Prince Wilhelm on a trip to meet with Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria-Hungary. In 1886, also, thanks to Herbert von Bismarck, the son of the Chancellor, Prince Wilhelm began to be trained twice a week at the Foreign Ministry. One privilege was denied to Prince Wilhelm: to represent Germany at his maternal grandmother, Queen Victoria’s, Golden Jubilee celebrations in London in 1887.

Accession

Kaiser Wilhelm I died in Berlin on 9 March 1888, and Prince Wilhelm’s father ascended the throne as Frederick III. He was already suffering from an incurable throat cancer and spent all 99 days of his reign fighting the disease before dying. On 15 June of that same year, his 29-year-old son succeeded him as German Emperor and King of Prussia.

Wilhelm in 1905

Although in his youth he had been a great admirer of Otto von Bismarck, Wilhelm’s characteristic impatience soon brought him into conflict with the “Iron Chancellor”, the dominant figure in the foundation of his empire. The new Emperor opposed Bismarck’s careful foreign policy, preferring vigorous and rapid expansion to protect Germany’s “place in the sun”. Furthermore, the young Emperor had come to the throne determined to rule as well as reign, unlike his grandfather. While the letter of the imperial constitution vested executive power in the emperor, Wilhelm I had been content to leave day-to-day administration to Bismarck. Early conflicts between Wilhelm II and his chancellor soon poisoned the relationship between the two men. Bismarck believed that Wilhelm was a lightweight who could be dominated, and he showed scant respect for Wilhelm’s policies in the late 1880s. The final split between monarch and statesman occurred soon after an attempt by Bismarck to implement a far-reaching anti-Socialist law in early 1890.

Break with Bismarck

The impetuous young Kaiser rejected Bismarck’s “peaceful foreign policy” and instead plotted with senior generals to work “in favour of a war of aggression”. Bismarck told an aide, “That young man wants war with Russia, and would like to draw his sword straight away if he could. I shall not be a party to it.” Bismarck, after gaining an absolute majority in the Reichstag in favour of his policies, decided to make the anti-Socialist laws permanent. His Kartell, the majority of the amalgamated Conservative Party and the National Liberal Party, favoured making the laws permanent, with one exception: the police power to expel Socialist agitators from their homes. The Kartell split over this issue and nothing was passed.

As the debate continued, Wilhelm became more and more interested in social problems, especially the treatment of mine workers who went on strike in 1889. He routinely interrupted Bismarck in Council to make clear where he stood on social policy; Bismarck, in turn, sharply disagreed with Wilhelm’s policy and worked to circumvent it. Bismarck, feeling pressured and unappreciated by the young Emperor and undermined by his ambitious advisors, refused to sign a proclamation regarding the protection of workers along with Wilhelm, as was required by the German Constitution.

The final break came as Bismarck searched for a new parliamentary majority, with his Kartell voted from power due to the anti-Socialist bill fiasco. The remaining powers in the Reichstag were the Catholic Centre Party and the Conservative Party. Bismarck wished to form a new bloc with the Centre Party, and invited Ludwig Windthorst, the party’s parliamentary leader, to discuss a coalition; Wilhelm was furious to hear about Windthorst’s visit. In a parliamentary state, the head of government depends on the confidence of the parliamentary majority and has the right to form coalitions to ensure his policies a majority, but in Germany, the Chancellor had to depend on the confidence of the Emperor, and Wilhelm believed that the Emperor had the right to be informed before his ministers’ meeting. After a heated argument at Bismarck’s estate over Imperial authority, Wilhelm stormed out. Bismarck, forced for the first time into a situation he could not use to his advantage, wrote a blistering letter of resignation, decrying Wilhelm’s interference in foreign and domestic policy, which was published only after Bismarck’s death.

Bismarck had sponsored landmark social security legislation, but by 1889–90, he had become disillusioned with the attitude of workers. In particular, he was opposed to wage increases, improving working conditions, and regulating labour relations. Moreover, the Kartell, the shifting political coalition that Bismarck had been able to forge since 1867, had lost a working majority in the Reichstag. At the opening of the Reichstag on 6 May 1890, the Kaiser stated that the most pressing issue was the further enlargement of the bill concerning the protection of the labourer. In 1891, the Reichstag passed the Workers Protection Acts, which improved working conditions, protected women and children and regulated labour relations.

Wilhelm in control

|

|

This section includes a list of general references, but it remains largely unverified because it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Dismissal of Bismarck

Dropping the Pilot”, a cartoon by Sir John Tenniel (1820–1914), published in the British magazine Punch, 29 March 1890, two weeks after Bismarck’s dismissal

Bismarck resigned at Wilhelm II’s insistence in 1890, at the age of 75, to be succeeded as Chancellor of Germany and Minister-President of Prussia by Leo von Caprivi, who in turn was replaced by Chlodwig, Prince of Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst, in 1894. Following the dismissal of Hohenlohe in 1900, Wilhelm appointed the man whom he regarded as “his own Bismarck”, Bernhard von Bülow.

In foreign policy Bismarck had achieved a fragile balance of interests between Germany, France and Russia—peace was at hand and Bismarck tried to keep it that way despite growing popular sentiment against Britain (regarding colonies) and especially against Russia. With Bismarck’s dismissal, the Russians now expected a reversal of policy in Berlin, so they quickly came to terms with France, beginning the process that by 1914 largely isolated Germany.

Silver 5-mark coin of Wilhelm II

In appointing Caprivi and then Hohenlohe, Wilhelm was embarking upon what is known to history as “the New Course”, in which he hoped to exert decisive influence in the government of the empire. There is debate amongst historians as to the precise degree to which Wilhelm succeeded in implementing “personal rule” in this era, but what is clear is the very different dynamic which existed between the Crown and its chief political servant (the Chancellor) in the “Wilhelmine Era”. These chancellors were senior civil servants and not seasoned politician-statesmen like Bismarck. Wilhelm wanted to preclude the emergence of another Iron Chancellor, whom he ultimately detested as being “a boorish old killjoy” who had not permitted any minister to see the Emperor except in his presence, keeping a stranglehold on effective political power. Upon his enforced retirement and until his dying day, Bismarck became a bitter critic of Wilhelm’s policies, but without the support of the supreme arbiter of all political appointments (the Emperor) there was little chance of Bismarck exerting a decisive influence on policy.

Bismarck did manage to create the “Bismarck myth”, the view (which some would argue was confirmed by subsequent events) that Wilhelm II’s dismissal of the Iron Chancellor effectively destroyed any chance Germany had of stable and effective government. In this view, Wilhelm’s “New Course” was characterised far more as the German ship of state going out of control, eventually leading through a series of crises to the carnage of the First and Second World Wars.

Portrait by Philip de László, 1908

In the early twentieth century, Wilhelm began to concentrate upon his real agenda: the creation of a German navy that would rival that of Britain and enable Germany to declare itself a world power. He ordered his military leaders to read Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan’s book, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, and spent hours drawing sketches of the ships that he wanted built. Bülow and Bethmann Hollweg, his loyal chancellors, looked after domestic affairs, while Wilhelm began to spread alarm in the chancellories of Europe with his increasingly eccentric views on foreign affairs.

Promoter of arts and sciences

Wilhelm enthusiastically promoted the arts and sciences, as well as public education and social welfare. He sponsored the Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the promotion of scientific research; it was funded by wealthy private donors and by the state and comprised a number of research institutes in both pure and applied sciences. The Prussian Academy of Sciences was unable to avoid the Kaiser’s pressure and lost some of its autonomy when it was forced to incorporate new programs in engineering, and award new fellowships in engineering sciences as a result of a gift from the Kaiser in 1900.

Wilhelm supported the modernisers as they tried to reform the Prussian system of secondary education, which was rigidly traditional, elitist, politically authoritarian, and unchanged by the progress in the natural sciences. As hereditary Protector of the Order of Saint John, he offered encouragement to the Christian order’s attempts to place German medicine at the forefront of modern medical practice through its system of hospitals, nursing sisterhood and nursing schools, and nursing homes throughout the German Empire. Wilhelm continued as Protector of the Order even after 1918, as the position was in essence attached to the head of the House of Hohenzollern.

Personality

Wilhelm talking with Ethiopians at the Tierpark Hagenbeck in Hamburg in 1909

Historians have frequently stressed the role of Wilhelm’s personality in shaping his reign. Thus, Thomas Nipperdey concludes he was:

gifted, with a quick understanding, sometimes brilliant, with a taste for the modern,—technology, industry, science—but at the same time superficial, hasty, restless, unable to relax, without any deeper level of seriousness, without any desire for hard work or drive to see things through to the end, without any sense of sobriety, for balance and boundaries, or even for reality and real problems, uncontrollable and scarcely capable of learning from experience, desperate for applause and success,—as Bismarck said early on in his life, he wanted every day to be his birthday—romantic, sentimental and theatrical, unsure and arrogant, with an immeasurably exaggerated self-confidence and desire to show off, a juvenile cadet, who never took the tone of the officers’ mess out of his voice, and brashly wanted to play the part of the supreme warlord, full of panicky fear of a monotonous life without any diversions, and yet aimless, pathological in his hatred against his English mother.

Historian David Fromkin states that Wilhelm had a love–hate relationship with Britain. According to Fromkin “From the outset, the half-German side of him was at war with the half-English side. He was wildly jealous of the British, wanting to be British, wanting to be better at being British than the British were, while at the same time hating them and resenting them because he never could be fully accepted by them”.

Langer et al. (1968) emphasise the negative international consequences of Wilhelm’s erratic personality: “He believed in force, and the ‘survival of the fittest’ in domestic as well as foreign politics … William was not lacking in intelligence, but he did lack stability, disguising his deep insecurities by swagger and tough talk. He frequently fell into depressions and hysterics … William’s personal instability was reflected in vacillations of policy. His actions, at home as well as abroad, lacked guidance, and therefore often bewildered or infuriated public opinion. He was not so much concerned with gaining specific objectives, as had been the case with Bismarck, as with asserting his will. This trait in the ruler of the leading Continental power was one of the main causes of the uneasiness prevailing in Europe at the turn-of-the-century”.

Relationships with foreign relatives

As a grandchild of Queen Victoria, Wilhelm was a first cousin of the future King George V of the United Kingdom, as well as of Queens Marie of Romania, Maud of Norway, Victoria Eugenie of Spain, and the Empress Alexandra of Russia. In 1889, Wilhelm’s younger sister, Sophia, married the future King Constantine I of Greece. Wilhelm was infuriated by his sister’s conversion to Greek Orthodoxy; upon her marriage, he attempted to ban her from entering Germany.

The Nine Sovereigns at Windsor for the funeral of King Edward VII, photographed on 20 May 1910. Standing, from left to right: King Haakon VII of Norway, Tsar Ferdinand of the Bulgarians, King Manuel II of Portugal and the Algarve, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany and Prussia, King George I of the Hellenes and King Albert I of the Belgians. Seated, from left to right: King Alfonso XIII of Spain, King George V of the United Kingdom and King Frederick VIII of Denmark.

Wilhelm’s most contentious relationships were with his British relations. He craved the acceptance of his grandmother, Queen Victoria, and of the rest of her family. Despite the fact that his grandmother treated him with courtesy and tact, his other relatives found him arrogant and obnoxious, and they largely denied him acceptance. He had an especially bad relationship with his Uncle Bertie, the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII). Between 1888 and 1901 Wilhelm resented his uncle, himself a mere heir to the British throne, treating Wilhelm not as Emperor of Germany, but merely as another nephew. In turn, Wilhelm often snubbed his uncle, whom he referred to as “the old peacock” and lorded his position as emperor over him. Beginning in the 1890s, Wilhelm made visits to England for Cowes Week on the Isle of Wight and often competed against his uncle in the yacht races. Edward’s wife, the Danish-born Alexandra, first as Princess of Wales and later as Queen, also disliked Wilhelm, never forgetting the Prussian seizure of Schleswig-Holstein from Denmark in the 1860s, as well as being annoyed over Wilhelm’s treatment of his mother. Despite his poor relations with his English relatives, when he received news that Queen Victoria was dying at Osborne House in January 1901, Wilhelm travelled to England and was at her bedside when she died, and he remained for the funeral. He also was present at the funeral of King Edward VII in 1910.

In 1913, Wilhelm hosted a lavish wedding in Berlin for his only daughter, Victoria Louise. Among the guests at the wedding were his cousins Tsar Nicholas II of Russia and King George V, and George’s wife, Queen Mary.

Foreign affairs

1898 Chinese imperialism cartoon: A Mandarin official helplessly looks on as China, depicted as a pie, is about to be carved up by Queen Victoria (Britain), Wilhelm (Germany), Nicholas II (Russia), Marianne (France), and a samurai (Japan)

A 1904 British cartoon commenting on the Entente cordiale: John Bull walking off with Marianne, turning his back on Wilhelm II, whose sabre is shown extending from his coat

Wilhelm with Nicholas II of Russia in 1905, wearing the military uniforms of each other’s army

German foreign policy under Wilhelm II was faced with a number of significant problems. Perhaps the most apparent was that Wilhelm was an impatient man, subjective in his reactions and affected strongly by sentiment and impulse. He was personally ill-equipped to steer German foreign policy along a rational course. It is now widely recognised that the various spectacular acts which Wilhelm undertook in the international sphere were often partially encouraged by the German foreign policy elite. There were a number of notorious examples, such as the Kruger telegram of 1896 in which Wilhelm congratulated President Paul Kruger of the Transvaal Republic on the suppression of the British Jameson Raid, thus alienating British public opinion.

British public opinion had been quite favourable towards the Kaiser in his first twelve years on the throne, but it turned sour in the late 1890s. During the First World War, he became the central target of British anti-German propaganda and the personification of a hated enemy.

Wilhelm invented and spread fears of a yellow peril trying to interest other European rulers in the perils they faced by invading China; few other leaders paid attention. Wilhelm used the Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War to try to incite fear in the west of the yellow peril that they faced by a resurgent Japan, which Wilhelm claimed would ally with China to overrun the west. Under Wilhelm, Germany invested in strengthening its colonies in Africa and the Pacific, but few became profitable and all were lost during the First World War. In South West Africa (now Namibia), a native revolt against German rule led to the Herero and Namaqua Genocide, although Wilhelm eventually ordered it to be stopped.

One of the few times when Wilhelm succeeded in personal diplomacy was when in 1900 he supported the marriage of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria to Countess Sophie Chotek, against the wishes of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria.

A domestic triumph for Wilhelm was when his daughter Victoria Louise married the Duke of Brunswick in 1913; this helped heal the rift between the House of Hanover and the House of Hohenzollern that had followed the annexation of Hanover by Prussia in 1866.

Political visits to the Ottoman Empire

Wilhelm in Jerusalem during his state visit to the Ottoman Empire, 1898

In his first visit to Istanbul in 1889, Wilhelm secured the sale of German-made rifles to the Ottoman Army. Later on, he had his second political visit to the Ottoman Empire as a guest of Sultan Abdülhamid II. The Kaiser started his journey to the Ottoman Eyalets with Istanbul on 16 October 1898; then he went by yacht to Haifa on 25 October. After visiting Jerusalem and Bethlehem, the Kaiser went back to Jaffa to embark to Beirut, where he took the train passing Aley and Zahlé to reach Damascus on 7 November. While visiting the Mausoleum of Saladin the following day, the Kaiser made a speech:

In the face of all the courtesies extended to us here, I feel that I must thank you, in my name as well as that of the Empress, for them, for the hearty reception given us in all the towns and cities we have touched, and particularly for the splendid welcome extended to us by this city of Damascus. Deeply moved by this imposing spectacle, and likewise by the consciousness of standing on the spot where held sway one of the most chivalrous rulers of all times, the great Sultan Saladin, a knight sans peur et sans reproche, who often taught his adversaries the right conception of knighthood, I seize with joy the opportunity to render thanks, above all to the Sultan Abdul Hamid for his hospitality. May the Sultan rest assured, and also the three hundred million Mohammedans scattered over the globe and revering in him their caliph, that the German Emperor will be and remain at all times their friend.

— Kaiser Wilhelm II,

On 10 November, Wilhelm went to visit Baalbek before heading to Beirut to board his ship back home on 12 November. In his second visit, Wilhelm secured a promise for German companies to construct the Berlin–Baghdad railway, and had the German Fountain constructed in Istanbul to commemorate his journey.

His third visit was on 15 October 1917, as the guest of Sultan Mehmed V.

Hun speech of 1900

The Boxer Rebellion, an anti-western uprising in China, was put down in 1900 by an international force of British, French, Russian, Austrian, Italian, American, Japanese, and German troops. The Germans, however, forfeited any prestige that they might have gained for their participation by arriving only after the British and Japanese forces had taken Peking, the site of the fiercest fighting. Moreover, the poor impression left by the German troops’ late arrival was made worse by the Kaiser’s ill-conceived farewell address, in which he commanded them, in the spirit of the Huns, to be merciless in battle. Wilhelm delivered this speech in Bremerhaven on 27 July 1900, addressing German troops who were departing to suppress the Boxer Rebellion in China. The speech was infused with Wilhelm’s fiery and chauvinistic rhetoric and clearly expressed his vision of German imperial power. There were two versions of the speech. The Foreign Office issued an edited version, making sure to omit one particularly incendiary paragraph that they regarded as diplomatically embarrassing. The edited version was this:

Great overseas tasks have fallen to the new German Empire, tasks far greater than many of my countrymen expected. The German Empire has, by its very character, the obligation to assist its citizens if they are being set upon in foreign lands. The tasks that the old Roman Empire of the German nation was unable to accomplish, the new German Empire is in a position to fulfill. The means that make this possible is our army.

It has been built up during thirty years of faithful, peaceful labor, following the principles of my blessed grandfather. You, too, have received your training in accordance with these principles, and by putting them to the test before the enemy, you should see whether they have proved their worth in you. Your comrades in the navy have already passed this test; they have shown that the principles of your training are sound, and I am also proud of the praise that your comrades have earned over there from foreign leaders. It is up to you to emulate them.

A great task awaits you: you are to revenge the grievous injustice that has been done. The Chinese have overturned the law of nations; they have mocked the sacredness of the envoy, the duties of hospitality in a way unheard of in world history. It is all the more outrageous that this crime has been committed by a nation that takes pride in its ancient culture. Show the old Prussian virtue. Present yourselves as Christians in the cheerful endurance of suffering. May honor and glory follow your banners and arms. Give the whole world an example of manliness and discipline.

You know full well that you are to fight against a cunning, brave, well-armed, and cruel enemy. When you encounter him, know this: no quarter will be given. Prisoners will not be taken. Exercise your arms such that for a thousand years no Chinese will dare to look cross-eyed at a German. Maintain discipline. May God’s blessing be with you, the prayers of an entire nation and my good wishes go with you, each and every one. Open the way to civilization once and for all! Now you may depart! Farewell, comrades!

The official version omitted the following passage from which the speech derives its name:

Should you encounter the enemy, he will be defeated! No quarter will be given! Prisoners will not be taken! Whoever falls into your hands is forfeited. Just as a thousand years ago the Huns under their King Attila made a name for themselves, one that even today makes them seem mighty in history and legend, may the name German be affirmed by you in such a way in China that no Chinese will ever again dare to look cross-eyed at a German.

The term “Hun” later became the favoured epithet of Allied anti-German war propaganda during the First World War.

Eulenberg Scandal

In the years 1906–09, journalist Maximilian Harden published revelations of homosexual activity involving ministers, courtiers, army officers, and Wilhelm’s closest friend and advisor, Prince Philipp zu Eulenberg. This resulted in a succession of scandals, trials, and suicides. Harden, like some in the upper echelons of the military and Foreign Office, resented Eulenberg’s approval of the Anglo-French Entente, and also his encouragement of Wilhelm to rule personally. The scandal led to Wilhelm suffering a nervous breakdown, and the removal of Eulenberg and others of his circle from the court. The view that Wilhelm was a deeply repressed homosexual is increasingly supported by scholars: certainly, he never came to terms with his feelings for Eulenberg. Historians have linked the Eulenberg scandal to a fundamental shift in German policy that heightened its military aggressiveness and ultimately contributed to World War I.

Moroccan Crisis

One of Wilhelm’s diplomatic blunders sparked the Moroccan Crisis of 1905, when he made a spectacular visit to Tangier, in Morocco on 31 March 1905. He conferred with representatives of Sultan Abdelaziz of Morocco. The Kaiser proceeded to tour the city on the back of a white horse. The Kaiser declared he had come to support the sovereignty of the Sultan—a statement which amounted to a provocative challenge to French influence in Morocco. The Sultan subsequently rejected a set of French-proposed governmental reforms and invited major world powers to a conference which would advise him on necessary reforms.

The Kaiser’s presence was seen as an assertion of German interests in Morocco, in opposition to those of France. In his speech, he even made remarks in favour of Moroccan independence, and this led to friction with France, which was expanding its colonial interests in Morocco, and to the Algeciras Conference, which served largely to further isolate Germany in Europe.

Daily Telegraph affair

Wilhelm and Winston Churchill during a military autumn manoeuvre near Breslau, Silesia (Wrocław, Poland) in 1906

Wilhelm’s most damaging personal blunder cost him much of his prestige and power and had a far greater impact in Germany than overseas. The Daily Telegraph Affair of 1908 involved the publication in Germany of an interview with a British daily newspaper that included wild statements and diplomatically damaging remarks. Wilhelm had seen the interview as an opportunity to promote his views and ideas on Anglo-German friendship, but due to his emotional outbursts during the course of the interview, he ended up further alienating not only the British, but also the French, Russians, and Japanese. He implied, among other things, that the Germans cared nothing for the British; that the French and Russians had attempted to incite Germany to intervene in the Second Boer War; and that the German naval buildup was targeted against the Japanese, not Britain. One memorable quotation from the interview was, “You English are mad, mad, mad as March hares.” The effect in Germany was quite significant, with serious calls for his abdication. Wilhelm kept a very low profile for many months after the Daily Telegraph fiasco, but later exacted his revenge by forcing the resignation of the chancellor, Prince Bülow, who had abandoned the Emperor to public scorn by not having the transcript edited before its German publication. The Daily Telegraph crisis deeply wounded Wilhelm’s previously unimpaired self-confidence, and he soon suffered a severe bout of depression from which he never fully recovered. He lost much of the influence he had previously exercised in domestic and foreign policy.

Caricature by Olaf Gulbransson 1909: “Manoeuvre: Emperor William II explains the enemy’s positions to Prince Ludwig of Bavaria”

Nothing Wilhelm did in the international arena was of more influence than his decision to pursue a policy of massive naval construction. A powerful navy was Wilhelm’s pet project. He had inherited from his mother a love of the British Royal Navy, which was at that time the world’s largest. He once confided to his uncle, the Prince of Wales, that his dream was to have a “fleet of my own some day”. Wilhelm’s frustration over his fleet’s poor showing at the Fleet Review at his grandmother Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations, combined with his inability to exert German influence in South Africa following the dispatch of the Kruger telegram, led to Wilhelm taking definitive steps toward the construction of a fleet to rival that of his British cousins. Wilhelm was fortunate to be able to call on the services of the dynamic naval officer Alfred von Tirpitz, whom he appointed to the head of the Imperial Naval Office in 1897.

The new admiral had conceived of what came to be known as the “Risk Theory” or the Tirpitz Plan, by which Germany could force Britain to accede to German demands in the international arena through the threat posed by a powerful battlefleet concentrated in the North Sea. Tirpitz enjoyed Wilhelm’s full support in his advocacy of successive naval bills of 1897 and 1900, by which the German navy was built up to contend with that of the British Empire. Naval expansion under the Fleet Acts eventually led to severe financial strains in Germany by 1914, as by 1906 Wilhelm had committed his navy to construction of the much larger, more expensive dreadnought type of battleship.

In 1889 Wilhelm reorganised top-level control of the navy by creating a Naval Cabinet (Marine-Kabinett) equivalent to the German Imperial Military Cabinet which had previously functioned in the same capacity for both the army and navy. The Head of the Naval Cabinet was responsible for promotions, appointments, administration, and issuing orders to naval forces. Captain Gustav von Senden-Bibran was appointed as the first head and remained so until 1906. The existing Imperial admiralty was abolished, and its responsibilities divided between two organisations. A new position was created, equivalent to the supreme commander of the army: the Chief of the High Command of the Admiralty, or Oberkommando der Marine, was responsible for ship deployments, strategy and tactics. Vice-Admiral Max von der Goltz was appointed in 1889 and remained in post until 1895. Construction and maintenance of ships and obtaining supplies was the responsibility of the State Secretary of the Imperial Navy Office (Reichsmarineamt), responsible to the Imperial Chancellor and advising the Reichstag on naval matters. The first appointee was Rear Admiral Karl Eduard Heusner, followed shortly by Rear Admiral Friedrich von Hollmann from 1890 to 1897. Each of these three heads of department reported separately to Wilhelm.

In addition to the expansion of the fleet, the Kiel Canal was opened in 1895, enabling faster movements between the North Sea and the Baltic Sea.

World War I

Historians typically argue that Wilhelm was largely confined to ceremonial duties during the war—there were innumerable parades to review and honours to award. “The man who in peace had believed himself omnipotent became in war a ‘shadow Kaiser’, out of sight, neglected, and relegated to the sidelines.”

The Sarajevo crisis

Wilhelm with the Grand Duke of Baden, Prince Oskar of Prussia, the Grand Duke of Hesse, the Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Prince Louis of Bavaria, Prince Max of Baden and his son, Crown Prince Wilhelm, at pre-war military manoeuvres in autumn 1909

A composite image of Wilhelm with German generals

Wilhelm was a friend of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, and he was deeply shocked by his assassination on 28 June 1914. Wilhelm offered to support Austria-Hungary in crushing the Black Hand, the secret organisation that had plotted the killing, and even sanctioned the use of force by Austria against the perceived source of the movement—Serbia (this is often called “the blank cheque”). He wanted to remain in Berlin until the crisis was resolved, but his courtiers persuaded him instead to go on his annual cruise of the North Sea on 6 July 1914. Wilhelm made erratic attempts to stay on top of the crisis via telegram, and when the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum was delivered to Serbia, he hurried back to Berlin. He reached Berlin on 28 July, read a copy of the Serbian reply, and wrote on it:

A brilliant solution—and in barely 48 hours! This is more than could have been expected. A great moral victory for Vienna; but with it every pretext for war falls to the ground, and Giesl had better have stayed quietly at Belgrade. On this document, I should never have given orders for mobilisation.

Unknown to the Emperor, Austro-Hungarian ministers and generals had already convinced the 83-year-old Franz Joseph I of Austria to sign a declaration of war against Serbia. As a direct consequence, Russia began a general mobilisation to attack Austria in defence of Serbia.

July 1914

Wilhelm conversing with the victor of Liège, General Otto von Emmich; in the background the generals Hans von Plessen (middle) and Moriz von Lyncker (right)

On the night of 30 July, when handed a document stating that Russia would not cancel its mobilisation, Wilhelm wrote a lengthy commentary containing these observations:

… For I no longer have any doubt that England, Russia and France have agreed among themselves—knowing that our treaty obligations compel us to support Austria—to use the Austro-Serb conflict as a pretext for waging a war of annihilation against us … Our dilemma over keeping faith with the old and honourable Emperor has been exploited to create a situation which gives England the excuse she has been seeking to annihilate us with a spurious appearance of justice on the pretext that she is helping France and maintaining the well-known Balance of Power in Europe, i.e., playing off all European States for her own benefit against us.

More recent British authors state that Wilhelm II really declared, “Ruthlessness and weakness will start the most terrifying war of the world, whose purpose is to destroy Germany. Because there can no longer be any doubts, England, France and Russia have conspired themselves together to fight an annihilation war against us”.

When it became clear that Germany would experience a war on two fronts and that Britain would enter the war if Germany attacked France through neutral Belgium, the panic-stricken Wilhelm attempted to redirect the main attack against Russia. When Helmuth von Moltke (the younger) (who had chosen the old plan from 1905, made by General von Schlieffen for the possibility of German war on two fronts) told him that this was impossible, Wilhelm said: “Your uncle would have given me a different answer!” Wilhelm is also reported to have said, “To think that George and Nicky should have played me false! If my grandmother had been alive, she would never have allowed it.” In the original Schlieffen plan, Germany would attack the (supposed) weaker enemy first, meaning France. The plan supposed that it would take a long time before Russia was ready for war. Defeating France had been easy for Prussia in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. At the 1914 border between France and Germany, an attack at this more southern part of France could be stopped by the French fortress along the border. However, Wilhelm II stopped any invasion of the Netherlands.

Shadow-Kaiser

Hindenburg, Wilhelm, and Ludendorff in January 1917

Wilhelm’s role in wartime was one of ever-decreasing power as he increasingly handled awards ceremonies and honorific duties. The high command continued with its strategy even when it was clear that the Schlieffen plan had failed. By 1916 the Empire had effectively become a military dictatorship under the control of Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff. Increasingly cut off from reality and the political decision-making process, Wilhelm vacillated between defeatism and dreams of victory, depending upon the fortunes of his armies. Nevertheless, Wilhelm still retained the ultimate authority in matters of political appointment, and it was only after his consent had been gained that major changes to the high command could be effected. Wilhelm was in favour of the dismissal of Helmuth von Moltke the Younger in September 1914 and his replacement by Erich von Falkenhayn. In 1917, Hindenburg and Ludendorff decided that Bethman-Hollweg was no longer acceptable to them as Chancellor and called upon the Kaiser to appoint somebody else. When asked whom they would accept, Ludendorff recommended Georg Michaelis, a nonentity whom he barely knew. Despite this, the Kaiser accepted the suggestion. Upon hearing in July 1917 that his cousin George V had changed the name of the British royal house to Windsor, Wilhelm remarked that he planned to see Shakespeare’s play The Merry Wives of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. The Kaiser’s support collapsed completely in October–November 1918 in the army, in the civilian government, and in German public opinion, as President Woodrow Wilson made clear that the Kaiser could no longer be a party to peace negotiations. That year also saw Wilhelm sickened during the worldwide 1918 flu pandemic, though he survived.

Abdication and flight

| Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Statement of Abdication

|

Wilhelm was at the Imperial Army headquarters in Spa, Belgium, when the uprisings in Berlin and other centres took him by surprise in late 1918. Mutiny among the ranks of his beloved Kaiserliche Marine, the imperial navy, profoundly shocked him. After the outbreak of the German Revolution, Wilhelm could not make up his mind whether or not to abdicate. Up to that point, he accepted that he would likely have to give up the imperial crown, but still hoped to retain the Prussian kingship. However, this was impossible under the imperial constitution. Wilhelm thought he ruled as emperor in a personal union with Prussia. In truth, the constitution defined the empire as a confederation of states under the permanent presidency of Prussia. The imperial crown was thus tied to the Prussian crown, meaning that Wilhelm could not renounce one crown without renouncing the other.

Wilhelm’s hope of retaining at least one of his crowns was revealed as unrealistic when, in the hope of preserving the monarchy in the face of growing revolutionary unrest, Chancellor Prince Max of Baden announced Wilhelm’s abdication of both titles on 9 November 1918. Prince Max himself was forced to resign later the same day, when it became clear that only Friedrich Ebert, leader of the SPD, could effectively exert control. Later that day, one of Ebert’s secretaries of state (ministers), Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann, proclaimed Germany a republic.

Wilhelm consented to the abdication only after Ludendorff’s replacement, General Wilhelm Groener, had informed him that the officers and men of the army would march back in good order under Hindenburg’s command, but would certainly not fight for Wilhelm’s throne on the home front. The monarchy’s last and strongest support had been broken, and finally even Hindenburg, himself a lifelong monarchist, was obliged, with some embarrassment, to advise the Emperor to give up the crown. Subsequently, Bismarck had predicted: “Jena came twenty years after the death of Frederick the Great; the crash will come twenty years after my departure if things go on like this.”

On 10 November, Wilhelm crossed the border by train and went into exile in the Netherlands, which had remained neutral throughout the war. Upon the conclusion of the Treaty of Versailles in early 1919, Article 227 expressly provided for the prosecution of Wilhelm “for a supreme offence against international morality and the sanctity of treaties”, but the Dutch government refused to extradite him, despite appeals from the Allies. King George V wrote that he looked on his cousin as “the greatest criminal in history”, but opposed Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s proposal to “hang the Kaiser”.

It was reported, however, that there was little zeal in Britain to prosecute. On 1 January 1920, it was stated in official circles in London that Great Britain would “welcome refusal by Holland to deliver the former kaiser for trial,” and it was hinted that this had been conveyed to the Dutch government through diplomatic channels.

- ”Punishment of the former kaiser and other German war criminals is worrying Great Britain little, it was said. As a matter of form, however, the British and French governments were expected to request Holland for the former kaiser’s extradition. Holland, it was said, will refuse on the ground of constitutional provisions covering the case and then the matter will be dropped. The request for extradition will not be based on genuine desire on the part of British officials to bring the kaiser to trial, according to authoritative information, but is considered necessary formality to ‘save the face’ of politicians who promised to see that Wilhelm was punished for his crimes.”

President Woodrow Wilson of the United States opposed extradition, arguing that prosecuting Wilhelm would destabilise international order and lose the peace.

Wilhelm first settled in Amerongen, where on 28 November he issued a belated statement of abdication from both the Prussian and imperial thrones, thus formally ending the Hohenzollerns’ 500-year rule over Prussia. Accepting the reality that he had lost both of his crowns for good, he gave up his rights to “the throne of Prussia and to the German Imperial throne connected therewith.” He also released his soldiers and officials in both Prussia and the empire from their oath of loyalty to him. He purchased a country house in the municipality of Doorn, known as Huis Doorn, and moved in on 15 May 1920. This was to be his home for the remainder of his life. The Weimar Republic allowed Wilhelm to remove twenty-three railway wagons of furniture, twenty-seven containing packages of all sorts, one bearing a car and another a boat, from the New Palace at Potsdam.

Life in exile

In 1922, Wilhelm published the first volume of his memoirs—a very slim volume that insisted he was not guilty of initiating the Great War, and defended his conduct throughout his reign, especially in matters of foreign policy. For the remaining twenty years of his life, he entertained guests (often of some standing) and kept himself updated on events in Europe. He grew a beard and allowed his famous moustache to droop, adopting a style very similar to that of his cousins King George V and Tsar Nicholas II, (and still worn by Prince Michael of Kent today). He also learned the Dutch language. Wilhelm developed a penchant for archaeology while residing at the Corfu Achilleion, excavating at the site of the Temple of Artemis in Corfu, a passion he retained in his exile. He had bought the former Greek residence of Empress Elisabeth after her murder in 1898. He also sketched plans for grand buildings and battleships when he was bored. In exile, one of Wilhelm’s greatest passions was hunting, and he killed thousands of animals, both beast and bird. Much of his time was spent chopping wood and thousands of trees were chopped down during his stay at Doorn.

Wealth

Wilhelm II was seen as the richest man in the Germany before 1914. After his abdication he retained substantial wealth. It was reported that at least 60 railway wagons were needed to carry his furniture, art, porcelain and silver from Germany to the Netherlands. The kaiser retained substantial cash reserves and as well as several palaces. After 1945, the Hohenzollerns’ forests, farms, factories and palaces in what became East Germany were expropriated and thousands of artworks were subsumed into state-owned museums.

Views on Nazism

In the early 1930s, Wilhelm apparently hoped that the successes of the German Nazi Party would stimulate interest in a restoration of the monarchy, with his eldest grandson as the fourth Kaiser. His second wife, Hermine, actively petitioned the Nazi government on her husband’s behalf. However, Adolf Hitler, himself a veteran of the First World War, like other leading Nazis, felt nothing but contempt for the man they blamed for Germany’s greatest defeat, and the petitions were ignored. Though he played host to Hermann Göring at Doorn on at least one occasion, Wilhelm grew to distrust Hitler. Hearing of the murder of the wife of former Chancellor Schleicher, he said “We have ceased to live under the rule of law and everyone must be prepared for the possibility that the Nazis will push their way in and put them up against the wall!”

Wilhelm was also appalled at the Kristallnacht of 9–10 November 1938, saying “I have just made my views clear to Auwi in the presence of his brothers. He had the nerve to say that he agreed with the Jewish pogroms and understood why they had come about. When I told him that any decent man would describe these actions as gangsterisms, he appeared totally indifferent. He is completely lost to our family”. Wilhelm also stated, “For the first time, I am ashamed to be a German.”

“There’s a man alone, without family, without children, without God … He builds legions, but he doesn’t build a nation. A nation is created by families, a religion, traditions: it is made up out of the hearts of mothers, the wisdom of fathers, the joy and the exuberance of children … For a few months I was inclined to believe in National Socialism. I thought of it as a necessary fever. And I was gratified to see that there were, associated with it for a time, some of the wisest and most outstanding Germans. But these, one by one, he has got rid of or even killed … He has left nothing but a bunch of shirted gangsters! This man could bring home victories to our people each year, without bringing them either glory or danger. But of our Germany, which was a nation of poets and musicians, of artists and soldiers, he has made a nation of hysterics and hermits, engulfed in a mob and led by a thousand liars or fanatics.” ― Wilhelm on Hitler, December 1938.

In the wake of the German victory over Poland in September 1939, Wilhelm’s adjutant, General von Dommes, wrote on his behalf to Hitler, stating that the House of Hohenzollern “remained loyal” and noted that nine Prussian Princes (one son and eight grandchildren) were stationed at the front, concluding “because of the special circumstances that require residence in a neutral foreign country, His Majesty must personally decline to make the aforementioned comment. The Emperor has therefore charged me with making a communication.” Wilhelm greatly admired the success which Hitler was able to achieve in the opening months of the Second World War, and personally sent a congratulatory telegram when the Netherlands surrendered in May 1940: “My Fuhrer, I congratulate you and hope that under your marvellous leadership the German monarchy will be restored completely.” Hitler was reportedly exasperated and bemused, and remarked to Linge, his valet, “What an idiot!” In another telegram to Hitler upon the fall of Paris a month later, Wilhelm stated “Congratulations, you have won using my troops.” In a letter to his daughter Victoria Louise, Duchess of Brunswick, he wrote triumphantly, “Thus is the pernicious Entente Cordiale of Uncle Edward VII brought to nought.” Nevertheless, after the German conquest of the Netherlands in 1940, the aging Wilhelm retired completely from public life. In May 1940, when Hitler invaded the Netherlands, Wilhelm declined an offer from Churchill of asylum in Britain, preferring to remain at Huis Doorn.

Anti-England, anti-Semitic, and anti-Freemason views

During his last year at Doorn, Wilhelm believed that Germany was the land of monarchy and therefore of Christ, and that England was the land of liberalism and therefore of Satan and the Antichrist. He argued that the English ruling classes were “Freemasons thoroughly infected by Juda”. Wilhelm asserted that the “British people must be liberated from Antichrist Juda. We must drive Juda out of England just as he has been chased out of the Continent.”

He believed the Freemasons and Jews had caused the two world wars, aiming at a world Jewish empire with British and American gold, but that “Juda’s plan has been smashed to pieces and they themselves swept out of the European Continent!” Continental Europe was now, Wilhelm wrote, “consolidating and closing itself off from British influences after the elimination of the British and the Jews!” The end result would be a “U.S. of Europe!” In a 1940 letter to his sister Princess Margaret, Wilhelm wrote: “The hand of God is creating a new world & working miracles… We are becoming the U.S. of Europe under German leadership, a united European Continent.” He added: “The Jews being thrust out of their nefarious positions in all countries, whom they have driven to hostility for centuries.”

Also in 1940 came what would have been his mother’s 100th birthday, on which he wrote ironically to a friend “Today the 100th birthday of my mother! No notice is taken of it at home! No ‘Memorial Service’ or … committee to remember her marvellous work for the … welfare of our German people … Nobody of the new generation knows anything about her.”

-

Wilhelm in Amerongen, 1919

-

Huis Doorn in 1925

-

Wilhelm in 1933

-

Huis Doorn in October 2004

Death

The funeral of Wilhelm II

Wilhelm’s tomb at Huis Doorn

Wilhelm died of a pulmonary embolism in Doorn, Netherlands, on 4 June 1941, at the age of 82, just weeks before the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union. Despite his personal animosity toward Wilhelm, Hitler wanted to bring his body back to Berlin for a state funeral, as Wilhelm was a symbol of Germany and Germans during the previous World War. Hitler felt that such a funeral would demonstrate to the Germans the direct descent of the Third Reich from the old German Empire. However, Wilhelm’s wishes never to return to Germany until the restoration of the monarchy were respected, and the Nazi occupation authorities granted him a small military funeral, with a few hundred people present. The mourners included August von Mackensen, fully dressed in his old imperial Life Hussars uniform, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, General Curt Haase and Reichskommissar for the Netherlands Arthur Seyss-Inquart, along with a few other military advisers. However, Wilhelm’s request that the swastika and other Nazi regalia not be displayed at his funeral was ignored, and they are featured in the photographs of the event taken by a Dutch photographer.

Wilhelm was buried in a mausoleum in the grounds of Huis Doorn, which has since become a place of pilgrimage for German monarchists. A few of these gather there every year on the anniversary of his death to pay their homage to the last German Emperor.

Historiography

Three trends have characterised the writing about Wilhelm. First, the court-inspired writers considered him a martyr and a hero, often uncritically accepting the justifications provided in the Kaiser’s own memoirs. Second, there came those who judged Wilhelm to be completely unable to handle the great responsibilities of his position, a ruler too reckless to deal with power. Third, after 1950, later scholars have sought to transcend the passions of the early 20th century and attempted an objective portrayal of Wilhelm and his rule.

On 8 June 1913, a year before the Great War began, The New York Times published a special supplement devoted to the 25th anniversary of the Kaiser’s accession. The banner headline read: “Kaiser, 25 Years a Ruler, Hailed as Chief Peacemaker”. The accompanying story called him “the greatest factor for peace that our time can show”, and credited Wilhelm with frequently rescuing Europe from the brink of war. Until the late 1950s, the Kaiser was depicted by most historians as a man of considerable influence. Partly that was a deception by German officials. For example, President Theodore Roosevelt believed the Kaiser was in control of German foreign policy because Hermann Speck von Sternburg, the German ambassador in Washington and a personal friend of Roosevelt, presented to the president messages from Chancellor von Bülow as messages from the Kaiser. Later historians downplayed his role, arguing that senior officials learned to work around him. More recently historian John C. G. Röhl has portrayed Wilhelm as the key figure in understanding the recklessness and downfall of Imperial Germany. Thus, the argument is made that the Kaiser played a major role in promoting the policies of naval and colonial expansion that caused the sharp deterioration in Germany’s relations with Britain before 1914.

Marriages and issue

Wilhelm and his first wife, Augusta Viktoria

German State Prussia, Wedding Medal 1881 Prince Wilhelm and Auguste Victoria, obverse

The reverse shows the couple in Medieval costumes in front of 3 squires carrying the shields of Prussia, Germany, and Schleswig-Holstein

Wilhelm and his first wife, Princess Augusta Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein, were married on 27 February 1881. They had seven children:

| Name | Birth | Death | Spouse | Children |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crown Prince Wilhelm | 6 May 1882 | 20 July 1951 | Duchess Cecilie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin | Prince Wilhelm (1906–1940) Prince Louis Ferdinand (1907–1994) Prince Hubertus (1909–1950) Prince Frederick (1911–1966) Princess Alexandrine (1915–1980) Princess Cecilie (1917–1975) |

| Prince Eitel Friedrich | 7 July 1883 | 8 December 1942 | Duchess Sophia Charlotte of Oldenburg | |

| Prince Adalbert | 14 July 1884 | 22 September 1948 | Princess Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen | Princess Victoria Marina (1915) Princess Victoria Marina (1917–1981) Prince Wilhelm Victor (1919–1989) |

| Prince August Wilhelm | 29 January 1887 | 25 March 1949 | Princess Alexandra Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg | Prince Alexander Ferdinand (1912–1985) |

| Prince Oskar | 27 July 1888 | 27 January 1958 | Countess Ina Marie von Bassewitz | Prince Oskar (1915–1939) Prince Burchard (1917–1988) Princess Herzeleide (1918–1989) Prince Wilhelm-Karl (1922–2007) |

| Prince Joachim | 17 December 1890 | 18 July 1920 | Princess Marie-Auguste of Anhalt | Prince Karl Franz (1916–1975) |

| Princess Victoria Louise | 13 September 1892 | 11 December 1980 | Ernest Augustus, Duke of Brunswick | Prince Ernest Augustus (1914–1987) Prince George William (1915–2006) Princess Frederica (1917–1981) Prince Christian Oscar (1919–1981) Prince Welf Henry (1923–1997) |

Empress Augusta, known affectionately as “Dona”, was a constant companion to Wilhelm, and her death on 11 April 1921 was a devastating blow. It also came less than a year after their son Joachim committed suicide.

Remarriage

With second wife, Hermine, and her daughter, Princess Henriette

The following January, Wilhelm received a birthday greeting from a son of the late Prince Johann George Ludwig Ferdinand August Wilhelm of Schönaich-Carolath. The 63-year-old Wilhelm invited the boy and his mother, Princess Hermine Reuss of Greiz, to Doorn. Wilhelm found Hermine very attractive, and greatly enjoyed her company. The couple were wed in Doorn on 9 November 1922, despite the objections of Wilhelm’s monarchist supporters and his children. Hermine’s daughter, Princess Henriette, married the late Prince Joachim’s son, Karl Franz Josef, in 1940, but divorced in 1946. Hermine remained a constant companion to the aging former emperor until his death.

Religion

Own views

In accordance with his role as the King of Prussia, Emperor Wilhelm II was a Lutheran member of the Evangelical State Church of Prussia’s older Provinces. It was a United Protestant denomination, bringing together Reformed and Lutheran believers.

Attitude towards Islam

Wilhelm II was on friendly terms with the Muslim world. He described himself as a “friend” to “300 million Mohammedans”. Following his trip to Constantinople (which he visited three times – an unbeaten record for any European monarch) in 1898, Wilhelm II wrote to Nicholas II that, “If I had come there without any religion at all, I certainly would have turned Mohammedan!” Written in response to the political competition between the Christian sects to build bigger and grander churches and monuments which made the sects appear idolatrous and turned Muslims away from the Christian message.

Antisemitism

Kaiser Wilhelm II with Enver Pasha, October 1917. Enver was one of the main perpetrators of the Armenian Genocide.

Wilhelm’s biographer Lamar Cecil identified Wilhelm’s “curious but well-developed anti-Semitism”, noting that in 1888 a friend of Wilhelm “declared that the young Kaiser’s dislike of his Hebrew subjects, one rooted in a perception that they possessed an overweening influence in Germany, was so strong that it could not be overcome”. Cecil concludes:

- Wilhelm never changed, and throughout his life he believed that Jews were perversely responsible, largely through their prominence in the Berlin press and in leftist political movements, for encouraging opposition to his rule. For individual Jews, ranging from rich businessmen and major art collectors to purveyors of elegant goods in Berlin stores, he had considerable esteem, but he prevented Jewish citizens from having careers in the army and the diplomatic corps and frequently used abusive language against them.

In 1918, Wilhelm suggested a campaign against the “Jew-Bolsheviks” in the Baltic states, citing the example of what Turks had done to the Armenians a few years earlier.

On 2 December 1919, Wilhelm wrote to Field Marshal August von Mackensen, denouncing his own abdication as the “deepest, most disgusting shame ever perpetrated by a person in history, the Germans have done to themselves … egged on and misled by the tribe of Judah … Let no German ever forget this, nor rest until these parasites have been destroyed and exterminated from German soil!” Wilhelm advocated a “regular international all-worlds pogrom à la Russe” as “the best cure” and further believed that Jews were a “nuisance that humanity must get rid of some way or other. I believe the best thing would be gas!”

Documentaries and films

- William II. – The last days of the German Monarchy (original title: “Wilhelm II. – Die letzten Tage des Deutschen Kaiserreichs”), about the abdication and flight of the last German Kaiser. Germany/Belgium, 2007. Produced by seelmannfilm and German Television. Written and directed by Christoph Weinert.

- Queen Victoria and the Crippled Kaiser, Channel 4, Secret History Series 13; first broadcast 17 November 2013

- Barry Foster plays Wilhelm II in several episodes of the 1974 BBC TV series Fall of Eagles.

- Rupert Julian played Wilhelm II in the 1918 Hollywood propaganda film The Kaiser, the Beast of Berlin.

- Alfred Struwe played Wilhelm in the 1987 Polish historical drama film Magnat.

- Robert Stadlober plays a young crown prince Wilhelm and friend of Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria in the acclaimed 2006 film The Crown Prince (Kronprinz Rudolf).

- Christopher Plummer played Wilhelm II in the 2016 fictitious romantic war drama The Exception.

Orders and decorations

Portrait by Max Koner (1890). Wilhelm wears the collar and mantle of the Prussian Order of the Black Eagle and, at his throat, the Protector’s diamond-studded cross of the Order of Saint John (Bailiwick of Brandenburg).

- German honours

Prussia:

Prussia:

- Knight of the Black Eagle, 27 January 1869; with Collar, 1877

- Grand Cross of the Red Eagle, 27 January 1869

- Knight of the Prussian Crown, 1st Class, 27 January 1869

- Grand Commander of the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern, with Collar

- Founder of the Ladies Merit Cross, 25 April 1892

- Founder of the Wilhelm-Orden, 18 January 1896

- Founder of the Red Cross Medal, 1 October 1898

- Founder of the Jerusalem Cross, 31 October 1898

- Founder of the Order of Merit of the Prussian Crown, 18 January 1901

- Iron Cross, 1st Class, 1914; Grand Cross, 11 December 1916

- Pour le Mérite (military), 16 February 1915; with Oak Leaves, 12 May 1915

Hohenzollern: Cross of Honour of the Princely House Order of Hohenzollern, 1st Class

Hohenzollern: Cross of Honour of the Princely House Order of Hohenzollern, 1st Class Anhalt:

Anhalt:

- Grand Cross of Albert the Bear, 1884

- Friedrich Cross, 1914

Baden:

Baden:

- Knight of the House Order of Fidelity, 1877

- Knight of the Order of Berthold the First, 28 July 1877

- Grand Cross of the Military Karl-Friedrich Merit Order, 1 November 1914

Bavaria:

Bavaria:

- Knight of St. Hubert, 1881

- Grand Cross of the Military Order of Max Joseph, 1 November 1914

Brunswick:

Brunswick:

- Grand Cross of Henry the Lion, 1881

- War Merit Cross, 1914

Ernestine duchies:

Ernestine duchies:

- Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, 1877

- Cross for Merit in War (Meiningen), 15 October 1917

Free Hanseatic Cities: Hanseatic Crosses, 15 October 1917

Free Hanseatic Cities: Hanseatic Crosses, 15 October 1917 Hesse and by Rhine:

Hesse and by Rhine:

- Knight of the Golden Lion, 9 October 1884

- Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 9 October 1884

Lippe: War Service Cross, 1st Class, 15 October 1917

Lippe: War Service Cross, 1st Class, 15 October 1917 Mecklenburg:

Mecklenburg:

- Grand Cross of the Wendish Crown, with Crown in Ore

- Military Merit Cross, 1st Class (Schwerin), 15 October 1917

Oldenburg:

Oldenburg:

- Grand Cross of the Order of Duke Peter Friedrich Ludwig, with Golden Crown and Collar, 18 February 1878

- Friedrich August Cross, 15 October 1917

Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the White Falcon, 1877

Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the White Falcon, 1877 Saxony:

Saxony:

- Knight of the Rue Crown, 28 July 1877

- Grand Cross of the Military Order of St. Henry, 22 October 1914

Schaumburg-Lippe: Service Cross, 1914

Schaumburg-Lippe: Service Cross, 1914 Württemberg:

Württemberg:

- Grand Cross of the Württemberg Crown, 1877

- Grand Cross of the Military Merit Order, 11 November 1914

- Foreign honours

Austria-Hungary:

Austria-Hungary:

- Grand Cross of St. Stephen, 1872

- Grand Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa, 1914

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold (military), 9 October 1884

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold (military), 9 October 1884 Brazil: Grand Cross of the Southern Cross, 28 July 1877

Brazil: Grand Cross of the Southern Cross, 28 July 1877 Bulgaria:

Bulgaria:

- Grand Cross of St. Alexander, 28 July 1877

- Knight of Saints Cyril and Methodius, with Collar, 1912

- Grand Cross of the Military Merit Order, 18 January 1916

- Order of Bravery, 1st Class, 11 October 1917

Denmark:

Denmark:

- Knight of the Elephant, 28 November 1879

- Cross of Honour of the Order of the Dannebrog, 18 February 1906

Finland: Grand Cross of the Cross of Liberty, with Swords and Diamonds, 30 June 1918

Finland: Grand Cross of the Cross of Liberty, with Swords and Diamonds, 30 June 1918 Greece: Grand Cross of the Redeemer

Greece: Grand Cross of the Redeemer Hawaii: Grand Cross of the Order of Kamehameha I, 1881

Hawaii: Grand Cross of the Order of Kamehameha I, 1881 Italy:

Italy:

- Knight of the Annunciation, 24 September 1873

- Grand Cross of Saints Maurice and Lazarus

- Grand Cross of the Military Order of Savoy, 8 September 1889

Tuscan Grand Ducal Family: Grand Cross of St. Joseph, 9 October 1884

Tuscan Grand Ducal Family: Grand Cross of St. Joseph, 9 October 1884

Sovereign Military Order of Malta: Bailiff Grand Cross of Honour and Devotion

Sovereign Military Order of Malta: Bailiff Grand Cross of Honour and Devotion Japan: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum, 24 September 1886; Collar, 10 December 1894

Japan: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum, 24 September 1886; Collar, 10 December 1894 Korea: Collar of the Order of the Golden Ruler, 9 October 1900

Korea: Collar of the Order of the Golden Ruler, 9 October 1900 Montenegro: Grand Cross of the Order of Prince Danilo I, 28 July 1877

Montenegro: Grand Cross of the Order of Prince Danilo I, 28 July 1877 Netherlands:

Netherlands:

- Grand Cross of the Netherlands Lion, 28 July 1877

- Grand Cross of the Military William Order, 8 September 1889

- Grand Cross of the House Order of Orange, 4 May 1905

Norway:

Norway:

- Grand Cross of St. Olav, with Collar, 1 August 1888

- Knight of the Norwegian Lion, 27 January 1904

Ottoman Empire:

Ottoman Empire:

- Hanedan-i-Ali-Osman, 30 November 1898

- Order of Osmanieh, 1st Class in Diamonds

- Order of Distinction

- Order of Glory in Diamonds, 15 October 1917

- War Service Medal, 15 October 1917

Portugal:

Portugal:

- Grand Cross of the Tower and Sword, 9 October 1884; with Collar, 1888

- Grand Cross of the Sash of the Two Orders

Russia:

Russia:

- Knight of St. Andrew, 1872

- Knight of St. Alexander Nevsky, 1872

- Knight of the White Eagle, 1872

- Knight of St. Anna, 1st Class, 1872

- Knight of St. Stanislaus, 1st Class, 1872

Romania:

Romania:

- Grand Cross of the Star of Romania, 28 July 1877

- Grand Cross of the Crown of Romania, 28 July 1877

- Collar of the Order of Carol I, 1906

San Marino: Grand Cross of San Marino, 9 October 1884

San Marino: Grand Cross of San Marino, 9 October 1884 Serbia:

Serbia:

- Grand Cross of the Cross of Takovo, 28 July 1877

- Grand Cross of the White Eagle

Siam:

Siam:

- Grand Cross of the Crown of Siam, 28 July 1877

- Knight of the Order of the Royal House of Chakri, 15 July 1891

Spain: Knight of the Golden Fleece, 8 November 1875

Spain: Knight of the Golden Fleece, 8 November 1875 Sweden:

Sweden:

- Knight of the Seraphim, 25 April 1878; with Collar, 1 November 1888

- Commander Grand Cross of the Order of Vasa, with Collar, 30 July 1909

United Kingdom:

United Kingdom:

- Stranger Knight of the Garter, 27 January 1877 (expelled in 1915)

- Knight of Justice of St. John, 1888 (expelled in 1915)

- Honorary Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order, 21 November 1899 (expelled in 1915)

- Royal Victorian Chain, 9 November 1902 (expelled in 1915)

Venezuela: Collar of the Order of the Liberator, 4 May 1905

Venezuela: Collar of the Order of the Liberator, 4 May 1905