Jawaharlal Nehru, 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964 was an Indian independence activist and, subsequently, the first Prime Minister of India, as well as a central figure in Indian politics both before and after independence. He emerged as an eminent leader of the Indian independence movement, serving India as Prime Minister from its establishment in 1947 as an independent nation, until his death in 1964. He was also known as Pandit Nehru due to his roots with the Kashmiri Pandit community, while Indian children knew him better as Chacha Nehru (Hindi: Uncle Nehru).

The son of Swarup Rani and Motilal Nehru, a prominent lawyer and nationalist statesman, Nehru was a graduate of Trinity College, Cambridge and the Inner Temple, where he trained to be a barrister. Upon his return to India, he enrolled at the Allahabad High Courtand took an interest in national politics, which eventually replaced his legal practice. A committed nationalist since his teenage years, he became a rising figure in Indian politics during the upheavals of the 1910s. He became the prominent leader of the left-wing factions of the Indian National Congress during the 1920s, and eventually of the entire Congress, with the tacit approval of his mentor, Mahatma Gandhi. As Congress President in 1929, Nehru called for complete independence from the British Raj and instigated the Congress’s decisive shift towards the left.

Nehru and the Congress dominated Indian politics during the 1930s as the country moved towards independence. His idea of a secular nation-state was seemingly validated when the Congress swept the 1937 provincial elections and formed the government in several provinces; on the other hand, the separatist Muslim League fared much poorer. However, these achievements were severely compromised in the aftermath of the Quit India Movement in 1942, which saw the British effectively crush the Congress as a political organisation. Nehru, who had reluctantly heeded Gandhi’s call for immediate independence, for he had desired to support the Allied war effort during World War II, came out of a lengthy prison term to a much altered political landscape. The Muslim League under his old Congress colleague and now opponent, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, had come to dominate Muslim politics in India. Negotiations between Congress and Muslim League for power sharing failed and gave way to the independence and bloody partition of India in 1947.

Nehru was elected by the Congress to assume office as independent India’s first Prime Minister, although the question of leadership had been settled as far back as 1941, when Gandhi acknowledged Nehru as his political heir and successor. As Prime Minister, he set out to realise his vision of India. The Constitution of India was enacted in 1950, after which he embarked on an ambitious program of economic, social and political reforms. Chiefly, he oversaw India’s transition from a colony to a republic, while nurturing a plural, multi-party system. In foreign policy, he took a leading role in the Non-Aligned Movement while projecting India as a regional hegemon in South Asia.

Under Nehru’s leadership, the Congress emerged as a catch-all party, dominating national and state-level politics and winning consecutive elections in 1951, 1957, and 1962. He remained popular with the people of India in spite of political troubles in his final years and failure of leadership during the 1962 Sino-Indian War. In India, his birthday is celebrated as Children’s Day.

Early life and career (1889–1912)

Birth and family background

Jawaharlal Nehru was born on 14 November 1889 in Allahabad in British India. His father, Motilal Nehru (1861–1931), a self-made wealthy barrister who belonged to the Kashmiri Pandit community, served twice as President of the Indian National Congress, in 1919 and 1928. His mother, Swarup Rani Thussu (1868–1938), who came from a well-known Kashmiri Brahmin family settled in Lahore, was Motilal’s second wife, the first having died in childbirth. Jawaharlal was the eldest of three children, two of whom were girls. The elder sister, Vijaya Lakshmi, later became the first female president of the United Nations General Assembly. The youngest sister, Krishna Hutheesing, became a noted writer and authored several books on her brother.

Childhood

Nehru described his childhood as a “sheltered and uneventful one.” He grew up in an atmosphere of privilege at wealthy homes including a palatial estate called the Anand Bhavan. His father had him educated at home by private governesses and tutors. Under the influence Ferdinand T. Brooks’ tutelage, Nehru became interested in science and theosophy.He was subsequently initiated into the Theosophical Society at age thirteen by family friend Annie Besant. However, his interest in theosophy did not prove to be enduring and he left the society shortly after Brooks departed as his tutor. He wrote: “for nearly three years was with me and in many ways he influenced me greatly.”

Nehru’s theosophical interests had induced him to the study of the Buddhist and Hindu scriptures. According to Bal Ram Nanda, these scriptures were Nehru’s “first introduction to the religious and cultural heritage of .… provided Nehru the initial impulse for long intellectual quest which culminated…in The Discovery of India.”

Youth

Nehru became an ardent nationalist during his youth. The Second Boer War and the Russo-Japanese War intensified his feelings. About the latter he wrote, ” Japanese victories stirred up my enthusiasm.… Nationalistic ideas filled my mind.… I mused of Indian freedom and Asiatic freedom from the thraldom of Europe.” Later, when he had begun his institutional schooling in 1905 at Harrow, a leading school in England, he was greatly influenced by G. M. Trevelyan’s Garibaldi books, which he had received as prizes for academic merit. He viewed Garibaldi as a revolutionary hero. He wrote: “Visions of similar deeds in India came before, of gallant fight for freedom and in my mind India and Italy got strangely mixed together.”

Graduation

Nehru went to Trinity College, Cambridge in October 1907 and graduated with an honours degree in natural science in 1910. During this period, he also studied politics, economics, history, and literature with little interest. The writings of Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, John Maynard Keynes, Bertrand Russell, Lowes Dickinson, and Meredith Townsendmoulded much of his political and economic thinking.

After completing his degree in 1910, Nehru moved to London and studied law at Inner temple Inn. During this time, he continued to study the scholars of the Fabian Societyincluding Beatrice Webb. He was called to the Bar in 1912.

Advocate practice

After returning to India in August 1912, Nehru enrolled himself as an advocate of the Allahabad High Court and tried to settle down as a barrister. But, unlike his father, he had very little interest in his profession and did not relish either the practice of law or the company of lawyers: “Decidedly the atmosphere was not intellectually stimulating and a sense of the utter insipidity of life grew upon me.” His involvement in nationalist politics would gradually replace his legal practice in the coming years.

-

The Nehru family c. 1890s

-

Nehru dressed in cadet uniform at Harrow School in England

-

Nehru in khaki uniform as a member of Seva Dal

-

Nehru at the Allahabad High Court

Early struggle for independence (1912–1938)

Britain and return to India: 1912–1913

Nehru had developed an interest in Indian politics during his time in Britain as a student and a barrister.

Within months of his return to India in 1912, Nehru attended an annual session of the Indian National Congress in Patna. Congress in 1912 was the party of moderates and elites, and he was disconcerted by what he saw as “very much an English-knowing upper-class affair.” Nehru harboured doubts regarding the effectiveness of Congress but agreed to work for the party in support of the Indian civil rights movement led by Mahatma Gandhi in South Africa, collecting funds for the movement in 1913. Later, he campaigned against indentured labour and other such discrimination faced by Indians in the British colonies.

World War I: 1914–1915

When World War I broke out, sympathy in India was divided. Although educated Indians “by and large took a vicarious pleasure” in seeing the British rulers humbled, the ruling upper classes sided with the Allies. Nehru confessed that he viewed the war with mixed feelings. As Frank Moraes writes, “f sympathy was with any country it was with France, whose culture he greatly admired.” During the war, Nehru volunteered for the St. John Ambulance and worked as one of the provincial secretaries of the organisation in Allahabad. He also spoke out against the censorship acts passed by the British government in India.

Nehru in 1919 with wife Kamalaand daughter Indira

Nehru emerged from the war years as a leader whose political views were considered radical. Although the political discourse had been dominated at this time by Gopal Krishna Gokhale, a moderate who said that it was “madness to think of independence,” Nehru had spoken “openly of the politics of non-cooperation, of the need of resigning from honorary positions under the government and of not continuing the futile politics of representation.” He ridiculed the Indian Civil Service for its support of British policies. He noted that someone had once defined the Indian Civil Service, “with which we are unfortunately still afflicted in this country, as neither Indian, nor civil, nor a service.” Motilal Nehru, a prominent moderate leader, acknowledged the limits of constitutional agitation, but counselled his son that there was no other “practical alternative” to it. Nehru, however, was not satisfied with the pace of the national movement. He became involved with aggressive nationalists leaders who were demanding Home Rule for Indians.

The influence of the moderates on Congress politics began to wane after Gokhale died in 1915. Anti-moderate leaders such as Annie Besantand Bal Gangadhar Tilak took the opportunity to call for a national movement for Home Rule. However, in 1915, the proposal was rejected because of the reluctance of the moderates to commit to such a radical course of action.

Home rule movement: 1916–1917

Besant nevertheless formed a league for advocating Home Rule in 1916, and Tilak, on his release from a prison term, had in April 1916 formed his own league. Nehru joined both leagues but worked especially for the former. He remarked later that ” had a very powerful influence on me in my childhood…even later when I entered political life her influence continued.” Another development which brought about a radical change in Indian politics was the espousal of Hindu-Muslim unity with the Lucknow Pact at the annual meeting of the Congress in December 1916. The pact had been initiated earlier in the year at Allahabad at a meeting of the All India Congress Committee which was held at the Nehru residence at Anand Bhawan. Nehru welcomed and encouraged the rapprochement between the two Indian communities.

Several nationalist leaders banded together in 1916 under the leadership of Annie Besant to voice a demand for self-governance, and to obtain the status of a Dominion within the British Empire as enjoyed by Australia, Canada, South Africa, New Zealand, and Newfoundland at the time. Nehru joined the movement and rose to become secretary of Besant’s Home Rule League.

In June 1917, Besant was arrested and interned by the British government. The Congress and various other Indian organisations threatened to launch protests if she were not set free. The British government was subsequently forced to release Besant and make significant concessions after a period of intense protest.

Non-cooperation: 1920–1927

The first big national involvement of Nehru came at the onset of the Non-Cooperation movement in 1920. He led the movement in the United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh). Nehru was arrested on charges of anti-governmental activities in 1921, and was released a few months later. In the rift that formed within the Congress following the sudden closure of the Non-Cooperation movement after the Chauri Chaura incident, Nehru remained loyal to Gandhi and did not join the Swaraj Party formed by his father Motilal Nehru and CR Das. In 1923, Nehru suffered imprisonment in Nabha, a princely state, when he went there to see the struggle that was being waged by the Sikhs against the corrupt Mahants.

Internationalising struggle for Indian independence: 1927

Nehru and his daughter Indira in Britain, 1930s

Nehru played a leading role in the development of the internationalist outlook of the Indian independence struggle. He sought foreign allies for India and forged links with movements for independence and democracy all over the world. In 1927, his efforts paid off and the Congress was invited to attend the congress of oppressed nationalities in Brussels in Belgium. The meeting was called to coordinate and plan a common struggle against imperialism. Nehru represented India and was elected to the Executive Council of the League against Imperialism that was born at this meeting.

Increasingly, Nehru saw the struggle for independence from British imperialism as a multinational effort by the various colonies and dominions of the Empire; some of his statements on this matter, however, were interpreted as complicity with the rise of Hitler and his espoused intentions. In the face of these allegations, Nehru responded:

We have sympathy for the national movement of Arabs in Palestine because it is directed against British Imperialism. Our sympathies cannot be weakened by the fact that the national movement coincides with Hitler’s interests.

Fundamental Rights and Economic Policy: 1929

Nehru in a procession at Peshawar, North-West Frontier Province, 14 October 1937

Nehru drafted the policies of the Congress and a future Indian nation in 1929. He declared that the aims of the congress were freedom of religion; right to form associations; freedom of expression of thought; equality before law for every individual without distinction of caste, colour, creed, or religion; protection to regional languages and cultures, safeguarding the interests of the peasants and labour; abolition of untouchability; introduction of adult franchise; imposition of prohibition, nationalisation of industries; socialism; and establishment of a secular India. All these aims formed the core of the “Fundamental Rights and Economic Policy” resolution drafted by Nehru in 1929–1931 and were ratified in 1931 by the Congress party session at Karachi chaired by Vallabhbhai Patel.

Declaration of independence

Nehru was one of the first leaders to demand that the Congress Party should resolve to make a complete and explicit break from all ties with the British Empire. His resolution for independence was approved at the Madras session of Congress in 1927 despite Gandhi’s criticism. At that time he also formed Independence for India league, a pressure group within the Congress. In 1928, Gandhi agreed to Nehru’s demands and proposed a resolution that called for the British to grant dominion status to India within two years. If the British failed to meet the deadline, the Congress would call upon all Indians to fight for complete independence. Nehru was one of the leaders who objected to the time given to the British—he pressed Gandhi to demand immediate actions from the British. Gandhi brokered a further compromise by reducing the time given from two years to one. Nehru agreed to vote for the new resolution.

Demands for dominion status were rejected by the British in 1929. Nehru assumed the presidency of the Congress party during the Lahore session on 29 December 1929 and introduced a successful resolution calling for complete independence. Nehru drafted the Indian declaration of independence, which stated:

We believe that it is the inalienable right of the Indian people, as of any other people, to have freedom and to enjoy the fruits of their toil and have the necessities of life, so that they may have full opportunities of growth. We believe also that if any government deprives a people of these rights and oppresses them the people have a further right to alter it or abolish it. The British government in India has not only deprived the Indian people of their freedom but has based itself on the exploitation of the masses, and has ruined India economically, politically, culturally and spiritually. We believe therefore, that India must sever the British connection and attain Purna Swaraj or complete independence.

At midnight on New Year’s Eve 1929, Nehru hoisted the tricolour flag of India upon the banks of the Ravi in Lahore. A pledge of independence was read out, which included a readiness to withhold taxes. The massive gathering of public attending the ceremony was asked if they agreed with it, and the vast majority of people were witnessed to raise their hands in approval. 172 Indian members of central and provincial legislatures resigned in support of the resolution and in accordance with Indian public sentiment. The Congress asked the people of India to observe 26 January as Independence Day. The flag of India was hoisted publicly across India by Congress volunteers, nationalists and the public. Plans for a mass civil disobedience were also underway.

After the Lahore session of the Congress in 1929, Nehru gradually emerged as the paramount leader of the Indian independence movement. Gandhi stepped back into a more spiritual role. Although Gandhi did not officially designate Nehru his political heir until 1942, the country as early as the mid-1930s saw in Nehru the natural successor to Gandhi.

Salt March: 1930

Nehru and most of the Congress leaders were initially ambivalent about Gandhi’s plan to begin civil disobedience with a satyagraha aimed at the British salt tax. After the protest gathered steam, they realised the power of salt as a symbol. Nehru remarked about the unprecedented popular response, “it seemed as though a spring had been suddenly released.” He was arrested on 14 April 1930 while on train from Allahabad for Raipur. He had earlier, after addressing a huge meeting and leading a vast procession, ceremoniously manufactured some contraband salt. He was charged with breach of the salt law, tried summarily behind prison walls and sentenced to six months of imprisonment.

He nominated Gandhi to succeed him as Congress President during his absence in jail, but Gandhi declined, and Nehru then nominated his father as his successor. With Nehru’s arrest the civil disobedience acquired a new tempo, and arrests, firing on crowds and lathi charges grew to be ordinary occurrences.

Salt satyagraha success

The Salt Satyagraha succeeded in drawing the attention of the world. Indian, British, and world opinion increasingly began to recognise the legitimacy of the claims by the Congress party for independence. Nehru considered the salt satyagraha the high-water mark of his association with Gandhi, and felt that its lasting importance was in changing the attitudes of Indians:

Of course these movements exercised tremendous pressure on the British Government and shook the government machinery. But the real importance, to my mind, lay in the effect they had on our own people, and especially the village masses.… Non-cooperation dragged them out of the mire and gave them self-respect and self-reliance.… They acted courageously and did not submit so easily to unjust oppression; their outlook widened and they began to think a little in terms of India as a whole.… It was a remarkable transformation and the Congress, under Gandhi’s leadership, must have the credit for it.

Electoral politics, Europe, and economics: 1936–1938

Gandhi and Nehru in 1942

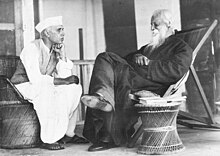

Jawaharlal Nehru and Rabindranath Tagore

During the mid-1930s, Nehru was much concerned with developments in Europe, which seemed to be drifting toward another world war. He was in Europe in early 1936, visiting his ailing wife, shortly before she died in a sanitarium in Switzerland. At that time, he emphasised that, in the event of war, India’s place was alongside the democracies, though he insisted that India could only fight in support of Great Britain and France as a free country.

Nehru’s visit to Europe in 1936 proved to be the watershed in his political and economic thinking. His real interest in Marxism and his socialistpattern of thought stem from that tour. His subsequent sojourns in prison enabled him to study Marxism in more depth. Interested in its ideas but repelled by some of its methods, he could never bring himself to accept Karl Marx’s writings as revealed scripture. Yet from then on, the yardstick of his economic thinking remained Marxist, adjusted, where necessary, to Indian conditions.

At the 1936 Lucknow session of 1936, the Congress party, despite opposition from the newly elected Nehru as the party president, agreed to contest the provincial elections to be held in 1937 under the Government of India Act 1935. The elections brought Congress party to power in a majority of the provinces with increased popularity and power for Nehru. Since the Muslim League under Muhammad Ali Jinnah(who was to become the creator of Pakistan) had fared badly at the polls, Nehru declared that the only two parties that mattered in India were the British colonial authorities and the Congress. Jinnah’s statements that the Muslim League was the third and “equal partner” within Indian politics was widely rejected. Nehru had hoped to elevate Maulana Azad as the preeminent leader of Indian Muslims, but in this, he was undermined by Gandhi, who continued to treat Jinnah as the voice of Indian Muslims.

In the 1930s, the Congress Socialist Party group was formed within the INC under the leadership of Jayaprakash Narayan, Narendra Deo, and others. Nehru, however, never joined the group but did act as bridge between them and Gandhi. He had the support of the left-wing Congressmen Maulana Azad and Subhas Chandra Bose. The trio combined to oust Dr. Prasad as Congress President in 1936. Nehru was elected in his place and held the presidency for two years (1936–37). He was then succeeded by his socialist colleagues Bose (1938–39) and Azad (1940–46). During Nehru’s second term as general secretary of the Congress, he proposed certain resolutions concerning the foreign policy of India. From that time onward, he was given carte blanche in framing the foreign policy of any future Indian nation. Nehru worked closely with Bose in developing good relations with governments of free countries all over the world.

Nehru was one of the first nationalist leaders to realise the sufferings of the people in the states ruled by Indian princes. The nationalist movement had been confined to the territories under direct British rule. He helped to make the struggle of the people in the princely states a part of the nationalist movement for independence. Nehru was also given the responsibility of planning the economy of a future India and appointed the National Planning Commission in 1938 to help in framing such policies. However, many of the plans framed by Nehru and his colleagues would come undone with the unexpected partition of India in 1947.

The All India States Peoples Conference (AISPC) was formed in 1927 and Nehru, who had been supporting the cause of the people of the princely states for many years, was made the President of the organization in 1939.