Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician who was the leader of the Nazi Party, Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and Führer (‘Leader’) of Nazi Germany from 1934 to 1945. He committed suicide by gunshot on 30 April 1945 in his Führerbunker in Berlin. Eva Braun, his wife of one day, committed suicide with him by taking cyanide. In accordance with his prior written and verbal instructions, that afternoon their remains were carried up the stairs through the bunker’s emergency exit, doused in petrol, and set alight in the Reich Chancellery garden outside the bunker.

Although records in the Soviet archives indicate that their burned remains were recovered and interred in successive locations until 1946, and that they were exhumed again and cremated in 1970, and the ashes were scattered, this has been shown to be extremely unlikely to have occurred, since eyewitnesses testified that there were no bodies per se remaining after the burning, just ashes. The suggestion that the bodies were serially exhumed and re-buried is considered to be part of a Soviet disinformation campaign on the order of Joseph Stalin to sow confusion regarding Hitler’s death.

Concerning Hitler’s cause of death, one non-eyewitness account claims that he died by poison only, but all three eyewitnesses who saw Hitler’s body immediately after his suicide testified that he died by a self-inflicted gunshot wound, although two say it was a shot to the temple, and one says that it was into the mouth. Otto Günsche, Hitler’s personal adjutant, who handled both bodies, testified that while Braun’s smelled strongly of burnt almonds – an indication of cyanide poisoning – there was no such odour about Hitler’s body, which smelled of gunpowder. Dental remains sifted from the soil in the garden were matched with his dental records in 1945. Contemporary historians have rejected alternate accounts as being either Soviet propaganda or an attempted compromise in order to reconcile the slightly different descriptions of eyewitnesses.

The news of Hitler’s death was announced to Germany on 1 May 1945, the day after its occurrence. For political reasons, the Soviet Union presented various conspiracy theories about Hitler’s death. They maintained in the years immediately following the war that he was not dead, but had fled and was being shielded by the former Western Allies.

Preceding events

By early 1945, Nazi Germany was on the verge of total military collapse. Poland had fallen to the advancing Soviet Red Army, which was preparing to cross the Oder between Küstrin and Frankfurt-an-der-Oder with the objective of capturing Berlin 82 kilometres (51 mi) to the west. German forces had recently lost to the Allies in the Ardennes Offensive, with British and Canadian forces crossing the Rhine into the German industrial heartland of the Ruhr. U.S. forces in the south had captured Lorraine and were advancing towards Mainz, Mannheim, and the Rhine. German forces in Italy were withdrawing north, as they were pressed by the U.S. and Commonwealth forces as part of the Spring Offensive to advance across the Po and into the foothills of the Alps.

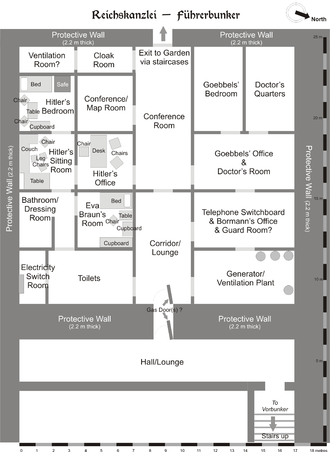

Schematic diagram of the Führerbunker

Hitler retreated to his Führerbunker in Berlin on 16 January 1945. It was clear to the Nazi leadership that the battle for Berlin would be the final battle of the war in Europe. Some 325,000 soldiers of Germany’s Army Group B were surrounded and captured in the Ruhr Pocket on 18 April, leaving the path open for U.S. forces to reach Berlin. By 11 April the Americans crossed the Elbe, 100 kilometres (62 mi) to the west of the city. On 16 April, Soviet forces to the east crossed the Oder and commenced the battle for the Seelow Heights, the last major defensive line protecting Berlin on that side. By 19 April, the Germans were in full retreat from Seelow Heights, leaving no front line. Berlin was bombarded by Soviet artillery for the first time on 20 April, which was also Hitler’s birthday. By the evening of 21 April, Red Army tanks reached the outskirts of the city.

At the afternoon situation conference on 22 April, Hitler suffered a total nervous collapse when he was informed that the orders he had issued the previous day for SS-General Felix Steiner’s Army Detachment Steiner to counterattack had not been obeyed. Hitler launched a tirade against his commanders, calling them treacherous and incompetent, culminating in a declaration—for the first time—that the war was lost. Hitler announced that he would stay in Berlin until the end and then shoot himself. Later that day, he asked SS physician Werner Haase about the most reliable method of suicide. Haase suggested the “pistol-and-poison method” of combining a dose of cyanide with a gunshot to the head. Luftwaffe chief Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring learned about this and sent a telegram to Hitler asking for permission to take over the leadership of the Reich in accordance with Hitler’s 1941 decree naming him as his successor. Hitler’s secretary Martin Bormann convinced Hitler that Göring was threatening a coup. In response, Hitler informed Göring that he would be executed unless he resigned all of his posts. Later that day, he sacked Göring from all of his offices and ordered his arrest.

By 27 April, Berlin was cut off from the rest of Germany. Secure radio communications with defending units had been lost; the command staff in the Führerbunker had to depend on telephone lines for passing instructions and orders, and on public radio for news and information. On 28 April, Hitler received a BBC report originating from Reuters; the report stated that Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler had offered to surrender to the Western Allies. The offer was declined. Himmler had implied to the Allies that he had the authority to negotiate a surrender, which Hitler considered to be treason. That afternoon, Hitler’s anger and bitterness escalated into a rage against Himmler. Hitler ordered Himmler’s arrest and had Hermann Fegelein (Himmler’s SS representative at Hitler’s headquarters) shot for desertion.

By this time, the Red Army had advanced to the Potsdamer Platz, and all indications were that they were preparing to storm the Chancellery. This report and Himmler’s treachery prompted Hitler to make the last decisions of his life. Shortly after midnight on 29 April, he married Eva Braun in a small civil ceremony in a map room within the Führerbunker. The two then hosted a modest wedding breakfast, after which Hitler took secretary Traudl Junge to another room and dictated his last will and testament. It left instructions to be carried out immediately following his death, with Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz and Joseph Goebbels assuming Hitler’s roles as head of state and chancellor respectively. Hitler signed these documents at 04:00 and then went to bed. Some sources say that he dictated the last will and testament immediately before the wedding, but all agree on the timing of the signing.

Eva Braun and Hitler (with Blondi), June 1942

On the afternoon of 29 April, Hitler learned that his ally, Benito Mussolini, had been executed by Italian partisans. The bodies of Mussolini and his mistress, Clara Petacci, had been strung up by their heels. The corpses were later cut down and thrown into the gutter, where they were mocked by Italian dissenters. These events may have strengthened Hitler’s resolve not to allow himself or his wife to be made a “spectacle” of, as he had earlier recorded in his testament. Hitler had been given some capsules of prussic acid by Heinrich Himmler through SS physician Dr Ludwig Stumpfegger, and initially had intended to use them for his suicide. But when he received the news that Himmler had contacted the Western Allies through a Swedish diplomat to arrange for an end to the war, Hitler was outraged. With this betrayal in his mind, Hitler began to doubt whether the ampoules would be effective. He ordered Dr Haase to test one on his dog Blondi. The capsule worked – the dog died instantly.

Suicide

Hitler and Braun lived together as husband and wife in the bunker for less than forty hours. By 01:00 on 30 April, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel had reported that all of the forces on which Hitler had been depending to rescue Berlin had either been encircled or forced onto the defensive. At around 02:30, Hitler appeared in the corridor where about twenty people, mostly women, were assembled to give their farewells. He went down the line, shaking hands and speaking with each of them, before retiring to his quarters. Late in the morning, with the Soviets less than 500 metres (1,600 ft) from the Führerbunker, Hitler had a meeting with General Helmuth Weidling, the commander of the Berlin Defence Area. Weidling told Hitler that the garrison would probably run out of ammunition that night, and that the fighting in Berlin would inevitably come to an end within the next 24 hours. Weidling asked for permission for a break-out; this was a request he had unsuccessfully made before. Hitler did not answer, and Weidling went back to his headquarters in the Bendlerblock. At about 13:00 he received Hitler’s permission to try a break-out that night. Hitler, two secretaries, and his personal cook then had lunch, after which Hitler and Braun said goodbye to members of the bunker staff and fellow occupants, including Bormann, Goebbels, the secretaries, and several military officers. At around 14:30 Adolf and Eva Hitler went into his personal study. Hitler’s adjutant, SS-Sturmbannführer Otto Günsche stood guard outside the study door.

Situation of World War II in Europe at the time of Hitler’s death. The white areas were controlled by Nazi forces, the pink areas were controlled by the Allies, and the red areas indicate recent Allied advances.

After some time, Heinz Linge, Hitler’s valet, opened the study door. Linge later stated that he immediately noted a scent of burnt almonds, which is a common observation in the presence of hydrogen cyanide. Linge saw the bodies of Hitler and Braun sitting on the sofa, with Hitler to Braun’s right. His head was canted to his right. Günsche entered the study shortly afterwards. He described Braun’s corpse as being on Hitler’s left, with her legs drawn up and slumped away from him. Günsche stated that Hitler “sat … sunken over, with blood dripping out of his right temple. He had shot himself with his own pistol, a Walther PPK 7.65.” The gun lay at his feet. Hitler’s dripping blood had made a large stain on the right arm of the sofa and was pooling on the carpet. According to Linge, Eva Braun’s body had no visible wounds, and her face showed how she had died – by cyanide poisoning. Günsche and SS-Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke stated “unequivocally” that all outsiders and those performing duties and work in the bunker “did not have any access” to Hitler’s private living quarters during the time of death (between 15:00 and 16:00).

Günsche left the study and announced that Hitler was dead. Linge, Günsche, Hitler Youth leader Artur Axmann and others viewed the bodies. Linge and another man rolled up Hitler’s body in a rug, and then, in accordance with Hitler’s prior written and verbal instructions, his and Braun’s bodies were carried up the stairs and through the bunker’s emergency exit to the garden behind the Reich Chancellery, where they were to be burned with petrol. Although Hitler’s corpse was partially covered by the rug, numerous witnesses testified to recognising him, as the top of his head was not covered, nor were his lower legs and feet.

The bunker telephone operator SS-Oberscharführer Rochus Misch reported Hitler’s death to Führerbegleitkommando (Führer Escort Command) chief Franz Schädle and returned to the switchboard, later recalling someone shouting that Hitler’s body was being burned. After the first attempts to ignite the petrol did not work, Linge went back inside the bunker and returned with a thick roll of papers. Bormann lit the papers and threw them onto the bodies. As the two corpses caught fire, a group including Bormann, Günsche, Linge, Goebbels, Erich Kempka, Peter Högl, Ewald Lindloff, and Hans Reisser raised their arms in salute as they stood just inside the bunker doorway.

At around 16:15, Linge ordered SS-Untersturmführer Heinz Krüger and SS-Oberscharführer Werner Schwiedel to roll up the rug in Hitler’s study to burn it. Schwiedel later stated that upon entering the study, he saw a pool of blood the size of a “large dinner plate” by the arm-rest of the sofa. Noticing a spent cartridge case, he bent down and picked it up from where it lay on the rug about 1 mm from a 7.65 pistol. The two men removed the blood-stained rug and carried it up the stairs and outside to the Chancellery garden, where it was placed on the ground and burned.

The Red Army shelled the area in and around the Reich Chancellery on and off during the afternoon. SS guards brought over additional cans of petrol to further burn the corpses. Linge later noted that this fire did not completely destroy the remains, as the corpses were being burned in the open, where the distribution of heat varies, as opposed to a crematorium where the heat is all focused on the burning body. The corpses burned from 16:00 to 18:30. At approximately 18:30, Lindloff and Reisser covered up the by then ashen remains in a shallow bomb crater. The shelling and a fire from napalm incendiary bombs continued until 2 May. During this period it was difficult to spend any time in the garden because of the continuous shelling.

Aftermath

The first inkling to the outside world that Hitler was dead came from the Germans themselves. On 1 May, the Reichssender Hamburg radio station interrupted their normal program to announce that Hitler had died that afternoon, and introduced his successor, President Karl Dönitz. Dönitz called upon the German people to mourn their Führer, who he stated had died a hero defending the capital of the Reich. Hoping to save the army and the nation by negotiating a partial surrender to the British and Americans, Dönitz authorised a fighting withdrawal to the west. His tactic was somewhat successful: it enabled about 1.8 million German soldiers to avoid capture by the Soviets, but it came at a high cost in bloodshed, as troops continued to fight until 8 May.

General Hans Krebs met Soviet General Vasily Chuikov just prior to 04:00 on 1 May, giving him the news of Hitler’s death, while attempting to negotiate a ceasefire and open “peace negotiations”. Joseph Stalin was informed of Hitler’s suicide around 04:05 Berlin time, thirteen hours after the event. He demanded unconditional surrender, which Krebs lacked authorisation to give. Stalin wanted confirmation that Hitler was dead and ordered the Red Army’s SMERSH unit to find the corpse. In the early morning hours of 2 May, the Soviets captured the Reich Chancellery. Inside the Führerbunker, General Krebs and General Wilhelm Burgdorf committed suicide by gunshot to the head.

On 4 May, dental remains, including bridges later identified by the dental assistant and dental technician who had worked on them as a match with Hitler’s and Braun’s, were sifted from the soil. These remains, along with those of two dogs (thought to be Blondi and her offspring, Wulf), were removed the next day and secretly delivered to the SMERSH Counter-Espionage Section of the 3rd Assault Army in Buch. Stalin was wary of believing Hitler was dead, and restricted the release of information to the public. By 11 May, his dentist’s assistant Käthe Heusermann and dental technician Fritz Echtmann both confirmed dental remains of Hitler and Braun. Details of an alleged Soviet autopsy of Hitler were made public in 1968 and used by forensic odontologists Reidar F. Sognnaes and Ferdinand Strøm to declare the dental remains as Hitler’s in 1972.

In early June 1945, the remains of Joseph and Magda Goebbels, the Goebbels children, Krebs, Blondi and another dog were moved from Buch to Finow. Hitler and Braun’s remains were alleged to have been moved as well, but this is most likely Soviet disinformation. There is no evidence that any actual bodily remains of Hitler or Braun – with the exception of the dental bridges – were found by the Soviets. The remains of the Goebbels family and the dogs were reburied in a forest in Brandenburg on 3 June, and finally exhumed and moved to the SMERSH unit’s new facility in Magdeburg, where they were buried in five wooden boxes on 21 February 1946. By 1970, the facility was under the control of the KGB and scheduled to be relinquished to East Germany. Concerned that a known Nazi burial site might become a neo-Nazi shrine, KGB director Yuri Andropov authorised an operation to destroy the remains that were buried there in 1946. A KGB team was given detailed burial charts and on 4 April 1970 secretly exhumed the remains of ten or eleven bodies “in an advanced state of decay”. The remains were thoroughly burned and crushed, and the ashes thrown into the Biederitz river, a tributary of the nearby Elbe.

For politically motivated reasons, the Soviet Union presented various versions of Hitler’s fate. When asked in July 1945 how Hitler had died, Stalin said he was living “in Spain or Argentina”. In November 1945, Dick White, the head of counter-intelligence in the British sector of Berlin, had their agent Hugh Trevor-Roper investigate the matter to counter the Soviet claims. His report was expanded and published in 1947 as The Last Days of Hitler. In the years immediately after the war, the Soviets maintained that Hitler was not dead, but had escaped and was being shielded by the former Western Allies, was in Francoist Spain, or was somewhere in South America. Conspiracy theories about his death and about the Nazi era as a whole continue to attract interest.

Throughout the late 1940s and 1950s, the FBI and CIA received many leads claiming that Hitler might still be alive, while giving none of them credence. The documents were declassified under the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act, and began to be released online by the early 2010s. The secrecy in which the investigation was shrouded has inspired a number of conspiracy theories.

Further Soviet investigations and disinformation

At the end of 1945, Stalin ordered the NKVD to form a second commission to investigate Hitler’s death. Blood samples from the sofa and wall were taken to confirm that it matched Hitler’s blood type (type A). On 30 May 1946, MVD agents were reported to have recovered two fragments of a skull from the crater where Hitler was buried. The left parietal bone had gunshot damage. This piece remained uncatalogued until 1975, and was rediscovered in the Russian State Archives in 1993. In 2009, DNA and forensic tests were performed on a small piece detached from the skull fragment, which Soviet officials had long believed to be Hitler’s. According to the U.S. researchers, their tests revealed that it actually belonged to a woman and the examination of the skull sutures placed her at less than 40 years old. The same researchers also DNA-tested a fragment of cloth from the sofa soaked with Hitler’s blood, and confirmed that it belonged to a male. French forensic pathologist Philippe Charlier later explained, “When doing a diagnostic of the skull, you have a 55 per cent chance of getting the sex right.”

On 29 December 1949, a secret dossier was presented to Stalin, which was based upon the thorough questioning of Nazis who had been present in the Führerbunker, including Günsche and Linge. Western historians were allowed into the archives of the former Soviet Union beginning in 1991, but the dossier remained undiscovered for twelve years; in 2005 it was published as The Hitler Book.

In 1968, Soviet journalist Lev Bezymenski published his book, The Death of Adolf Hitler. He describes a purported Soviet forensic examination led by Faust Shkaravsky, which concluded that Hitler had died by cyanide poisoning, while Bezymenski theorises that Hitler requested a coup de grâce to ensure his quick death. Bezymenski later admitted that his work included “deliberate lies”, such as the manner of Hitler’s death. Anton Joachimsthaler, in his extensive investigation of the circumstances surrounding Hitler’s death, quotes a German pathologist as saying about the autopsy described in Bezymenski’s book: “Bezemensky’s report is ridiculous. … Any one of my assistants would have done better … the whole thing is a farce … it is intolerably bad work … the transcript of the post-mortem section of 8 1945 describes anything but Hitler.”

Gallery

-

Joseph Goebbels, his wife Magda, and their six children. Edited into the photo in the back is Goebbels’ stepson, Harald Quandt, who was the sole family member to survive the war.

-

Hitler (right) visiting Berlin defenders in early April 1945 with Hermann Göring (centre) and the Chief of the OKW Field Marshal Keitel (partially hidden)

-

Heinz Linge, Hitler’s valet, was one of the first people into Hitler’s study after the suicide.

-

Churchill sits on a damaged chair from the Führerbunker in July 1945.