A city is a large human settlement. It can be defined as a permanent and densely settled place with administratively defined boundaries whose members work primarily on non-agricultural tasks. Cities generally have extensive systems for housing, transportation, sanitation, utilities, land use, production of goods, and communication. Their density facilitates interaction between people, government organisations and businesses, sometimes benefiting different parties in the process, such as improving efficiency of goods and service distribution.

Historically, city-dwellers have been a small proportion of humanity overall, but following two centuries of unprecedented and rapid urbanization, more than half of the world population now lives in cities, which has had profound consequences for global sustainability. Present-day cities usually form the core of larger metropolitan areas and urban areas—creating numerous commuters traveling towards city centres for employment, entertainment, and edification. However, in a world of intensifying globalisation, all cities are to varying degrees also connected globally beyond these regions. This increased influence means that cities also have significant influences on global issues, such as sustainable development, global warming and global health. Because of these major influences on global issues, the international community has prioritized investment in sustainable cities through Sustainable Development Goal 11. Due to the efficiency of transportation and the smaller land consumption, dense cities hold the potential to have a smaller ecological footprint per inhabitant than more sparsely populated areas. Therefore, compact cities are often referred to as a crucial element of fighting climate change. However, this concentration can also have significant negative consequences, such as forming urban heat islands, concentrating pollution, and stressing water supplies and other resources.

Other important traits of cities besides population include the capital status and relative continued occupation of the city. For example, country capitals such as Beijing, London, Mexico City, Moscow, Nairobi, New Delhi, Paris, Rome, Athens, Seoul, Tokyo, and Washington, D.C. reflect the identity and apex of their respective nations. Some historic capitals, such as Kyoto, maintain their reflection of cultural identity even without modern capital status. Religious holy sites offer another example of capital status within a religion, Jerusalem, Mecca, Varanasi, Ayodhya, Haridwar and Prayagraj each hold significance. The cities of Jericho, Faiyum, Damascus, Athens, Aleppo and Argos are among those laying claim to the longest continual inhabitation.

Meaning

Palitana represents the city’s symbolic function in the extreme, devoted as it is to Jain temples.

A city is distinguished from other human settlements by its relatively great size, but also by its functions and its special symbolic status, which may be conferred by a central authority. The term can also refer either to the physical streets and buildings of the city or to the collection of people who dwell there, and can be used in a general sense to mean urban rather than rural territory.

National censuses use a variety of definitions – invoking factors such as population, population density, number of dwellings, economic function, and infrastructure – to classify populations as urban. Typical working definitions for small-city populations start at around 100,000 people. Common population definitions for an urban area (city or town) range between 1,500 and 50,000 people, with most U.S. states using a minimum between 1,500 and 5,000 inhabitants. Some jurisdictions set no such minima. In the United Kingdom, city status is awarded by the Crown and then remains permanently. (Historically, the qualifying factor was the presence of a cathedral, resulting in some very small cities such as Wells, with a population 12,000 as of 2018 and St Davids, with a population of 1,841 as of 2011.) According to the “functional definition” a city is not distinguished by size alone, but also by the role it plays within a larger political context. Cities serve as administrative, commercial, religious, and cultural hubs for their larger surrounding areas. An example of a settlement with “city” in their names which may not meet any of the traditional criteria to be named such include Broad Top City, Pennsylvania (population 452).

The presence of a literate elite is sometimes included in the definition. A typical city has professional administrators, regulations, and some form of taxation (food and other necessities or means to trade for them) to support the government workers. (This arrangement contrasts with the more typically horizontal relationships in a tribe or village accomplishing common goals through informal agreements between neighbors, or through leadership of a chief.) The governments may be based on heredity, religion, military power, work systems such as canal-building, food-distribution, land-ownership, agriculture, commerce, manufacturing, finance, or a combination of these. Societies that live in cities are often called civilizations.

Etymology

The word city and the related civilization come from the Latin root civitas, originally meaning ‘citizenship’ or ‘community member’ and eventually coming to correspond with urbs, meaning ‘city’ in a more physical sense. The Roman civitas was closely linked with the Greek polis—another common root appearing in English words such as metropolis.

In toponymic terminology, names of individual cities and towns are called astionyms (from Ancient Greek ἄστυ ‘city or town’ and ὄνομα ‘name’).

Geography

Hillside housing and graveyard in Kabul

Urban geography deals both with cities in their larger context and with their internal structure.

Site

Downtown Pittsburgh sits at the confluence of the Monongahela and Allegheny rivers, which become the Ohio.

Town siting has varied through history according to natural, technological, economic, and military contexts. Access to water has long been a major factor in city placement and growth, and despite exceptions enabled by the advent of rail transport in the nineteenth century, through the present most of the world’s urban population lives near the coast or on a river.

Urban areas as a rule cannot produce their own food and therefore must develop some relationship with a hinterland which sustains them. Only in special cases such as mining towns which play a vital role in long-distance trade, are cities disconnected from the countryside which feeds them. Thus, centrality within a productive region influences siting, as economic forces would in theory favor the creation of market places in optimal mutually reachable locations.

Center

Kluuvi, a city centre of Helsinki, Finland

The vast majority of cities have a central area containing buildings with special economic, political, and religious significance. Archaeologists refer to this area by the Greek term temenos or if fortified as a citadel. These spaces historically reflect and amplify the city’s centrality and importance to its wider sphere of influence. Today cities have a city center or downtown, sometimes coincident with a central business district.

Public space

Cities typically have public spaces where anyone can go. These include privately owned spaces open to the public as well as forms of public land such as public domain and the commons. Western philosophy since the time of the Greek agora has considered physical public space as the substrate of the symbolic public sphere. Public art adorns (or disfigures) public spaces. Parks and other natural sites within cities provide residents with relief from the hardness and regularity of typical built environments.

Internal structure

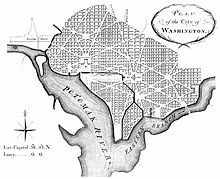

The L’Enfant Plan for Washington, D.C., inspired by the design of Versailles, combines a utilitarian grid pattern with diagonal avenues and a symbolic focus on monumental architecture.

Urban structure generally follows one or more basic patterns: geomorphic, radial, concentric, rectilinear, and curvilinear. Physical environment generally constrains the form in which a city is built. If located on a mountainside, urban structure may rely on terraces and winding roads. It may be adapted to its means of subsistence (e.g. agriculture or fishing). And it may be set up for optimal defense given the surrounding landscape. Beyond these “geomorphic” features, cities can develop internal patterns, due to natural growth or to city planning.

In a radial structure, main roads converge on a central point. This form could evolve from successive growth over a long time, with concentric traces of town walls and citadels marking older city boundaries. In more recent history, such forms were supplemented by ring roads moving traffic around the outskirts of a town. Dutch cities such as Amsterdam and Haarlem are structured as a central square surrounded by concentric canals marking every expansion. In cities such as Moscow, this pattern is still clearly visible.

A system of rectilinear city streets and land plots, known as the grid plan, has been used for millennia in Asia, Europe, and the Americas. The Indus Valley Civilisation built Mohenjo-Daro, Harappa and other cities on a grid pattern, using ancient principles described by Kautilya, and aligned with the compass points. The ancient Greek city of Priene exemplifies a grid plan with specialized districts used across the Hellenistic Mediterranean.

Urban areas

This aerial view of the Gush Dan metropolitan area in Israel shows the geometrically planned city of Tel Aviv proper (upper left) as well as Givatayim to the east and some of Bat Yam to the south. Tel Aviv’s population is 433,000; the total population of its metropolitan area is 3,785,000.

Urban-type settlement extends far beyond the traditional boundaries of the city proper in a form of development sometimes described critically as urban sprawl. Decentralization and dispersal of city functions (commercial, industrial, residential, cultural, political) has transformed the very meaning of the term and has challenged geographers seeking to classify territories according to an urban-rural binary.

Metropolitan areas include suburbs and exurbs organized around the needs of commuters, and sometimes edge cities characterized by a degree of economic and political independence. (In the US these are grouped into metropolitan statistical areas for purposes of demography and marketing.) Some cities are now part of a continuous urban landscape called urban agglomeration, conurbation, or megalopolis (exemplified by the BosWash corridor of the Northeastern United States.)

History

An arch from the ancient Sumerian city Ur, which flourished in the third millennium BC, can be seen at present-day Tell el-Mukayyar in Iraq

Mohenjo-daro, a city of the Indus Valley Civilization in Pakistan, which was rebuilt six or more times, using bricks of standard size, and adhering to the same grid layout—also in the third millennium BC.

This aerial view of what was once downtown Teotihuacan shows the Pyramid of the Sun, Pyramid of the Moon, and the processional avenue serving as the spine of the city’s street system.

Cities, characterized by population density, symbolic function, and urban planning, have existed for thousands of years. In the conventional view, civilization and the city both followed from the development of agriculture, which enabled production of surplus food, and thus a social division of labour (with concomitant social stratification) and trade. Early cities often featured granaries, sometimes within a temple. A minority viewpoint considers that cities may have arisen without agriculture, due to alternative means of subsistence (fishing), to use as communal seasonal shelters, to their value as bases for defensive and offensive military organization, or to their inherent economic function. Cities played a crucial role in the establishment of political power over an area, and ancient leaders such as Alexander the Great founded and created them with zeal.

Ancient times

Jericho and Çatalhöyük, dated to the eighth millennium BC, are among the earliest proto-cities known to archaeologists.

In the fourth and third millennium BC, complex civilizations flourished in the river valleys of Mesopotamia, India, China, and Egypt. Excavations in these areas have found the ruins of cities geared variously towards trade, politics, or religion. Some had large, dense populations, but others carried out urban activities in the realms of politics or religion without having large associated populations. Among the early Old World cities, Mohenjo-daro of the Indus Valley Civilization in present-day Pakistan, existing from about 2600 BC, was one of the largest, with a population of 50,000 or more and a sophisticated sanitation system. China’s planned cities were constructed according to sacred principles to act as celestial microcosms. The Ancient Egyptian cities known physically by archaeologists are not extensive. They include (known by their Arab names) El Lahun, a workers’ town associated with the pyramid of Senusret II, and the religious city Amarna built by Akhenaten and abandoned. These sites appear planned in a highly regimented and stratified fashion, with a minimalistic grid of rooms for the workers and increasingly more elaborate housing available for higher classes.

In Mesopotamia, the civilization of Sumer, followed by Assyria and Babylon, gave rise to numerous cities, governed by kings and fostering multiple languages written in cuneiform. The Phoenician trading empire, flourishing around the turn of the first millennium BC, encompassed numerous cities extending from Tyre, Cydon, and Byblos to Carthage and Cádiz.

In the following centuries, independent city-states of Greece, especially Athens, developed the polis, an association of male landowning citizens who collectively constituted the city. The agora, meaning “gathering place” or “assembly”, was the center of athletic, artistic, spiritual and political life of the polis. Rome was the first city that surpassed one million inhabitants. Under the authority of its empire, Rome transformed and founded many cities (coloniae), and with them brought its principles of urban architecture, design, and society.

In the ancient Americas, early urban traditions developed in the Andes and Mesoamerica. In the Andes, the first urban centers developed in the Norte Chico civilization, Chavin and Moche cultures, followed by major cities in the Huari, Chimu and Inca cultures. The Norte Chico civilization included as many as 30 major population centers in what is now the Norte Chico region of north-central coastal Peru. It is the oldest known civilization in the Americas, flourishing between the 30th century BC and the 18th century BC. Mesoamerica saw the rise of early urbanism in several cultural regions, beginning with the Olmec and spreading to the Preclassic Maya, the Zapotec of Oaxaca, and Teotihuacan in central Mexico. Later cultures such as the Aztec, Andean civilization, Mayan, Mississippians, and Pueblo peoples drew on these earlier urban traditions. Many of their ancient cities continue to be inhabited, including major metropolitan cities such as Mexico City, in the same location as Tenochtitlan; while ancient continuously inhabited Pueblos are near modern urban areas in New Mexico, such as Acoma Pueblo near the Albuquerque metropolitan area and Taos Pueblo near Taos; while others like Lima are located nearby ancient Peruvian sites such as Pachacamac.

Jenné-Jeno, located in present-day Mali and dating to the third century BC, lacked monumental architecture and a distinctive elite social class—but nevertheless had specialized production and relations with a hinterland. Pre-Arabic trade contacts probably existed between Jenné-Jeno and North Africa. Other early urban centers in sub-Saharan Africa, dated to around 500 AD, include Awdaghust, Kumbi-Saleh the ancient capital of Ghana, and Maranda a center located on a trade route between Egypt and Gao.

Middle Ages

Vyborg in Leningrad Oblast, Russia has existed since the 13th century

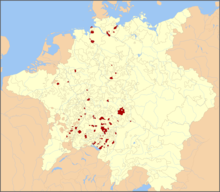

Imperial Free Cities in the Holy Roman Empire 1648

This map of Haarlem, the Netherlands, created around 1550, shows the city completely surrounded by a city wall and defensive canal, with its square shape inspired by Jerusalem.

In the remnants of the Roman Empire, cities of late antiquity gained independence but soon lost population and importance. The locus of power in the West shifted to Constantinople and to the ascendant Islamic civilization with its major cities Baghdad, Cairo, and Córdoba. From the 9th through the end of the 12th century, Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, was the largest and wealthiest city in Europe, with a population approaching 1 million. The Ottoman Empire gradually gained control over many cities in the Mediterranean area, including Constantinople in 1453.

In the Holy Roman Empire, beginning in the 12th. century, free imperial cities such as Nuremberg, Strasbourg, Frankfurt, Basel, Zurich, Nijmegen became a privileged elite among towns having won self-governance from their local lay or secular lord or having been granted self-governanace by the emperor and being placed under his immediate protection. By 1480, these cities, as far as still part of the empire, became part of the Imperial Estates governing the empire with the emperor through the Imperial Diet.

By the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, some cities become powerful states, taking surrounding areas under their control or establishing extensive maritime empires. In Italy medieval communes developed into city-states including the Republic of Venice and the Republic of Genoa. In Northern Europe, cities including Lübeck and Bruges formed the Hanseatic League for collective defense and commerce. Their power was later challenged and eclipsed by the Dutch commercial cities of Ghent, Ypres, and Amsterdam. Similar phenomena existed elsewhere, as in the case of Sakai, which enjoyed a considerable autonomy in late medieval Japan.

In the first millennium AD, the Khmer capital of Angkor in Cambodia grew into the most extensive preindustrial settlement in the world by area, covering over 1,000 sq km and possibly supporting up to one million people.

Early modern

In the West, nation-states became the dominant unit of political organization following the Peace of Westphalia in the seventeenth century. Western Europe’s larger capitals (London and Paris) benefited from the growth of commerce following the emergence of an Atlantic trade. However, most towns remained small.

During the Spanish colonization of the Americas the old Roman city concept was extensively used. Cities were founded in the middle of the newly conquered territories, and were bound to several laws regarding administration, finances and urbanism.

Industrial age

The industrial-based city of Tampere on the shores of the Tammerkoski rapids in 1837.

The growth of modern industry from the late 18th century onward led to massive urbanization and the rise of new great cities, first in Europe and then in other regions, as new opportunities brought huge numbers of migrants from rural communities into urban areas.

Diorama of old Gyumri, Armenia with the Holy Saviour’s Church (1859–1873)

Small city Gyöngyös in Hungary in 1938.

England led the way as London became the capital of a world empire and cities across the country grew in locations strategic for manufacturing. In the United States from 1860 to 1910, the introduction of railroads reduced transportation costs, and large manufacturing centers began to emerge, fueling migration from rural to city areas.

Industrialized cities became deadly places to live, due to health problems resulting from overcrowding, occupational hazards of industry, contaminated water and air, poor sanitation, and communicable diseases such as typhoid and cholera. Factories and slums emerged as regular features of the urban landscape.

Post-industrial age

In the second half of the twentieth century, deindustrialization (or “economic restructuring”) in the West led to poverty, homelessness, and urban decay in formerly prosperous cities. America’s “Steel Belt” became a “Rust Belt” and cities such as Detroit, Michigan, and Gary, Indiana began to shrink, contrary to the global trend of massive urban expansion. Such cities have shifted with varying success into the service economy and public-private partnerships, with concomitant gentrification, uneven revitalization efforts, and selective cultural development. Under the Great Leap Forward and subsequent five-year plans continuing today, the People’s Republic of China has undergone concomitant urbanization and industrialization and to become the world’s leading manufacturer.

Amidst these economic changes, high technology and instantaneous telecommunication enable select cities to become centers of the knowledge economy. A new smart city paradigm, supported by institutions such as the RAND Corporation and IBM, is bringing computerized surveillance, data analysis, and governance to bear on cities and city-dwellers. Some companies are building brand new masterplanned cities from scratch on greenfield sites.

Urbanization

Urbanization is the process of migration from rural into urban areas, driven by various political, economic, and cultural factors. Until the 18th century, an equilibrium existed between the rural agricultural population and towns featuring markets and small-scale manufacturing. With the agricultural and industrial revolutions urban population began its unprecedented growth, both through migration and through demographic expansion. In England the proportion of the population living in cities jumped from 17% in 1801 to 72% in 1891. In 1900, 15% of the world population lived in cities. The cultural appeal of cities also plays a role in attracting residents.

Urbanization rapidly spread across the Europe and the Americas and since the 1950s has taken hold in Asia and Africa as well. The Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, reported in 2014 that for the first time more than half of the world population lives in cities.

Graph showing urbanization from 1950 projected to 2050.

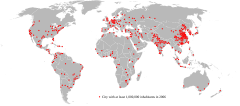

Latin America is the most urban continent, with four fifths of its population living in cities, including one fifth of the population said to live in shantytowns (favelas, poblaciones callampas, etc.). Batam, Indonesia, Mogadishu, Somalia, Xiamen, China and Niamey, Niger, are considered among the world’s fastest-growing cities, with annual growth rates of 5–8%. In general, the more developed countries of the “Global North” remain more urbanized than the less developed countries of the “Global South”—but the difference continues to shrink because urbanization is happening faster in the latter group. Asia is home to by far the greatest absolute number of city-dwellers: over two billion and counting. The UN predicts an additional 2.5 billion citydwellers (and 300 million fewer countrydwellers) worldwide by 2050, with 90% of urban population expansion occurring in Asia and Africa.

Map showing urban areas with at least one million inhabitants in 2006.

Megacities, cities with population in the multi-millions, have proliferated into the dozens, arising especially in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Economic globalization fuels the growth of these cities, as new torrents of foreign capital arrange for rapid industrialization, as well as relocation of major businesses from Europe and North America, attracting immigrants from near and far. A deep gulf divides rich and poor in these cities, with usually contain a super-wealthy elite living in gated communities and large masses of people living in substandard housing with inadequate infrastructure and otherwise poor conditions.

Cities around the world have expanded physically as they grow in population, with increases in their surface extent, with the creation of high-rise buildings for residential and commercial use, and with development underground.

Urbanization can create rapid demand for water resources management, as formerly good sources of freshwater become overused and polluted, and the volume of sewage begins to exceed manageable levels.

Government

The city council of Tehran meets in September 2015.

Local government of cities takes different forms including prominently the municipality (especially in England, in the United States, in India, and in other British colonies; legally, the municipal corporation; municipio in Spain and in Portugal, and, along with municipalidad, in most former parts of the Spanish and Portuguese empires) and the commune (in France and in Chile; or comune in Italy).

The chief official of the city has the title of mayor. Whatever their true degree of political authority, the mayor typically acts as the figurehead or personification of their city.

The city hall in George Town, Malaysia, today serves as the seat of the City Council of Penang Island.

City governments have authority to make laws governing activity within cities, while its jurisdiction is generally considered subordinate (in ascending order) to state/provincial, national, and perhaps international law. This hierarchy of law is not enforced rigidly in practice—for example in conflicts between municipal regulations and national principles such as constitutional rights and property rights. Legal conflicts and issues arise more frequently in cities than elsewhere due to the bare fact of their greater density. Modern city governments thoroughly regulate everyday life in many dimensions, including public and personal health, transport, burial, resource use and extraction, recreation, and the nature and use of buildings. Technologies, techniques, and laws governing these areas—developed in cities—have become ubiquitous in many areas. Municipal officials may be appointed from a higher level of government or elected locally.

Municipal services

The Dublin Fire Brigade in Dublin, Ireland, quenching a severe fire at a hardware store in 1970

Cities typically provide municipal services such as education, through school systems; policing, through police departments; and firefighting, through fire departments; as well as the city’s basic infrastructure. These are provided more or less routinely, in a more or less equal fashion. Responsibility for administration usually falls on the city government, though some services may be operated by a higher level of government, while others may be privately run. Armies may assume responsibility for policing cities in states of domestic turmoil such as America’s King assassination riots of 1968.

Finance

The traditional basis for municipal finance is local property tax levied on real estate within the city. Local government can also collect revenue for services, or by leasing land that it owns. However, financing municipal services, as well as urban renewal and other development projects, is a perennial problem, which cities address through appeals to higher governments, arrangements with the private sector, and techniques such as privatization (selling services into the private sector), corporatization (formation of quasi-private municipally-owned corporations), and financialization (packaging city assets into tradable financial instruments and derivatives). This situation has become acute in deindustrialized cities and in cases where businesses and wealthier citizens have moved outside of city limits and therefore beyond the reach of taxation. Cities in search of ready cash increasingly resort to the municipal bond, essentially a loan with interest and a repayment date. City governments have also begun to use tax increment financing, in which a development project is financed by loans based on future tax revenues which it is expected to yield. Under these circumstances, creditors and consequently city governments place a high importance on city credit ratings.

Governance

The Ripon Building, the headquarters of Greater Chennai Corporation in Chennai. It is one of the oldest city governing corporations in Asia.

Governance includes government but refers to a wider domain of social control functions implemented by many actors including nongovernmental organizations. The impact of globalization and the role of multinational corporations in local governments worldwide, has led to a shift in perspective on urban governance, away from the “urban regime theory” in which a coalition of local interests functionally govern, toward a theory of outside economic control, widely associated in academics with the philosophy of neoliberalism. In the neoliberal model of governance, public utilities are privatized, industry is deregulated, and corporations gain the status of governing actors—as indicated by the power they wield in public-private partnerships and over business improvement districts, and in the expectation of self-regulation through corporate social responsibility. The biggest investors and real estate developers act as the city’s de facto urban planners.

The related concept of good governance places more emphasis on the state, with the purpose of assessing urban governments for their suitability for development assistance. The concepts of governance and good governance are especially invoked in the emergent megacities, where international organizations consider existing governments inadequate for their large populations.

Urban planning

La Plata, Argentina, based on a perfect square with 5196-meter sides, was designed in the 1880s as the new capital of Buenos Aires Province.

Urban planning, the application of forethought to city design, involves optimizing land use, transportation, utilities, and other basic systems, in order to achieve certain objectives. Urban planners and scholars have proposed overlapping theories as ideals for how plans should be formed. Planning tools, beyond the original design of the city itself, include public capital investment in infrastructure and land-use controls such as zoning. The continuous process of comprehensive planning involves identifying general objectives as well as collecting data to evaluate progress and inform future decisions.

Government is legally the final authority on planning but in practice the process involves both public and private elements. The legal principle of eminent domain is used by government to divest citizens of their property in cases where its use is required for a project. Planning often involves tradeoffs—decisions in which some stand to gain and some to lose—and thus is closely connected to the prevailing political situation.

The history of urban planning dates to some of the earliest known cities, especially in the Indus Valley and Mesoamerican civilizations, which built their cities on grids and apparently zoned different areas for different purposes. The effects of planning, ubiquitous in today’s world, can be seen most clearly in the layout of planned communities, fully designed prior to construction, often with consideration for interlocking physical, economic, and cultural systems.

Society

Social structure

Urban society is typically stratified. Spatially, cities are formally or informally segregated along ethnic, economic and racial lines. People living relatively close together may live, work, and play, in separate areas, and associate with different people, forming ethnic or lifestyle enclaves or, in areas of concentrated poverty, ghettoes. While in the US and elsewhere poverty became associated with the inner city, in France it has become associated with the banlieues, areas of urban development which surround the city proper. Meanwhile, across Europe and North America, the racially white majority is empirically the most segregated group. Suburbs in the west, and, increasingly, gated communities and other forms of “privatopia” around the world, allow local elites to self-segregate into secure and exclusive neighborhoods.

Landless urban workers, contrasted with peasants and known as the proletariat, form a growing stratum of society in the age of urbanization. In Marxist doctrine, the proletariat will inevitably revolt against the bourgeoisie as their ranks swell with disenfranchised and disaffected people lacking all stake in the status quo. The global urban proletariat of today, however, generally lacks the status as factory workers which in the nineteenth century provided access to the means of production.

Economics

Historically, cities rely on rural areas for intensive farming to yield surplus crops, in exchange for which they provide money, political administration, manufactured goods, and culture. Urban economics tends to analyze larger agglomerations, stretching beyond city limits, in order to reach a more complete understanding of the local labor market.

Clusters of skyscrapers in Xinyi Special District – the centre of commerce and finance of Taipei City, capital of Taiwan.

As hubs of trade cities have long been home to retail commerce and consumption through the interface of shopping. In the 20th century, department stores using new techniques of advertising, public relations, decoration, and design, transformed urban shopping areas into fantasy worlds encouraging self-expression and escape through consumerism.

In general, the density of cities expedites commerce and facilitates knowledge spillovers, helping people and firms exchange information and generate new ideas. A thicker labor market allows for better skill matching between firms and individuals. Population density enables also sharing of common infrastructure and production facilities, however in very dense cities, increased crowding and waiting times may lead to some negative effects.

Although manufacturing fueled the growth of cities, many now rely on a tertiary or service economy. The services in question range from tourism, hospitality, entertainment, housekeeping and prostitution to grey-collar work in law, finance, and administration.

Culture and communications

Paris is one of the best-known cities in the world.

Cities are typically hubs for education and the arts, supporting universities, museums, temples, and other cultural institutions. They feature impressive displays of architecture ranging from small to enormous and ornate to brutal; skyscrapers, providing thousands of offices or homes within a small footprint, and visible from miles away, have become iconic urban features. Cultural elites tend to live in cities, bound together by shared cultural capital, and themselves playing some role in governance. By virtue of their status as centers of culture and literacy, cities can be described as the locus of civilization, world history, and social change.

Density makes for effective mass communication and transmission of news, through heralds, printed proclamations, newspapers, and digital media. These communication networks, though still using cities as hubs, penetrate extensively into all populated areas. In the age of rapid communication and transportation, commentators have described urban culture as nearly ubiquitous or as no longer meaningful.

Today, a city’s promotion of its cultural activities dovetails with place branding and city marketing, public diplomacy techniques used to inform development strategy; to attract businesses, investors, residents, and tourists; and to create a shared identity and sense of place within the metropolitan area. Physical inscriptions, plaques, and monuments on display physically transmit a historical context for urban places. Some cities, such as Jerusalem, Mecca, and Rome have indelible religious status and for hundreds of years have attracted pilgrims. Patriotic tourists visit Agra to see the Taj Mahal, or New York City to visit the World Trade Center. Elvis lovers visit Memphis to pay their respects at Graceland. Place brands (which include place satisfaction and place loyalty) have great economic value (comparable to the value of commodity brands) because of their influence on the decision-making process of people thinking about doing business in—”purchasing” (the brand of)—a city.

Bread and circuses among other forms of cultural appeal, attract and entertain the masses. Sports also play a major role in city branding and local identity formation. Cities go to considerable lengths in competing to host the Olympic Games, which bring global attention and tourism.

Warfare

Atomic bombing on August 6, 1945, devastated the Japanese city of Hiroshima.

Cities play a crucial strategic role in warfare due to their economic, demographic, symbolic, and political centrality. For the same reasons, they are targets in asymmetric warfare. Many cities throughout history were founded under military auspices, a great many have incorporated fortifications, and military principles continue to influence urban design. Indeed, war may have served as the social rationale and economic basis for the very earliest cities.

Powers engaged in geopolitical conflict have established fortified settlements as part of military strategies, as in the case of garrison towns, America’s Strategic Hamlet Program during the Vietnam War, and Israeli settlements in Palestine. While occupying the Philippines, the US Army ordered local people concentrated into cities and towns, in order to isolate committed insurgents and battle freely against them in the countryside.

Warsaw Old Town after the Warsaw Uprising, 85% of the city was deliberately destroyed.

During World War II, national governments on occasion declared certain cities open, effectively surrendering them to an advancing enemy in order to avoid damage and bloodshed. Urban warfare proved decisive, however, in the Battle of Stalingrad, where Soviet forces repulsed German occupiers, with extreme casualties and destruction. In an era of low-intensity conflict and rapid urbanization, cities have become sites of long-term conflict waged both by foreign occupiers and by local governments against insurgency. Such warfare, known as counterinsurgency, involves techniques of surveillance and psychological warfare as well as close combat, functionally extends modern urban crime prevention, which already uses concepts such as defensible space.

Although capture is the more common objective, warfare has in some cases spelt complete destruction for a city. Mesopotamian tablets and ruins attest to such destruction, as does the Latin motto Carthago delenda est. Since the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and throughout the Cold War, nuclear strategists continued to contemplate the use of “countervalue” targeting: crippling an enemy by annihilating its valuable cities, rather than aiming primarily at its military forces.

Climate change

Climate change and cities are deeply connected. Cites are one of the greatest contributors and likely best opportunities for addressing climate change. Cities are also one of the most vulnerable parts of the human society to the effects of climate change, and likely one of the most important solutions for reducing the environmental impact of humans. More than half of the world’s population is in cities, consuming a large portion of food and goods produced outside of cities. Hence, cities have a significant influence on construction and transportation—two of the key contributors to global warming emissions. Moreover, because of processes that create climate conflict and climate refugees, city areas are expected to grow during the next several decades, stressing infrastructure and concentrating more impoverished peoples in cities.

Because of the high density and effects like the urban heat island effect, weather changes due to climate change are likely to greatly effect cities, exacerbating existing problems, such as air pollution, water scarcity and heat illness in the metropolitan areas. Moreover, because most cities have been built on rivers or coastal areas, cities are frequently vulnerable to the subsequent effects of sea level rise, which cause coastal flooding and erosion , and those effects are deeply connected with other urban environmental problems, like subsidence and aquifer depletion.

A report by the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group described consumption based emissions as having significantly more impact than production-based emissions within cities. The report estimates that 85% of the emissions associated with goods within a city is generated outside of that city. Climate change adaptation and mitigation investments in cities will be important in reducing the impacts of some of the largest contributors of greenhouse gas emissions: for example, increased density allows for redistribution of land use for agriculture and reforestation, improving transportation efficiencies, and greening construction (largely due to cement’s outsized role in climate change and improvements in sustainable construction practices and weatherization). Lists of high impact climate change solutions tend to include city-focused solutions; for example, Project Drawdown recommends several major urban investments, including improved bicycle infrastructure, building retrofitting, district heating, public transit, and walkable cities as important solutions.

Because of this, the international community has formed coalitions of cities (such as the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group and ICLEI) and policy goals, such as Sustainable Development Goal 11 (“sustainable cities and communities”), to activate and focus attention on these solutions.

Infrastructure

Traffic congestion in Bandung, West Java

Urban infrastructure involves various physical networks and spaces necessary for transportation, water use, energy, recreation, and public functions. Infrastructure carries a high initial cost in fixed capital (pipes, wires, plants, vehicles, etc.) but lower marginal costs and thus positive economies of scale. Because of the higher barriers to entry, these networks have been classified as natural monopolies, meaning that economic logic favors control of each network by a single organization, public or private.

Infrastructure in general (if not every infrastructure project) plays a vital role in a city’s capacity for economic activity and expansion, underpinning the very survival of the city’s inhabitants, as well as technological, commercial, industrial, and social activities. Structurally, many infrastructure systems take the form of networks with redundant links and multiple pathways, so that the system as a whole continue to operate even if parts of it fail. The particulars of a city’s infrastructure systems have historical path dependence because new development must build from what exists already.

Megaprojects such as the construction of airports, power plants, and railways require large upfront investments and thus tend to require funding from national government or the private sector. Privatization may also extend to all levels of infrastructure construction and maintenance.

Urban infrastructure ideally serves all residents equally but in practice may prove uneven—with, in some cities, clear first-class and second-class alternatives.

Utilities

Aqueduct of Segovia in Spain

Public utilities (literally, useful things with general availability) include basic and essential infrastructure networks, chiefly concerned with the supply of water, electricity, and telecommunications capability to the populace.

Sanitation, necessary for good health in crowded conditions, requires water supply and waste management as well as individual hygiene. Urban water systems include principally a water supply network and a network (sewerage system) for sewage and stormwater. Historically, either local governments or private companies have administered urban water supply, with a tendency toward government water supply in the 20th century and a tendency toward private operation at the turn of the twenty-first. The market for private water services is dominated by two French companies, Veolia Water (formerly Vivendi) and Engie (formerly Suez), said to hold 70% of all water contracts worldwide.

Modern urban life relies heavily on the energy transmitted through electricity for the operation of electric machines (from household appliances to industrial machines to now-ubiquitous electronic systems used in communications, business, and government) and for traffic lights, streetlights and indoor lighting. Cities rely to a lesser extent on hydrocarbon fuels such as gasoline and natural gas for transportation, heating, and cooking. Telecommunications infrastructure such as telephone lines and coaxial cables also traverse cities, forming dense networks for mass and point-to-point communications.

Transportation

Because cities rely on specialization and an economic system based on wage labour, their inhabitants must have the ability to regularly travel between home, work, commerce, and entertainment. Citydwellers travel foot or by wheel on roads and walkways, or use special rapid transit systems based on underground, overground, and elevated rail. Cities also rely on long-distance transportation (truck, rail, and airplane) for economic connections with other cities and rural areas.

Gautrain stopped at the O. R. Tambo International Airport in Johannesburg

Historically, city streets were the domain of horses and their riders and pedestrians, who only sometimes had sidewalks and special walking areas reserved for them. In the west, bicycles or (velocipedes), efficient human-powered machines for short- and medium-distance travel, enjoyed a period of popularity at the beginning of the twentieth century before the rise of automobiles. Soon after, they gained a more lasting foothold in Asian and African cities under European influence. In western cities, industrializing, expanding, and electrifying at this time, public transit systems and especially streetcars enabled urban expansion as new residential neighborhoods sprung up along transit lines and workers rode to and from work downtown.

Since the mid-twentieth century, cities have relied heavily on motor vehicle transportation, with major implications for their layout, environment, and aesthetics. (This transformation occurred most dramatically in the US—where corporate and governmental policies favored automobile transport systems—and to a lesser extent in Europe.) The rise of personal cars accompanied the expansion of urban economic areas into much larger metropolises, subsequently creating ubiquitous traffic issues with accompanying construction of new highways, wider streets, and alternative walkways for pedestrians. However, severe traffic jams still occur regularly in cities around the world, as private car ownership and urbanization continue to increase, overwhelming existing urban street networks.

Transjakarta in Indonesia, is the longest Bus Rapid Transit system in the world

The urban bus system, the world’s most common form of public transport, uses a network of scheduled routes to move people through the city, alongside cars, on the roads. Economic function itself also became more decentralized as concentration became impractical and employers relocated to more car-friendly locations (including edge cities). Some cities have introduced bus rapid transit systems which include exclusive bus lanes and other methods for prioritizing bus traffic over private cars. Many big American cities still operate conventional public transit by rail, as exemplified by the ever-popular New York City Subway system. Rapid transit is widely used in Europe and has increased in Latin America and Asia.

Baana, a shared path rail trail in the city center of Helsinki

Walking and cycling (“non-motorized transport”) enjoy increasing favor (more pedestrian zones and bike lanes) in American and Asian urban transportation planning, under the influence of such trends as the Healthy Cities movement, the drive for sustainable development, and the idea of a carfree city. Techniques such as road space rationing and road use charges have been introduced to limit urban car traffic.

Housing

Housing of residents presents one of the major challenges every city must face. Adequate housing entails not only physical shelters but also the physical systems necessary to sustain life and economic activity. Home ownership represents status and a modicum of economic security, compared to renting which may consume much of the income of low-wage urban workers. Homelessness, or lack of housing, is a challenge currently faced by millions of people in countries rich and poor.

Ecology

This urban scene in Paramaribo features a few plants growing amidst solid waste and rubble behind some houses.

Urban ecosystems, influenced as they are by the density of human buildings and activities differ considerably from those of their rural surroundings. Anthropogenic buildings and waste, as well as cultivation in gardens, create physical and chemical environments which have no equivalents in wilderness, in some cases enabling exceptional biodiversity. They provide homes not only for immigrant humans but also for immigrant plants, bringing about interactions between species which never previously encountered each other. They introduce frequent disturbances (construction, walking) to plant and animal habitats, creating opportunities for recolonization and thus favoring young ecosystems with r-selected species dominant. On the whole, urban ecosystems are less complex and productive than others, due to the diminished absolute amount of biological interactions.

Typical urban fauna include insects (especially ants), rodents (mice, rats), and birds, as well as cats and dogs (domesticated and feral). Large predators are scarce.

Profile of an urban heat island.

Cities generate considerable ecological footprints, locally and at longer distances, due to concentrated populations and technological activities. From one perspective, cities are not ecologically sustainable due to their resource needs. From another, proper management may be able to ameliorate a city’s ill effects. Air pollution arises from various forms of combustion, including fireplaces, wood or coal-burning stoves, other heating systems, and internal combustion engines. Industrialized cities, and today third-world megacities, are notorious for veils of smog (industrial haze) which envelop them, posing a chronic threat to the health of their millions of inhabitants. Urban soil contains higher concentrations of heavy metals (especially lead, copper, and nickel) and has lower pH than soil in comparable wilderness.

Modern cities are known for creating their own microclimates, due to concrete, asphalt, and other artificial surfaces, which heat up in sunlight and channel rainwater into underground ducts. The temperature in New York City exceeds nearby rural temperatures by an average of 2–3 °C and at times 5–10 °C differences have been recorded. This effect varies nonlinearly with population changes (independently of the city’s physical size). Aerial particulates increase rainfall by 5–10%. Thus, urban areas experience unique climates, with earlier flowering and later leaf dropping than in nearby country.

Poor and working-class people face disproportionate exposure to environmental risks (known as environmental racism when intersecting also with racial segregation). For example, within the urban microclimate, less-vegetated poor neighborhoods bear more of the heat (but have fewer means of coping with it).

St Stephen’s Green, an urban park in Dublin, Ireland

One of the main methods of improving the urban ecology is including in the cities more natural areas: Parks, Gardens, Lawns, and Trees. These areas improve the health, the well-being of the human, animal, and plant population of the cities. Generally they are called Urban open space (although this word does not always mean green space), Green space, Urban greening. Well-maintained urban trees can provide many social, ecological, and physical benefits to the residents of the city.

A study published in Nature’s Scientific Reports journal in 2019 found that people who spent at least two hours per week in nature, were 23 percent more likely to be satisfied with their life and were 59 percent more likely to be in good health than those who had zero exposure. The study used data from almost 20,000 people in the UK. Benefits increased for up to 300 minutes of exposure. The benefits applied to men and women of all ages, as well as across different ethnicities, socioeconomic status, and even those with long-term illnesses and disabilities.

Central Park in New York City

People who did not get at least two hours — even if they surpassed an hour per week — did not get the benefits.

The study is the latest addition to a compelling body of evidence for the health benefits of nature. Many doctors already give nature prescriptions to their patients.

The study didn’t count time spent in a person’s own yard or garden as time in nature, but the majority of nature visits in the study took place within two miles from home. “Even visiting local urban green spaces seems to be a good thing,” Dr. White said in a press release. “Two hours a week is hopefully a realistic target for many people, especially given that it can be spread over an entire week to get the benefit.”

World city system

As the world becomes more closely linked through economics, politics, technology, and culture (a process called globalization), cities have come to play a leading role in transnational affairs, exceeding the limitations of international relations conducted by national governments. This phenomenon, resurgent today, can be traced back to the Silk Road, Phoenicia, and the Greek city-states, through the Hanseatic League and other alliances of cities. Today the information economy based on high-speed internet infrastructure enables instantaneous telecommunication around the world, effectively eliminating the distance between cities for the purposes of stock markets and other high-level elements of the world economy, as well as personal communications and mass media.

Global city

Stock exchanges, characteristic features of the top global cities, are interconnected hubs for capital. Here, a delegation from Australia is shown visiting the London Stock Exchange.

A global city, also known as a world city, is a prominent centre of trade, banking, finance, innovation, and markets. Saskia Sassen used the term “global city” in her 1991 work, The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo to refer to a city’s power, status, and cosmopolitanism, rather than to its size. Following this view of cities, it is possible to rank the world’s cities hierarchically. Global cities form the capstone of the global hierarchy, exerting command and control through their economic and political influence. Global cities may have reached their status due to early transition to post-industrialism or through inertia which has enabled them to maintain their dominance from the industrial era. This type of ranking exemplifies an emerging discourse in which cities, considered variations on the same ideal type, must compete with each other globally to achieve prosperity.

Critics of the notion point to the different realms of power and interchange. The term “global city” is heavily influenced by economic factors and, thus, may not account for places that are otherwise significant. Paul James, for example argues that the term is “reductive and skewed” in its focus on financial systems.

Multinational corporations and banks make their headquarters in global cities and conduct much of their business within this context. American firms dominate the international markets for law and engineering and maintain branches in the biggest foreign global cities.

Global cities feature concentrations of extremely wealthy and extremely poor people. Their economies are lubricated by their capacity (limited by the national government’s immigration policy, which functionally defines the supply side of the labor market) to recruit low- and high-skilled immigrant workers from poorer areas. More and more cities today draw on this globally available labor force.

Modern global cities, like New York City, often include large central business districts (CBDs) that serve as hubs for economic activity. A panorama of Manhattan, the world’s largest CBD, is shown from February 2018.

- Riverside Church

- Time Warner Center

- 220 Central Park South

- Central Park Tower

- One57

- 432 Park Avenue

- 53W53

- Chrysler Building

- Bank of America Tower

- Conde Nast Building

- The New York Times Building

- Empire State Building

- Manhattan West

- a: 55 Hudson Yards, b: 35 Hudson Yards, c: 10 Hudson Yards, d: 15 Hudson Yards

- 56 Leonard Street

- 8 Spruce Street

- Woolworth Building

- 70 Pine Street

- 30 Park Place

- 40 Wall Street

- Three World Trade Center

- Four World Trade Center

- One World Trade Center

Transnational activity

Cities increasingly participate in world political activities independently of their enclosing nation-states. Early examples of this phenomenon are the sister city relationship and the promotion of multi-level governance within the European Union as a technique for European integration. Cities including Hamburg, Prague, Amsterdam, The Hague, and City of London maintain their own embassies to the European Union at Brussels.

New urban dwellers may increasingly not simply as immigrants but as transmigrants, keeping one foot each (through telecommunications if not travel) in their old and their new homes.

Global governance

Cities participate in global governance by various means including membership in global networks which transmit norms and regulations. At the general, global level, United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG) is a significant umbrella organization for cities; regionally and nationally, Eurocities, Asian Network of Major Cities 21, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities the National League of Cities, and the United States Conference of Mayors play similar roles. UCLG took responsibility for creating Agenda 21 for culture, a program for cultural policies promoting sustainable development, and has organized various conferences and reports for its furtherance.

Networks have become especially prevalent in the arena of environmentalism and specifically climate change following the adoption of Agenda 21. Environmental city networks include the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, World Association of Major Metropolises (“Metropolis”), the United Nations Global Compact Cities Programme, the Carbon Neutral Cities Alliance (CNCA), the Covenant of Mayors and the Compact of Mayors, ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability, and the Transition Towns network.

Cities with world political status as meeting places for advocacy groups, non-governmental organizations, lobbyists, educational institutions, intelligence agencies, military contractors, information technology firms, and other groups with a stake in world policymaking. They are consequently also sites for symbolic protest.

United Nations System

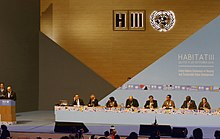

The United Nations System has been involved in a series of events and declarations dealing with the development of cities during this period of rapid urbanization.

- The Habitat I conference in 1976 adopted the “Vancouver Declaration on Human Settlements” which identifies urban management as a fundamental aspect of development and establishes various principles for maintaining urban habitats.

- Citing the Vancouver Declaration, the UN General Assembly in December 1977 authorized the United Nations Commission Human Settlements and the HABITAT Centre for Human Settlements, intended to coordinate UN activities related to housing and settlements.

- The 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro resulted in a set of international agreements including Agenda 21 which establishes principles and plans for sustainable development.

World Assembly of Mayors at Habitat III conference in Quito.

- The Habitat II conference in 1996 called for cities to play a leading role in this program, which subsequently advanced the Millennium Development Goals and Sustainable Development Goals.

- In January 2002 the UN Commission on Human Settlements became an umbrella agency called the United Nations Human Settlements Programme or UN-Habitat, a member of the United Nations Development Group.

- The Habitat III conference of 2016 focused on implementing these goals under the banner of a “New Urban Agenda”. The four mechanisms envisioned for effecting the New Urban Agenda are (1) national policies promoting integrated sustainable development, (2) stronger urban governance, (3) long-term integrated urban and territorial planning, and (4) effective financing frameworks. Just before this conference, the European Union concurrently approved an “Urban Agenda for the European Union” known as the Pact of Amsterdam.

UN-Habitat coordinates the UN urban agenda, working with the UN Environmental Programme, the UN Development Programme, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the World Health Organization, and the World Bank.

World Bank headquarters in Washington, D.C., United States

The World Bank, a United Nations specialized agency, has been a primary force in promoting the Habitat conferences, and since the first Habitat conference has used their declarations as a framework for issuing loans for urban infrastructure. The bank’s structural adjustment programs contributed to urbanization in the Third World by creating incentives to move to cities. The World Bank and UN-Habitat in 1999 jointly established the Cities Alliance (based at the World Bank headquarters in Washington, D.C.) to guide policymaking, knowledge sharing, and grant distribution around the issue of urban poverty. (UN-Habitat plays an advisory role in evaluating the quality of a locality’s governance.) The Bank’s policies have tended to focus on bolstering real estate markets through credit and technical assistance.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, UNESCO has increasingly focused on cities as key sites for influencing cultural governance. It has developed various city networks including the International Coalition of Cities against Racism and the Creative Cities Network. UNESCO’s capacity to select World Heritage Sites gives the organization significant influence over cultural capital, tourism, and historic preservation funding.

Representation in culture

John Martin’s The Fall of Babylon (1831), depicting chaos as the Persian army occupies Babylon, also symbolizes the ruin of decadent civilization in modern times. Lightning striking the Babylonian ziggurat (also representing the Tower of Babel) indicates God’s judgment against the city.

Cities figure prominently in traditional Western culture, appearing in the Bible in both evil and holy forms, symbolized by Babylon and Jerusalem. Cain and Nimrod are the first city builders in the Book of Genesis. In Sumerian mythology Gilgamesh built the walls of Uruk.

Cities can be perceived in terms of extremes or opposites: at once liberating and oppressive, wealthy and poor, organized and chaotic. The name anti-urbanism refers to various types of ideological opposition to cities, whether because of their culture or their political relationship with the country. Such opposition may result from identification of cities with oppression and the ruling elite. This and other political ideologies strongly influence narratives and themes in discourse about cities. In turn, cities symbolize their home societies.

Writers, painters, and filmmakers have produced innumerable works of art concerning the urban experience. Classical and medieval literature includes a genre of descriptiones which treat of city features and history. Modern authors such as Charles Dickens and James Joyce are famous for evocative descriptions of their home cities. Fritz Lang conceived the idea for his influential 1927 film Metropolis while visiting Times Square and marveling at the nighttime neon lighting. Other early cinematic representations of cities in the twentieth century generally depicted them as technologically efficient spaces with smoothly functioning systems of automobile transport. By the 1960s, however, traffic congestion began to appear in such films as The Fast Lady (1962) and Playtime (1967).

Literature, film, and other forms of popular culture have supplied visions of future cities both utopian and dystopian. The prospect of expanding, communicating, and increasingly interdependent world cities has given rise to images such as Nylonkong (New York, London, Hong Kong) and visions of a single world-encompassing ecumenopolis.