The British Armed Forces, also known as Her Majesty’s Armed Forces, are the military services responsible for the defence of the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and the Crown dependencies. They also promote the UK’s wider interests, support international peacekeeping efforts and provide humanitarian aid.

Since the formation of the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707 (later succeeded by the United Kingdom), the armed forces have seen action in a number of major wars involving the world’s great powers, including the Seven Years’ War, the American Revolutionary War, the Napoleonic Wars, the Crimean War, the First World War, and the Second World War. Repeatedly emerging victorious from conflicts has allowed Britain to establish itself as one of the world’s leading military and economic powers. Today, the British Armed Forces consist of: the Royal Navy, a blue-water navy with a fleet of 79 commissioned ships, together with the Royal Marines, a highly specialised amphibious light infantry force; the British Army, the UK’s principal land warfare branch; and the Royal Air Force, a technologically sophisticated air force with a diverse operational fleet consisting of both fixed-wing and rotary aircraft. The British Armed Forces include standing forces, Regular Reserve, Volunteer Reserves and Sponsored Reserves.

The head of the Armed Forces is the British monarch, currently Queen Elizabeth II, to whom members of the forces swear allegiance. Long-standing constitutional convention, however, has vested de facto executive authority, by the exercise of royal prerogative, in the prime minister and the secretary of state for defence. The prime minister (acting with the Cabinet) makes the key decisions on the use of the armed forces. The UK Parliament approves the continued existence of the British Army by passing an Armed Forces Act at least once every five years, as required by the Bill of Rights 1689. The Royal Navy, Royal Air Force and Royal Marines among with all other forces do not require this act. The armed forces are managed by the Defence Council of the Ministry of Defence, headed by the secretary of state for defence.

The United Kingdom is one of five recognised nuclear powers, is a permanent member on the United Nations Security Council, is a founding and leading member of the NATO military alliance, and is party to the Five Power Defence Arrangements. Overseas garrisons and training facilities are maintained at Ascension Island, Bahrain, Belize, Bermuda, British Indian Ocean Territory, Brunei, Canada, Cyprus, the Falkland Islands, Germany, Gibraltar, Kenya, Montserrat, Nepal, Qatar, Singapore and the United States.

History

Organisational history

With the Acts of Union 1707, the armed forces of England and Scotland were merged into the armed forces of the Kingdom of Great Britain.

There were originally several naval and several military regular and reserve forces, although most of these were consolidated into the Royal Navy or the British Army during the 19th and 20th Centuries (the Royal Naval Air Service and the Royal Flying Corps of the British Army, by contrast, were separated from their parent forces in 1918 and amalgamated to form a new force, the Royal Air Force, which would have complete responsibility for naval, military and strategic aviation until the Second World War).

Naval forces included the Royal Navy, the Waterguard (subsequently HM Coastguard), and Sea Fencibles and River Fencibles formed as and when required for the duration of emergencies. The Merchant Navy and offshore fishing boat crews were also an important reserve to the armed naval forces.

The British military (those parts of the British Armed Forces tasked with land warfare, as opposed to the naval forces) historically was divided into a number of military forces, of which the British Army (also referred to historically as the Regular Army and the Regular Force) was only one. The oldest of these organisations was the Militia Force (also referred to as the Constitutional Force), which (in the Kingdom of England) was originally the main military defensive force (there otherwise were originally only Royal bodyguards, including the Yeomen Warders and the Yeomen of the Guard, with armies raised only temporarily for expeditions overseas), made up of civilians embodied for annual training or emergencies, and had used various schemes of compulsory service during different periods of its long existence.

The Militia was originally an all infantry force, organised at the city or county level, and members were not required to serve outside of their recruitment area, although the area within which militia units in Britain could be posted was increased to anywhere in the Britain during the Eighteenth Century, and Militia coastal artillery, field artillery, and engineers units were introduced from the 1850s. The Yeomanry was a mounted force that could be mobilised in times of war or emergency. Volunteer Force units were also frequently raised during wartime, which did not rely on compulsory service and hence attracted recruits keen to avoid the Militia. These were seen as a useful way to add to military strength economically during wartime, but otherwise as a drain on the Militia and so were not normally maintained in peacetime, although in Bermuda prominent propertied men were still appointed Captains of Forts, taking charge of maintaining and commanding fortified Coastal artillery batteries and manned by volunteers (reinforced in wartime by embodied militiamen), defending the colony’s coast from the Seventeenth Century to the Nineteenth Century (when all of the batteries were taken over by the regular Royal Artillery). The Militia system was extended to a number of English (subsequently British) colonies, beginning with Virginia and Bermuda. In some colonies, Troops of Horse or other mounted units similar to the Yeomanry were also created. The Militia and Volunteer units of a colony were generally considered to be separate forces from the Home Militia Force and Volunteer Force in the United Kingdom, and from the Militia Forces and Volunteer Forces of other colonies. Where a colony had more than one Militia or Volunteer unit, they would be grouped as a Militia or Volunteer Force for that colony, such as the Jamaica Volunteer Defence Force, which comprised the St. Andrew Rifle Corps (or Kingston Infantry Volunteers), the Jamaica Corps of Scouts, and the Jamaica Reserve Regiment, but not the Jamaica Militia Artillery. In smaller colonies with a single militia or volunteer unit, that single unit would still be considered to be listed within a force, or in some case might be named a force rather than a regiment or corps, such as is the case for the Falkland Islands Defence Force and the ‘Royal Montserrat Defence Force. The Militia, Yeomanry and Volunteer Forces collectively were known as the Reserve Forces, Auxiliary Forces, or Local Forces. Officers of these forces could not sit on Courts Martial of regular forces personnel. The Mutiny Act did not apply to members of the Reserve Forces.

The other regular military force that existed alongside the British Army was the Board of Ordnance, which included the Ordnance Military Corps (made up of the Royal Artillery, Royal Engineers, and the Royal Sappers and Miners), as well as the originally-civilian Commissariat Stores and transport departments, as well as barracks departments, ordnance factories and various other functions supporting the various naval and military forces. The English Army, subsequently the British Army once Scottish regiments were moved onto its establishment following the Union of the Kingdoms of Scotland and England, was originally a separate force from these, but absorbed the Ordnance Military Corps and various previously civilian departments after the Board of Ordnance was abolished in 1855. The Reserve Forces (which referred to the Home Yeomanry, Militia and Volunteer Forces before the 1859 creation of the British Army Regular Reserve by Secretary of State for War Sidney Herbert, and re-organised under the Reserve Force Act, 1867) were increasingly integrated with the British Army through a succession of reforms over the last two decades of the Nineteenth Century (by the end of the century, at the latest, any unit wholly or partly funded from Army Funds was considered part of the British Army) and the early years of the Twentieth Century, whereby the Reserve Forces units mostly lost their own identities and became numbered Territorial Force sub-units of regular British Army corps or regiments (the Home Militia had followed this path, with the Militia Infantry units becoming numbered battalions of British Army regiments, and the Militia Artillery integrating within Royal Artillery territorial divisions in 1882 and 1889, and becoming parts of the Royal Field Artillery or Royal Garrison Artillery in 1902 (though retaining their traditional corps names), but was not merged into the Territorial Force when it was created in 1908 (by the merger of the Yeomanry and Volunteer Force). The Militia was instead renamed the Special Reserve, and was permanently suspended after the First World War (although a handful of Militia units survived in the United Kingdom, its colonies, and the Crown Dependencies). Unlike the Home, Imperial Fortress and Crown Dependency Militia and Volunteer units and forces that continued to exist after the First World War, although parts of the British military, most were not considered parts of the British Army unless they received Army Funds (as was the case for the Bermuda Militia Artillery and the Bermuda Volunteer Rifle Corps), which was generally only the case for those in the Channel Islands or the Imperial Fortress colonies (Nova Scotia, before Canadian confederation, Bermuda, Gibraltar, and Malta). Today, the British Army is the only Home British military force (unless the Army Cadet Force and the Combined Cadet Force are considered), including both the regular army and the forces it absorbed, though British military units organised on Territorial lines remain in British Overseas Territories that are still not considered formally part of the British Army, with only the Royal Gibraltar Regiment and the Royal Bermuda Regiment (an amalgam of the old Bermuda Militia Artillery and Bermuda Volunteer Rifle Corps) appearing on the British Army order of precedence and in the Army List.

Confusingly, and similarly to the dual meaning of the word Corps in the British Army (by example, the 1st Battalion of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps was in 1914 part of the 6th Brigade that was part of the 2nd Infantry Division, which was itself part of 1st Army Corps), the British Army sometimes also used the term expeditionary force or field force to describe a body made up of British Army units, most notably the British Expeditionary Force, or of a mixture of British Army, Indian Army, or Imperial auxiliary units, such as the Malakand Field Force (this is similarly to the naval use of the term task force). In this usage, force is used to describe a self-reliant body able to act without external support, at least within the parameters of the task or objective for which it is employed.

Empire and World Wars

A modern reproduction of an 1805 poster commemorating the Battle of Trafalgar

During the later half of the seventeenth century, and in particular, throughout the eighteenth century, British foreign policy sought to contain the expansion of rival European powers through military, diplomatic and commercial means – especially of its chief competitors; Spain, the Netherlands and France. This saw Britain engage in a number of intense conflicts over colonial possessions and world trade, including a long string of Anglo-Spanish and Anglo-Dutch wars, as well as a series of “world wars” with France, such as; the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802) and the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815). During the Napoleonic wars, the Royal Navy victory at Trafalgar (1805) under the command of Horatio Nelson (aboard HMS Victory) marked the culmination of British maritime supremacy, and left the Navy in a position of uncontested hegemony at sea. By 1815 and the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, Britain had risen to become the world’s dominant great power and the British Empire subsequently presided over a period of relative peace, known as Pax Britannica.

With Britain’s old rivals no-longer a threat, the nineteenth century saw the emergence of a new rival, the Russian Empire, and a strategic competition in what became known as The Great Game for supremacy in Central Asia. Britain feared that Russian expansionism in the region would eventually threaten the Empire in India. In response, Britain undertook a number of pre-emptive actions against perceived Russian ambitions, including the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839–1842), the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878–1880) and the British expedition to Tibet (1903–1904). During this period, Britain also sought to maintain the balance of power in Europe, particularly against Russian expansionism, who at the expense of the waning Ottoman Empire had ambitions to “carve up the European part of Turkey”. This ultimately led to British involvement in the Crimean War (1854–1856) against the Russian Empire.

Soldiers from the Royal Irish Rifles in the Battle of the Somme’s trenches 1916

The beginning of the twentieth century served to reduce tensions between Britain and the Russian Empire, partly due to the emergence of a unified German Empire. The era brought about an Anglo-German naval arms race which encouraged significant advancements in maritime technology (e.g. Dreadnoughts, torpedoes and submarines), and in 1906, Britain had determined that its only likely naval enemy was Germany. The accumulated tensions in European relations finally broke out into the hostilities of the First World War (1914–1918), in what is recognised today, as the most devastating war in British military history, with nearly 800,000 men killed and over 2 million wounded. Allied victory resulted in the defeat of the Central Powers, the end of the German Empire, the Treaty of Versailles and the establishment of the League of Nations.

British commandos during the Second World War

Although Germany had been defeated during the First World War, by 1933 fascism had given rise to Nazi Germany, which under the leadership of Adolf Hitler re-militarised in defiance of the Treaty of Versailles. Once again tensions accumulated in European relations, and following Germany’s invasion of Poland in September 1939, the Second World War began (1939–1945). The conflict was the most widespread in British history, with British Empire and Commonwealth troops fighting in campaigns from Europe and North Africa, to the Middle East and the Far East. Approximately 390,000 British Empire and Commonwealth troops lost their lives. Allied victory resulted in the defeat of the Axis powers and the establishment of the United Nations (replacing the League of nations).

The Cold War

The Vulcan Bomber was the mainstay of Britain’s airborne nuclear capability for much of the Cold War.

Post–Second World War economic and political decline, as well as changing attitudes in British society and government, were reflected by the armed forces’ contracting global role, and later epitomised by its political defeat during the Suez Crisis (1956). Reflecting Britain’s new role in the world and the escalation of the Cold War (1947–1991), the country became a founding member of the NATO military alliance in 1949. Defence Reviews, such as those in 1957 and 1966, announced significant reductions in conventional forces, the pursuement of a doctrine based on nuclear deterrence, and a permanent military withdrawal East of Suez. By the mid-1970s, the armed forces had reconfigured to focus on the responsibilities allocated to them by NATO. The British Army of the Rhine and RAF Germany consequently represented the largest and most important overseas commitments that the armed forces had during this period, while the Royal Navy developed an anti-submarine warfare specialisation, with a particular focus on countering Soviet submarines in the Eastern Atlantic and North Sea.

While NATO obligations took increased prominence, Britain nonetheless found itself engaged in a number of low-intensity conflicts, including a spate of insurgencies against colonial occupation. However the Dhofar Rebellion (1962–1976) and The Troubles (1969–1998) emerged as the primary operational concerns of the armed forces. Perhaps the most important conflict during the Cold War, at least in the context of British defence policy, was the Falklands War (1982).

Since the end of the Cold War, an increasingly international role for the armed forces has been pursued, with re-structuring to deliver a greater focus on expeditionary warfare and power projection. This entailed the armed forces often constituting a major component in peacekeeping and humanitarian missions under the auspices of the United Nations, NATO, and other multinational operations, including: peacekeeping responsibilities in the Balkans and Cyprus, the 2000 intervention in Sierra Leone and participation in the UN-mandated no-fly zone over Libya (2011). Post-September 11, the armed forces have been heavily committed to the War on Terror (2001–present), with lengthy campaigns in Afghanistan (2001–present) and Iraq (2003–2009), and more recently as part of the Military intervention against ISIL (2014–present). Britain’s military intervention against Islamic State was expanded following a parliamentary vote to launch a bombing campaign over Syria; an extension of the bombing campaign requested by the Iraqi government against the same group. In addition to the aerial campaign, the British Army has trained and supplied allies on the ground and the Special Air Service, the Special Boat Service, and the Special Reconnaissance Regiment (British special forces) has carried out various missions on the ground in both Syria and Iraq.

Figures released by the Ministry of Defence on 31 March 2016 show that 7,185 British Armed Forces personnel have lost their lives in medal earning theatres since the end of the Second World War.

Today

Elongated tri-service emblem

Command organisation

Commander-in-Chief the Queen Elizabeth II riding Burmese at the 1986 Trooping the Colour ceremony

The Ministry of Defence building at Whitehall, Westminster, London

As sovereign and head of state, Queen Elizabeth II is Head of the Armed Forces and their Commander-in-Chief. Long-standing constitutional convention, however, has vested de facto executive authority, by the exercise of royal prerogative powers, in the prime minister and the secretary of state for defence, and the prime minister (acting with the support of the Cabinet) makes the key decisions on the use of the armed forces. The Queen, however, remains the ultimate authority of the military, with officers and personnel swearing allegiance to the monarch. It has been claimed that this includes the power to prevent unconstitutional use of the armed forces, including its nuclear weapons.

The Ministry of Defence is the Government department and highest level of military headquarters charged with formulating and executing defence policy for the armed forces; it currently employs 56,860 civilian staff as of 1 October 2015. The department is controlled by the secretary of state for defence and contains three deputy appointments: Minister of State for the Armed Forces, Minister for Defence Procurement, and Minister for Veterans’ Affairs. Responsibility for the management of the forces is delegated to a number of committees: the Defence Council, Chiefs of Staff Committee, Defence Management Board and three single-service boards. The Defence Council, composed of senior representatives of the services and the Ministry of Defence, provides the “formal legal basis for the conduct of defence”. The three constituent single-service committees (Admiralty Board, Army Board and Air Force Board) are chaired by the secretary of state for defence.

The chief of the defence staff is the professional head of the armed forces and is an appointment that can be held by an admiral, air chief marshal or general. Before the practice was discontinued in the 1990s, those who were appointed to the position of CDS had been elevated to the most senior rank in their respective service (a 5-star rank). The CDS, along with the permanent under secretary, are the principal advisers to the departmental minister. The three services have their own respective professional chiefs: the First Sea Lord, the chief of the general staff and the chief of the air staff.

Personnel

Welsh Guards Trooping the Colour

The British Armed Forces are a professional force with a strength of 153,290 UK Regulars and Gurkhas, 37,420 Volunteer Reserves and 8,170 “Other Personnel” as of 1 April 2021. This gives a total strength of 198,880 “UK Service Personnel”. As a percentage breakdown of UK Service Personnel, 77.1% are UK Regulars and Gurkhas, 18.8% are Volunteer Reserves and 4.1% are composed of Other Personnel. In addition, all ex-Regular personnel retain a “statutory liability for service” and are liable to be recalled (under Section 52 of the Reserve Forces Act (RFA) 1996) for duty during wartime, which is known as the Regular Reserve. MoD publications since April 2013 no longer report the entire strength of the Regular Reserve, instead they only give a figure for Regular Reserves who serve under a fixed-term reserve contract. These contracts are similar in nature to those of the Volunteer Reserve. As of 1 April 2015, Regular Reserves serving under a fixed-term contract numbered 44,600 personnel.

The distribution of personnel between the services and categories of service on 1 April 2021 was as follows:

| Service | Regular | Volunteer Reserve |

Other Personnel |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Navy | 33,850 | 4,080 | 2,480 | 40,400 |

| Army | 86,240 | 30,040 | 4,380 | 120,660 |

| Air Force | 33,200 | 3,300 | 1,310 | 37,810 |

| Total | 153,290 | 37,420 | 8,170 | 198,880 |

As of 1 October 2017, there were a total of 9,330 Regular service personnel stationed outside of the United Kingdom, 3,820 of those were located in Germany. 138,040 Regular service personnel were stationed in the United Kingdom, the majority located in the South East and South West of England with 37,520 and 36,790 Regular service personnel, respectively.

Defence expenditure

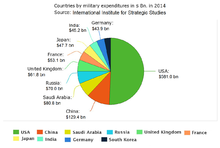

Top ten military expenditures in billion US$ in 2014

According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies and the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, the United Kingdom has the fourth- or fifth-largest defence budget in the world. For comparisons sake, this sees Britain spending more in absolute terms than France, Germany, India or Japan, a similar amount to that of Russia, but less than China, Saudi Arabia or the United States. In September 2011, according to Professor Malcolm Chalmers of the Royal United Services Institute, current “planned levels of defence spending should be enough for the United Kingdom to maintain its position as one of the world’s top military powers, as well as being one of NATO-Europe’s top military powers. Its edge – not least its qualitative edge – in relation to rising Asian powers seems set to erode, but will remain significant well into the 2020s, and possibly beyond.” The Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015 committed to spending 2% of GDP on defence and announced a £178 billion investment over ten years in new equipment and capabilities.

Nuclear weapons

A Trident II SLBM being launched from a Vanguard-class submarine

The United Kingdom is one of five recognised nuclear weapon states under the Non-Proliferation Treaty and maintains an independent nuclear deterrent, currently consisting of four Vanguard-class ballistic missile submarines, UGM-133 Trident II submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and 160 operational thermonuclear warheads. This is known as Trident in both public and political discourse (with nomenclature taken after the UGM-133 Trident II ballistic missile). Trident is operated by the Royal Navy Submarine Service, charged with delivering a ‘Continuous At-Sea Deterrent’ (CASD) capability, whereby one of the Vanguard-class strategic submarines is always on patrol. According to the British Government, since the introduction of Polaris (Tridents predecessor) in the 1960s, from April 1969 “the Royal Navy’s ballistic missile boats have not missed a single day on patrol”, giving what the Defence Council described in 1980 as a deterrent “effectively invulnerable to pre-emptive attack”. As of 2015, it has been British Government policy for the Vanguard-class strategic submarines to carry no more than 40 nuclear warheads, delivered by eight UGM-133 Trident II ballistic missiles. In contrast with the other recognised nuclear weapon states, the United Kingdom operates only a submarine-based delivery system, having decommissioned its tactical WE.177 free-fall bombs in 1998.

The House of Commons voted on 18 July 2016 in favour of replacing the Vanguard-class submarines with a new generation of Dreadnought-class submarines. The programme will also contribute to extending the life of the UGM-133 Trident II ballistic missiles and modernise the infrastructure associated with the CASD.

Former weapons of mass destruction possessed by the United Kingdom include both biological and chemical weapons. These were renounced in 1956 and subsequently destroyed.

Overseas military installations