The Chutia Kingdom (also Sadiya) was a late medieval state that developed around Sadiya in present Assam and adjoining areas in Arunachal Pradesh. It extended over almost the entire region of present districts of Lakhimpur, Dhemaji, Tinsukia and some parts of Dibrugarh in Assam, as well as the plains and foothills of Arunachal Pradesh. The kingdom fell in 1523-24 to the Ahom Kingdom after a series of conflicts and the capital area ruled by the Chutia rulers became the administrative domain of the office of Sadia Khowa Gohain of the Ahom kingdom.

The Chutia kingdom was one among several rudimentary states (Ahom, Dimasa, Koch, Jaintia etc.) that emerged from tribal political formations in the region, between the 13th and the 16th century, after the fall of the Kamarupa kingdom. Among these, the Chutia state was the most advanced, with its rural industries, trade, surplus economy and advanced Sanskritisation. It is not exactly known as to the system of agriculture adopted by the Chutias, but it is believed that they were settled cultivators. After the Ahoms annexed the kingdom in 1523, the Chutia state was absorbed into the Ahom state — the nobility and the professional classes were given important positions in the Ahom officialdom and the land was resettled for wet rice cultivation.

Foundation and Polity

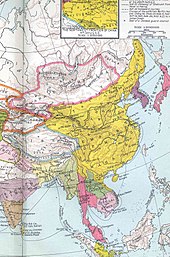

Chutia kingdom along with the Ahom kingdom, Tibet, Ming dynasty and other regional states in the year 1415.

Though there is no doubt on the Chutia polity, the origins of this kingdom is obscure. It is generally held that the Chutias established a state around Sadiya and contiguous areas in the 13th century before the advent of the Ahoms in 1228. Buranjis, the Ahom chronicles, mention the presence of the Chutia state, and a confrontation during the reign of Sutuphaa (1369-1379). The earliest Chutia king in the epigraphic records is Nandin or Nandisvara, from the later half of the 14th century, mentioned in a grant by his son Satyanarayana who nevertheless draws his royal lineage from Asuras. The mention of Satyanarayana as having the shape of his maternal uncle (which is also an indirect reference to the same Asura/Daitya lineage) may also constitute evidence of matrilineality of the Chutia ruling family, or that their system was not exclusively patrilineal. On the other hand, a later king Durlabhnarayana mentions that his grandfather Ratnanarayana (identified with Satyanarayana) was the king of Kamatapurawhich might indicate that the eastern region of Sadhaya was politically connected to the western region of Kamata. In these early inscriptions, the kings are said to be seated in Sadhyapuri, identified with the present-day Sadiya; which is why the kingdom is also called Sadiya. The Buranjis written in the Ahom language called the kingdom Tiora whereas those written in the Assamese language called it Chutia.

Brahmanical influence in the form of Vaishnavism reached the Chutia polity in the eastern extremity of present-day Assam during the late fourteenth century. Vaishnava brahmins created lineages for the rulers with references to Krishna legends but placed them lower in the Brahminical social hierarchy because of their autochthonous origins. Though asura lineage of the Chutia rulers have similarities with the Narakasura lineage created for the three Kamarupa dynasties, the precise historical connection is not clear. Although a majority of the brahmin donees of the royal grants were Vaishnavas, the rulers patronized the non-brahmanised Dikkaravasini as well. Dikkaravasini (also Tamresvari or Kesai-khaiti), was either a powerful tribal deity, or a Buddhist deity adopted for tribal worship. This deity, noticed in the 10th century Kalika Purana well before the establishment of the Chutia kingdom, continued to be presided by a Deori-Chutia priesthood well into the Ahom rule and outside brahminical influence.

The royal family traced its descent from the line of Viyutsva.

Spurious accounts

Unfortunately, there are many manuscript accounts of the origin and lineage that do not agree with each other or with the epigraphic records and therefore have no historical moorings. One such source is Chutiyar Rajar Vamsavali, first published in Orunodoi in 1850 and reprinted in Deodhai Asam Buranji. Historians consider this document to have been composed in the early 19th century—to legitimize the Matak kingdom around 1805—or after the end of Ahom rule in 1826. This document relates the legend of Birpal. Yet another Assamese document, retrieved by Ney Elias from Burmese sources, relates an alternative legend of Asambhinna. These different legends suggest that the genealogical claims of the Chutias have changed over time and that these are efforts to construct (and reconstruct) the past.

Rulers

Only a few recently compiled Buranjis provide the history of the Chutia kingdom; though some sections of these compilations are old, the sections that contain the list of Chutiya rulers cannot be traced to earlier than 19th century and scholars have shown great disdain for these accounts and legends.

Neog (1977) compiled a list of rulers based on epigraphic records based crucially on identifying the donor-ruler named Dharmanarayan, mentioned as the son of Satyanarayana in the Bormurtiya grant with the Dharmanarayan, the father of the donor-ruler Durlabhnarayana of the Chepakhowa grant. This effectively results in identifying Satyanarayana with Ratnanarayana.

| Name | Other names | Reign Period | Reign in Progress |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nandi | Nandisara or Nandisvara | late 14th century | |

| Satyanarayana | Ratnanarayana | late 14th century | 1392 |

| Lakshminarayana | Dharmanarayana or Mukta-dharmanaryana | early 15th century | 1392; 1401; 1442 |

| Durlabhnarayana | early 15th century | 1428 | |

| Pratyaksanarayana | |||

| Yasanarayana |

A late discovery of an inscription, published in a 2002 souvenir of the All Assam Chutiya Sanmilan seems to genealogically connect the last historically known king, Dhirnarayan with Neog’s list above.

| Name | Other names | Reign Period | Reign in progress |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yasamanarayana | |||

| Purandarnarayana | late 15th century | ||

| Dhirnarayana | early 16th century | 1522 |

Though it is accepted that the rule of the Chutia rulers ended in 1523-24, different sources give different accounts. The extant Ahom Buranji and the Deodhai Asam Buranji mention that in the final battles and the aftermath both the king and the heir-apparent were killed; whereas Ahom Buranji-Harakanta Barua mentions that the remnant of the royal family was deported to Pakariguri, Nagaon—a fact that is disputed by scholars.

Domain

The extent of the power of the kings of the Chutia kingdom is not known in detail. Nevertheless, it is estimated by most modern scholarship that Chutias held the areas on the north bank of Brahmaputra from Parshuram Kund (present-day Arunachal Pradesh) in the east and included the present districts of Lakhimpur, Dhemaji, Tinsukia and some parts of Dibrugarh in Assam. Between 1228 and 1253 when Sukaphaa, the founder of the Ahom kingdom, was searching for a place to settle in Upper Assam, he and his followers did not encounter any resistance from the Chutia state, implying that the Chutia state must have been of little significance till at least the mid 14th century, when the Ahom chronicles mention them for the first time. However, it is also known that the Ahoms themselves were a people with a precariously small territory and population, which may indicate this absence of serious interaction with the old settled people of the neighborhood until the 14th century. At its largest extent, the Chutia influence might have extended up to Viswanath in the present Darrang district of Assam , though the main control was confined to the river valleys of Subansiri, Brahmaputra, Lohit and Dihing and hardly extended to the hills even at its zenith.

Downfall

Some existing weaponry used by the Chutia kings

Chutia-Ahom conflicts (1512–1524)

Suhungmung, the Ahom king, followed an expansionist policy and annexed Habung and Panbari in either 1510 or 1512, which according to Swarnalata Baruah was ruled by Bhuyans while according to Amalendu Guha, it was a Chutia dependency. In 1513 a border conflict triggered the Chutia king Dhirnarayan to advance to Dikhowmukh and build a stockade of banana trees (Posola-garh). This fort was attacked by a force led by the Ahom king himself leading to a rout of the Chutia soldiers. In 1520 the Chutias again attacked the Ahom fort Mungkhrang and occupied it, but the Ahoms recovered it soon and erected an offensive fort on the banks of Dibru river. In 1523 the Chutia king attacked the fort at Dibru but was routed. The Ahom king and the nobles hotly pursued the retreating Chutia king who sued for peace. The peace overtures failed and the king finally fell to Ahom forces, bringing an end to the Chutia kingdom. Though some late manuscripts mention the fallen king as Nitipal (or Chandranarayan) extant records from the Buranjis such as the Ahom Buranji and the Deodhai Ahom Buranji doesn’t mention any names.

Aftermath

The Ahom kingdom took complete possession of the royal insignia and other assets of the erstwhile kingdom. The rest of the royal family was dispersed, and the nobles were disbanded and the territory was placed under the newly created office of the Sadiakhowa Gohain. Besides the material assets and territories, the Ahoms also took possession of the people according to their professions. Many of Brahmans, Kayasthas, Kalitas and Daivajnas (the caste Hindus), as well as the artisans such as bell-metal workers, goldsmiths, blacksmiths and others were moved to the Ahom capital and this movement greatly increased the admixture of the Chutia and Ahom populations. A sizeable section of the population was also displaced from their former lands and dispersed in other parts of Upper Assam.

After annexing the Chutia kingdom, offices of the Ahom kingdom, Thao-mung Mung-teu(Bhatialia Gohain) with headquarters at Habung (Lakhimpur), Thao-mung Ban-lung(Banlungia Gohain) at Banlung (Dhemaji), Thao-mung Mung-klang(Dihingia gohain) at Dihing (Dibrugarh, Majuli and northern Sibsagar), Chaolung Shulung at Tiphao (northern Dibrugarh) were created to administer the newly acquired regions.