The writing systems used in ancient Egypt were deciphered in the early nineteenth century through the work of several European scholars, especially Jean-François Champollion and Thomas Young. Ancient Egyptian forms of writing, which included the hieroglyphic, hieratic and demotic scripts, ceased to be understood in the fourth and fifth centuries AD, as the Coptic alphabet was increasingly used in their place. Later generations’ knowledge of the older scripts was based on the work of Greek and Roman authors whose understanding was faulty. It was thus widely believed that Egyptian scripts were exclusively ideographic, representing ideas rather than sounds, and even that hieroglyphs were an esoteric, mystical script rather than a means of recording a spoken language. Some attempts at decipherment by Islamic and European scholars in the Middle Ages and early modern times acknowledged the script might have a phonetic component, but perception of hieroglyphs as purely ideographic hampered efforts to understand them as late as the eighteenth century.

The Rosetta Stone, discovered in 1799 by members of Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaign in Egypt, bore a parallel text in hieroglyphic, demotic and Greek. It was hoped that the Egyptian text could be deciphered through its Greek translation, especially in combination with the evidence from the Coptic language, the last stage of the Egyptian language. Doing so proved difficult, despite halting progress made by Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy and Johan David Åkerblad. Young, building on their work, observed that demotic characters were derived from hieroglyphs and identified several of the phonetic signs in demotic. He also identified the meaning of many hieroglyphs, including phonetic glyphs in a cartouche containing the name of an Egyptian king of foreign origin, Ptolemy V. He was convinced, however, that phonetic hieroglyphs were used only in writing non-Egyptian words. In the early 1820s Champollion compared Ptolemy’s cartouche with others and realised the hieroglyphic script was a mixture of phonetic and ideographic elements. His claims were initially met with scepticism and with accusations that he had taken ideas from Young without giving credit, but they gradually gained acceptance. Champollion went on to roughly identify the meanings of most phonetic hieroglyphs and establish much of the grammar and vocabulary of ancient Egyptian. Young, meanwhile, largely deciphered demotic using the Rosetta Stone in combination with other Greek and demotic parallel texts.

Decipherment efforts languished after Young’s death in 1829 and Champollion’s in 1831, but in 1837 Karl Richard Lepsius pointed out that many hieroglyphs represented combinations of two or three sounds rather than one, thus correcting one of the most fundamental faults in Champollion’s work. Other scholars, such as Emmanuel de Rougé, refined the understanding of Egyptian enough that by the 1850s it was possible to fully translate ancient Egyptian texts. Combined with the decipherment of cuneiform at approximately the same time, their work opened up the once-inaccessible texts from the earliest stages of human history.

Egyptian scripts and their extinction

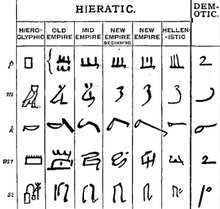

Table showing the evolution of hieroglyphic signs (left) through several stages of hieratic into demotic (right)

For most of its history ancient Egypt had two major writing systems. Hieroglyphs, a system of pictorial signs used mainly for formal texts, originated sometime around 3200 BC. Hieratic, a cursive system derived from hieroglyphs that was used mainly for writing on papyrus, was nearly as old. Beginning in the seventh century BC, a third script derived from hieratic, known today as demotic, emerged. It differed so greatly from its hieroglyphic ancestor that the relationship between the signs is difficult to recognise. Demotic became the most common system for writing the Egyptian language, and hieroglyphic and hieratic were thereafter mostly restricted to religious uses. In the fourth century BC, Egypt came to be ruled by the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty, and Greek and demotic were used side-by-side in Egypt under Ptolemaic rule and then that of the Roman Empire. Hieroglyphs became increasingly obscure, used mainly by Egyptian priests.

All three scripts contained a mix of phonetic signs, representing sounds in the spoken language, and ideographic signs, representing ideas. Phonetic signs included uniliteral, biliteral and triliteral signs, standing respectively for one, two or three sounds. Ideographic signs included logograms, representing whole words, and determinatives, which were used to specify the meaning of a word written with phonetic signs.

Many Greek and Roman authors wrote about these scripts, and many were aware that the Egyptians had two or three writing systems, but none whose works survived into later times fully understood how the scripts worked. Diodorus Siculus, in the first century BC, explicitly described hieroglyphs as an ideographic script, and most classical authors shared this assumption. Plutarch, in the first century AD, referred to 25 Egyptian letters, suggesting he might have been aware of the phonetic aspect of hieroglyphic or demotic, but his meaning is unclear. Around AD 200 Clement of Alexandriahinted that some signs were phonetic but concentrated on the signs’ metaphorical meanings. Plotinus, in the third century AD, claimed hieroglyphs did not represent words but a divinely inspired, fundamental insight into the nature of the objects they depicted. Ammianus Marcellinus in the fourth century AD copied another author’s translation of a hieroglyphic text on an obelisk, but the translation was too loose to be useful in understanding the principles of the writing system. The only extensive discussion of hieroglyphs to survive into modern times was the Hieroglyphica, a work probably written in the fourth century AD and attributed to a man named Horapollo. It discusses the meanings of individual hieroglyphs, though not how those signs were used to form phrases or sentences. Some of the meanings it describes are correct, but more are wrong, and all are misleadingly explained as allegories. For instance, Horapollo says an image of a goose means “son” because geese are said to love their children more than other animals. In fact the goose hieroglyph was used because the Egyptian words for “goose” and “son” incorporated the same consonants.

Both hieroglyphic and demotic began to disappear in the third century AD. The temple-based priesthoods died out and Egypt was gradually converted to Christianity, and because Egyptian Christians wrote in the Greek-derived Coptic alphabet, it came to supplant demotic. The last hieroglyphic text was written by priests at the Temple of Isis at Philae in AD 394, and the last demotic text was inscribed there in AD 452. Most of history before the first millennium BC was recorded in Egyptian scripts or in cuneiform, the writing system of Mesopotamia. With the loss of knowledge of both these scripts, the only records of the distant past were in limited and distorted sources. The major Egyptian example of such a source was Aegyptiaca, a history of the country written by an Egyptian priest named Manetho in the third century BC. The original text was lost, and it survived only in summaries and quotations by Roman authors.

The Coptic language, the last form of the Egyptian language, continued to be spoken by most Egyptians well after the Arab conquest of Egypt in AD 642, but it gradually lost ground to Arabic. Coptic began to die out in the twelfth century, and thereafter it survived mainly as the liturgical language of the Coptic Church.

Early efforts

Medieval Islamic world

Ibn Wahshiyya’s attempted translation of hieroglyphs

Arab scholars were aware of the connection between Coptic and the ancient Egyptian language, and Coptic monks in Islamic times were sometimes believed to understand the ancient scripts. Several Arab scholars in the seventh through fourteenth centuries, including Jabir ibn Hayyan and Ayub ibn Maslama, are said to have understood hieroglyphs, although because their works on the subject have not survived these claims cannot be tested. Dhul-Nun al-Misri and Ibn Wahshiyya, in the ninth and tenth centuries, wrote treatises containing dozens of scripts known in the Islamic world, including hieroglyphs, with tables listing their meanings. In the thirteenth or fourteenth century, Abu al-Qasim al-Iraqi copied an ancient Egyptian text and assigned phonetic values to several hieroglyphs. The Egyptologist Okasha El-Daly has argued that the tables of hieroglyphs in the works of Ibn Wahshiyya and Abu al-Qasim correctly identified the meaning of many of the signs. Other scholars have been sceptical of Ibn Wahshiyya’s claims to understand the scripts he wrote about, and Tara Stephan, a scholar of the medieval Islamic world, says El-Daly “vastly overemphasizes Ibn Waḥshiyya’s accuracy”. Ibn Wahshiyya and Abu al-Qasim did recognise that hieroglyphs could function phonetically as well as symbolically, a point that would not be acknowledged in Europe for centuries.

Fifteenth through seventeenth centuries

A page from Athanasius Kircher’s Obeliscus Pamphilius (1650), with fanciful translations given for the figures and hieroglyphs on an obelisk in Rome

During the Renaissance Europeans became interested in hieroglyphs, beginning around 1422 when Cristoforo Buondelmonti discovered a copy of Horapollo’s Hieroglyphica in Greece and brought it to the attention of antiquarians such as Niccolò de’ Niccoli and Poggio Bracciolini. Poggio recognised that there were hieroglyphic texts on obelisks and other Egyptian artefacts imported to Europe in Roman times, but the antiquarians did not attempt to decipher these texts. Influenced by Horapollo and Plotinus, they saw hieroglyphs as a universal, image-based form of communication, not a means of recording a spoken language. From this belief sprang a Renaissance artistic tradition of using obscure symbolism loosely based on the imagery described in Horapollo, pioneered by Francesco Colonna’s 1499 book Hypnerotomachia Poliphili.

Europeans were ignorant of Coptic as well. Scholars sometimes obtained Coptic manuscripts, but in the sixteenth century, when they began to seriously study the language, the ability to read it may have been limited to Coptic monks, and no Europeans of the time had the opportunity to learn from one of these monks, who did not travel outside Egypt. Scholars were also unsure whether Coptic was descended from the language of the ancient Egyptians; many thought it was instead related to other languages of the ancient Near East.

The first European to make sense of Coptic was a Jesuit and polymath, Athanasius Kircher, in the mid-seventeenth century. Basing his work on Arabic grammars and dictionaries of Coptic acquired in Egypt by an Italian traveller, Pietro Della Valle, Kircher produced flawed but pioneering translations and grammars of the language in the 1630s and 1640s. He guessed that Coptic was derived from the language of the ancient Egyptians, and his work on the subject was preparation for his ultimate goal, decipherment of the hieroglyphic script.

According to the standard biographical dictionary of Egyptology, “Kircher has become, perhaps unfairly, the symbol of all that is absurd and fantastic in the story of the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs”. Kircher thought the Egyptians had believed in an ancient theological tradition that preceded and foreshadowed Christianity, and he hoped to understand this tradition through hieroglyphs. Like his Renaissance predecessors, he believed hieroglyphs represented an abstract form of communication rather than a language. To translate such a system of communication in a self-consistent way was impossible. Therefore, in his works on hieroglyphs, such as Oedipus Aegyptiacus (1652–1655), Kircher proceeded by guesswork based on his understanding of ancient Egyptian beliefs, derived from the Coptic texts he had read and from ancient texts that he thought contained traditions derived from Egypt. His translations turned short texts containing only a few hieroglyphic characters into lengthy sentences of esoteric ideas. Unlike earlier European scholars, Kircher did realise that hieroglyphs could function phonetically, though he considered this function a late development. He also recognised one hieroglyph, 𓈗, as representing water and thus standing phonetically for the Coptic word for water, mu, as well as the m sound. He became the first European to correctly identify a phonetic value for a hieroglyph.

Although Kircher’s basic assumptions were shared by his contemporaries, most scholars rejected or even ridiculed his translations. Nevertheless, his argument that Coptic was derived from the ancient Egyptian language was widely accepted.

Eighteenth century

Page from Recueil d’antiquités égyptiennes by Anne Claude de Caylus, 1752, comparing hieroglyphs to similar signs in other Egyptian scripts

Hardly anyone attempted to decipher hieroglyphs for decades after Kircher’s last works on the subject, although some contributed suggestions about the script that ultimately proved correct. William Warburton’s religious treatise The Divine Legation of Moses, published from 1738 to 1741, included a long digression on hieroglyphs and the evolution of writing. It argued that hieroglyphs were not invented to encode religious secrets but for practical purposes, like any other writing system, and that the phonetic Egyptian script mentioned by Clement of Alexandria was derived from them. Warburton’s approach, though purely theoretical, created the framework for understanding hieroglyphs that would dominate scholarship for the rest of the century.

Europeans’ contact with Egypt increased during the eighteenth century. More of them visited the country and saw its ancient inscriptions firsthand, and as they collected antiquities, the number of texts available for study increased. Jean-Pierre Rigord became the first European to identify a non-hieroglyphic ancient Egyptian text in 1704, and Bernard de Montfaucon published a large collection of such texts in 1724. Anne Claude de Caylus collected and published a large number of Egyptian inscriptions from 1752 to 1767, assisted by Jean-Jacques Barthélemy. Their work noted that non-hieroglyphic Egyptian scripts seemed to contain signs derived from hieroglyphs. Barthélemy also pointed out the oval rings, later to be known as cartouches, that enclosed small groups of signs in many hieroglyphic texts, and in 1762 he suggested that cartouches contained the names of kings or gods. Carsten Niebuhr, who visited Egypt in the 1760s, produced the first systematic, though incomplete, list of distinct hieroglyphic signs. He also pointed out the distinction between hieroglyphic text and the illustrations that accompanied it, whereas earlier scholars had confused the two. Joseph de Guignes, one of several scholars of the time who speculated that China had some historical connection to ancient Egypt, believed Chinese writing was an offshoot of hieroglyphs. In 1785 he r