Israel, officially known as the State of Israel, is a country in Western Asia, located on the southeastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea and the northern shore of the Red Sea. It has land borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the northeast, Jordan on the east, the Palestinian territories of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip to the east and west, respectively, and Egypt to the southwest. Israel’s economic and technological center is Tel Aviv, while its seat of government and proclaimed capital is Jerusalem, although international recognition of the state’s sovereignty over Jerusalem is limited.

Israel has evidence of the earliest migration of hominids out of Africa. Canaanite tribes are archaeologically attested since the Middle Bronze Age, while the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah emerged during the Iron Age. The Neo-Assyrian Empire destroyed Israel around 720 BCE. Judah was later conquered by the Babylonian, Persian and Hellenistic empires and had existed as Jewish autonomous provinces. The successful Maccabean Revolt led to an independent Hasmonean kingdom by 110 BCE, which in 63 BCE however became a client state of the Roman Republic that subsequently installed the Herodian dynasty in 37 BCE, and in 6 CE created the Roman province of Judea. Judea lasted as a Roman province until the failed Jewish revolts resulted in widespread destruction, the expulsion of the Jewish population and the renaming of the region from Iudaea to Syria Palaestina. Jewish presence in the region has persisted to a certain extent over the centuries. In the 7th century CE, the Levant was taken from the Byzantine Empire by the Arabs and remained in Muslim control until the First Crusade of 1099, followed by the Ayyubid conquest of 1187. The Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt extended its control over the Levant in the 13th century until its defeat by the Ottoman Empire in 1517. During the 19th century, national awakening among Jews led to the establishment of the Zionist movement followed by immigration to Palestine.

During the first half of the 20th century, the land was controlled as a mandate of the British Empire from 1920-1948, having been ceded by the Ottomans at the end of the First World War. Not long after, the Second World War saw the mandate bombed heavily and Yishuv Jews serve for the Allies, after the British agreed to supply arms and form a Jewish Brigade in 1944. Among growing tension and the British eager to appease both Arab and Jewish propositions, the United Nations (UN) adopted a Partition Plan for Palestine in 1947 recommending the creation of independent Arab and Jewish states and an internationalized Jerusalem. The plan was accepted by the Jewish Agency, and rejected by Arab leaders. The following year, the Jewish Agency declared the independence of the State of Israel, and the subsequent 1948 Arab–Israeli War saw Israel’s establishment over most of the former Mandate territory, while the West Bank and Gaza were held by neighboring Arab states. Israel has since fought several wars with Arab countries, and since the Six-Day War in June 1967 held occupied territories including the West Bank, Golan Heights and the Gaza Strip (still considered occupied after the 2005 disengagement, although some legal experts dispute this claim). Subsequent legislative acts have resulted in the full application of Israeli law within the Golan Heights and East Jerusalem, as well as its partial application in the West Bank via “pipelining” into Israeli settlements. Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories is internationally considered to be the world’s longest military occupation in modern times. Efforts to resolve the Israeli–Palestinian conflict have not resulted in a final peace agreement, while Israel has signed peace treaties with both Egypt and Jordan.

In its Basic Laws, Israel defines itself as a Jewish and democratic state and the nation state of the Jewish people. The country is a liberal democracy with a parliamentary system, proportional representation, and universal suffrage. The prime minister is head of government and the Knesset is the legislature. With a population of around 9 million as of 2019, Israel is a developed country and an OECD member. It has the world’s 31st-largest economy by nominal GDP, and is the most developed country currently in conflict. It has the highest standard of living in the Middle East, and ranks among the world’s top countries by percentage of citizens with military training, percentage of citizens holding a tertiary education degree, research and development spending by GDP percentage, women’s safety, life expectancy, innovativeness, and happiness.

Etymology

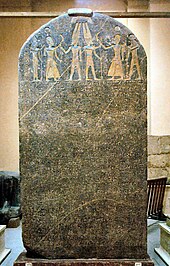

The Merneptah Stele (13th century BCE). The majority of biblical archeologists translate a set of hieroglyphs as “Israel,” the first instance of the name in the record.

Under British Mandate (1920–1948), the whole region was known as Palestine (Hebrew: פלשתינה , lit. ‘Palestine ‘). Upon independence in 1948, the country formally adopted the name ‘State of Israel’ (Hebrew: מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, ![]() Medīnat Yisrā’el ; Arabic: دَوْلَة إِسْرَائِيل, Dawlat Isrāʼīl, ) after other proposed historical and religious names including Eretz Israel (‘the Land of Israel’), Ever (from ancestor Eber), Zion, and Judea, were considered but rejected, while the name ‘Israel’ was suggested by Ben-Gurion and passed by a vote of 6–3. In the early weeks of independence, the government chose the term “Israeli” to denote a citizen of Israel, with the formal announcement made by Minister of Foreign Affairs Moshe Sharett.

Medīnat Yisrā’el ; Arabic: دَوْلَة إِسْرَائِيل, Dawlat Isrāʼīl, ) after other proposed historical and religious names including Eretz Israel (‘the Land of Israel’), Ever (from ancestor Eber), Zion, and Judea, were considered but rejected, while the name ‘Israel’ was suggested by Ben-Gurion and passed by a vote of 6–3. In the early weeks of independence, the government chose the term “Israeli” to denote a citizen of Israel, with the formal announcement made by Minister of Foreign Affairs Moshe Sharett.

The names Land of Israel and Children of Israel have historically been used to refer to the biblical Kingdom of Israel and the entire Jewish people respectively. The name ‘Israel’ (Hebrew: Yisraʾel, Isrāʾīl; Septuagint Greek: Ἰσραήλ, Israēl, ‘El (God) persists/rules’, though after Hosea 12:4 often interpreted as ‘struggle with God’) in these phrases refers to the patriarch Jacob who, according to the Hebrew Bible, was given the name after he successfully wrestled with the angel of the Lord. Jacob’s twelve sons became the ancestors of the Israelites, also known as the Twelve Tribes of Israel or Children of Israel. Jacob and his sons had lived in Canaan but were forced by famine to go into Egypt for four generations, lasting 430 years, until Moses, a great-great grandson of Jacob, led the Israelites back into Canaan during the “Exodus”. The earliest known archaeological artifact to mention the word “Israel” as a collective is the Merneptah Stele of ancient Egypt (dated to the late 13th century BCE).

The area is also known as the Holy Land, being holy for all Abrahamic religions including Judaism, Christianity, Islam and the Baháʼí Faith. Through the centuries, the territory was known by a variety of other names, including Canaan, Djahy, Samaria, Judea, Yehud, Iudaea, Syria Palaestina and Southern Syria.

History

Prehistory

The oldest evidence of early humans in the territory of modern Israel, dating to 1.5 million years ago, was found in Ubeidiya near the Sea of Galilee. Other notable Paleolithic sites include the caves Tabun, Qesem and Manot. The oldest fossils of anatomically modern humans found outside Africa are the Skhul and Qafzeh hominins, who lived in the area that is now northern Israel 120,000 years ago. Around 10th millennium BCE, the Natufian culture existed in the area.

Antiquity

The Large Stone Structure, archaeological site in Jerusalem

The early history of the territory is unclear.:104 Modern archaeology has largely discarded the historicity of the narrative in the Torah concerning the patriarchs, The Exodus, and the conquest of Canaan described in the Book of Joshua, and instead views the narrative as constituting the Israelites’ national myth. During the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 BCE), large parts of Canaan formed vassal states paying tribute to the New Kingdom of Egypt, whose administrative headquarters lay in Gaza. Ancestors of the Israelites are thought to have included ancient Semitic-speaking peoples native to this area.:78–79 The Israelites and their culture, according to the modern archaeological account, did not overtake the region by force, but instead branched out of these Canaanite peoples and their cultures through the development of a distinct monolatristic—and later monotheistic—religion centered on Yahweh. The archaeological evidence indicates a society of village-like centres, but with more limited resources and a small population. Villages had populations of up to 300 or 400, which lived by farming and herding, and were largely self-sufficient; economic interchange was prevalent. Writing was known and available for recording, even in small sites.

Map of Israel and Judah in the 9th century BCE

While it is unclear if there was ever a United Monarchy, there is well-accepted archeological evidence referring to “Israel” in the Merneptah Stele which dates to about 1200 BCE; and the Canaanites are archaeologically attested in the Middle Bronze Age (2100–1550 BCE). There is debate about the earliest existence of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah and their extent and power, but historians and archaeologists agree that a Kingdom of Israel existed by ca. 900 BCE:169–195 and that a Kingdom of Judah existed by ca. 700 BCE. The Kingdom of Israel was destroyed around 720 BCE, when it was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

In 586 BCE, King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon conquered Judah. According to the Hebrew Bible, he destroyed Solomon’s Temple and exiled the Jews to Babylon. The defeat was also recorded in the Babylonian Chronicles. The Babylonian exile ended around 538 BCE under the rule of the Medo-Persian Cyrus the Great after he captured Babylon. The Second Temple was constructed around 520 BCE. As part of the Persian Empire, the former Kingdom of Judah became the province of Judah (Yehud Medinata) with different borders, covering a smaller territory. The population of the province was greatly reduced from that of the kingdom, archaeological surveys showing a population of around 30,000 people in the 5th to 4th centuries BCE.:308

Classical period

Portion of the Temple Scroll, one of the Dead Sea Scrolls, written during the Second Temple period

With successive Persian rule, the autonomous province Yehud Medinata was gradually developing back into urban society, largely dominated by Judeans. The Greek conquests largely skipped the region without any resistance or interest. Incorporated into the Ptolemaic and finally the Seleucid empires, the southern Levant was heavily hellenized, building the tensions between Judeans and Greeks. The conflict erupted in 167 BCE with the Maccabean Revolt, which succeeded in establishing an independent Hasmonean Kingdom in Judah, which later expanded over much of modern Israel, as the Seleucids gradually lost control in the region.

The Roman Republic invaded the region in 63 BCE, first taking control of Syria, and then intervening in the Hasmonean Civil War. The struggle between pro-Roman and pro-Parthian factions in Judea eventually led to the installation of Herod the Great and consolidation of the Herodian kingdom as a vassal Judean state of Rome. With the decline of the Herodian dynasty, Judea, transformed into a Roman province, became the site of a violent struggle of Jews against Romans, culminating in the Jewish–Roman wars, ending in wide-scale destruction, expulsions, genocide, and enslavement of masses of Jewish captives. An estimated 1,356,460 Jews were killed as a result of the First Jewish Revolt; the Second Jewish Revolt (115–117) led to the death of more than 200,000 Jews; and the Third Jewish Revolt (132–136) resulted in the death of 580,000 Jewish soldiers.

Jewish presence in the region significantly dwindled after the failure of the Bar Kokhba revolt against the Roman Empire in 132 CE. Nevertheless, there was a continuous small Jewish presence and Galilee became its religious center. The Mishnah and part of the Talmud, central Jewish texts, were composed during the 2nd to 4th centuries CE in Tiberias and Jerusalem. The region came to be populated predominantly by Greco-Romans on the coast and Samaritans in the hill-country. Christianity was gradually evolving over Roman Paganism, when the area stood under Byzantine rule. Through the 5th and 6th centuries, the dramatic events of the repeated Samaritan revolts reshaped the land, with massive destruction to Byzantine Christian and Samaritan societies and a resulting decrease of the population. After the Persian conquest and the installation of a short-lived Jewish Commonwealth in 614 CE, the Byzantine Empire reconquered the country in 628.

Middle Ages and modern history

Kfar Bar’am, an ancient Jewish village, abandoned some time between the 7th–13th centuries CE.

In 634–641 CE, the region, including Jerusalem, was conquered by the Arabs who had recently adopted Islam. Control of the region transferred between the Rashidun Caliphs, Umayyads, Abbasids, Fatimids, Seljuks, Crusaders, and Ayyubids throughout the next three centuries.

During the siege of Jerusalem by the First Crusade in 1099, the Jewish inhabitants of the city fought side by side with the Fatimid garrison and the Muslim population who tried in vain to defend the city against the Crusaders. When the city fell, around 60,000 people were massacred, including 6,000 Jews seeking refuge in a synagogue. At this time, a full thousand years after the fall of the Jewish state, there were Jewish communities all over the country. Fifty of them are known and include Jerusalem, Tiberias, Ramleh, Ashkelon, Caesarea, and Gaza. According to Albert of Aachen, the Jewish residents of Haifa were the main fighting force of the city, and “mixed with Saracen troops”, they fought bravely for close to a month until forced into retreat by the Crusader fleet and land army.

In 1165, Maimonides visited Jerusalem and prayed on the Temple Mount, in the “great, holy house.” In 1141, the Spanish-Jewish poet Yehuda Halevi issued a call for Jews to migrate to the Land of Israel, a journey he undertook himself. In 1187, Sultan Saladin, founder of the Ayyubid dynasty, defeated the Crusaders in the Battle of Hattin and subsequently captured Jerusalem and almost all of Palestine. In time, Saladin issued a proclamation inviting Jews to return and settle in Jerusalem, and according to Judah al-Harizi, they did: “From the day the Arabs took Jerusalem, the Israelites inhabited it.” Al-Harizi compared Saladin’s decree allowing Jews to re-establish themselves in Jerusalem to the one issued by the Persian king Cyrus the Great over 1,600 years earlier.

The 13th-century Ramban Synagogue in Jerusalem

In 1211, the Jewish community in the country was strengthened by the arrival of a group headed by over 300 rabbis from France and England, among them Rabbi Samson ben Abraham of Sens. Nachmanides (Ramban), the 13th-century Spanish rabbi and recognised leader of Jewry, greatly praised the Land of Israel and viewed its settlement as a positive commandment incumbent on all Jews. He wrote “If the gentiles wish to make peace, we shall make peace and leave them on clear terms; but as for the land, we shall not leave it in their hands, nor in the hands of any nation, not in any generation.”

In 1260, control passed to the Mamluk sultans of Egypt. The country was located between the two centres of Mamluk power, Cairo and Damascus, and only saw some development along the postal road connecting the two cities. Jerusalem, although left without the protection of any city walls since 1219, also saw a flurry of new construction projects centred around the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound on the Temple Mount. In 1266, the Mamluk Sultan Baybars converted the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron into an exclusive Islamic sanctuary and banned Christians and Jews from entering, who previously had been able to enter it for a fee. The ban remained in place until Israel took control of the building in 1967.

Jews at the Western Wall, the 1870s

In 1470, Isaac b. Meir Latif arrived from Italy and counted 150 Jewish families in Jerusalem. Thanks to Joseph Saragossi who had arrived in the closing years of the 15th century, Safed and its environs had developed into the largest concentration of Jews in Palestine. With the help of the Sephardic immigration from Spain, the Jewish population had increased to 10,000 by the early 16th century.

In 1516, the region was conquered by the Ottoman Empire; it remained under Turkish rule until the end of the First World War, when Britain defeated the Ottoman forces and set up a military administration across the former Ottoman Syria. In 1660, a Druze revolt led to the destruction of Safed and Tiberias. In the late 18th century, local Arab Sheikh Zahir al-Umar created a de facto independent Emirate in the Galilee. Ottoman attempts to subdue the Sheikh failed, but after Zahir’s death the Ottomans regained control of the area. In 1799 governor Jazzar Pasha successfully repelled an assault on Acre by troops of Napoleon, prompting the French to abandon the Syrian campaign. In 1834 a revolt by Palestinian Arab peasants broke out against Egyptian conscription and taxation policies under Muhammad Ali. Although the revolt was suppressed, Muhammad Ali’s army retreated and Ottoman rule was restored with British support in 1840. Shortly after, the Tanzimat reforms were implemented across the Ottoman Empire. In 1920, after the Allies conquered the Levant during World War I, the territory was divided between Britain and France under the mandate system, and the British-administered area which included modern day Israel was named Mandatory Palestine.

Zionism and British Mandate

Theodor Herzl, visionary of the Jewish state

Since the existence of the earliest Jewish diaspora, many Jews have aspired to return to “Zion” and the “Land of Israel”, though the amount of effort that should be spent towards such an aim was a matter of dispute. The hopes and yearnings of Jews living in exile are an important theme of the Jewish belief system. After the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, some communities settled in Palestine. During the 16th century, Jewish communities struck roots in the Four Holy Cities—Jerusalem, Tiberias, Hebron, and Safed—and in 1697, Rabbi Yehuda Hachasid led a group of 1,500 Jews to Jerusalem. In the second half of the 18th century, Eastern European opponents of Hasidism, known as the Perushim, settled in Palestine.

Theodor Herzl (1896). – via Wikisource.

The first wave of modern Jewish migration to Ottoman-ruled Palestine, known as the First Aliyah, began in 1881, as Jews fled pogroms in Eastern Europe. The First Aliyah laid the cornerstone for widespread Jewish settlement in Palestine. From 1881 to 1903, the Jews had established dozens of settlements and purchased about 350,000 dunams of land. At the same time, the revival of the Hebrew language began among Jews in Palestine, spurred on largely by Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, a Russian-born Jew who had settled in Jerusalem in 1881. Jews were encouraged to speak Hebrew in the place of other languages, a Hebrew school system began to emerge, and new words were coined or borrowed from other languages for modern inventions and concepts. As a result, Hebrew gradually became the predominant language of the Jewish community of Palestine, which until then had been divided into different linguistic communities that primarily used Hebrew for religious purposes and as a means of communication between Jews with different native languages.

Although the Zionist movement already existed in practice, Austro-Hungarian journalist Theodor Herzl is credited with founding political Zionism, a movement that sought to establish a Jewish state in the Land of Israel, thus offering a solution to the so-called Jewish question of the European states, in conformity with the goals and achievements of other national projects of the time. In 1896, Herzl published Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State), offering his vision of a future Jewish state; the following year he presided over the First Zionist Congress. The Second Aliyah (1904–14), began after the Kishinev pogrom; some 40,000 Jews settled in Palestine, although nearly half of them left eventually. Both the first and second waves of migrants were mainly Orthodox Jews, although the Second Aliyah included socialist groups who established the kibbutz movement. Though the immigrants of the Second Aliyah largely sought to create communal agricultural settlements, the period also saw the establishment of Tel Aviv in 1909 as the “first Hebrew city.” This period also saw the appearance of Jewish armed self-defense organizations as a means of defense for Jewish settlements. The first such organization was Bar-Giora, a small secret guard founded in 1907. Two years later, larger Hashomer organization was founded as its replacement. During World War I, British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour sent the Balfour Declaration to Baron Rothschild (Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild), a leader of the British Jewish community, that stated that Britain intended for the creation of a Jewish “national home” in Palestine.

In 1918, the Jewish Legion, a group primarily of Zionist volunteers, assisted in the British conquest of Palestine. Arab opposition to British rule and Jewish immigration led to the 1920 Palestine riots and the formation of a Jewish militia known as the Haganah (meaning “The Defense” in Hebrew) in 1920 as an outgrowth of Hashomer, from which the Irgun and Lehi, or the Stern Gang, paramilitary groups later split off. In 1922, the League of Nations granted Britain the Mandate for Palestine under terms which included the Balfour Declaration with its promise to the Jews, and with similar provisions regarding the Arab Palestinians. The population of the area at this time was predominantly Arab and Muslim, with Jews accounting for about 11%, and Arab Christians about 9.5% of the population.

The Third (1919–23) and Fourth Aliyahs (1924–29) brought an additional 100,000 Jews to Palestine. The rise of Nazism and the increasing persecution of Jews in 1930s Europe led to the Fifth Aliyah, with an influx of a quarter of a million Jews. This was a major cause of the Arab revolt of 1936–39, which was launched as a reaction to continued Jewish immigration and land purchases. Several hundred Jews and British security personnel were killed, while the British Mandate authorities alongside the Zionist militias of the Haganah and Irgun killed 5,032 Arabs and wounded 14,760, resulting in over ten percent of the adult male Palestinian Arab population killed, wounded, imprisoned or exiled. The British introduced restrictions on Jewish immigration to Palestine with the White Paper of 1939. With countries around the world turning away Jewish refugees fleeing the Holocaust, a clandestine movement known as Aliyah Bet was organized to bring Jews to Palestine. By the end of World War II, the Jewish population of Palestine had increased to 31% of the total population.

After World War II

UN Map, “Palestine plan of partition with economic union”

After World War II, the UK found itself facing a Jewish guerrilla campaign over Jewish immigration limits, as well as continued conflict with the Arab community over limit levels. The Haganah joined Irgun and Lehi in an armed struggle against British rule. At the same time, hundreds of thousands of Jewish Holocaust survivors and refugees sought a new life far from their destroyed communities in Europe. The Haganah attempted to bring these refugees to Palestine in a program called Aliyah Bet in which tens of thousands of Jewish refugees attempted to enter Palestine by ship. Most of the ships were intercepted by the Royal Navy and the refugees rounded up and placed in detention camps in Atlit and Cyprus by the British.

On 22 July 1946, Irgun attacked the British administrative headquarters for Palestine, which was housed in the southern wing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem. A total of 91 people of various nationalities were killed and 46 were injured. The hotel was the site of the Secretariat of the Government of Palestine and the Headquarters of the British Armed Forces in Mandatory Palestine and Transjordan. The attack initially had the approval of the Haganah. It was conceived as a response to Operation Agatha (a series of widespread raids, including one on the Jewish Agency, conducted by the British authorities) and was the deadliest directed at the British during the Mandate era. The Jewish insurgency continued throughout the rest of 1946 and 1947 despite repressive efforts by the British military and Palestine Police Force to stop it. British efforts to mediate a negotiated solution with Jewish and Arab representatives also failed as the Jews were unwilling to accept any solution that did not involve a Jewish state and suggested a partition of Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, while the Arabs were adamant that a Jewish state in any part of Palestine was unacceptable and that the only solution was a unified Palestine under Arab rule. In February 1947, the British referred the Palestine issue to the newly formed United Nations. On 15 May 1947, the General Assembly of the United Nations resolved that the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine be created “to prepare for consideration at the next regular session of the Assembly a report on the question of Palestine.” In the Report of the Committee dated 3 September 1947 to the General Assembly, the majority of the Committee in Chapter VI proposed a plan to replace the British Mandate with “an independent Arab State, an independent Jewish State, and the City of Jerusalem the last to be under an International Trusteeship System.” Meanwhile, the Jewish insurgency continued and peaked in July 1947, with a series of widespread guerrilla raids culminating in the sergeants affair. After three Irgun fighters had been sentenced to death for their role in the Acre Prison break, a May 1947 Irgun raid on Acre Prison in which 27 Irgun and Lehi militants were freed, the Irgun captured two British sergeants and held them hostage, threatening to kill them if the three men were executed. When the British carried out the executions, the Irgun responded by killing the two hostages and hanged their bodies from eucalyptus trees, booby-trapping one of them with a mine which injured a British officer as he cut the body down. The hangings caused widespread outrage in Britain and were a major factor in the consensus forming in Britain that it was time to evacuate Palestine.

In September 1947, the British cabinet decided that the Mandate was no longer tenable, and to evacuate Palestine. According to Colonial Secretary Arthur Creech Jones, four major factors led to the decision to evacuate Palestine: the inflexibility of Jewish and Arab negotiators who were unwilling to compromise on their core positions over the question of a Jewish state in Palestine, the economic pressure that stationing a large garrison in Palestine to deal with the Jewish insurgency and the possibility of a wider Jewish rebellion and the possibility of an Arab rebellion put on a British economy already strained by World War II, the “deadly blow to British patience and pride” caused by the hangings of the sergeants, and the mounting criticism the government faced in failing to find a new policy for Palestine in place of the White Paper of 1939.

On 29 November 1947, the General Assembly adopted Resolution 181 (II) recommending the adoption and implementation of the Plan of Partition with Economic Union. The plan attached to the resolution was essentially that proposed by the majority of the Committee in the report of 3 September. The Jewish Agency, which was the recognized representative of the Jewish community, accepted the plan. The Arab League and Arab Higher Committee of Palestine rejected it, and indicated that they would reject any other plan of partition. On the following day, 1 December 1947, the Arab Higher Committee proclaimed a three-day strike, and riots broke out in Jerusalem. The situation spiralled into a civil war; just two weeks after the UN vote, Colonial Secretary Arthur Creech Jones announced that the British Mandate would end on 15 May 1948, at which point the British would evacuate. As Arab militias and gangs attacked Jewish areas, they were faced mainly by the Haganah, as well as the smaller Irgun and Lehi. In April 1948, the Haganah moved onto the offensive. During this period 250,000 Palestinian Arabs fled or were expelled, due to a number of factors.

On 14 May 1948, the day before the expiration of the British Mandate, David Ben-Gurion, the head of the Jewish Agency, declared “the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz-Israel, to be known as the State of Israel.” The only reference in the text of the Declaration to the borders of the new state is the use of the term Eretz-Israel (“Land of Israel”). The following day, the armies of four Arab countries—Egypt, Syria, Transjordan and Iraq—entered what had been British Mandatory Palestine, launching the 1948 Arab–Israeli War; contingents from Yemen, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and Sudan joined the war. The apparent purpose of the invasion was to prevent the establishment of the Jewish state at inception, and some Arab leaders talked about driving the Jews into the sea. According to Benny Morris, Jews felt that the invading Arab armies aimed to slaughter the Jews. The Arab league stated that the invasion was to restore law and order and to prevent further bloodshed.

After a year of fighting, a ceasefire was declared and temporary borders, known as the Green Line, were established. Jordan annexed what became known as the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and Egypt occupied the Gaza Strip. The UN estimated that more than 700,000 Palestinians were expelled by or fled from advancing Israeli forces during the conflict—what would become known in Arabic as the Nakba (“catastrophe”). Some 156,000 remained and became Arab citizens of Israel.

Early years of the State of Israel

Israel was admitted as a member of the UN by majority vote on 11 May 1949. Both Israel and Jordan were genuinely interested in a peace agreement but the British acted as a brake on the Jordanian effort in order to avoid damaging British interests in Egypt. In the early years of the state, the Labor Zionist movement led by Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion dominated Israeli politics. The kibbutzim, or collective farming communities, played a pivotal role in establishing the new state.

Immigration to Israel during the late 1940s and early 1950s was aided by the Israeli Immigration Department and the non-government sponsored Mossad LeAliyah Bet (lit. “Institute for Immigration B”) which organized illegal and clandestine immigration. Both groups facilitated regular immigration logistics like arranging transportation, but the latter also engaged in clandestine operations in countries, particularly in the Middle East and Eastern Europe, where the lives of Jews were believed to be in danger and exit from those places was difficult. Mossad LeAliyah Bet was disbanded in 1953. The immigration was in accordance with the One Million Plan. The immigrants came for differing reasons: some held Zionist beliefs or came for the promise of a better life in Israel, while others moved to escape persecution or were expelled.

An influx of Holocaust survivors and Jews from Arab and Muslim countries to Israel during the first three years increased the number of Jews from 700,000 to 1,400,000. By 1958, the population of Israel rose to two million. Between 1948 and 1970, approximately 1,150,000 Jewish refugees relocated to Israel. Some new immigrants arrived as refugees with no possessions and were housed in temporary camps known as ma’abarot; by 1952, over 200,000 people were living in these tent cities. Jews of European background were often treated more favorably than Jews from Middle Eastern and North African countries—housing units reserved for the latter were often re-designated for the former, with the result that Jews newly arrived from Arab lands generally ended up staying in transit camps for longer. During this period, food, clothes and furniture had to be rationed in what became known as the austerity period. The need to solve the crisis led Ben-Gurion to sign a reparations agreement with West Germany that triggered mass protests by Jews angered at the idea that Israel could accept monetary compensation for the Holocaust.

U.S. newsreel on the trial of Adolf Eichmann

During the 1950s, Israel was frequently attacked by Palestinian fedayeen, nearly always against civilians, mainly from the Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip, leading to several Israeli reprisal operations. In 1956, the United Kingdom and France aimed at regaining control of the Suez Canal, which the Egyptians had nationalized. The continued blockade of the Suez Canal and Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping, together with the growing amount of Fedayeen attacks against Israel’s southern population, and recent Arab grave and threatening statements, prompted Israel to attack Egypt. Israel joined a secret alliance with the United Kingdom and France and overran the Sinai Peninsula but was pressured to withdraw by the UN in return for guarantees of Israeli shipping rights in the Red Sea via the Straits of Tiran and the Canal. The war, known as the Suez Crisis, resulted in significant reduction of Israeli border infiltration. In the early 1960s, Israel captured Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in Argentina and brought him to Israel for trial. The trial had a major impact on public awareness of the Holocaust. Eichmann remains the only person executed in Israel by conviction in an Israeli civilian court. During the spring and summer of 1963 Israel was engaged in a, now declassified diplomatic standoff with the United States due to the Israeli nuclear program.

Territory held by Israel:

The Sinai Peninsula was returned to Egypt in 1982.

Since 1964, Arab countries, concerned over Israeli plans to divert waters of the Jordan River into the coastal plain, had been trying to divert the headwaters to deprive Israel of water resources, provoking tensions between Israel on the one hand, and Syria and Lebanon on the other. Arab nationalists led by Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser refused to recognize Israel and called for its destruction. By 1966, Israeli-Arab relations had deteriorated to the point of actual battles taking place between Israeli and Arab forces. In May 1967, Egypt massed its army near the border with Israel, expelled UN peacekeepers, stationed in the Sinai Peninsula since 1957, and blocked Israel’s access to the Red Sea. Other Arab states mobilized their forces. Israel reiterated that these actions were a casus belli and, on 5 June, launched a pre-emptive strike against Egypt. Jordan, Syria and Iraq responded and attacked Israel. In a Six-Day War, Israel defeated Jordan and captured the West Bank, defeated Egypt and captured the Gaza Strip and Sinai Peninsula, and defeated Syria and captured the Golan Heights. Jerusalem’s boundaries were enlarged, incorporating East Jerusalem, and the 1949 Green Line became the administrative boundary between Israel and the occupied territories.

Following the 1967 war and the “Three No’s” resolution of the Arab League and during the 1967–1970 War of Attrition, Israel faced attacks from the Egyptians in the Sinai Peninsula, and from Palestinian groups targeting Israelis in the occupied territories, in Israel proper, and around the world. Most important among the various Palestinian and Arab groups was the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), established in 1964, which initially committed itself to “armed struggle as the only way to liberate the homeland”. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Palestinian groups launched a wave of attacks against Israeli and Jewish targets around the world, including a massacre of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich. The Israeli government responded with an assassination campaign against the organizers of the massacre, a bombing and a raid on the PLO headquarters in Lebanon.

On 6 October 1973, as Jews were observing Yom Kippur, the Egyptian and Syrian armies launched a surprise attack against Israeli forces in the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights, that opened the Yom Kippur War. The war ended on 25 October with Israel successfully repelling Egyptian and Syrian forces but having suffered over 2,500 soldiers killed in a war which collectively took 10–35,000 lives in about 20 days. An internal inquiry exonerated the government of responsibility for failures before and during the war, but public anger forced Prime Minister Golda Meir to resign. In July 1976, an airliner was hijacked during its flight from Israel to France by Palestinian guerrillas and landed at Entebbe, Uganda. Israeli commandos carried out an operation in which 102 out of 106 Israeli hostages were successfully rescued.

Further conflict and peace process

The 1977 Knesset elections marked a major turning point in Israeli political history as Menachem Begin’s Likud party took control from the Labor Party. Later that year, Egyptian President Anwar El Sadat made a trip to Israel and spoke before the Knesset in what was the first recognition of Israel by an Arab head of state. In the two years that followed, Sadat and Begin signed the Camp David Accords (1978) and the Israel–Egypt Peace Treaty (1979). In return, Israel withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula and agreed to enter negotiations over an autonomy for Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

On 11 March 1978, a PLO guerilla raid from Lebanon led to the Coastal Road massacre. Israel responded by launching an invasion of southern Lebanon to destroy the PLO bases south of the Litani River. Most PLO fighters withdrew, but Israel was able to secure southern Lebanon until a UN force and the Lebanese army could take over. The PLO soon resumed its policy of attacks against Israel. In the next few years, the PLO infiltrated the south and kept up a sporadic shelling across the border. Israel carried out numerous retaliatory attacks by air and on the ground.

Israel’s 1980 law declared that “Jerusalem, complete and united, is the capital of Israel.”

Meanwhile, Begin’s government provided incentives for Israelis to settle in the occupied West Bank, increasing friction with the Palestinians in that area. The Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel, passed in 1980, was believed by some to reaffirm Israel’s 1967 annexation of Jerusalem by government decree, and reignited international controversy over the status of the city. No Israeli legislation has defined the territory of Israel and no act specifically included East Jerusalem therein. The position of the majority of UN member states is reflected in numerous resolutions declaring that actions taken by Israel to settle its citizens in the West Bank, and impose its laws and administration on East Jerusalem, are illegal and have no validity. In 1981 Israel annexed the Golan Heights, although annexation was not recognized internationally. Israel’s population diversity expanded in the 1980s and 1990s. Several waves of Ethiopian Jews immigrated to Israel since the 1980s, while between 1990 and 1994, immigration from the post-Soviet states increased Israel’s population by twelve percent.

On 7 June 1981, the Israeli air force destroyed Iraq’s sole nuclear reactor under construction just outside Baghdad, in order to impede Iraq’s nuclear weapons program. Following a series of PLO attacks in 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon that year to destroy the bases from which the PLO launched attacks and missiles into northern Israel. In the first six days of fighting, the Israelis destroyed the military forces of the PLO in Lebanon and decisively defeated the Syrians. An Israeli government inquiry—the Kahan Commission—would later hold Begin and several Israeli generals as indirectly responsible for the Sabra and Shatila massacre and hold Defense minister Ariel Sharon as bearing “personal responsibility” for the massacre. Sharon was forced to resign as Defense Minister. In 1985, Israel responded to a Palestinian terrorist attack in Cyprus by bombing the PLO headquarters in Tunisia. Israel withdrew from most of Lebanon in 1986, but maintained a borderland buffer zone in southern Lebanon until 2000, from where Israeli forces engaged in conflict with Hezbollah. The First Intifada, a Palestinian uprising against Israeli rule, broke out in 1987, with waves of uncoordinated demonstrations and violence occurring in the occupied West Bank and Gaza. Over the following six years, the Intifada became more organised and included economic and cultural measures aimed at disrupting the Israeli occupation. More than a thousand people were killed in the violence. During the 1991 Gulf War, the PLO supported Saddam Hussein and Iraqi Scud missile attacks against Israel. Despite public outrage, Israel heeded American calls to refrain from hitting back and did not participate in that war.

Shimon Peres (left) with Yitzhak Rabin (center) and King Hussein of Jordan (right), prior to signing the Israel–Jordan peace treaty in 1994.

In 1992, Yitzhak Rabin became Prime Minister following an election in which his party called for compromise with Israel’s neighbors. The following year, Shimon Peres on behalf of Israel, and Mahmoud Abbas for the PLO, signed the Oslo Accords, which gave the Palestinian National Authority the right to govern parts of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The PLO also recognized Israel’s right to exist and pledged an end to terrorism. In 1994, the Israel–Jordan peace treaty was signed, making Jordan the second Arab country to normalize relations with Israel. Arab public support for the Accords was damaged by the continuation of Israeli settlements and checkpoints, and the deterioration of economic conditions. Israeli public support for the Accords waned as Israel was struck by Palestinian suicide attacks. In November 1995, while leaving a peace rally, Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by Yigal Amir, a far-right-wing Jew who opposed the Accords.

The site of the 2001 Tel Aviv Dolphinarium discotheque massacre, in which 21 Israelis were killed.

Under the leadership of Benjamin Netanyahu at the end of the 1990s, Israel withdrew from Hebron, and signed the Wye River Memorandum, giving greater control to the Palestinian National Authority. Ehud Barak, elected Prime Minister in 1999, began the new millennium by withdrawing forces from Southern Lebanon and conducting negotiations with Palestinian Authority Chairman Yasser Arafat and U.S. President Bill Clinton at the 2000 Camp David Summit. During the summit, Barak offered a plan for the establishment of a Palestinian state. The proposed state included the entirety of the Gaza Strip and over 90% of the West Bank with Jerusalem as a shared capital. Each side blamed the other for the failure of the talks. After a controversial visit by Likud leader Ariel Sharon to the Temple Mount, the Second Intifada began. Some commentators contend that the uprising was pre-planned by Arafat due to the collapse of peace talks. Sharon became prime minister in a 2001 special election. During his tenure, Sharon carried out his plan to unilaterally withdraw from the Gaza Strip and also spearheaded the construction of the Israeli West Bank barrier, ending the Intifada. By this time 1,100 Israelis had been killed, mostly in suicide bombings. The Palestinian fatalities, from 2000 to 2008, reached 4,791 killed by Israeli security forces, 44 killed by Israeli civilians, and 609 killed by Palestinians.

In July 2006, a Hezbollah artillery assault on Israel’s northern border communities and a cross-border abduction of two Israeli soldiers precipitated the month-long Second Lebanon War. On 6 September 2007, the Israeli Air Force destroyed a nuclear reactor in Syria. At the end of 2008, Israel entered another conflict as a ceasefire between Hamas and Israel collapsed. The 2008–09 Gaza War lasted three weeks and ended after Israel announced a unilateral ceasefire. Hamas announced its own ceasefire, with its own conditions of complete withdrawal and opening of border crossings. Despite neither the rocket launchings nor Israeli retaliatory strikes having completely stopped, the fragile ceasefire remained in order. In what Israel described as a response to more than a hundred Palestinian rocket attacks on southern Israeli cities, Israel began an operation in Gaza on 14 November 2012, lasting eight days. Israel started another operation in Gaza following an escalation of rocket attacks by Hamas in July 2014.

In September 2010, Israel was invited to join the OECD. Israel has also signed free trade agreements with the European Union, the United States, the European Free Trade Association, Turkey, Mexico, Canada, Jordan, and Egypt, and in 2007, it became the first non-Latin-American country to sign a free trade agreement with the Mercosur trade bloc. By the 2010s, the increasing regional cooperation between Israel and Arab League countries, with many of whom peace agreements (Jordan, Egypt) diplomatic relations (UAE, Palestine) and unofficial relations (Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Tunisia), have been established, the Israeli security situation shifted from the traditional Arab–Israeli hostility towards regional rivalry with Iran and its proxies. The Iranian–Israeli conflict gradually emerged from the declared hostility of post-revolutionary Islamic Republic of Iran towards Israel since 1979, into covert Iranian support of Hezbollah during the South Lebanon conflict (1985–2000) and essentially developed into a proxy regional conflict from 2005. With increasing Iranian involvement in the Syrian Civil War from 2011 the conflict shifted from proxy warfare into direct confrontation by early 2018.

Geography and environment

plain

Mountains

Valley

(Mediterranean)

Sea

of Eilat

Bank

Strip

Israel is located in the Levant area of the Fertile Crescent region. The country is at the eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea, bounded by Lebanon to the north, Syria to the northeast, Jordan and the West Bank to the east, and Egypt and the Gaza Strip to the southwest. It lies between latitudes 29° and 34° N, and longitudes 34° and 36° E.

The sovereign territory of Israel (according to the demarcation lines of the 1949 Armistice Agreements and excluding all territories captured by Israel during the 1967 Six-Day War) is approximately 20,770 square kilometers (8,019 sq mi) in area, of which two percent is water. However Israel is so narrow (100 km at its widest, compared to 400 km from north to south) that the exclusive economic zone in the Mediterranean is double the land area of the country. The total area under Israeli law, including East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights, is 22,072 square kilometers (8,522 sq mi), and the total area under Israeli control, including the military-controlled and partially Palestinian-governed territory of the West Bank, is 27,799 square kilometers (10,733 sq mi).

Despite its small size, Israel is home to a variety of geographic features, from the Negev desert in the south to the inland fertile Jezreel Valley, mountain ranges of the Galilee, Carmel and toward the Golan in the north. The Israeli coastal plain on the shores of the Mediterranean is home to most of the nation’s population. East of the central highlands lies the Jordan Rift Valley, which forms a small part of the 6,500-kilometer (4,039 mi) Great Rift Valley. The Jordan River runs along the Jordan Rift Valley, from Mount Hermon through the Hulah Valley and the Sea of Galilee to the Dead Sea, the lowest point on the surface of the Earth. Further south is the Arabah, ending with the Gulf of Eilat, part of the Red Sea. Unique to Israel and the Sinai Peninsula are makhteshim, or erosion cirques. The largest makhtesh in the world is Ramon Crater in the Negev, which measures 40 by 8 kilometers (25 by 5 mi). A report on the environmental status of the Mediterranean Basin states that Israel has the largest number of plant species per square meter of all the countries in the basin. Israel contains four terrestrial ecoregions: Eastern Mediterranean conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf forests, Southern Anatolian montane conifer and deciduous forests, Arabian Desert, and Mesopotamian shrub desert. It had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.14/10, ranking it 135th globally out of 172 countries.

Tectonics and seismicity

The Jordan Rift Valley is the result of tectonic movements within the Dead Sea Transform (DSF) fault system. The DSF forms the transform boundary between the African Plate to the west and the Arabian Plate to the east. The Golan Heights and all of Jordan are part of the Arabian Plate, while the Galilee, West Bank, Coastal Plain, and Negev along with the Sinai Peninsula are on the African Plate. This tectonic disposition leads to a relatively high seismic activity in the region. The entire Jordan Valley segment is thought to have ruptured repeatedly, for instance during the last two major earthquakes along this structure in 749 and 1033. The deficit in slip that has built up since the 1033 event is sufficient to cause an earthquake of Mw ~7.4.

The most catastrophic known earthquakes occurred in 31 BCE, 363, 749, and 1033 CE, that is every ca. 400 years on average. Destructive earthquakes leading to serious loss of life strike about every 80 years. While stringent construction regulations are currently in place and recently built structures are earthquake-safe, as of 2007 the majority of the buildings in Israel were older than these regulations and many public buildings as well as 50,000 residential buildings did not meet the new standards and were “expected to collapse” if exposed to a strong earthquake.

Climate

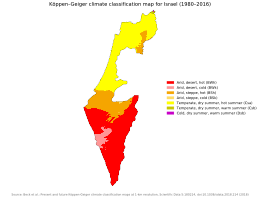

Köppen climate classification map of Israel and the Golan Heights

Temperatures in Israel vary widely, especially during the winter. Coastal areas, such as those of Tel Aviv and Haifa, have a typical Mediterranean climate with cool, rainy winters and long, hot summers. The area of Beersheba and the Northern Negev have a semi-arid climate with hot summers, cool winters, and fewer rainy days than the Mediterranean climate. The Southern Negev and the Arava areas have a desert climate with very hot, dry summers, and mild winters with few days of rain. The highest temperature in the continent of Asia (54.0 °C or 129.2 °F) was recorded in 1942 at Tirat Zvi kibbutz in the northern Jordan River valley.

At the other extreme, mountainous regions can be windy and cold, and areas at elevation of 750 metres (2,460 ft) or more (same elevation as Jerusalem) will usually receive at least one snowfall each year. From May to September, rain in Israel is rare. With scarce water resources, Israel has developed various water-saving technologies, including drip irrigation. Israelis also take advantage of the considerable sunlight available for solar energy, making Israel the leading nation in solar energy use per capita (practically every house uses solar panels for water heating).

Four different phytogeographic regions exist in Israel, due to the country’s location between the temperate and tropical zones, bordering the Mediterranean Sea in the west and the desert in the east. For this reason, the flora and fauna of Israel are extremely diverse. There are 2,867 known species of plants found in Israel. Of these, at least 253 species are introduced and non-native. There are 380 Israeli nature reserves.

Demographics

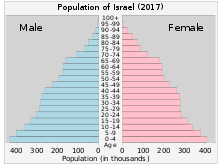

Population pyramid of Israel

As of 2021, Israel’s population was an estimated 9,312,700, of whom 74.2% were recorded by the civil government as Jews. Arabs accounted for 20.9% of the population, while non-Arab Christians and people who have no religion listed in the civil registry made up 4.8%. Over the last decade, large numbers of migrant workers from Romania, Thailand, China, Africa, and South America have settled in Israel. Exact figures are unknown, as many of them are living in the country illegally, but estimates run from 166,000 to 203,000. By June 2012, approximately 60,000 African migrants had entered Israel. About 92% of Israelis live in urban areas. Data published by the OECD in 2016 estimated the average life expectancy of Israelis at 82.5 years, making it the 6th-highest in the world.

Immigration to Israel in the years 1948–2015. The two peaks were in 1949 and 1990.

Israel was established as a homeland for the Jewish people and is often referred to as a Jewish state. The country’s Law of Return grants all Jews and those of Jewish ancestry the right to Israeli citizenship. Retention of Israel’s population since 1948 is about even or greater, when compared to other countries with mass immigration. Jewish emigration from Israel (called yerida in Hebrew), primarily to the United States and Canada, is described by demographers as modest, but is often cited by Israeli government ministries as a major threat to Israel’s future.

Three quarters of the population are Jews from a diversity of Jewish backgrounds. Approximately 75% of Israeli Jews are born in Israel, 16% are immigrants from Europe and the Americas, and 7% are immigrants from Asia and Africa (including the Arab world). Jews from Europe and the former Soviet Union and their descendants born in Israel, including Ashkenazi Jews, constitute approximately 50% of Jewish Israelis. Jews who left or fled Arab and Muslim countries and their descendants, including both Mizrahi and Sephardi Jews, form most of the rest of the Jewish population. Jewish intermarriage rates run at over 35% and recent studies suggest that the percentage of Israelis descended from both Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews increases by 0.5 percent every year, with over 25% of school children now originating from both communities. Around 4% of Israelis (300,000), ethnically defined as “others”, are Russian descendants of Jewish origin or family who are not Jewish according to rabbinical law, but were eligible for Israeli citizenship under the Law of Return.

The total number of Israeli settlers beyond the Green Line is over 600,000 (≈10% of the Jewish Israeli population). In 2016, 399,300 Israelis lived in West Bank settlements, including those that predated the establishment of the State of Israel and which were re-established after the Six-Day War, in cities such as Hebron and Gush Etzion bloc. In addition to the West Bank settlements, there were more than 200,000 Jews living in East Jerusalem, and 22,000 in the Golan Heights. Approximately 7,800 Israelis lived in settlements in the Gaza Strip, known as Gush Katif, until they were evacuated by the government as part of its 2005 disengagement plan.

Major urban areas

View over Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area

There are four major metropolitan areas: Gush Dan (Tel Aviv metropolitan area; population 3,854,000), Jerusalem metropolitan area (population 1,253,900), Haifa metropolitan area (population 924,400), and Beersheba metropolitan area (population 377,100).

Israel’s largest municipality, in population and area, is Jerusalem with 936,425 residents in an area of 125 square kilometres (48 sq mi). Israeli government statistics on Jerusalem include the population and area of East Jerusalem, which is widely recognized as part of the Palestinian territories under Israeli occupation. Tel Aviv and Haifa rank as Israel’s next most populous cities, with populations of 460,613 and 285,316, respectively.

Israel has 16 cities with populations over 100,000. In all, there are 77 Israeli localities granted “municipalities” (or “city”) status by the Ministry of the Interior, four of which are in the West Bank. Two more cities are planned: Kasif, a planned city to be built in the Negev, and Harish, originally a small town that is being built into a large city since 2015.

|

Largest cities in Israel Israel Central Bureau of Statistics

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | Rank | Name | District | Pop. | ||

Jerusalem  Tel Aviv |

1 | Jerusalem | Jerusalem | 936,425a | 11 | Ramat Gan | Tel Aviv | 163,480 |  Haifa  Rishon LeZion |

| 2 | Tel Aviv | Tel Aviv | 460,613 | 12 | Rehovot | Central | 143,904 | ||

| 3 | Haifa | Haifa | 285,316 | 13 | Ashkelon | Southern | 144,073 | ||

| 4 | Rishon LeZion | Central | 254,384 | 14 | Bat Yam | Tel Aviv | 129,013 | ||

| 5 | Petah Tikva | Central | 247,956 | 15 | Beit Shemesh | Jerusalem | 124,957 | ||

| 6 | Ashdod | Southern | 225,939 | 16 | Kfar Saba | Central | 101,432 | ||

| 7 | Netanya | Central | 221,353 | 17 | Herzliya | Tel Aviv | 97,470 | ||

| 8 | Beersheba | Southern | 209,687 | 18 | Hadera | Haifa | 97,335 | ||

| 9 | Bnei Brak | Tel Aviv | 204,639 | 19 | Modi’in-Maccabim-Re’ut | Central | 93,277 | ||

| 10 | Holon | Tel Aviv | 196,282 | 20 | Nazareth | Northern | 77,445 | ||

^a This number includes East Jerusalem and West Bank areas, which had a total population of 542,410 inhabitants in 2016. Israeli sovereignty over East Jerusalem is internationally unrecognized.

Language

Road sign in Hebrew, Arabic, and English

Israel has one official language, Hebrew. Arabic had been an official language of the State of Israel; in 2018 it was downgraded to having a ‘special status in the state’ with its use by state institutions to be set in law. Hebrew is the primary language of the state and is spoken every day by the majority of the population. Arabic is spoken by the Arab minority, with Hebrew taught in Arab schools.

As a country of immigrants, many languages can be heard on the streets. Due to mass immigration from the former Soviet Union and Ethiopia (some 130,000 Ethiopian Jews live in Israel), Russian and Amharic are widely spoken. More than one million Russian-speaking immigrants arrived in Israel from the post-Soviet states between 1990 and 2004. French is spoken by around 700,000 Israelis, mostly originating from France and North Africa (see Maghrebi Jews). English was an official language during the Mandate period; it lost this status after the establishment of Israel, but retains a role comparable to that of an official language, as may be seen in road signs and official documents. Many Israelis communicate reasonably well in English, as many television programs are broadcast in English with subtitles and the language is taught from the early grades in elementary school. In addition, Israeli universities offer courses in the English language on various subjects.

Religion

Religion in Israel

Until 1995, figures for Christians also included Others.

Israel comprises a major part of the Holy Land, a region of significant importance to all Abrahamic religions – Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Druze and Baháʼí Faith.

The religious affiliation of Israeli Jews varies widely: a social survey from 2016 made by Pew Research indicates that 49% self-identify as Hiloni (secular), 29% as Masorti (traditional), 13% as Dati (religious) and 9% as Haredi (ultra-Orthodox). Haredi Jews are expected to represent more than 20% of Israel’s Jewish population by 2028.

Muslims constitute Israel’s largest religious minority, making up about 17.6% of the population. About 2% of the population is Christian and 1.6% is Druze. The Christian population is composed primarily of Arab Christians and Aramean Christians, but also includes post-Soviet immigrants, the foreign laborers of multinational origins, and followers of Messianic Judaism, considered by most Christians and Jews to be a form of Christianity. Members of many other religious groups, including Buddhists and Hindus, maintain a presence in Israel, albeit in small numbers. Out of more than one million immigrants from the former Soviet Union, about 300,000 are considered not Jewish by the Chief Rabbinate of Israel.

The Dome of the Rock and the Western Wall, Jerusalem.

The city of Jerusalem is of special importance to Jews, Muslims, and Christians, as it is the home of sites that are pivotal to their religious beliefs, such as the Old City that incorporates the Western Wall and the Temple Mount, the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Other locations of religious importance in Israel are Nazareth (holy in Christianity as the site of the Annunciation of Mary), Tiberias and Safed (two of the Four Holy Cities in Judaism), the White Mosque in Ramla (holy in Islam as the shrine of the prophet Saleh), and the Church of Saint George in Lod (holy in Christianity and Islam as the tomb of Saint George or Al Khidr). A number of other religious landmarks are located in the West Bank, among them Joseph’s Tomb in Nablus, the birthplace of Jesus and Rachel’s Tomb in Bethlehem, and the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron. The administrative center of the Baháʼí Faith and the Shrine of the Báb are located at the Baháʼí World Centre in Haifa; the leader of the faith is buried in Acre. A few kilometres south of the Baháʼí World Centre is Mahmood Mosque affiliated with the reformist Ahmadiyya movement. Kababir, Haifa’s mixed neighbourhood of Jews and Ahmadi Arabs is one of a few of its kind in the country, others being Jaffa, Acre, other Haifa neighborhoods, Harish and Upper Nazareth.

Education

Multidisciplinary Brain Research Center at Bar-Ilan University

Education is highly valued in the Israeli culture and was viewed as a fundamental block of ancient Israelites. Jewish communities in the Levant were the first to introduce compulsory education for which the organized community, not less than the parents was responsible. Many international business leaders such as Microsoft founder Bill Gates have praised Israel for its high quality of education in helping spur Israel’s economic development and technological boom. In 2015, the country ranked third among OECD members (after Canada and Japan) for the percentage of 25–64 year-olds that have attained tertiary education with 49% compared with the OECD average of 35%. In 2012, the country ranked third in the world in the number of academic degrees per capita (20 percent of the population).

Israel has a school life expectancy of 16 years and a literacy rate of 97.8%. The State Education Law, passed in 1953, established five types of schools: state secular, state religious, ultra orthodox, communal settlement schools, and Arab schools. The public secular is the largest school group, and is attended by the majority of Jewish and non-Arab pupils in Israel. Most Arabs send their children to schools where Arabic is the language of instruction. Education is compulsory in Israel for children between the ages of three and eighteen. Schooling is divided into three tiers – primary school (grades 1–6), middle school (grades 7–9), and high school (grades 10–12) – culminating with Bagrut matriculation exams. Proficiency in core subjects such as mathematics, the Hebrew language, Hebrew and general literature, the English language, history, Biblical scripture and civics is necessary to receive a Bagrut certificate. Israel’s Jewish population maintains a relatively high level of educational attainment where just under half of all Israeli Jews (46%) hold post-secondary degrees. This figure has remained stable in their already high levels of educational attainment over recent generations. Israeli Jews (among those ages 25 and older) have average of 11.6 years of schooling making them one of the most highly educated of all major religious groups in the world. In Arab, Christian and Druze schools, the exam on Biblical studies is replaced by an exam on Muslim, Christian or Druze heritage. Maariv described the Christian Arabs sectors as “the most successful in education system”, since Christians fared the best in terms of education in comparison to any other religion in Israel. Israeli children from Russian-speaking families have a higher bagrut pass rate at high-school level. Amongst immigrant children born in the Former Soviet Union, the bagrut pass rate is higher amongst those families from European FSU states at 62.6% and lower amongst those from Central Asian and Caucasian FSU states. In 2014, 61.5% of all Israeli twelfth graders earned a matriculation certificate.

Mount Scopus Campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Israel has a tradition of higher education where its quality university education has been largely responsible in spurring the nations modern economic development. Israel has nine public universities that are subsidized by the state and 49 private colleges. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel’s second-oldest university after the Technion, houses the National Library of Israel, the world’s largest repository of Judaica and Hebraica. The Technion and the Hebrew University consistently ranked among world’s 100 top universities by the prestigious ARWU academic ranking. Other major universities in the country include the Weizmann Institute of Science, Tel Aviv University, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Bar-Ilan University, the University of Haifa and the Open University of Israel. Ariel University, in the West Bank, is the newest university institution, upgraded from college status, and the first in over thirty years.

Government and politics

Reuven Rivlin

Benjamin Netanyahu

The Knesset chamber, home to the Israeli parliament

Israel is a parliamentary democracy with universal suffrage. A member of parliament supported by a parliamentary majority becomes the prime minister—usually this is the chair of the largest party. The prime minister is the head of government and head of the cabinet.

Israel is governed by a 120-member parliament, known as the Knesset. Membership of the Knesset is based on proportional representation of political parties, with a 3.25% electoral threshold, which in practice has resulted in coalition governments. Residents of Israeli settlements in the West Bank are eligible to vote and after the 2015 election, 10 of the 120 MKs (8%) were settlers. Parliamentary elections are scheduled every four years, but unstable coalitions or a no-confidence vote by the Knesset can dissolve a government earlier.

Political system of state of Israel

The Basic Laws of Israel function as an uncodified constitution. In 2003, the Knesset began to draft an official constitution based on these laws.

The president of Israel is head of state, with limited and largely ceremonial duties.

Israel has no official religion, but the definition of the state as “Jewish and democratic” creates a strong connection with Judaism, as well as a conflict between state law and religious law. Interaction between the political parties keeps the balance between state and religion largely as it existed during the British Mandate.

On 19 July 2018, the Israeli Parliament passed a Basic Law that characterizes the State of Israel as principally a “Nation State of the Jewish People,” and Hebrew as its official language. The bill ascribes “special status” to the Arabic language. The same bill gives Jews a unique right to national self-determination, and views the developing of Jewish settlement in the country as “a national interest,” empowering the government to “take steps to encourage, advance and implement this interest.”

Legal system

Supreme Court of Israel, Givat Ram, Jerusalem

Israel has a three-tier court system. At the lowest level are magistrate courts, situated in most cities across the country. Above them are district courts, serving as both appellate courts and courts of first instance; they are situated in five of Israel’s six districts. The third and highest tier is the Supreme Court, located in Jerusalem; it serves a dual role as the highest court of appeals and the High Court of Justice. In the latter role, the Supreme Court rules as a court of first instance, allowing individuals, both citizens and non-citizens, to petition against the decisions of state authorities. Although Israel supports the goals of the International Criminal Court, it has not ratified the Rome Statute, citing concerns about the ability of the court to remain free from political impartiality.

Israel’s legal system combines three legal traditions: English common law, civil law, and Jewish law. It is based on the principle of stare decisis (precedent) and is an adversarial system, where the parties in the suit bring evidence before the court. Court cases are decided by professional judges rather than juries. Marriage and divorce are under the jurisdiction of the religious courts: Jewish, Muslim, Druze, and Christian. The election of judges is carried out by a committee of two Knesset members, three Supreme Court justices, two Israeli Bar members and two ministers (one of which, Israel’s justice minister, is the committee’s chairman). The committee’s members of the Knesset are secretly elected by the Knesset, and one of them is traditionally a member of the opposition, the committee’s Supreme Court justices are chosen by tradition from all Supreme Court justices by seniority, the Israeli Bar members are elected by the bar, and the second minister is appointed by the Israeli cabinet. The current justice minister and committee’s chairwoman is Ayelet Shaked. Administration of Israel’s courts (both the “General” courts and the Labor Courts) is carried by the Administration of Courts, situated in Jerusalem. Both General and Labor courts are paperless courts: the storage of court files, as well as court decisions, are conducted electronically. Israel’s Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty seeks to defend human rights and liberties in Israel. As a result of “Enclave law”, large portions of Israeli civil law are applied to Israeli settlements and Israeli residents in the occupied territories.

Administrative divisions

and

Samaria

Area

The State of Israel is divided into six main administrative districts, known as mehozot (Hebrew: מחוזות; singular: mahoz) – Center, Haifa, Jerusalem, North, South, and Tel Aviv districts, as well as the Judea and Samaria Area in the West Bank. All of the Judea and Samaria Area and parts of the Jerusalem and Northern districts are not recognized internationally as part of Israel. Districts are further divided into fifteen sub-districts known as nafot (Hebrew: נפות; singular: nafa), which are themselves partitioned into fifty natural regions.

| District | Capital | Largest city | Population | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jews | Arabs | Total | note | |||

| Jerusalem | Jerusalem | 67% | 32% | 1,083,300 | a | |

| North | Nof HaGalil | Nazareth | 43% | 54% | 1,401,300 | |

| Haifa | Haifa | 68% | 26% | 996,300 | ||

| Center | Ramla | Rishon LeZion | 88% | 8% | 2,115,800 | |

| Tel Aviv | Tel Aviv | 93% | 2% | 1,388,400 | ||

| South | Beersheba | Ashdod | 73% | 20% | 1,244,200 | |

| Judea and Samaria Area | Ariel | Modi’in Illit | 98% | 0% | 399,300 | b |

- ^a Including over 200,000 Jews and 300,000 Arabs in East Jerusalem.

- ^b Israeli citizens only.

Specific types of settlements

- Communal settlement

- Jewish locality

- Kibbutz

- Kvutza

- Moshav

- Moshava

Israeli-occupied territories

Map of Israel showing the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and the Golan Heights

| Area | Administered by | Recognition of governing authority | Sovereignty claimed by | Recognition of claim | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaza Strip | Palestinian National Authority (PA) (currently Hamas-led); under Israeli occupation | Witnesses to the Oslo II Accord | State of Palestine | 137 UN member states | |

| West Bank | Area A | PA (currently Fatah-led); under Israeli occupation | |||

| Area B | PA (currently Fatah-led) and Israeli military; under Israeli occupation | ||||

| Area C | Israeli military (Palestinians) under Israeli occupation, and Israeli enclave law (Israeli settlements) | ||||

| East Jerusalem | Israeli government | Honduras, Guatemala, Nauru, and the United States | China, Russia | ||

| West Jerusalem | Australia, Russia, Czechia, Honduras, Guatemala, Nauru, and the United States | United Nations as an international city along with East Jerusalem | Various UN member states and the European Union; joint sovereignty also widely supported | ||

| Golan Heights | United States | Syria | All UN member states except the United States | ||

| Israel (proper) | 163 UN member states | Israel | 163 UN member states | ||

In 1967, as a result of the Six-Day War, Israel captured and occupied the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, the Gaza Strip and the Golan Heights. Israel also captured the Sinai Peninsula, but returned it to Egypt as part of the 1979 Egypt–Israel peace treaty. Between 1982 and 2000, Israel occupied part of southern Lebanon, in what was known as the Security Belt. Since Israel’s capture of these territories, Israeli settlements and military installations have been built within each of them, except Lebanon.

The Golan Heights and East Jerusalem have been fully incorporated into Israel under Israeli law, but not under international law. Israel has applied civilian law to both areas and granted their inhabitants permanent residency status and the ability to apply for citizenship. The UN Security Council has declared the annexation of the Golan Heights and East Jerusalem to be “null and void” and continues to view the territories as occupied. The status of East Jerusalem in any future peace settlement has at times been a difficult issue in negotiations between Israeli governments and representatives of the Palestinians, as Israel views it as its sovereign territory, as well as part of its capital.

Israeli West Bank barrier separating Israel and the West Bank

The West Bank excluding East Jerusalem is known in Israeli law as the Judea and Samaria Area; the almost 400,000 Israeli settlers residing in the area are considered part of Israel’s population, have Knesset representation, a large part of Israel’s civil and criminal laws applied to them, and their output is considered part of Israel’s economy. The land itself is not considered part of Israel under Israeli law, as Israel has consciously refrained from annexing the territory, without ever relinquishing its legal claim to the land or defining a border with the area. There is no border between Israel-proper and the West Bank for Israeli vehicles. Israeli political opposition to annexation is primarily due to the perceived “demographic threat” of incorporating the West Bank’s Palestinian population into Israel. Outside of the Israeli settlements, the West Bank remains under direct Israeli military rule, and Palestinians in the area cannot become Israeli citizens. The international community maintains that Israel does not have sovereignty in the West Bank, and considers Israel’s control of the area to be the longest military occupation is modern history. The West Bank was occupied and annexed by Jordan in 1950, following the Arab rejection of the UN decision to create two states in Palestine. Only Britain recognized this annexation and Jordan has since ceded its claim to the territory to the PLO. The population are mainly Palestinians, including refugees of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. From their occupation in 1967 until 1993, the Palestinians living in these territories were under Israeli military administration. Since the Israel–PLO letters of recognition, most of the Palestinian population and cities have been under the internal jurisdiction of the Palestinian Authority, and only partial Israeli military control, although Israel has on several occasions redeployed its troops and reinstated full military administration during periods of unrest. In response to increasing attacks during the Second Intifada, the Israeli government started to construct the Israeli West Bank barrier. When completed, approximately 13% of the barrier will be constructed on the Green Line or in Israel with 87% inside the West Bank.

Area C of the West Bank, controlled by Israel under Oslo Accords, in blue and red, in December 2011

The Gaza Strip is considered to be a “foreign territory” under Israeli law; however, since Israel operates a land, air, and sea blockade of the Gaza Strip, together with Egypt, the international community considers Israel to be the occupying power. The Gaza Strip was occupied by Egypt from 1948 to 1967 and then by Israel after 1967. In 2005, as part of Israel’s unilateral disengagement plan, Israel removed all of its settlers and forces from the territory, however, it continues to maintain control of its airspace and waters. The international community, including numerous international humanitarian organizations and various bodies of the UN, consider Gaza to remain occupied. Following the 2007 Battle of Gaza, when Hamas assumed power in the Gaza Strip, Israel tightened its control of the Gaza crossings along its border, as well as by sea and air, and prevented persons from entering and exiting the area except for isolated cases it deemed humanitarian. Gaza has a border with Egypt, and an agreement between Israel, the European Union, and the PA governed how border crossing would take place (it was monitored by European observers). The application of democracy to its Palestinian citizens, and the selective application of Israeli democracy in the Israeli-controlled Palestinian territories, has been criticized.