A marketplace or market place is a location where people regularly gather for the purchase and sale of provisions, livestock, and other goods. In different parts of the world, a marketplace may be described as a souk (from the Arabic), bazaar (from the Persian), a fixed mercado (Spanish), or itinerant tianguis (Mexico), or palengke (Philippines). Some markets operate daily and are said to be permanent markets while others are held once a week or on less frequent specified days such as festival days and are said to be periodic markets. The form that a market adopts depends on its locality’s population, culture, ambient and geographic conditions. The term market covers many types of trading, as market squares, market halls and food halls, and their different varieties. Thus marketplaces can be both outdoors and indoors, and in the modern world, online marketplaces.

Markets have existed for as long as humans have engaged in trade. The earliest bazaars are believed to have originated in Persia, from where they spread to the rest of the Middle East and Europe. Documentary sources suggest that zoning policies confined trading to particular parts of cities from around 3000 BCE, creating the conditions necessary for the emergence of a bazaar. Middle Eastern bazaars were typically long strips with stalls on either side and a covered roof designed to protect traders and purchasers from the fierce sun. In Europe, informal, unregulated markets gradually made way for a system of formal, chartered markets from the 12th century. Throughout the medieval period, increased regulation of marketplace practices, especially weights and measures, gave consumers confidence in the quality of market goods and the fairness of prices. Around the globe, markets have evolved in different ways depending on local ambient conditions, especially weather, tradition, and culture. In the Middle East, markets tend to be covered, to protect traders and shoppers from the sun. In milder climates, markets are often open air. In Asia, a system of morning markets trading in fresh produce and night markets trading in non-perishables is common.

Today, markets can also be accessed electronically or on the internet through e-commerce or matching platforms. In many countries, shopping at a local market is a standard feature of daily life. Given the market’s role in ensuring food supply for a population, markets are often highly regulated by a central authority. In many places, designated market places have become listed sites of historic and architectural significance and represent part of a town’s or nation’s cultural assets. For these reasons, they are often popular tourist destinations.

Etymology

The term market comes from the Latin mercatus (“market place”). The earliest recorded use of the term market in English is in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of 963, a work that was created during the reign of Alfred the Great (r. 871–899) and subsequently distributed, copied throughout English monasteries. The exact phrase was “Ic wille þæt markete beo in þe selue tun“, which roughly translates as “I want to be at that market in the good town.”

History

In prehistory

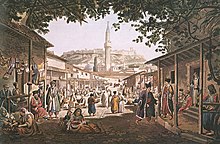

The Bazaar of Athens by Edward Dodwell, 1821

Markets have existed since ancient times. Some historians have argued that a type of market has existed since humans first began to engage in trade. Open air, public markets were known in ancient Babylonia, Assyria, Phoenicia, the Land of Israel, Greece, Egypt and on the Arabian peninsula. However, not all societies developed a system of markets. The Greek historian Herodotus noted that markets did not evolve in ancient Persia.

Across the Mediterranean and Aegean, a network of markets emerged from the early Bronze Age. A vast array of goods were traded, including: salt, lapis lazuli, dyes, cloth, metals, pots, ceramics, statues, spears and other implements. Archaeological evidence suggests that Bronze Age traders segmented trade routes according to geographical circuits. Both produce and ideas travelled along these trade routes.

In the Middle East, documentary sources suggest that a form of bazaar first developed around 3000 BCE. Early bazaars occupied a series of alleys along the length of the city, typically stretching from one city gate to a different gate on the other side of the city. The bazaar at Tabriz, for example, stretches along 1.5 kilometres of street and is the longest vaulted bazaar in the world. Moosavi argues that the Middle Eastern bazaar evolved in a linear pattern, whereas the market places of the West were more centralised. The Greek historian Herodotus noted that in Egypt, roles were reversed compared with other cultures, and Egyptian women frequented the market and carried on trade, while the men remained at home weaving cloth. He also described The Babylonian Marriage Market.

In antiquity

Ruins of the macellum (market-place) at Leptis Magna, Carthage

In antiquity, markets were typically situated in the town’s centre. The market was surrounded by alleyways inhabited by skilled artisans, such as metal-workers, leather workers and carpenters. These artisans may have sold wares directly from their premises, but also prepared goods for sale on market days. Across ancient Greece market places (agorai) were to be found in most city states, where they operated within the agora (open space). Between 550 and 350 BCE, Greek stallholders clustered together according to the type of goods carried – fish-sellers were in one place, clothing in another and sellers of more expensive goods such as perfumes, bottles and jars were located in a separate building. The Greeks organised trade into separate zones, all located near the city centre and known as stoa. A freestanding colonnade with a covered walkway, the stoa was both a place of commerce and a public promenade, situated within or adjacent to the agora. At the market-place (agorai) in Athens, officials were employed by the government to oversee weights, measures, and coinage to ensure that the people were not cheated in market place transactions. The rocky and mountainous terrain in Greece made it difficult for producers to transport goods or surpluses to local markets, giving rise to the kapēlos, a specialised type of retailer who operated as an intermediary purchasing produce from farmers and transporting it over short distances to the city markets.

In ancient Rome, trade took place in the forum. Rome had two forums; the Forum Romanum and Trajan’s Forum. Trajan’s Market at Trajan’s forum, built around 100-110CE, was a vast expanse, comprising multiple buildings with shops on four levels. The Roman forum was arguably the earliest example of a permanent retail shopfront. In antiquity, exchange involved direct selling via merchants or peddlers and bartering systems were commonplace. In the Roman world, the central market primarily served the local peasantry. Market stall holders were primarily local primary producers who sold small surpluses from their individual farming activities and also artisans who sold leather-goods, metal-ware and pottery. Consumers were made up of several different groups; farmers who purchased minor farm equipment and a few luxuries for their homes and urban dwellers who purchased basic necessities. Major producers such as the great estates were sufficiently attractive for merchants to call directly at their farm-gates, obviating the producers’ need to attend local markets. The very wealthy landowners managed their own distribution, which may have involved importing and exporting. The nature of export markets in antiquity is well documented in ancient sources and archaeological case studies.

Trajan’s Market, Rome, Italy

At Pompeii multiple markets served the population of approximately 12,000. Produce markets were located in the vicinity of the Forum, while livestock markets were situated on the city’s perimeter, near the amphitheatre. A long narrow building at the north-west corner of the Forum was some type of market, possibly a cereal market. On the opposite corner stood the macellum, thought to have been a meat and fish market. Market stall-holders paid a market tax for the right to trade on market days. Some archaeological evidence suggests that markets and street vendors were controlled by local government. A graffito on the outside of a large shop documents a seven-day cycle of markets; “Saturn’s day at Pompeii and Nuceria, Sun’s day at Atella and Nola, Moon’s day at Cumae … etc.” The presence of an official commercial calendar suggests something of the market’s importance to community life and trade. Markets were also important centres of social life.

In medieval Europe

Medieval market scene by Joachim Beuckelaer, c. 1560

In early Western Europe, markets developed close to monasteries, castles or royal residences. Priories and aristocratic manorial households created considerable demand for goods and services – both luxuries and necessities and also afforded some protection to merchants and traders. These centres of trade attracted sellers which would stimulate the growth of the town. The Domesday Book of 1086 lists 50 markets in England, however, many historians believe this figure underestimates the actual number of markets in operation at the time. In England, some 2,000 new markets were established between 1200 and 1349. By 1516, England had some 2,464 markets and 2,767 fairs while Wales had 138 markets and 166 fairs.

From the 12th century, English monarchs awarded a charter to local Lords to create markets and fairs for a town or village. A charter protected the town’s trading privileges in return for an annual fee. Once a chartered market was granted for specific market days, a nearby rival market could not open on the same days. Fairs, which were usually held annually, and almost always associated with a religious festival, traded in high value goods, while regular weekly or bi-weekly markets primarily traded in fresh produce and necessities. Although a fair’s primary purpose was trade, it typically included some elements of entertainment, such as dance, music or tournaments. As the number of markets increased, market towns situated themselves sufficiently far apart so as to avoid competition, but close enough to permit local producers a round trip within one day (about 10 km). Some British open-air markets have been operating continuously since the 12th century.

Loggia del Pesce, Florence, (formerly part of the piazza del Mercato Vecchio) just prior to its demolition in 1880

A pattern of market trading using mobile stalls under covered arcades was probably established in Italy with the open loggias of Mercato Nuovo (1547) designed and constructed by Giovanni Battista del Tasso (and funded by the Medici family); Mercato Vecchio, Florence designed by Giorgio Vasari (1567) and Loggia del Grano (1619) by architect, Giulio Parigi.

Braudel and Reynold have made a systematic study of European market towns between the thirteenth and fifteenth century. Their investigation shows that in regional districts markets were held once or twice a week while daily markets were common in larger cities. Over time, permanent shops began opening daily and gradually supplanted the periodic markets, while peddlers or itinerant sellers continued to fill in any gaps in distribution.

During the Middle Ages, the physical market was characterised by transactional exchange. Shops had higher overhead costs, but were able to offer regular trading hours and a relationship with customers and may have offered added value services, such as credit terms to reliable customers. The economy was primarily characterised by local trading in which goods were traded across relatively short distances.

Beach markets, which were known in north-western Europe, during the Viking period, were primarily associated with the sale of fish. From around the 11th-century, the number and variety of imported goods sold at beach markets began to increase. giving consumers access to a broader range of exotic and luxury goods. Throughout the Medieval period, markets became more international. The historian, Braudel, reports that, in 1600, grain moved just 5–10 miles; cattle 40–70 miles; wool and wollen cloth 20–40 miles. However, following the European age of discovery, goods were imported from afar – calico cloth from India, porcelain, silk and tea from China, spices from India and South-East Asia and tobacco, sugar, rum and coffee from the New World.

Performance at the fair by Pieter Brueghel, the younger, late 16th century

Across the boroughs of England, a network of chartered markets sprang up between the 12th and 16th centuries, giving consumers reasonable choice in the markets they preferred to patronise. A study on the purchasing habits of the monks and other individuals in medieval England, suggests that consumers of the period were relatively discerning. Purchase decisions were based on purchase criteria such as the consumer’s perceptions of the range, quality, and price of goods. Such considerations informed decisions about where to make purchases and which markets to patronise.

As the number of charters granted increased, competition between market towns also increased. In response to competitive pressures, towns invested in developing a reputation for quality produce, efficient market regulation and good amenities for visitors such as covered accommodation. By the thirteenth century, counties with important textile industries were investing in purpose built halls for the sale of cloth. London’s Blackwell Hall became a centre for cloth, Bristol became associated with a particular type of cloth known as Bristol red, Stroud was known for producing fine woollen cloth, the town of Worsted became synonymous with a type of yarn; Banbury and Essex were strongly associated with cheeses.

In the market economy, goods are ungraded and unbranded, so that consumers have relatively few opportunities to evaluate quality prior to consumption. Consequently, supervision of weights, measures, food quality and prices was a key consideration. In medieval society, regulations for such matters appeared initially at the local level. The Charter of Worcester, written between 884 and 901 provided for fines for dishonest trading, amongst other things. Such local regulations were codified in 15th century England in what became known as the Statute of Winchester. This document outlines the Assizes for 16 different trades, most of which were associated with markets – miller, baker, fisher, brewer, inn-keeper, tallow-chandler, weaver, cordwainer etc. For each trade, regulations covered such issues as fraud, prices, quality, weights and measures and so on. The assize was a formal codification of prior informal codes which had been practised for many years. The courts of assize were granted the power to enforce these regulations. The process of standardizing quality, prices and measures assisted markets to gain the confidence of buyers and made them more attractive to the public.

A sixteenth century commentator, John Leland, described particular markets as “celebrate,” “very good” and “quik,” and, conversely, as “poore,” “meane,” and “of no price.” Over time, some products became associated with particular places, providing customers with valuable information about the types of goods, their quality and their region of origin. In this way, markets helped to provide an early form of product branding. Gradually, certain market towns earned a reputation for providing quality produce. Today, traders and showmen jealously guard the reputation of these historic chartered markets. An 18th century commentator, Daniel Defoe visited Sturbridge fair in 1723 and wrote a lengthy description which paints a picture of a highly organised, vibrant operation which attracted large number of visitors from some distance away. “As for the people in the fair, they all universally eat, drink and sleep in their booths, and tents; and the said booths are so intermingled with taverns, coffee-houses, drinking-houses, eating-houses, cookshops &c, and all tents too, and so many butchers and higglers from all the neighbouring counties come in to the fair every morning, with beef, mutton, fowls, bread, cheese, eggs and such things; and go with them from tent to tent and from door to door, that there is no want of provision of any kind, either dress’d or undress’d.”

In Asia Minor

The Grand Bazaar in Istanbul, one of the oldest continuously operating market buildings in existence; it houses approximately 3600 retail shops

In the Asia Minor, prior to the 10th century, market places were situated on the perimeter of the city. Along established trade routes, markets were most often associated with the caravanserai typically situated just outside the city walls. However, when the marketplace began to become integrated into city structures, it was transformed into a covered area where traders could buy and sell with some protection from the elements. Markets at Mecca and Medina were known to be significant trade centres in the 3rd century (CE) and the nomadic communities were highly dependent on them for both trade and social interactions. The Grand Bazaar in Istanbul is often cited as the world’s oldest continuously operating, purpose-built market; its construction began in 1455.

In Asia

|

This section needs expansion with: markets in other Asian countries besides China. You can help by adding to it. (June 2021)

|

A bas-relief of the Bayon temple depicting a 12th-century Khmer marketplace

Dating the emergence of marketplaces in China is difficult. According to tradition, the first market was established by the legendary Shennongan or the “Divine Farmer” who arranged for markets to be held at midday. In other ancient sayings, markets originally developed around wells in the town or village centre. Scholars, however, question the reliability of traditional narratives unless backed by archaeological evidence.

The earliest written references to markets dates to the time of Qi Huanggong (ruled 685 to 643 BCE). Qi’s Prime Minister, the great reformer, Guan Zhong, divided the capital into 21 districts (xiang) of which three were dedicated to farmers, three to hand-workers and three to businessmen, who were instructed to settle near the markets. Some of these early markets have been the subject of archaeological surveys. For instance, the market at Yong, the capital of the Qi state, measured 3,000 square metres and was an outdoor market.

According to the Rites of Zhou, markets were highly organized and served different groups at different times of day; merchants at the morning market, every day people at the afternoon market and peddlers at the evening market. The marketplace also became the place were executions were carried out, rewards were published and decrees were read out.

During the Qin empire and the Han dynasty which followed it, markets were enclosed with walls and gates and strictly separated from residential areas. Vendors were arranged according to the type of commodity offered, and markets were strictly regulated with departments responsible for security, weights and measures, price-fixing and certificates.

Over time, specialised markets began to emerge. In Luoyang, during the Tang Dynasty, a metal market was known. Outside the city walls were sheep and horse markets. Marco Polo’s account of 13th century markets specifically mentions a silk market. He was also impressed by the size of markets. According to his account, the ten markets of Hangzhou, primarily a fish market, attracted 40,000 to 50,000 patrons on each of its three trading days each week.

In China, negative attitudes towards mercantile activity developed; merchants were the lowest class of society. High officials carefully distanced themselves from merchant classes. In 627, an edict prohibited those of rank five or higher from entering markets. One anecdote from the time of Empress Wu relates the tale of a fourth rank official who missed out on the opportunity for promotion after he was seen purchasing a steamed pancake from a market.

In Mesoamerica

A model of an Aztec tianguis, National Museum of Anthropology

In Mesoamerica, a tiered system of traders developed independently. Extensive trade networks predated the Aztec empire by at least hundreds of years. Local markets where people purchased their daily necessities were known as tianguis, while a pochteca was a professional merchant who travelled long distances to obtain rare goods or luxury items desired by the nobility. The system supported various levels of pochteca – from very high status through to minor traders who acted as a type of peddler to fill in gaps in the distribution system. Colonial sources also record Mayan market hubs at Acalan, Champotón, Chetumal, Bacalar, Cachi, Conil, Pole, Cozumel, Cochuah, Chauaca, Chichén Itzá as well as markets marking the edges of Yucatecan canoe trade such as Xicalanco and Ulua. The Spanish conquerors commented on the impressive nature of the local markets in the 15th century. The Mexica (Aztec) market of Tlatelolco was the largest in all the Americas and said to be superior to those in Europe.

Types

A market place in Sortavala, Karelia

There are many different ways to classify markets. One way is to consider the nature of the buyer and the market’s place within the distribution system. This leads to two broad classes of market, namely retail market or wholesale markets. The economist, Alfred Marshall classified markets according to time period. In this classification, there are three types of market; the very short period market where the supply of a commodity remains fixed. Perishables, such as fruit, vegetables, meat and fish fall into this group since goods must be sold within a few days and the quantity supplied is relatively inelastic. The second group is the short period market where the time in which the quantity supplied can be increased by improving the scale of production (adding labor and other inputs but not by adding capital). Many non-perishable goods fall into this category. The third category is the long-period market where the length of time can be improved by capital investment.

Other ways to classify markets include its trading area (local, national or international); its physical format or its produce.

Major physical formats of markets are:

- Bazaar: typically a covered market in the Middle East

- Car boot sale – a type of market where people come together to trade household and garden goods; very popular in the United Kingdom

- Dry market: a market selling durable goods such as fabric and electronics as distinguished from “wet markets”

- E-commerce: an online marketplace for consumer products which can be sold anywhere in the world

- Indoor market of any sort

- Marketplace: an open space where a market is or was formerly held in a town

- Market square in Europe: open area usually in town centre with stalls selling goods in a public square

- Public market in the United States: an indoor, fixed market in a building and selling a variety of goods

- Street market: a public street with stalls along one or more sides of the street

- Floating market: where goods are sold from boats, chiefly found in Thailand, Indonesia and Vietnam

- Night market: popular in many countries in Asia, opening at night and featuring much street food and a more leisurely shopping experience. In Indonesia and Malaysia they are known as pasar malam

- Wet market (also known as a public market): a market selling fresh meat, fish, produce, and other perishable goods as distinguished from “dry markets”

Markets may feature a range of merchandise for sale, or they may be one of many specialist markets, such as:

- Animal markets (i.e. livestock markets)

- Antique markets

- Farmers’ markets, focusing on fresh produce and gourmet food lines (preserves, chutneys, relishes, cheeses etc.) prepared from farm produce

- Fish markets

- Flea markets or swap meets, a type of bazaar that rents space to people who want to sell or barter merchandise. Used goods, low quality items, and high quality items at low prices are commonplace

- Flower markets, such as the Mercado Jamaica in Mexico City and the Bloemenmarkt in Amsterdam

- Food halls, featuring gourmet food to consume on- and off-premises, such as those at Harrods (London) and Galeries Lafayette (Paris) department stores. In North America, these may be also referred to simply as “markets” (or “mercados” in Spanish), such as the West Side Market in Cleveland, Ponce City Market in Atlanta, and the Mercado Roma in Mexico City.

- Grey market: where second hand or recycled goods are sold (sometimes termed a green market)

- Handicraft markets

- Markets selling items used in the occult (for magic, by witches, etc.)

- Supermarkets and hypermarkets

-

Livestock market at Schaufschod, 2009

-

Bazaar: Grand Bazaar, Istanbul, Turkey

-

Marketplace: Main Market Square, Kraków, Poland: Europe’s largest medieval town square

-

Floating market: Damnoen Saduak floating market in Ratchaburi, Thailand, is a famous tourist attraction.

-

Night market: Shilin Night Market, Taiwan

-

Wet market in Hong Kong

-

Flea market in Germany

-

Wet market in Singapore

-

Fish market Jagalchi Busan

-

Crafts Village Market, Mexico

-

Mallick Ghat Flower Market, Kolkata, India

-

Harrods Food Hall, London, England

In literature and art

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paintings of markets. |

Vegetable seller at the market place by Pieter Aertsen, 1567

Markets generally have featured prominently in artworks, especially amongst the Dutch painters of Antwerp from the middle of the 16th century. Pieter Aertsen was known as the “great painter of the market.” Both he and his nephew, Joachim Beuckelaer, painted market scenes, street vendors and merchants extensively. Elizabeth Honig argues that painters’ interest in markets was in part due to the changing nature of the market system at that time. The public began to distinguish between two types of merchant, the meerseniers which referred to local merchants including bakers, grocers, sellers of dairy products and stall-holders, and the koopman‘, which described a new, emergent class of trader who dealt in goods or credit on a large scale. With the rise of a European merchant class, this distinction was necessary to separate the daily trade that the general population understood from the rising ranks of traders who operated on a world stage and were seen as quite distant from everyday experience.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, as Europeans conquered parts of North Africa and the Levant, European artists began to visit the Orient and painted scenes of everyday life. Europeans sharply divided peoples into two broad groups – the European West and the East or Orient; us and the other. Europeans often saw Orientals as the photographic negative of Western civilisation; the peoples could be threatening- they were “despotic, static and irrational whereas Europe was viewed as democratic, dynamic and rational.” At the same time, the Orient was seen as exotic, mysterious, a place of fables and beauty. This fascination with the other gave rise to a genre of painting known as Orientalism. Artists focussed on the exotic beauty of the land – the markets and bazaars, caravans and snake charmers. Islamic architecture also became favourite subject matter, and the high vaulted market places features in numerous paintings and sketches.

Individual markets have also attracted literary attention. Les Halles was known as the “Belly of Paris”, and was so named by author, Émile Zola in his novel Le Ventre de Paris, which is set in the busy 19th century marketplace of central Paris. Les Halles, a complex of market pavilions in Paris, features extensively in both literature and painting. Giuseppe Canella (1788 – 1847) painted Les Halles et la rue de la Tonnellerie. Photographer, Henri Lemoine (1848 – 1924), also photographed Les Halles de Paris.

Around the world

|

|

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021)

|

Africa

Markets have been known in parts of Africa for centuries. An 18th century commentator noted the many markets he visited in West Africa. He provided a detailed description of market activities at Sabi, in the Wydah, (now the part of the Republic of Benin):

- “Their fairs and markets are regulated with so much care and prudence, that nothing contrary to law is ever committed. All sorts of merchandise here are collected, and those who have brought goods are permitted to take what time they please to dispose of them, but without fraud or noise. A judge, attended by four officers armed, is appointed by the King for the inspection of goods, to hear and determine all grievances, complaints and disputes… The market place is surrounded by butlers and booths, and places of refreshment for the conveniency of the people. They are only permitted to sell certain sorts of meats, pork, goats, beef and dog flesh. Other booths are kept by women who sell maize, millet, rice and corn bread. Other shops sell Pito, a sort of pleasant and wholesome, and very refreshing beer. Palm wine, acqua vita and spirits which they get from the Europeans, are kept in other shops, with restrictions on sale to prevent drunkenness and riots. Here slaves of both sexes are bought and sold, also oxen, sheep, dogs, hogs, shish and birds of all kind. Woollen cloths, linen, silks and calicoes of European and Indian manufacture, they have it in great abundance, likewise hard-ware, china and glass of all sorts; gold in dust and ingots, iron in bars, lead in sheets and everything of European, Asiatic or African production is here found at reasonable prices.”

In the Kingdom of Benin (modern Benin City), he commented on the exotic foods available for sale at a market there:

- ” Besides the dry merchandise of which the markets of Benin abound, they are also well stocked with eatables, a little particular in kind. Here they expose dogs to sale for eating, of which the negroes are very fond. Roasted monkeys, apes and baboons are every where to be seen. Bats, rats and lizards dried in the sun, palm wine and fruit, form the must luxurious entertainments, and stand continually for sale in the streets.”

Botswana

The sale of agricultural produce to the formal market is largely controlled by large corporations. Most small, local farmers sell their produce to the informal market, local communities and street vendors. The main wholesale market is the Horticultural market in Gaborone. The government made some attempts to build markets in the north of the country, but that was largely unsuccessful and most commercial buyers travel to Johannesburg or Tshwane for supplies.

Ethiopia

Ethiopia is a major producer and exporter of grains and a number of wholesale markets assist with the distribution and export of such products. Important wholesale markets include: Nekemte in the East Welega zone, Jimma in the Jimma zone, Assela and Sagure in the Arsi zone, Bahir Dar and Bure in the Gojjam zone, Dessie and Kombolcha in the Wollo zone, Mekele in the Tigray region, Dire Dawa and Harar in the Oromia region, and Addis Ababa. Some of the major retail markets in Ethiopia include: Addis Mercato in Addis Ababa, the largest open air market in the country; Gulalle and Galan, both in Addis Ababa; Awasa Lake Fish Market in Awasa, the Saturday market Harar, and the Saturday market in Axum.

-

Addis Mercato, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

-

Awasa fish market, Awasa, Ethiopia

-

Adigrat Market, Ethiopia

-

Konso Sorghum Market, Ethiopia

-

Street Market, Harar, Ethiopia

Ghana

Ghanaian markets have survived in spite of sometimes brutal measures to eradicate them. In the late 1970s, the Ghanaian government used market traders as a scapegoat for its own policy failures which involved food shortages and high inflation. The government blamed traders for failing to observe pricing guidelines and vilified “women merchants”. In 1979, the Makola market was dynamited and bulldozed, but within a week the traders were back selling fruit, vegetables and fish, albeit without a roof over their head.

-

Kumasi Market in Ghana

-

Market between Accra and Cape Coast, Ghana

-

Madina Ghana Market

-

Market in Anaynui, Ghana

-

Street Outside Makola Market, Accra, Ghana

Kenya

Kenya’s capital, Nairobi, has several major markets. Wakulima market is one of the region’s largest markets, situated on Haile Selassie Avenue in Nairobi. Other markets in Nairobi are: Kariakor Market Gikomba Market and Muthurwa market In Mombasa, Kongowea market is also a very large market with over 1500 stalls and covering 4.5 ha.

-

Mombasa Market

-

Wakulima market, Nairobi

-

Masai Market, Nairobi

-

Kilingili Market

Morocco

In Morocco, markets are known as souks, and are normally found in a city’s Medina (old city or old quarter). Shopping at a produce market is a standard feature of daily life in Morocco. In the larger cities, Medinas are typically made up of a collection of souks built amid a maze of narrow streets and laneways where independent vendors and artisans tend to cluster in sections which subsequently become known for a particular type of produce – such as the silversmith’s street or the textile district. In Tangiers, a sprawling market fills the many streets of the medina and this area is divided into two sections, known as the Grand Socco and the Petit Socco. The term ‘socco’ is a Spanish corruption of the Arabic word for souk, meaning marketplace. These markets sell a large variety of goods; fresh produce, cooking equipment, pottery, silverware, rugs and carpets, leather goods, clothing, accessories, electronics alongside cafes, restaurants and take-away food stalls. The Medina at Fez is the oldest, having been founded in the 9th century. The Medina at Fez has been named a World Heritage site. Today it is the main fresh produce market and is noted for its narrow laneways and for a total ban on motorized traffic. All produce is brought in and out of the marketplace by donkey or hand-cart. In Marrakesh, the main produce markets are also to be found in the Medina and a colourful market is also held daily in the Jemaa el-Fnaa (main square) where roaming performers and musicians entertain the large crowds that gather there. Marrakesh has the largest traditional Berber market in Morocco.

-

Market stalls in Tangiers’ medina

-

Spice shop in Tangiers’ medina

-

Market scene, Tangiers

-

Berber woman selling produce at a Moroccan market

-

Jemaa el-Fnaa at night

Namibia

Namibia has been almost entirely dependent on South Africa for its fresh produce. Dominated by rolling plains and long sand dunes and an unpredictable rainfall, many parts of Namibia are unsuited to growing fruit and vegetables. Government sponsored initiatives have encouraged producers to grow fresh fruit, vegetables, legumes and grains The Namibian Ministry of Agriculture has recently launched a system of fresh produce hubs to serve as a platform for producers to market and distribute their produce. It is anticipated that these hubs will assist in curbing the number of sellers who take their produce to South Africa where it is placed on cold storage, only to be imported back into the country at a later date.

-

Market Scene Oshakati Namibia

-

Street Market in Namibia, Windhoek

-

Artisans’ Market, Swakopmund

-

Artisan’s market, d’Okahandja

-

Oshakati New market, 2016

Nigeria

South Africa

Fresh produce markets have traditionally dominated the South African food chain, handling more than half of all fresh produce. Although large, vertically integrated food retailers, such as supermarkets, are beginning to make inroads into the supply chain, traditional hawkers and produce markets have shown remarkable resilience. The main markets in Johannesburg are: Jozi Real Food Market, Bryanston Organic Market, Pretoria Boeremark specialising in South African delicacies, Hazel Food Market, Panorama Flea Market, Rosebank Sunday Market, Market on Main – a periodic arts market and Neighbourhood Markets.

The Gambia

The “Gambia is Good” initiative was established in 2004 with a view to encouraging a market for locally grown fresh produce rather than imported ones. The plan was designed to “stimulate local livelihoods, inspire entrepreneurship and reduce the environmental and social cost of imported produce.”

A great deal of the produce trade is carried out informally on street corners and many shops are little more than market booths. However, dedicated open air and covered markets can be found in the larger towns. Notable markets include: the Serekunda Market in Gambia’s largest city, Serekunda, which opens from early morning to late at night 7 days a week and trades in produce, live animals, clothing, accessories, jewellery, crafts, second hand goods and souvenirs; The Albert Market in the capital, Banjul which sells fresh produce, colourful, locally designed fabrics, musical instruments, carved wooden masks and other local products. Other interesting markets include: Bakau Fish Market in Bakau; Tanji Fish Market, Tanji, where brightly painted fishing boats bring in the fish from where it is immediately preserved using traditional methods and prepared for distribution to other West African countries; The Woodcarvers Market in Brikama which boasts the largest concentration of woodcarvers in the country; the Pottery Market in Basse Santa; the Atlantic Road Craft Market at Bakau and the Senegambia Craft Market at Bakau.

-

Serekunda Market, Serekunda, The Gambia

-

Vendor at Serekunda Market, The Gambia

-

The Albert Market, Banjul, The Gambia

-

Tanji Fish Market, Tanji, The Gambia

-

Traditional wood carvings at a market in The Gambia

Uganda

- Nakawa Market

Asia

Produce markets in Asia are undergoing major changes as supermarkets enter the retail scene and the growing middle classes acquire preferences for branded goods. Many supermarkets purchase directly from producers, supplanting the traditional role of both wholesale and retail markets. In order to survive, produce markets have been forced to consider value adding opportunities and many retail markets now focus on ready-to-eat food and take-away food.

East Asia

China

In China, the existence of street and wet markets has been known for centuries, however, many of these were restricted in the 1950s and 60s and only permitted to re-open in 1978. The distinction between wholesale and retail markets is somewhat ambiguous in China, since many markets serve both as distribution centres and retail shopping venues. To assist in the distribution of food, more than 9,000 wholesale produce markets operate in China. Some of these markets operate on a very large scale. For example, Beijing’s Xinfadi Wholesale market, currently under renovation, is expected to have a footprint of 112 hectares when complete. The Beijing Zoo Market (retail market) is a collection of 12 different markets, comprising some 20,000 tenant stall-holders, 30,000 employees and more than 100,000 customers daily.

China is both a major importer and exporter of fruit and vegetables and is now the world’s largest exporter of apples. In addition to produce markets, China has many specialised markets such as a silk market, clothing markets and an antiques market. China’s fresh produce market is undergoing major change. In the larger cities, purchasing is gradually moving to online with door-to-door deliveries.

Some of the more important markets in China include:

- Wholesale produce market: Xinfadi (wholesale produce market, Beijing) – with an annual turnover volume of 14 million tonnes of meat, fruit and vegetables, it supplies 70 percent of Beijing’s vegetables and Nanzhan (Shenyang, Liaoning) which supplies the northern provinces.

- Retail produce markets: The Fresh Produce Market at Hutong market (Beijing); Xiabu Xiabu market (Beijing), Panjiayuan market (Beijing); Dazhongsi market (Beijing), Tianyi market (Beijing), Beijing Zoo market, Dahongmen market (Fengtai District, Beijing), Sanyuanli market (Beijing), Shengfu Xiaoguan morning market (Beijing), Lishuiqiao seafood farmers’ market (Beijing), Wangjing Zonghe market (Beijing), Chaowai market (Beijing), Zhenbai market (Shanghai’s largest produce market)

-

Hui vendors at Linxia City Market

-

Beijing silk market

-

Panjiayuan Market, Beijing (exterior)

-

Panjiayuan Market, Beijing (external stallholder)

-

Panjiayuan Market, Beijing (interior)

-

Dunhuang market

Hong Kong

Hong Kong relies heavily imports to meet its fresh produce needs. Importers are consequently an important part of the distribution network, and some importers supply directly to retail consumers. Street markets in Hong Kong are held every day except on a few traditional Chinese holidays like Chinese New Year. Stalls opened at two sides of a street are required to have licenses issued by the Hong Kong Government. The various types of street markets include fresh foods, clothing, cooked foods, flowers and electronics. The earliest form of market was a Gaa si (wet market). Some traditional markets have been replaced by shopping centres, markets in municipal service buildings and supermarkets, while others have become tourist attractions such as Tung Choi Street and Apliu Street. The Central Market, Hong Kong is a grade II listed building.

Japan

- Tsukiji fish market

- Kochi Sunday Market

- Hirome Ichiba

South Korea

Although the majority of markets in South Korea are wholesale markets, retail customers are permitted to make purchases in all of them. The Gwangjang Market is the nation’s top market and is a popular tourist destination.

Taiwan

Taiwan meets most of its produce needs through local production. This means that the country has a very active network of wholesale and retail markets. According to the Guardian newspaper, Taiwan has “the best night market scene in the world and some of the most exciting street food in Asia.”

South Asia

In South Asia, especially Nepal, India and Bangladesh, a Haat (also known as hat) refers to a regular rural produce market, typically held once or twice per week.

India

The marketing historian, Petty, has suggested that Indian marketplaces first arose during the Chola Dynasty (approx. 850 -1279CE) during a period of favourable economic conditions. Distinct types of markets were evident; Nagaaram (streets of shops, often devoted to specific types of goods; Angadi (markets) and Perangadi (large markets in the inner city districts).

The sub-continent may have borrowed the concept of covered marketplaces from the Middle East around the tenth century with the arrival of Islam. The caravanserai and covered market structures, known as suqs, first began to appear along the silk routes and were located in the area just outside the city perimeter. Following the tradition established on the Arabian peninsula, India also established temporary-seasonal markets in regional districts. In Rajasthan’s Pushkar, an annual camel market was first recorded in the 15th century. However, following the foundation of the Mughal Empire in northern India during the 16th century, this arrangement changed. A covered bazaar or market place became integrated into city structures and was to be found in the city centre. Markets and bazaars were well known in the colonial era. Some of these bazaars appear to have specialised in particular types of produce. The Patna district, in the 17th century, was home to 175 weaver villages and the Patna Bazaar enjoyed a reputation as a centre of trade in fine cloth. When the Italian writer and traveller, Niccolao Manucci, visited there in 1863, he found many merchants trading in cotton and silk in Patna’s bazaars.

In India today, many different types of market serve retail and commercial clients:

(1) Wholesale markets

-

- Primary wholesale markets: held once or twice per week, these sell produce from local villages e.g. Rice Bazaar at Thissur in Kerala

- Secondary wholesale markets (also known as mandis): smaller merchants purchase from primary markets and sell at secondary markets. A small number of primary producers may sell direct to mandis.

- Terminal markets: Markets that sell directly to the end-user, whether it be the consumer, food processor or shipping agent for export to foreign countries e.g. Bombay Terminal Market

(2) Retail markets

-

- Retail markets: spread across villages, towns and cities

- Fairs: held on religious days and deal in livestock and agricultural produce

In India (and also Bangladesh and Pakistan), a landa bazaar is a type of a bazaar or a marketplace with lowest prices where only secondhand general goods are exchanged or sold. A haat also refers to a bazaar or market in Bangladesh and Pakistan and the term may also be used in India. A saddar refers to the main, central market in a town while a mandi refers to a large marketplace. A Meena Bazaar is a marketplace where goods are sold in an effort to raise money for charity.

-

Magh Mela at Prayaga Sangam Uttar Pradesh India is a fair associated with the Sankranti Hindu festival

-

The Bombay Street Market is a terminal market

-

Goan sausages being sold at the Mapusa market, Goa, India

-