A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a country’s elections. It is common for the members of a political party to have similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or policy goals.

Political parties have become a major part of the politics of almost every country, as modern party organizations developed and spread around the world over the last few centuries. Some countries have only one political party while others have dozens, but it is extremely rare for a country to have no political parties. Parties are important in the politics of autocracies as well as democracies, though usually democracies have more political parties than autocracies. Autocracies often have a single party that governs the country, and some political scientists consider competition between two or more parties to be an essential part of democracy.

Parties can develop from existing divisions in society, like the divisions between lower and upper classes, and they streamline the process of making political decisions by encouraging their members to cooperate. Political parties usually include a party leader, who has primary responsibility for the activities of the party; party executives, who may select the leader and who perform administrative and organizational tasks; and party members, who may volunteer to help the party, donate money to it, and vote for its candidates. There are many different ways in which political parties can be structured and interact with the electorate. The contributions that citizens give to political parties are often regulated by law, and parties will sometimes govern in a way that favours the people who donate time and money to them.

Many political parties are motivated by ideological goals. It is common for democratic elections to feature competitions between liberal, conservative, and socialist parties; other common ideologies of very large political parties include communism, populism, nationalism, and Islamism. Political parties in different countries will often adopt similar colours and symbols to identify themselves with a particular ideology. However, many political parties have no ideological affiliation, and may instead be primarily engaged in patronage, clientelism, or the advancement of a specific political entrepreneur.

Definition

Political parties are collective entities that organize competitions for political offices.:3 The members of a political party contest elections under a shared label. In a narrow definition, a political party can be thought of as just the group of candidates who run for office under a party label.:3 In a broader definition, political parties are the entire apparatus that supports the election of a group of candidates, including voters and volunteers who identify with a particular political party, the official party organizations that support the election of that party’s candidates, and legislators in the government who are affiliated with the party.

Political parties are distinguished from other political groups and clubs, such as political factions or interest groups, mostly by the fact that parties are focused on electing candidates whereas interest groups are focused on advancing a policy agenda. This is related to other features that sometimes distinguish parties from other political organizations, including a larger membership, greater stability over time, and deeper connection to the electorate.

In many countries the notion of a political party is defined in law, and governments may specify requirements for an organization to legally qualify as a political party.

In some definitions of political parties, a party is an organization that advances a specific set of ideological or policy goals, or that organizes people whose ideas about politics are similar. However, many political parties are not primarily motivated by ideology or policy; for example, political parties can be mainly clientelistic or patronage-based organizations, or tools for advancing the career of a specific political entrepreneur.

History

The idea of people forming large groups or factions to advocate for their shared interests is ancient. Plato mentions the political factions of Classical Athens in the Republic, and Aristotle discusses the tendency of different types of government to produce factions in the Politics. Certain ancient disputes were also factional, like the Nika riots between two chariot racing factions at the Hippodrome of Constantinople. A few instances of recorded political groups or factions in history included the late Roman Republic’s Populares and Optimates faction as well as the Dutch Republic’s Orangists and the Staatsgezinde. However, modern political parties are considered to have emerged around the end of the 18th century; they are usually considered to have first appeared in Europe and the United States, with the United Kingdom’s Conservative Party, Poland’s Patriotic party and the Democratic Party of the United States all of which except for Poland’s are frequently called the world’s “oldest continuous political party”.

Before the development of mass political parties, elections typically featured a much lower level of competitiveness, had small enough polities that direct decision-making was feasible, and held elections that were dominated by individual networks or cliques that could independently propel a candidate to victory in an election.:510

18th century

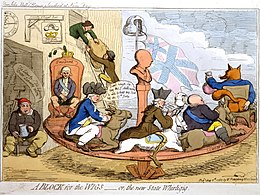

In A Block for the Wigs (1783), James Gillray caricatured Fox’s return to power in a coalition with North. George III is the blockhead in the centre.

Some scholars argue that the first modern political parties developed in early modern Britain in the 18th century, after the Exclusion Crisis and the Glorious Revolution.:4 The Whig faction originally organized itself around support for Protestant constitutional monarchy as opposed to absolute rule, whereas the conservative Tory faction (originally the Royalist or Cavalier faction of the English Civil War) supported a strong monarchy, and these two groups structured disputes in the politics of the United Kingdom throughout the 18th century:4 The Rockingham Whigs have been identified as the first modern political party, because they retained a coherent party label and motivating principles even while out of power.

At the end of the late 18th century, the United States also developed a party system, called the First Party System. Although the framers of the 1787 United States Constitution did not all anticipate that American political disputes would be primarily organized around political parties, political controversies in the early 1790s over the extent of federal government powers saw the emergence of two proto-political parties: the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party.

19th century

By the early 19th century, a number of countries had developed stable modern party systems. The party system that developed in Sweden has been called the world’s first party system, on the basis that previous party systems were not fully stable or institutionalized. In many European countries, including Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, and France, political parties organized around a liberal-conservative divide, or around religious disputes.:510 The spread of the party model of politics was accelerated by the 1848 Revolutions around Europe.

The strength of political parties in the United States waned during the Era of Good Feelings, but shifted and strengthened again by the second half of the 19th century. By the end of the 19th century, the Irish political leader Charles Stewart Parnell had implemented several methods and structures that would come to be associated with strong grassroots political parties, such as explicit party discipline.

20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century in Europe, the liberal-conservative divide that characterized most party systems was disrupted by the emergence of socialist parties, which attracted the support of organized trade unions.:511

During the wave of decolonization in the mid-20th century, many newly sovereign countries developed party systems that often emerged out of their movements for independence. For example, a system of political parties arose out of factions in the Indian independence movement, and was strengthened and stabilized by the policies of Indira Gandhi in the 1970s.:165 The formation of the Indian National Congress, which developed in the early 20th century as a pro-independence faction in British India and immediately became a major political party after Indian independence, foreshadowed the dynamic in many newly independent countries; for example, the Uganda National Congress was a pro-independence party and the first political party in Uganda, and its name was chosen as an homage to the Indian National Congress. A similar pattern occurred in many countries at the end of colonial periods.

Why political parties exist

Political parties are a nearly ubiquitous feature of modern countries. Nearly all democratic countries have strong political parties, and many political scientists consider countries with fewer than two parties to necessarily be autocratic. However, these sources allow that a country with multiple competitive parties is not necessarily democratic, and the politics of many autocratic countries are organized around one dominant political party. The ubiquity and strength of political parties in nearly every modern country has led researchers to remark that the existence of political parties is almost a law of politics, and to ask why parties appear to be such an essential part of modern states.:510 Political scientists have therefore come up with several explanations for why political parties are a nearly universal political phenomenon.:11

Social cleavages

Political parties like the Romanian Communist Party can arise out of, or be closely connected to, existing segments of society, such as organizations of workers.

One of the core explanations for why political parties exist is that they arise from pre-existing divisions among people: society is divided in a certain way, and a party is formed to organize that division into electoral competition. By the 1950s, economists and political scientists had shown that party organizations can take advantage of the distribution of voters’ preferences over political issues, adjusting themselves in response to what voters believe in order to become more competitive. Beginning in the 1960s, academics began identifying the social cleavages in different countries that might have given rise to specific parties, such as religious cleavages in specific countries that may have produced religious parties there.

The theory that parties are produced by social cleavages has drawn several criticisms. Some authors have challenged it on empirical grounds, either finding no evidence for the claim that parties emerge from existing cleavages, or arguing that the claim is not empirically testable. Others note that while social cleavages might cause political parties to exist, this obscures the opposite effect: that political parties also cause changes in the underlying social cleavages.:13 A further objection is that, if the explanation for where parties come from is that they emerge from existing social cleavages, then the theory is an incomplete story of where political parties come from unless it also explains where social cleavages come from. But origins of social cleavages have also been proposed: one argument is that social cleavages are formed by historical conflicts.

Individual and group incentives

It is easier for voters to evaluate one simple list of policies for each party, like this platform for the United Australia Party, than to individually judge every single candidate.

An alternative explanation for why parties are ubiquitous across the world is that the formation of parties provides compatible incentives for candidates and legislators. For example, the existence of political parties might coordinate candidates across geographic districts, so that a candidate in one electoral district has an incentive to assist a similar candidate in a different district. So political parties can be mechanisms for preventing candidates with similar goals from acting to each other’s detriment when campaigning or governing. This might help explain the ubiquity of parties because, if a group of candidates form a party and are harming each other less, they may perform better over the long run than unaffiliated politicians, so politicians with party affiliations will out-compete politicians without parties.

Parties can also align their member’s incentives when those members are in a legislature. The existence of a party apparatus can help coalitions of electors to agree on ideal policy choices, whereas a legislature of unaffiliated members might never be able to agree on a single best policy choice without some institution constraining their options.

Parties as heuristics

Another prominent explanation for why political parties exist is psychological: parties may be necessary for many individuals to participate in politics because they provide a massively simplifying heuristic, which allows people to make informed choices with much less mental effort. Without political parties, electors would have to individually evaluate every candidate in every election. But political parties enable electors to make judgments about just a few groups, and then apply their judgment of the party to all the candidates affiliated with that group. Because it is much easier to become informed about a few parties’ platforms than about many candidates’ personal positions, parties reduce the cognitive burden for people to cast informed votes. However, evidence suggests that over the last several decades the strength of party identification has been weakening, so this may be a less important function for parties to provide than it was in the past.

Structure of political parties

Political parties are often structured in similar ways across countries. They typically feature a single party leader, a group of party executives, and a community of party members. Parties in democracies usually select their party leadership in ways that are more open and competitive than parties in autocracies, where the selection of a new party leader is likely to be tightly controlled. In countries with large sub-national regions, particularly federalist countries, there may be regional party leaders and regional party members in addition to the national membership and leadership.:75

Party leaders

A National Congress of the Communist Party of China, where policies may be set and changes can be made to party leadership.

Parties are typically led by a party leader, who is the main representative of the party and often has primary responsibility for overseeing the party’s policies and strategies. The leader of the party that controls the government usually becomes the head of government, such as the president or prime minister, and the leaders of other parties explicitly compete to become the head of government. In both presidential democracies and parliamentary democracies, the members of a party frequently have substantial input into the selection of party leaders, for example by voting on party leadership at a party conference. Because the leader of a major party is a powerful and visible person, many party leaders are well-known career politicians. Party leaders can be sufficiently prominent that they affect how voters perceive the entire political party, and some voters decide how to vote in elections partly based on how much they like the leaders of the different parties.

The number of people involved in choosing party leaders varies widely across parties and countries. On one extreme, party leaders might be selected from the entire electorate; on the opposite extreme, they might be selected by just one individual. Selection by a smaller group can be a feature of party leadership transitions in more autocratic countries, where the existence of political parties may be severely constrained to only one legal political party, or only one competitive party. Some of these parties, like the Chinese Communist Party, have rigid methods for selecting the next party leader, which involve selection by other party members. A small number of single-party states have hereditary succession, where party leadership is inherited by the child of an outgoing party leader. Autocratic parties use more restrictive selection methods to avoid having major shifts in the regime as a result of successions.

Party executives

In both democratic and non-democratic countries, the party leader is often the foremost member of a larger party leadership. A party executive will commonly include administrative positions, like a party secretary and a party chair, who may be different people from the party leader. These executive organizations may serve to constrain the party leader, especially if that leader is an autocrat. It is common for political parties to conduct major leadership decisions, like selecting a party executive and setting their policy goals, during regular party conferences.

Members of the National Woman’s Party in 1918.

Much as party leaders who are not in power are usually at least nominally competing to become the head of government, the entire party executive may be competing for various positions in the government. For example, in Westminster systems, the largest party that is out of power will form the Official Opposition in parliament, and select a shadow cabinet which (among other functions) provides a signal about which members of the party would hold which positions in the government if the party were to win an election.

Party membership

Citizens in a democracy will often affiliate with a political party. Party membership may include paying dues, an agreement not to affiliate with multiple parties at the same time, and sometimes a statement of agreement with the party’s policies and platform. In democratic countries, members of political parties often are allowed to participate in elections to choose the party leadership. Party members may form the base of the volunteer activists and donors who support political parties during campaigns. The extent of participation in party organizations can be affected by a country’s political institutions, with certain electoral systems and party systems encouraging higher party membership. Since at least the 1980s, membership in large traditional party organizations has been steadily declining across a number of countries.

Types of party organizations

Political scientists have distinguished between different types of political parties that have evolved throughout history. These include cadre parties, mass parties, catch-all parties and cartel parties.:163–178 Cadre parties were political elites that were concerned with contesting elections and restricted the influence of outsiders, who were only required to assist in election campaigns. Mass parties tried to recruit new members who were a source of party income and were often expected to spread party ideology as well as assist in elections. In the United States, where both major parties were cadre parties, the introduction of primaries and other reforms has transformed them so that power is held by activists who compete over influence and nomination of candidates.

Cadre parties

A cadre party, or elite party, is a type of political party that was dominant in the nineteenth century before the introduction of universal suffrage and that was made up of a collection of individuals or political elites. The French political scientist Maurice Duverger first distinguished between “cadre” and “mass” parties, founding his distinction on the differences within the organisational structures of these two types.:60–71 Cadre parties are characterized by minimal and loose organisation, and are financed by fewer larger monetary contributions typically originating from outside the party. Cadre parties give little priority to expanding the party’s membership base, and its leaders are its only members.:165 The earliest parties, such as the early American political parties, the Democratic-Republicans and the Federalists, are classified as cadre parties.

Mass parties

Parties can arise from existing cleavages in society, like the Social Democratic Party of Germany which was formed to represent German workers.

A mass party is a type of political party that developed around cleavages in society and mobilized the ordinary citizens or ‘masses’ in the political process. In Europe, the introduction of universal suffrage resulted in the creation of worker’s parties that later evolved into mass parties; an example is the German Social Democratic Party.:165 These parties represented large groups of citizens who had previously not been represented in political processes, articulating the interests of different groups in society. In contrast to cadre parties, mass parties are funded by their members, and rely on and maintain a large membership base. Further, mass parties prioritize the mobilization of voters and are more centralized than cadre parties.

Catch-all parties

The term “Catch-all party” was developed by German-American political scientist Otto Kirchheimer to describe the parties that developed in the 1950s and 1960s as a result of changes within the mass parties.:165 The term “big tent party” may be used interchangeably. Kirchheimer characterized the shift from the traditional mass parties to catch-all parties as a set of developments including the “drastic reduction of the party’s ideological baggage” and the “downgrading of the role of the individual party member”. By broadening their central ideologies into more open-ended ones, catch-all parties seek to secure the support of a wider section of the population. Further, the role of members is reduced as catch-all parties are financed in part by the state or by donations.:163–178 In Europe, the shift of Christian Democratic parties that were organized around religion into broader centre-right parties epitomizes this type.

Cartel parties

Cartel parties are a type of political party that emerged post-1970s and are characterized by heavy state financing and the diminished role of ideology as an organizing principle. The cartel party thesis was developed by Richard Katz and Peter Mair who wrote that political parties have turned into “semi-state agencies”, acting on behalf of the state rather than groups in society. The term ‘cartel’ refers to the way in which prominent parties in government make it difficult for new parties to enter, as such forming a cartel of established parties. As with catch-all parties, the role of members in cartel parties is largely insignificant as parties use the resources of the state to maintain their position within the political system.:163–178

Niche parties

A political party may focus on one niche issue, like the environment.

Niche parties are a type of political party that developed on the basis of the emergence of new cleavages and issues in politics, such as immigration and the environment. In contrast to mainstream or catch-all parties, niche parties articulate an often limited set of interests in a way that does not conform to the dominant economic left-right divide in politics, emphasising issues that do not attain prominence within the other parties. Further, niche parties do not respond to changes in public opinion to the extent that mainstream parties do. Examples of niche parties include Green parties and extreme nationalist parties, such as the Front National in France. However, over time these parties may lose some of their niche qualities, instead adopting those of mainstream parties, for example after entering government.

Entrepreneurial parties

Entrepreneurial parties are a type of political party that is centered on a political entrepreneur, and dedicated to the advancement of that person or their policies.

Party positions and ideologies

Ideology of ruling party in legislative body at the regional or national level worldwide, or ideology of ruling body, as of May 2020. Colour-coded from left- (red) to right- (blue) wing scale. Based on identification from international recognition or self-proclaimed party ideology.

Political ideologies are one of the major organizing features of political parties, and parties often officially align themselves with specific ideologies. Parties adopt ideologies for a number of reasons. Ideological affiliations for political parties send signals about what sort of policies they might pursue if they were in power. Ideologies also differentiate parties from one another, so that voters can select the party that advances the policies that they most prefer. A party may also seek to advance an ideology, by convincing voters to adopt its belief system.

Common ideologies that can form a central part of the identity of a political party include liberalism, conservatism, socialism, communism, anarchism, fascism, feminism, environmentalism, nationalism, fundamentalism, Islamism, and multiculturalism. Liberalism is the ideology that is most closely connected to the history of democracies and is often considered to be the dominant or default ideology of governing parties in much of the contemporary world. Many of the traditional competitors to liberal parties are conservative parties. Socialist, communist, anarchist, fascist, and nationalist parties are more recent developments, largely entering political competitions only in the 19th and 20th centuries. Feminism, environmentalism, multiculturalism, and certain types of fundamentalism became prominent towards the end of the 20th century.

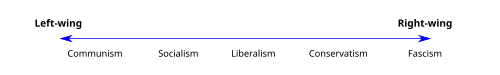

Parties can sometimes be organized according to their ideology using an economic left–right political spectrum. However, a simple left-right economic axis does not fully capture the variation in party ideologies. Other common axes that are used to compare the ideologies of political parties include ranges from liberal to authoritarian, from pro-establishment to anti-establishment, and from tolerant to pluralistic.

Though ideologies are central to a large number of political parties around the world, not all political parties have an organizing ideology, or exist to promote ideological policies. For example, some political parties may be clientelistic or patronage-based organizations, which are largely concerned with distributing goods. Other political parties may be created as tools for the advancement of an individual politician. Either of these types of parties may also be ideological, but parties can exist which are not ideological.

Party systems

Political parties are ubiquitous across both democratic and autocratic countries, and there is often very little change in which political parties have a chance of holding power in a country from one election to the next. This makes it possible to think about the political parties in a country as collectively forming one of the country’s central political institutions, called a party system. Some basic features of a party system are how many parties there are and what sorts of parties are the most successful. These properties are closely connected to other major features of the country’s politics, like how democratic it is, what sorts of restrictions its laws impose on political parties, and what type of electoral systems it uses. An informative way to classify the party systems of the world is by how many parties they include. Because some party systems include a large number of parties that have a very low probability of winning elections, it is often useful to think about the effective number of parties (the number of parties weighted by the strength of those parties) rather than the literal number of registered parties.

Non-partisan systems

In a non-partisan legislature, like the Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories, every member runs and legislates as a political independent with no party affiliation.

In a non-partisan system, no political parties exist, or political parties are not a major part of the political system. There are very few countries without political parties. A permanent absence of parties is usually, but not always, the result of an official ban on partisan activity. A temporary lack of partisan activity can also occur during an upheaval in a country’s politics.

In some non-partisan countries, the formation of parties is explicitly banned by law. The existence of political parties may be banned in autocratic countries in order to prevent a turnover in power. For example, in Saudi Arabia, a ban on political parties has been used as a tool for protecting the monarchy. However, parties are also banned in some polities that have long democratic histories, usually in local or regional elections of countries that have strong national party systems.

Political parties may also temporarily cease to exist in countries that have either only been established recently, or have experienced a major upheaval in their politics and have not yet returned to a stable system of political parties. For example, the United States began as a non-partisan democracy, and it evolved a stable system of political parties over the course of many decades.:ch.4 A country’s party system may also dissolve and take time to re-form, leaving a period of minimal or no party system, such as in Peru following the regime of Alberto Fujimori. However, it is also possible (though rare) for countries with no bans on political parties, and which have not experienced a major disruption, to nevertheless have no political parties: there are a small number of pacific island democracies, such as Palau, where political parties are permitted to exist and yet parties are not an important part of national politics.

One-party systems

In a one-party system, power is held entirely by one political party. When only one political party exists, it may be the result of a ban on the formation of any competing political parties, which is a common feature in authoritarian states. For example, the Communist Party of Cuba is the only permitted political party in Cuba, and is the only party that can hold seats in the legislature. When only one powerful party is legally permitted to exist, its membership can grow to contain a very large portion of society and it can play substantial roles in civil society that are not necessarily directly related to political governance; one example of this is the Chinese Communist Party. Bans on competing parties can also ensure that only one party can ever realistically hold power, even without completely outlawing all other political parties. For example, in North Korea, more than one party is officially permitted to exist and even to seat members in the legislature, but laws ensure that the Workers’ Party of Korea retains control.

It is also possible for countries with free elections to have only one party that holds power. These cases are sometimes called dominant-party systems or particracies. Scholars have debated whether or not a country that has never experienced a transfer of power from one party to another can nevertheless be considered a democracy.:23 There have been periods of government exclusively or entirely by one party in some countries that are often considered to have been democratic, and which had no official legal barriers to the inclusion of other parties in the government; this includes recent periods in Botswana, Japan, Mexico, Senegal, and South Africa.:24–27 It can also occur that one political party dominates a sub-national region of a democratic country that has a competitive national party system; one example is the southern United States during much of the 19th and 20th centuries, where the Democratic Party had almost complete control.

Two-party systems

The United States has one of the main examples of a two-party system.

In several countries, there are only two parties that have a realistic chance of competing to form government. One canonical two-party democracy is the United States, where the national government is exclusively controlled by either the Democratic Party and the Republican Party. Other examples of countries which have had long periods of two-party dominance include Colombia, Uruguay, Malta, and Ghana.

It is also possible for authoritarian countries, and not just democracies, to have two-party systems. Competition between two parties has occurred in historical autocratic regimes in countries including Brazil and Venezuela.

In the 1960s Maurice Duverger observed that single-member district single-vote plurality-rule elections tend to produce two-party systems,:217 a phenomenon that became known as Duverger’s law. Whether or not this pattern is true has been heavily debated over the last several decades.

Multi-party systems

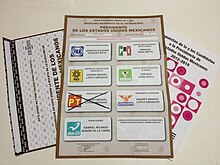

On this 2012 Mexican ballot, voters have more than two parties to choose from.

Multi-party systems are systems in which more than two parties have a realistic chance of holding power and influencing policy. A very large number of systems around the world have had periods of multi-party competition, and two-party democracies may be considered unusual or uncommon compared to multi-party systems. Many of the largest democracies in the world have had long periods of multi-party competition, including India, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Brazil. Multiparty systems encourage characteristically different types of governance than smaller party systems, for example by often encouraging the formation of coalition governments.

The presence of many competing political parties is usually associated with a greater level of democracy, and a country transitioning from having a one-party system to having a many-party system is often considered to be democratizing. Authoritarian countries can include multi-party competition, but typically this occurs when the elections are not fair. For this reason, in two-party democracies like the United States, proponents of forming new competitive political parties often argue that developing a multi-party system would make the country more democratic. However, the question of whether multiparty systems are more democratic than two-party systems, or if they enjoy better policy outcomes, is a subject of substantial disagreement among scholars as well as among the public. In the opposite extreme, a country with a very large number of parties can experience governing coalitions that include highly ideologically diverse parties that are unable to make much policy progress, which may cause the country to be unstable and experience a very large number of elections; examples of systems that have been described as having these problems include periods in the recent history of Israel, Italy, and Finland.

Some multi-party systems may have two parties that are noticeably more competitive than the other parties. Such party systems have been called “two-party-plus” systems, which refers to the two dominant parties, plus other parties that exist but rarely or never hold power in the government. It is also possible for very large multi-party systems, like India’s, to nevertheless be characterized largely by a series of regional contests that realistically have only two competitive parties, but in the aggregate can produce many more than 2 parties that have major roles in the country’s national politics.

Funding

Many of the activities of political parties involve acquiring funds and allocating them in order to achieve political goals. The funding involved can be very substantial, with contemporary elections in the largest democracies typically costing billions or even tens of billions of dollars. Much of this expense is paid by candidates and political parties, which often develop sophisticated fundraising organizations. Because paying for participation in electoral contests is such a central democratic activity, the funding of political parties is an important feature of a country’s politics.

Sources of party funds

Campaign finance restrictions may be motivated by the perception that excessive or secretive contributions to political parties will make them beholden to people other than the voters.

Common sources of party funding across countries include dues-paying party members, advocacy groups and lobbying organizations, corporations, trade unions, and candidates who may self-fund activities. In most countries, the government also provides some level of funding for political parties. Nearly all of the 180 countries examined by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance have some form of public funding for political parties, and about a third of them have regular payments of government funds that goes beyond campaign reimbursements. In some countries public funding for parties depends on the size of that party, for example a country may only provide funding to parties which have more than a certain number of candidates or supporters. A common argument for public funding of political parties is that it creates fairer and more democratic elections by enabling more groups to compete, whereas many advocates for private funding of parties argue that donations to parties are a form of political expression that should be protected in a democracy. Public financing of political parties may decrease parties’ pursuit of funds through corrupt methods, by decreasing their incentive to find alternate sources of funding.

One way of categorizing the sources of party funding is between public funding and private funding. Another dichotomy is between plutocratic and grassroots sources; parties which get much of their funding from large corporations may tend to pursue different policies and use different strategies than parties which are mostly funded through small donations by individual supporters. Private funding for political parties can also be thought of as coming from internal or external sources: this distinguishes between dues from party members or contributions by candidates, and donations from entities outside of the party like non-members, corporations, or trade unions. Internal funding may be preferred because external sources might make the party beholden to an outside entity.

Uses for party funds

There are many ways for political parties to deploy money in order to secure better electoral outcomes. Parties often spend money to train activists, recruit volunteers, create and deploy advertisements, conduct research and support for their leadership in between elections, and promote their policy agenda. Many political parties and candidates engage in a practice called clientelism, in which they distribute material rewards to people in exchange for political support; in many countries this is illegal, though even where it is illegal it may nevertheless be widespread in practice. Some parties engage directly in vote-buying, in which a party gives money to a person in exchange for their vote.

Though it may be crucial for a party to spend more than some threshold to win a given election, there are typically diminishing returns for expenses during a campaign. Once a party has spent more than a certain amount, additional expenditures might not increase their chance of success.

Restrictions

Fundraising and expenditures by political parties are regulated by governments, with regulations largely focusing on who can contribute money to parties, how parties’ money can be spent, and how much of it can pass through the hands of a political party. Two main ways that regulations affect parties is by intervening in their sources of income and by mandating that they maintain some level of transparency about their funding. One common type of restriction on how parties acquire money is to limit who can donate money to political parties; for example, people who are not citizens of a country may not be allowed to make contributions to that country’s political parties, in order to prevent foreign interference. It is also common to limit how much money an individual can give to a political party each election. Similarly, many governments cap the total amount of money that can be spent by each party in an election. Transparency regulations may require parties to disclose detailed financial information to the government, and in many countries transparency laws require those disclosures to be available to the public, as a safeguard against potential corruption.

Creating, implementing, and amending laws regarding party expenses can be extremely difficult, since governments may be controlled by the very parties that these regulations restrict.

Party colours and symbols

Nearly all political parties associate themselves with colours and symbols, primarily to aid voters in identifying, recognizing, and remembering the party. This branding is particularly important in polities where much of the population may be illiterate, so that someone who cannot read a party’s name on a ballot can instead identify that party by colour or logo. Parties of similar ideologies will often use the same colours across different countries. Colour associations are useful as a short-hand for referring to and representing parties in graphical media. They can also be used to refer to coalitions and alliances between political parties and other organizations; examples include purple alliances, red-green alliances, traffic light coalitions, pan-green coalitions, and pan-blue coalitions.

However, associations between colour and ideology are extremely inconsistent: parties of the same ideology in different countries often use different colours, and sometimes competing parties in a country may even adopt the same colours. These associations also have major exceptions. For example, in the United States, red is associated with the more conservative Republican Party while blue is associated with the more liberal Democratic Party, which is different from the typical mapping.

| Ideology | Colours | Symbols | Examples | References |

| Agrarianism | Green |

|

|

:58 |

| Anarchism |

|

|

|

|

| Centrism |

|

|

||

| Communism | Red |

|

|

|

| Conservatism |

|

|

||

| Democratic socialism | Red |

|

|

|

| Fascism |

|

|

|

:56 |

| Feminism |

|

|

|

|

| Green politics | Green |

|

|

|

| Islamism | Green |  |

||

| Liberalism | Yellow |    |

||

| Libertarianism | Yellow | Porcupine |  |

|

| Monarchism |

|

Crown |   |

|

| Pacifism |

|

|

|

|

| Social democracy | Red |

|

|

|

| Socialism | Red | Red rose |  |