Meitnerium is a synthetic chemical element with the symbol Mt and atomic number 109. It is an extremely radioactive synthetic element (an element not found in nature, but can be created in a laboratory). The most stable known isotope, meitnerium-278, has a half-life of 4.5 seconds, although the unconfirmed meitnerium-282 may have a longer half-life of 67 seconds. The GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research near Darmstadt, Germany, first created this element in 1982. It is named after Lise Meitner.

In the periodic table, meitnerium is a d-block transactinide element. It is a member of the 7th period and is placed in the group 9 elements, although no chemical experiments have yet been carried out to confirm that it behaves as the heavier homologue to iridium in group 9 as the seventh member of the 6d series of transition metals. Meitnerium is calculated to have similar properties to its lighter homologues, cobalt, rhodium, and iridium.

Introduction

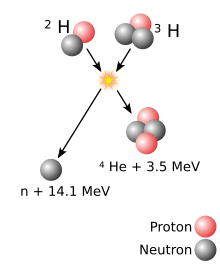

A graphic depiction of a nuclear fusion reaction. Two nuclei fuse into one, emitting a neutron. Reactions that created new elements to this moment were similar, with the only possible difference that several singular neutrons sometimes were released, or none at all.

| External video | |

|---|---|

The heaviest atomic nuclei are created in nuclear reactions that combine two other nuclei of unequal size into one; roughly, the more unequal the two nuclei in terms of mass, the greater the possibility that the two react. The material made of the heavier nuclei is made into a target, which is then bombarded by the beam of lighter nuclei. Two nuclei can only fuse into one if they approach each other closely enough; normally, nuclei (all positively charged) repel each other due to electrostatic repulsion. The strong interaction can overcome this repulsion but only within a very short distance from a nucleus; beam nuclei are thus greatly accelerated in order to make such repulsion insignificant compared to the velocity of the beam nucleus. Coming close alone is not enough for two nuclei to fuse: when two nuclei approach each other, they usually remain together for approximately 10−20 seconds and then part ways (not necessarily in the same composition as before the reaction) rather than form a single nucleus. If fusion does occur, the temporary merger—termed a compound nucleus—is an excited state. To lose its excitation energy and reach a more stable state, a compound nucleus either fissions or ejects one or several neutrons, which carry away the energy. This occurs in approximately 10−16 seconds after the initial collision.

The beam passes through the target and reaches the next chamber, the separator; if a new nucleus is produced, it is carried with this beam. In the separator, the newly produced nucleus is separated from other nuclides (that of the original beam and any other reaction products) and transferred to a surface-barrier detector, which stops the nucleus. The exact location of the upcoming impact on the detector is marked; also marked are its energy and the time of the arrival. The transfer takes about 10−6 seconds; in order to be detected, the nucleus must survive this long. The nucleus is recorded again once its decay is registered, and the location, the energy, and the time of the decay are measured.

Stability of a nucleus is provided by the strong interaction. However, its range is very short; as nuclei become larger, its influence on the outermost nucleons (protons and neutrons) weakens. At the same time, the nucleus is torn apart by electrostatic repulsion between protons, as it has unlimited range. Nuclei of the heaviest elements are thus theoretically predicted and have so far been observed to primarily decay via decay modes that are caused by such repulsion: alpha decay and spontaneous fission; these modes are predominant for nuclei of superheavy elements. Alpha decays are registered by the emitted alpha particles, and the decay products are easy to determine before the actual decay; if such a decay or a series of consecutive decays produces a known nucleus, the original product of a reaction can be determined arithmetically. Spontaneous fission, however, produces various nuclei as products, so the original nuclide cannot be determined from its daughters.

The information available to physicists aiming to synthesize one of the heaviest elements is thus the information collected at the detectors: location, energy, and time of arrival of a particle to the detector, and those of its decay. The physicists analyze this data and seek to conclude that it was indeed caused by a new element and could not have been caused by a different nuclide than the one claimed. Often, provided data is insufficient for a conclusion that a new element was definitely created and there is no other explanation for the observed effects; errors in interpreting data have been made.

History

Meitnerium was named after the physicist Lise Meitner, one of the discoverers of nuclear fission.

Discovery

Meitnerium was first synthesized on August 29, 1982 by a German research team led by Peter Armbruster and Gottfried Münzenberg at the Institute for Heavy Ion Research (Gesellschaft für Schwerionenforschung) in Darmstadt. The team bombarded a target of bismuth-209 with accelerated nuclei of iron-58 and detected a single atom of the isotope meitnerium-266:

- 209

83Bi

+ 58

26Fe

→ 266

109Mt

+

n

This work was confirmed three years later at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research at Dubna (then in the Soviet Union).

Naming

Naming ceremony conducted at the GSI on 7 September 1992 for the namings of elements 107, 108, and 109 as nielsbohrium, hassium, and meitnerium

Using Mendeleev’s nomenclature for unnamed and undiscovered elements, meitnerium should be known as eka-iridium. In 1979, during the Transfermium Wars (but before the synthesis of meitnerium), IUPAC published recommendations according to which the element was to be called unnilennium (with the corresponding symbol of Une), a systematic element name as a placeholder, until the element was discovered (and the discovery then confirmed) and a permanent name was decided on. Although widely used in the chemical community on all levels, from chemistry classrooms to advanced textbooks, the recommendations were mostly ignored among scientists in the field, who either called it “element 109”, with the symbol of E109, (109) or even simply 109, or used the proposed name “meitnerium”.

The naming of meitnerium was discussed in the element naming controversy regarding the names of elements 104 to 109, but meitnerium was the only proposal and thus was never disputed. The name meitnerium (Mt) was suggested by the GSI team in September 1992 in honor of the Austrian physicist Lise Meitner, a co-discoverer of protactinium (with Otto Hahn), and one of the discoverers of nuclear fission. In 1994 the name was recommended by IUPAC, and was officially adopted in 1997. It is thus the only element named specifically after a non-mythological woman (curium being named for both Pierre and Marie Curie).

Isotopes

Meitnerium has no stable or naturally occurring isotopes. Several radioactive isotopes have been synthesized in the laboratory, either by fusing two atoms or by observing the decay of heavier elements. Eight different isotopes of meitnerium have been reported with atomic masses 266, 268, 270, and 274–278, two of which, meitnerium-268 and meitnerium-270, have known but unconfirmed metastable states. A ninth isotope with atomic mass 282 is unconfirmed. Most of these decay predominantly through alpha decay, although some undergo spontaneous fission.

Stability and half-lives

All meitnerium isotopes are extremely unstable and radioactive; in general, heavier isotopes are more stable than the lighter. The most stable known meitnerium isotope, 278Mt, is also the heaviest known; it has a half-life of 4.5 seconds. The unconfirmed 282Mt is even heavier and appears to have a longer half-life of 67 seconds. The isotopes 276Mt and 274Mt have half-lives of 0.45 and 0.44 seconds respectively. The remaining five isotopes have half-lives between 1 and 20 milliseconds.

The isotope 277Mt, created as the final decay product of 293Ts for the first time in 2012, was observed to undergo spontaneous fission with a half-life of 5 milliseconds. Preliminary data analysis considered the possibility of this fission event instead originating from 277Hs, for it also has a half-life of a few milliseconds, and could be populated following undetected electron capture somewhere along the decay chain. This possibility was later deemed very unlikely based on observed decay energies of 281Ds and 281Rg and the short half-life of 277Mt, although there is still some uncertainty of the assignment. Regardless, the rapid fission of 277Mt and 277Hs is strongly suggestive of a region of instability for superheavy nuclei with N = 168–170. The existence of this region, characterized by a decrease in fission barrier height between the deformed shell closure at N = 162 and spherical shell closure at N = 184, is consistent with theoretical models.

| Isotope | Half-life | Decay mode |

Discovery year |

Discovery reaction |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Ref | ||||

| 266Mt | 1.2 ms | α, SF | 1982 | 209Bi(58Fe,n) | |

| 268Mt | 27 ms | α | 1994 | 272Rg(—,α) | |

| 270Mt | 6.3 ms | α | 2004 | 278Nh(—,2α) | |

| 274Mt | 440 ms | α | 2006 | 282Nh(—,2α) | |

| 275Mt | 20 ms | α | 2003 | 287Mc(—,3α) | |

| 276Mt | 450 ms | α | 2003 | 288Mc(—,3α) | |

| 277Mt | 5 ms | SF | 2012 | 293Ts(—,4α) | |

| 278Mt | 4.5 s | α | 2010 | 294Ts(—,4α) | |

| 282Mt | 1.1 min | α | 1998 | 290Fl(e−,νe2α) | |

Predicted properties

Other than nuclear properties, no properties of meitnerium or its compounds have been measured; this is due to its extremely limited and expensive production and the fact that meitnerium and its parents decay very quickly. Properties of meitnerium metal remain unknown and only predictions are available.

Chemical

Meitnerium is the seventh member of the 6d series of transition metals, and should be much like the platinum group metals. Calculations on its ionization potentials and atomic and ionic radii are similar to that of its lighter homologue iridium, thus implying that meitnerium’s basic properties will resemble those of the other group 9 elements, cobalt, rhodium, and iridium.

Prediction of the probable chemical properties of meitnerium has not received much attention recently. Meitnerium is expected to be a noble metal. The standard electrode potential for the Mt3+/Mt couple is expected to be 0.8 V. Based on the most stable oxidation states of the lighter group 9 elements, the most stable oxidation states of meitnerium are predicted to be the +6, +3, and +1 states, with the +3 state being the most stable in aqueous solutions. In comparison, rhodium and iridium show a maximum oxidation state of +6, while the most stable states are +4 and +3 for iridium and +3 for rhodium. The oxidation state +9, represented only by iridium in +, might be possible for its congener meitnerium in the nonafluoride (MtF9) and the + cation, although + is expected to be more stable than these meitnerium compounds. The tetrahalides of meitnerium have also been predicted to have similar stabilities to those of iridium, thus also allowing a stable +4 state. It is further expected that the maximum oxidation states of elements from bohrium (element 107) to darmstadtium (element 110) may be stable in the gas phase but not in aqueous solution.

Physical and atomic

Meitnerium is expected to be a solid under normal conditions and assume a face-centered cubic crystal structure, similarly to its lighter congener iridium. It should be a very heavy metal with a density of around 37.4 g/cm3, which would be the second-highest of any of the 118 known elements, second only to that predicted for its neighbor hassium (41 g/cm3). In comparison, the densest known element that has had its density measured, osmium, has a density of only 22.61 g/cm3. This results from meitnerium’s high atomic weight, the lanthanide and actinide contractions, and relativistic effects, although production of enough meitnerium to measure this quantity would be impractical, and the sample would quickly decay. Meitnerium is also predicted to be paramagnetic.

Theoreticians have predicted the covalent radius of meitnerium to be 6 to 10 pm larger than that of iridium. The atomic radius of meitnerium is expected to be around 128 pm.

Experimental chemistry

Meitnerium is the first element on the periodic table whose chemistry has not yet been investigated. Unambiguous determination of the chemical characteristics of meitnerium has yet to have been established due to the short half-lives of meitnerium isotopes and a limited number of likely volatile compounds that could be studied on a very small scale. One of the few meitnerium compounds that are likely to be sufficiently volatile is meitnerium hexafluoride (MtF

6), as its lighter homologue iridium hexafluoride (IrF

6) is volatile above 60 °C and therefore the analogous compound of meitnerium might also be sufficiently volatile; a volatile octafluoride (MtF

8) might also be possible. For chemical studies to be carried out on a transactinide, at least four atoms must be produced, the half-life of the isotope used must be at least 1 second, and the rate of production must be at least one atom per week. Even though the half-life of 278Mt, the most stable confirmed meitnerium isotope, is 4.5 seconds, long enough to perform chemical studies, another obstacle is the need to increase the rate of production of meitnerium isotopes and allow experiments to carry on for weeks or months so that statistically significant results can be obtained. Separation and detection must be carried out continuously to separate out the meitnerium isotopes and have automated systems experiment on the gas-phase and solution chemistry of meitnerium, as the yields for heavier elements are predicted to be smaller than those for lighter elements; some of the separation techniques used for bohrium and hassium could be reused. However, the experimental chemistry of meitnerium has not received as much attention as that of the heavier elements from copernicium to livermorium.

The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory attempted to synthesize the isotope 271Mt in 2002–2003 for a possible chemical investigation of meitnerium because it was expected that it might be more stable than the isotopes around it as it has 162 neutrons, a magic number for deformed nuclei; its half-life was predicted to be a few seconds, long enough for a chemical investigation. However, no atoms of 271Mt were detected, and this isotope of meitnerium is currently unknown.

An experiment determining the chemical properties of a transactinide would need to compare a compound of that transactinide with analogous compounds of some of its lighter homologues: for example, in the chemical characterization of hassium, hassium tetroxide (HsO4) was compared with the analogous osmium compound, osmium tetroxide (OsO4). In a preliminary step towards determining the chemical properties of meitnerium, the GSI attempted sublimation of the rhodium compounds rhodium(III) oxide (Rh2O3) and rhodium(III) chloride (RhCl3). However, macroscopic amounts of the oxide would not sublimate until 1000 °C and the chloride would not until 780 °C, and then only in the presence of carbon aerosol particles: these temperatures are far too high for such procedures to be used on meitnerium, as most of the current methods used for the investigation of the chemistry of superheavy elements do not work above 500 °C.

Following the 2014 successful synthesis of seaborgium hexacarbonyl, Sg(CO)6, studies were conducted with the stable transition metals of groups 7 through 9, suggesting that carbonyl formation could be extended to further probe the chemistries of the early 6d transition metals from rutherfordium to meitnerium inclusive. Nevertheless, the challenges of low half-lives and difficult production reactions make meitnerium difficult to access for radiochemists, though the isotopes 278Mt and 276Mt are long-lived enough for chemical research and may be produced in the decay chains of 294Ts and 288Mc respectively. 276Mt is likely more suitable, since producing tennessine requires a rare and rather short-lived berkelium target. The isotope 270Mt, observed in the decay chain of 278Nh with a half-life of 0.69 seconds, may also be sufficiently long-lived for chemical investigations, though a direct synthesis route leading to this isotope and more precise measurements of its decay properties would be required.