Food prices refer to the average price level for food across countries, regions and on a global scale. Food prices have an impact on producers and consumers of food.

Example food pricing for tomatoes given in dollars per pound

FAO Food Price Index

Price levels depend on the food production process, including food marketing and food distribution. Fluctuation in food prices is determined by a number of compounding factors. Geopolitical events, global demand, exchange rates, government policy, diseases and crop yield, energy costs, availability of natural resources for agriculture, food speculation, changes in the use of soil and weather events have a direct impact on the increase or decrease of food prices.

The consequences of food price fluctuation are multiple. Increases in food prices endangers food security, particularly for developing countries, and can cause social unrest. Increases in food prices is related to disparities in diet quality and health, particularly among vulnerable populations, such as women and children.

Food prices will on average continue to rise due to a variety of reasons. Growing world population will put more pressure on the supply and demand. Climate change will increase extreme weather events, including droughts, storms and heavy rain, and overall increases in temperature will have an impact on food production.

To a certain extent, adverse price trends can be counteracted by food politics.

An intervention to reduce food loss or waste, if sufficiently large, will affect prices upstream and downstream in the supply chain relative to where the intervention occurred.

Factors

Energy costs

Food production is a very energy-intensive process. Energy is used in the raw materials for fertilizers to powering the facilities needed to process the food. Increases in the price of energy leads to an increase in the price of food. Oil prices also impact on the price of food. Food distribution is also affected by increases in oil prices, leading to increases in the price of food.

Weather events

Adverse weather events such as droughts or heavy rain can cause harvest failure. There is evidence that extreme weather events and natural disasters have an impact on increased food prices.

Global differences

The price of food has risen quite drastically since the 2007–08 world food price crisis, and has been most noticeable in developing countries while less so in the OECD countries and North America.

Consumer prices in the rich countries are massively influenced by the power of discount stores and constitute only a small part of the entire cost of living. In particular, Western pattern diet constituents like those that are processed by fast food chains are comparatively cheap in the Western hemisphere. Profits rely primarily on quantity (see mass production), less than high-price quality. For some product classes like dairy or meat, overproduction has twisted the price relations in a way utterly unknown in underdeveloped countries (“butter mountain”). The situation for poor societies is worsened by certain free trade agreements that allow easier export of food in the “southern” direction than vice versa. A striking example can be found in tomato exports from Italy to Ghana by virtue of the Economic Partnership Agreements where the artificially cheap vegetables play a significant role in the destruction of indigenous agriculture and a corresponding further decline in the already ailing economic power.

Monitoring

FAO has developed an “early warning tool” called the Food Price and Monitoring Analysis (FPMA). After the food crisis of 2008 and 2011, FAO developed an “early warning indicator to detect abnormal growth in prices in consumer markets in the developing world”. The FPMA uses a variety of data sources to feed their database.

Fluctuating food prices have led to some initiative in the industrialized world as well. In Canada, Dalhousie University and the University of Guelph publish Canada’s Food Price Report every year, since 2010. Read by millions of people every year, the report monitors and forecasts food prices for the coming year. The report was created by Canadian researchers Sylvain Charlebois and Francis Tapon.

Measurements

Numbeo

The Numbeo database “allows you to see, share and compare information about food prices worldwide and gives estimation of minimum money needed for food per person per day”.

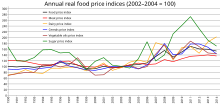

FAO food price index

Food, meat, dairy, cereals, vegetable oil, and sugar price indices, deflated using the World Bank Manufactures Unit Value Index (MUV). The peaks in 2008 and 2011 indicate global food crises

The FAO food price index is a measure of the monthly change in international prices of a market basket of food commodities. It consists of the average of five commodity group price indices, weighted with the average export shares of each of the groups.

- FAO Cereal price index

- FAO Vegetable oil price index

- FAO Dairy price index

- FAO Meat price index

- FAO Sugar Price index

| Year | nominal price idx | deflated price idx |

|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 107.2 | 100.4 |

| 1991 | 105.0 | 98.7 |

| 1992 | 109.2 | 101.1 |

| 1993 | 105.5 | 97.1 |

| 1994 | 110.3 | 101.3 |

| 1995 | 125.3 | 105.3 |

| 1996 | 131.1 | 113.7 |

| 1997 | 120.3 | 111.3 |

| 1998 | 108.6 | 105.6 |

| 1999 | 93.2 | 92.6 |

| 2000 | 91.1 | 92.4 |

| 2001 | 94.6 | 101.0 |

| 2002 | 89.6 | 96.2 |

| 2003 | 97.7 | 98.1 |

| 2004 | 112.7 | 105.0 |

| 2005 | 118.0 | 106.8 |

| 2006 | 127.2 | 112.7 |

| 2007 | 161.4 | 134.6 |

| 2008 | 201.4 | 155.7 |

| 2009 | 160.3 | 132.8 |

| 2010 | 188.0 | 150.7 |

| 2011 | 229.9 | 169.1 |

| 2012 | 213.3 | 158.8 |

| 2013 | 209.8 | 158.5 |

| 2014 | 201.8 | 152.0 |

| 2015 | 164.0 | 123.2 |

| 2016 | 151.6 | 112.3 |

World bank food price watch

The World Bank releases the quarterly Food Price Watch report which highlights trends in domestic food prices in low- and middle-income countries, and outlines the (food) policy implications of food price fluctuations.

Grocery Foods Economics

It is rare for price spikes to hit all major foods in most countries at once, but food prices suffered all-time peaks in 2008 and 2011, posting a 15% and 12% deflated increase year-over-year, representing prices higher than any data collected. One reason for the increase in food prices may be the increase in oil prices at the same time.

It is rare for the spikes to hit all major foods in most countries at once. Food prices rose 4% in the United States in 2007, the highest increase since 1990, and are expected to climb as much again in 2008. As of December 2007, 37 countries faced food crises, and 20 had imposed some sort of food-price controls. In China, the price of pork jumped 58% in 2007. In the 1980s and 1990s, farm subsidies and support programs allowed major grain exporting countries to hold large surpluses which could be tapped during food shortages to keep prices down. However, new trade policies have made agricultural production much more responsive to market demands, putting global food reserves at their lowest since 1983.

Food prices are rising, wealthier Asian consumers are westernizing their diets, and farmers and nations of the third world are struggling to keep up the pace. Asian nations have contributed at a more rapid growth rate in the past five years to the global fluid and powdered milk manufacturing industry. In 2008, this accounted for more than 30% of production with China accounting for more than 10% of both production and consumption in the global fruit and vegetable processing and preserving industry. The trend is similarly evident in industries such as soft drink and bottled water manufacturing, as well as global cocoa, chocolate, and sugar confectionery manufacturing, forecast to grow by 5.7% and 10.0% respectively during 2008 in response to soaring demand in Chinese and Southeast Asian markets.

Rising food prices over recent years have been linked with social unrest around the world, including rioting in Bangladesh and Mexico, and the Arab Spring.

In 2013, Overseas Development Institute researchers showed that rice has more than doubled in price since 2000, rising by 120% in real terms. This was as a result of shifts in trade policy and restocking by major producers. More fundamental drivers of increased prices are the higher costs of fertilizer, diesel and labor. Parts of Asia see rural wages rise with potential large benefits for the 1.3 billion (2008 estimate) of Asia’s poor in reducing the poverty they face. However, this negatively impacts more vulnerable groups who don’t share in the economic boom, especially in Asian and African coastal cities. The researchers said the threat means social-protection policies are needed to guard against price shocks. The research proposed that in the longer run, the rises present opportunities to export for Western African farmers with high potential for rice production to replace imports with domestic production.

Most recently, global food prices have been more stable and relatively low, after a sizable increase in late 2017, they are back under 75% of the nominal value seen during the all-time high in the 2011 food crisis. In the long term, prices are expected to stabilize. Farmers will grow more grain for both fuel and food and eventually bring prices down. This has already occurred with wheat, with more crops planted in the United States, Canada, and Europe in 2009. However, the Food and Agriculture Organization projects that consumers still have to deal with more expensive food until at least 2018.

Impact of climate change in rising food prices

A continuing drought in South Africa may – amongst other factors – have food inflation soar 11% until end of 2016 according to the South African Reserve Bank.