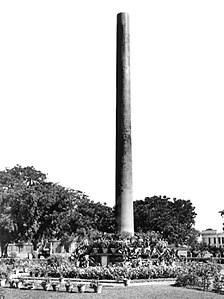

The pillars of Ashoka are a series of monolithic columns dispersed throughout the Indian subcontinent, erected or at least inscribed with edicts by the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka during his reign from c. 268 to 232 BCE. Ashoka used the expression Dhaṃma thaṃbhā (Dharma stambha), i.e. “pillars of the Dharma” to describe his own pillars. These pillars constitute important monuments of the architecture of India, most of them exhibiting the characteristic Mauryan polish. Of the pillars erected by Ashoka, twenty still survive including those with inscriptions of his edicts. Only a few with animal capitals survive of which seven complete specimens are known. Two pillars were relocated by Firuz Shah Tughlaq to Delhi. Several pillars were relocated later by Mughal Empire rulers, the animal capitals being removed. Averaging between 12 and 15 m (40 and 50 ft) in height, and weighing up to 50 tons each, the pillars were dragged, sometimes hundreds of miles, to where they were erected.

The pillars of Ashoka are among the earliest known stone sculptural remains from India. Only another pillar fragment, the Pataliputra capital, is possibly from a slightly earlier date. It is thought that before the 3rd century BCE, wood rather than stone was used as the main material for Indian architectural constructions, and that stone may have been adopted following interaction with the Persians and the Greeks. A graphic representation of the Lion Capital of Ashoka from the column there was adopted as the official Emblem of India in 1950.

All the pillars of Ashoka were built at Buddhist monasteries, many important sites from the life of the Buddha and places of pilgrimage. Some of the columns carry inscriptions addressed to the monks and nuns. Some were erected to commemorate visits by Ashoka. Major pillars are present in the Indian States of Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and some parts of Haryana.

Ashoka and Buddhism

Lion Capital of Ashoka from Sarnath. Ashokan capitals were highly realistic and used a characteristic polished finish, giving a shiny appearance to the stone surface. 3rd century BCE.

Ashoka ascended to the throne in 269 BC inheriting the Mauryan empire founded by his grandfather Chandragupta Maurya. Ashoka was reputedly a tyrant at the outset of his reign. Eight years after his accession he campaigned in Kalinga where in his own words, “a hundred and fifty thousand people were deported, a hundred thousand were killed and as many as that perished…” As he explains in his edicts, after this event Ashoka converted to Buddhism in remorse for the loss of life. Buddhism become a state religion and with Ashoka’s support it spread rapidly. The inscriptions on the pillars set out edicts about morality based on Buddhist tenets. They were added in 3rd centure BCE

Construction

The traditional idea that all were originally quarried at Chunar, just south of Varanasi and taken to their sites, before or after carving, “can no longer be confidently asserted”, and instead it seems that the columns were carved in two types of stone. Some were of the spotted red and white sandstone from the region of Mathura, the others of buff-colored fine grained hard sandstone usually with small black spots quarried in the Chunar near Varanasi. The uniformity of style in the pillar capitals suggests that they were all sculpted by craftsmen from the same region. It would therefore seem that stone was transported from Mathura and Chunar to the various sites where the pillars have been found, and there was cut and carved by craftsmen.

The pillars have four component parts in two pieces: the three sections of the capitals are made in a single piece, often of a different stone to that of the monolithic shaft to which they are attached by a large metal dowel. The shafts are always plain and smooth, circular in cross-section, slightly tapering upwards and always chiselled out of a single piece of stone. There is no distinct base at the bottom of the shaft. The lower parts of the capitals have the shape and appearance of a gently arched bell formed of lotus petals. The abaci are of two types: square and plain and circular and decorated and these are of different proportions. The crowning animals are masterpieces of Mauryan art, shown either seated or standing, always in the round and chiselled as a single piece with the abaci. Presumably all or most of the other columns that now lack them once had capitals and animals. They are also used to commemorate the events of the Buddha’s life.

Currently seven animal sculptures from Ashoka pillars survive. These form “the first important group of Indian stone sculpture”, though it is thought they derive from an existing tradition of wooden columns topped by animal sculptures in copper, none of which have survived. It is also possible that some of the stone pillars predate Ashoka’s reign.

Bottom image: A quite similar frieze from Delphi, 525 BCE.

Origin

Western origin

There has been much discussion of the extent of influence from Achaemenid Persia, where the column capitals supporting the roofs at Persepolis have similarities, and the “rather cold, hieratic style” of the Sarnath Lion Capital of Ashoka especially shows “obvious Achaemenid and Sargonid influence”. India and the Achaemenid Empire had been in close contact since the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley, from circa 500 BCE to 330 BCE.

Hellenistic influence has also been suggested. In particular the abaci of some of the pillars (especially the Rampurva bull, the Sankissa elephant and the Allahabad pillar capital) use bands of motifs, like the bead and reel pattern, the ovolo, the flame palmettes, lotuses, which likely originated from Greek and Near-Eastern arts. Such examples can also be seen in the remains of the Mauryan capital city of Pataliputra.

It has also been suggested that 6th century Greek columns such as the Sphinx of Naxos, a 12.5m Ionic column crowned by a sitted animal in the religious center of Delphi, may have been an inspiration for the pillars of Ashoka. Many similar columns crowned by sphinxes were discovered in ancient Greece, as in Sparta, Athens or Spata, and some were used as funerary steles. The Greek sphinx, a lion with the face of a human female, was considered as having ferocious strength, and was thought of as a guardian, often flanking the entrances to temples or royal tombs.

Indian origin

Some scholars such as John Irwin emphasized a reassessment from popular belief of Persian or Greek origin of Ashokan pillars. He makes the argument that Ashokan pillars represent Dhvaja or standard which Indian soldiers carried with them during battle and it was believed that the destruction of the enemy’s dhvaja brought misfortune to their opponents. A relief of Bharhut stupa railing portrays a queenly personage on horseback carrying a Garudadhvaja. Heliodorus pillar has been called Garudadhvaja, literally Garuda-standard, the pillar dated to 2nd century BC is perhaps the earliest recorded stone pillar which has been declared a dhvaja.

Ashokan edicts themselves state that his words should be carved on any stone slab or pillars available indicating that the tradition of carving stone pillars was present before the period of Ashoka.

Jhon Irwin also highlights the fact that carvings on pillars such as Allahabad pillar was done when it had already been erected indicating its pre Ashokan origins.

Ashoka called his own pillars Silā Thabhe (𑀲𑀺𑀮𑀸𑀣𑀪𑁂, Stone Stambha, i.e. stone pillars). Lumbini inscription, Brahmi script.

Stylistic argument

Though influence from the west is generally accepted, especially the Persian columns of Achaemenid Persia, there are a number of differences between these and the pillars. Persian columns are built in segments whereas Ashokan pillars are monoliths, like some much later Roman columns. Most of the Persian pillars have a fluted shaft while the Mauryan pillars are smooth, and Persian pillars serve as supporting structures whereas Ashokan pillars are individual free-standing monuments. There are also other differences in the decoration. Indian historian Upinder Singh comments on some of the differences and similarities, writing that “If the Ashokan pillars cannot in their entirety be attributed to Persian influence, they must have had an undocumented prehistory within the subcontinent, perhaps a tradition of wooden carving. But the transition from stone to wood was made in one magnificent leap, no doubt spurred by the imperial tastes and ambitions of the Maurya emperors.”

Whatever the cultural and artistic borrowings from the west, the pillars of Ashoka, together with much of Mauryan art and architectural prowesses such as the city of Pataliputra or the Barabar Caves, remain outstanding in their achievements, and often compare favourably with the rest of the world at that time. Commenting on Mauryan sculpture, John Marshall once wrote about the “extraordinary precision and accuracy which characterizes all Mauryan works, and which has never, we venture to say, been surpassed even by the finest workmanship on Athenian buildings”.

Complete list of the pillars

Five of the pillars of Ashoka, two at Rampurva, one each at Vaishali, Lauriya-Araraj and Lauria Nandangarh possibly marked the course of the ancient Royal highway from Pataliputra to the Nepal. Several pillars were relocated by later Mughal Empire rulers, the animal capitals being removed.

The two Chinese medieval pilgrim accounts record sightings of several columns that have now vanished: Faxian records six and Xuanzang fifteen, of which only five at most can be identified with surviving pillars. All surviving pillars, listed with any crowning animal sculptures and the edicts inscribed, are as follows:

Complete standing pillars, or pillars with Ashokan inscriptions

Geographical spread of known pillar capitals.

- Delhi-Topra, Feroz Shah Kotla, Delhi (Pillar Edicts I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII; moved in 1356 CE from Topra Kalan in Yamunanagar district of Haryana to Delhi by Firuz Shah Tughluq.

- Delhi-Meerut, Delhi ridge, Delhi (Pillar Edicts I, II, III, IV, V, VI; moved from Meerut to Delhi by Firuz Shah Tughluq in 1356.

- Nigali Sagar (or Nigliva, Nigalihawa), near Lumbini, Nepal. Pillar missing capital, one Ashoka edict. Erected in the 20th regnal year of Ashoka (c. 249 BCE).

- Rummindei, near Lumbini, Nepal. Also erected in the 20th regnal year of Ashoka (c. 249 BCE), to commemorate Ashoka’s pilgrimage to Lumbini. Capital missing, but was apparently a horse.

- Allahabad pillar, Uttar Pradesh (originally located at Kausambi and probable moved to Allahabad by Jahangir; Pillar Edicts I-VI, Queen’s Edict, Schism Edict).

- Rampurva, Champaran, Bihar. Two columns: a lion with Pillar Edicts I, II, III, IV, V, VI; a bull without inscriptions. The abacus of the bull capital features honeysuckle and palmette designs derived from Greek designs.

- Sanchi, near Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, four lions, Schism Edict.

- Sarnath, near Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, four lions, Pillar Inscription, Schism Edict. This is the famous “Lion Capital of Ashoka” used in the national emblem of India.

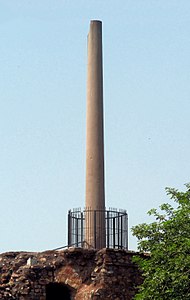

- Lauriya-Nandangarth, Champaran, Bihar, single lion, Pillar Edicts I, II, III, IV, V, VI.

- Lauriya Araraj, Champaran, Bihar (Pillar Edicts I, II, III, IV, V, VI).

- Vaishali, Bihar, single lion, with no inscription.

The Amaravati pillar fragment is rather problematic. It only consists in 6 lines in Brahmi which are hardly decipherable. Only the word vijaya (victory) can be made out, arguably a word also used by Ashoka. Sircar, who provides a detailed study, considers it as probably belonging to an Ashokan pillar.

| Complete standing pillars, or pillars with Ashokan inscriptions | |

|

|

| Complete standing pillars, or pillars with Ashokan inscriptions | |

|

|

Pillars without Ashokan inscriptions

There are also several known fragments of Ashokan pillars, without recovered Ashokan inscriptions, such as the Ashoka pillar in Bodh Gaya, Kausambi, Gotihawa, Prahladpur (now in the Government Sanskrit College, Varanasi), Fatehabad, Bhopal, Sadagarli, Udaigiri-Vidisha, Kushinagar, Arrah (Masarh) Basti, Bhikana Pahari, Bulandi Bagh (Pataliputra), Sandalpu and a few others, as well as a broken pillar in Bhairon (“Lat Bhairo” in Benares) which was destroyed to a stump during riots in 1908. The Chinese monks Fa-Hsien and Hsuantsang also reported pillars in Kushinagar, the Jetavana monastery in Sravasti, Rajagriha and Mahasala, which have not been recovered to this day.

Fragments of Pillars of Ashoka, without Ashokan inscriptions

Kausambi

Gotihawa

Bodh Gaya (originally near Sujata Stupa, brought from Gaya in 1956).

Portion of an Ashokan pillar, found in Pataliputra.

Bhawanipur Rupandehi.

The capitals (Top Piece)

Abacus of the Allahabad pillar of Ashoka, the only remaining portion of the capital of the Allahabad pillar.

There are altogether seven remaining complete capitals, five with lions, one with an elephant and one with a zebu bull. One of them, the four lions of Sarnath, has become the State Emblem of India. The animal capitals are composed of a lotiform base, with an abacus decorated with floral, symbolic or animal designs, topped by the realistic depiction of an animal, thought to each represent a traditional directions in India.

The horse motif on the Sarnath Lion Capital of Ashoka, is often described as an example of Hellenistic realism.

Various foreign influences have been described in the design of these capitals. The animal on top of a lotiform capital reminds of Achaemenid column shapes. The abacus also often seems to display some influence of Greek art: in the case of the Rampurva bull or the Sankassa elephant, it is composed of honeysuckles alternated with stylized palmettes and small rosettes. A similar kind of design can be seen in the frieze of the lost capital of the Allahabad pillar. These designs likely originated in Greek and Near-Eastern arts. They would probably have come from the neighboring Seleucid Empire, and specifically from a Hellenistic city such as Ai-Khanoum, located at the doorstep of India. Most of these designs and motifs can also be seen in the Pataliputra capital. The Diamond throne of Bodh Gaya is another example of Ashokan architecture circa 260 BCE, and displays a band of carvings with palmettes and geese, similar to those found on several of the Pillars of Ashoka.

Chronological order

Based on stylistic and technical analysis, it is possible to establish a tentative chronological orders for the pillars. The earliest one seems to be the Vaishali pillar, with its stout and short column, the rigid lion and the undecorated square abacus. Next would follow the Sankissa elephant and the Rampurva bull, also not yet benefiting from Mauryan polish, and using a Hellenistic abacus of lotus and palmettes for decoration. The abacus would then adopt the Hamsa goose as an animal decorative symbol, in Lauria Nandangarh and the Rampurva lion. Sanchi and Sarnath would mark the culmination with four animals back-to-back instead of just one, and a new and sophisticated animal and symbolic abacus (the elephant, the bull, the lion, the horse alternating with the Dharma wheel) for the Sarnath lion. Other chronological orders have also been proposed, for example based on the style of the Ashokan inscriptions on the pillars, since the stylistically most sophisticated pillars actually have the engravings of the Edicts of Ashoka of the worst quality (namely, very poorly engraved Schism Edicts on the Sanchi and Sarnath pillars, their only inscriptions). This approach offers an almost reverse chronological order to the preceding one. According to Irwin, the Sankissa elephant and Rampurva bull pillars with their Hellenistic abacus are pre-Ashokan. Ashoka would then have commissioned the Sarnath pillar with its famous Lion Capital of Ashoka to be built under the tutelage of craftsmen from the former Achaemenid Empire, trained in Perso-Hellenistic statuary, whereas the Brahmi engraving on the very same pillar (and on pillars of the same period such as Sanchi and Kosambi-Allahabad) was made by inexperienced Indian engravers at a time when stone engraving was still new in India. After Ashoka sent back the foreign artists, style degraded over a short period of time, down to the time when the Major Pillar Edicts were engraved at the end of Ashoka’s reign, which now displayed very good inscriptional craftsmanship but a much more solemn and less elegant style for the associated lion capitals, as for the Lauria Nandangarh lion and the Rampurva lion.

Known capitals of the pillars of Ashoka Ordered chronologically based on stylistic and technical analysis.

Vaishali lion

Sankissa elephant.

Rampurva zebu bull original (now in Rashtrapati Bhavan, New Delhi).

Lauria Nandangarh lion.

Rampurva lion.

Four lions, once possibly crowned by a wheel, from Sanchi.

The “Lion Capital of Ashoka”, from Sarnath.

Of the Allahabad pillar, only the abacus remains, the bottom bulb and the crowning animal having been lost. The remains are now located in the Allahabad Museum.

The elephant-crowned pillar of Ashoka at the Mahabodhi Temple, Gaya. Bharhut relief, 100 BCE.

A few more possibly Ashokan capitals were also found without their pillars:

Kesariya (capital). Only the capital was found in the Kesaria stupa. It was discovered by Markham Kittoe in 1862, and said to be similar to the lion of the Lauriya Nandangarh pillar, except for the hind legs of the lion, which did not protrude beyond the abacus. This capital is now lost.

Udaigiri-Vidisha (capital only at the Udayagiri Caves, visible here). Attribution to Ashoka however is disputed (ranging from the 2nd century BCE Sunga period, to the Gupta period.).

It is also known from various ancient sculptures (reliefs from Bharhut, 100 BCE), and later narrative account by Chinese pilgrims (5-6th century CE), that there was a pillar of Ashoka at the Mahabodhi Temple founded by Ashoka, that it was crowned by an elephant. The same Chinese pilgrims have reported that the capital of the Lumbini pillar was a horse (now lost), which, by their time had already fallen to the ground.

Inscriptions

Main article: Edicts of Ashoka

Ashoka also called his pillars “Dhaṃma thaṃbhā” (𑀥𑀁𑀫𑀣𑀁𑀪𑀸, Dharma stambha), i.e. “pillars of the Dharma”. 7th Major Pillar Edict. Brahmi script.

The inscriptions on the columns include a fairly standard text. The inscriptions on the columns join other, more numerous, Ashokan inscriptions on natural rock faces to form the body of texts known as the Edicts of Ashoka. These inscriptions were dispersed throughout the areas of modern-day Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Afghanistan and Pakistan and represent the first tangible evidence of Buddhism. The edicts describe in detail Ashoka’s policy of Dhamma, an earnest attempt to solve some of problems that a complex society faced. In these inscriptions, Ashoka refers to himself as “Beloved servant of the Gods” (Devanampiyadasi). The inscriptions revolve around a few recurring themes: Ashoka’s conversion to Buddhism, the description of his efforts to spread Buddhism, his moral and religious precepts, and his social and animal welfare program. The edicts were based on Ashoka’s ideas on administration and behaviour of people towards one another and religion. Alexander Cunningham, one of the first to study the inscriptions on the pillars, remarks that they are written in eastern, middle and western Prakrits which he calls “the Punjabi or north-western dialect, the Ujjeni or middle dialect, and the Magadhi or eastern dialect.” They are written in the Brahmi script.

Minor Pillar Edicts

Main article: Minor Pillar Edicts

These contain inscriptions recording their dedication, as well as the Schism Edicts and the Queen’s Edict. They were inscribed around the 13th year of Ashoka’s reign.

Sanchi pillar (Schism Edict)

Sarnath pillar (Schism Edict)

Allahabad pillar (Schism Edict, Queen Edict, and also Major Pillar Edicts)

Lumbini (Rummindei), Nepal (the upper part broke off when struck by lightning; the original horse capital mentioned by Xuanzang is missing) was erected by Ashoka where Buddha was born.

Nigali Sagar (or Nigliva), near Lumbini, Rupandehi district, Nepal (originally near the Buddha Konakarnana stupa)

Kosambi-Allahabad Schism Edict.

Sanchi Schism Edict.

Sarnath Schism Edit.

Rummindei, in Lumbini.

Nigali Sagar.

Major Pillar Edicts

Fragment of the 6th Major Pillar Edict, from the Delhi-Meerut Pillar of Ashoka, British Museum.

Main article: Major Pillar Edicts

Asoka’s 6 Major Pillar Edicts have been found at Kausambhi (Allahabad), Topra (now Delhi), Meerut (now Delhi), Lauriya-Araraj, Lauriya-Nandangarh, Rampurva (Champaran), and a 7th one on the Delhi-Topra pillar. These pillar edicts include:

I Asoka’s principle of protection to people

II Defines dhamma as minimum of sins, many virtues, compassion, liberality, truthfulness and purity

III Abolishes sins of harshness, cruelty, anger, pride etc.

IV Deals with duties of government officials

V List of animals and birds which should not be killed on some days and another list of animals which cannot be killed on any occasion. Describes release of 25 prisoners by Asoka.

VI Works done by Asoka for Dhamma Policy. He says that all sects desire both self-control and purity of mind.

VII Testimental edict.

Major Pillar Edicts I, II, III (Delhi-Topra)

Major Pillar Edicts IV (Delhi-Topra)

Major Pillar Edicts V-VII (Delhi-Topra)

Major Pillar Edicts VII, second part (Delhi-Topra)

Description of the pillars

Front view of the single lion capital in Vaishali.

Pillars retaining their animals

Main article: Lion Capital of Ashoka

1941165,204+0.90%1951167,713+0.15%1961190,436+1.28%1971227,902+1.81%1981268,366+1.65%1991317,622+1.70%2001373,372+1.63%2011441,162+1.68%source:

According to the 2011 census Boudh district has a population of 441,162, roughly equal to the nation of Malta. This gives it a ranking of 552nd in India (out of a total of 640). The district has a population density of 142 inhabitants per square kilometre (370/sq mi) . Its population growth rate over the decade 2001-2011 was 17.82%. Baudh has a sex ratio of 991 females for every 1000 males, and a literacy rate of 72.51%.

At the time of the 2011 Census of India, 78.69% of the population in the district spoke Odia and 20.55% Sambalpuri as their first language.

Languages of Boudh district in 2011 census

Culture

Boudh is a new district but the civilization of Boudh area is as old as the oldest river valley civilizations of the world. As all civilization started on the banks of the river and the riverine passage was the mode of transport in the days of yore, people of Boudh claimed to be inheritors of rich culture. From 2nd century AD up to a period of one thousand years, Boudh was an important seat of Jagannathism , i.e Odia Vaishnavism, Shaivism and Shakti cult in the country. Boudh is part of Odia Culture. It was highly developed educationally and culturally during the Soma Vanshi period and also during the Gangas and Surya Vanshi period.

Communal dance

Various types of dances are prevalent in the district. These are usually held during socio-religious functions. An account of some of the major dances is given below.

Karma dance

The Karma dance of Boudh is quite different from the Karama dance of the Oraons of Sundergarh District. In Boudh, the Ghasis perform this festival and dance. They observe Sana Karama festival on the 11th day of the dark fortnight in the month of Bhadrab (August–September) and Karama festival on the 11th day of the bright fortnight of the same month. On both the occasions, males and females belonging to the Ghasi community perform the Karama dance. The girls sing Karama songs and the boy play on the Mrudunga and Madala. They generally sing songs relating to goddess Karama whom they worship on the occasion.

Danda Nata

Danda Nata

Danda Nata is a ritual dance and is very popular in Boudh. The participants of the dance are the devotees of the god Hara and goddess Parvati. They perform the dance in the month of Chaitra (March–April) and Vaishakha (April–May).

Dalkhai dance

The people of Boudh perform this dance during the month of Aswina (September–October) on the occasion of Bhaijuntia (Bhatri Dwitya) In this dance young girls stand in a line or in a semi-circular pattern with songs known as Dalkhai songs.

Fairs and festivals

The Hindus of the district observe a number of festivals all year round. These festivals may broadly be divided into two categories, viz. domestic festivals observed in each household and public festivals and fairs where people congregate in large numbers on some auspicious days. The domestic festivals are confined to worship of family deities, observance of Ekadashi, various vratas, etc. most of them being guided by phases of the moon. The public festivals are usually religious ceremonies attended by a large number of men, women, and children who come for worship as well as entertainment. An account of some of the important festivals in the district is given below.

Chuda Khai Jatra

This function is observed in the last Friday of Margasira (November–December) wherein both males and females gather in a place and scold each other in filthy languages and also fight each other. The concept behind this is that by such function the land will yield good crops.

Ratha Jatra

The Ratha Jatra or Car Festival of Lord Jagannath is held on the 2nd day of the bright fortnight in the month of Asadha (June–July). The festival is observed at different places of Boudh, but the festival observed in the Boudh town deserves special mention. During this festivals, people of this district wear new dresses and make delicious food. Thousands of people from nearby villages of the district congregate at Boudh for this occasion. The Raja of Boudh performs the ritual as in case of Ratha Jatra of Puri. The three deities – Lord Jagannath, Balabhadra, and Subhadra are taken in a car from the main temple to the Mausima temple. The deities stay there for 7 days. During this time different types melas, mina bazaar are organized at Boudh as large numbers of people come to Boudh.

Laxmi Puja

Laxmi Puja is observed in almost all Hindu households on every Thursday in the month of Margasira (November–December). The Hindu women celebrate this festival with great austerity and devotion. On the Thursdays, the house and the courtyard are decorated with chita or alpana designs, and Laxmi, the goddess of wealth and prosperity, is evoked and worshipped. The last Thursday of the month marks the end of the Puja when rice cakes and other preparations of sweets are offered to the goddess.

Nuakhai

Nuakhai is an agricultural festival. It is observed more or less in all parts of the district. This ceremony generally takes place in the bright fortnight of Bhadraba (August–September) on an auspicious day fixed by the astrologer. On this occasion, preparations of new rice are offered to gods, goddesses, and ancestors, after which members of the family along with friends and relatives partake of the new rice. The head of the family officiates in this function.

Sivaratri

Sivaratri festival is observed in all Siva temples on the 14th day of the dark fortnight in the month of Phalguna (February–March). The devotees remain awake throughout the night and worship Lord Siva. At midnight a lamp called Mahadipa is taken to the top of the temple and is kept burning throughout the night. The devotees break their fast after seeing the Mahadipa. This festival is observed with great pomp and splendor in the Siva temple of Boudh town namely Matengeswar, Chandrachuda, Mallisahi, and at Charisambhu (Jagati), Karadi, Sarsara, Dapala, Bhejigora, and Raniganj.

Dasahara

Vijayadashami (Dasahara)

The Durga Puja and Dasahara festivals are celebrated during the bright fortnight in the month of Aswina (September–October). Generally, this Puja continues for 4 days from Saptami up to Dasami. The images of goddess Durga are worshipped in a few places in the district of which celebrations held at Boudh town and at Sakta shrine of Purunakatak deserve special mention.

Dasahara has a special significance to the warrior caste. They worship their old weapons of war and exhibit physical feats on the occasion. Their heroic forebears used to start on fresh military expeditions during this season of the year.

Dola Jatra

Dola Jatra is usually celebrated from the day of Phagu Dasami to Phagu Purnima. In some places, it is observed from the next day of Phagu Purnima to Chaitra Krishna Panchami. On this occasion, the images of Radha and Krishna are placed in a decorated biman and carried in procession to the accompaniment of music. At places, the bimans carrying Radha-Krishna images from different places assemble together for a community worship. This assembly of the gods called melan is usually celebrated with great pomp and show. This is the main festival of the people belonging to the Gaura caste. They worship the cow and play naudi (a play with sticks) by singing songs relating to Radha and Krishna.

Puajiuntia and Bhaijiuntia

The Puajintuia ceremony is celebrated on the 8th day of the dark fortnight in the month of Aswina (September–October). On this occasion almost all the mothers worship the deity Dutibahana for long life and prosperity of their sons.

On the 8th day of the bright fortnight of Aswina (September–October), Bhaijiuntia is observed. The sisters worship goddess Durga on this occasion for the long and happy life of their brothers.

Ramaleela

Ramanavami or Ramaleela celebration is celebrated during the month of Chaitra. It is observed for 8 to 30 days at different temples of Rama. It is a dance drama in open theatre for the entertainment of people during which seven parts of the epic Ramayana is being played by different artists on different nights. It is observed with great pomp and shows in Raghunath temple at Boudh town for 18 days. It is also famously observed at Laxmiprasad village of Boudh town. It is also observed with religious fervor at Raghunath Jew temple of Debgarh and in the village Bahira.

Kailashi Jatra

Kailashi or Kalashi Jatra is observed on the 11th day of bright fortnight of Kartika which is also an auspicious month for Hindu. It is observed in the kalashi kothi (worshipping place). The walls of the kalashi kothi is painted with different god and goddess. A special type of musical instrument called Dhunkel is being played during this occasion inside the worshipping place. Girasinga is famous for this festival in the district. It is also observed in Palas, Landibandha, Gandhinagar Khuntbandha, Chandrapur, gundulia, Sarsara, Samapaju, Sidhapur, Khaligaon, Ramgad and Khaliabagicha of Boudh town.

Christian festivals

The Christians of the district observe New Year’s Day, Good Friday, Easter Saturday, Easter Sunday, Easter Monday, Christmas Eve and Christmas Day with great pomp and show.

Muslim festivals

The Muslim inhabitants celebrate Id-Ul-Fitre, Id-Ul-Zuha, Shab-E-Barat, Shab-E-Quadar, Juma-Tul-Wida, Muharram, Shab-E-Meraj, Milad-Un-Nabi, and Ramzan like their fellow brethren in other parts of the state.

Recreation

Leisure and recreation are essential for life. People usually gather in the evening at the temple or in a common place where the priest or Puran panda recites and explains from the religious texts like the Bhagabat, the Mahabharat, the Ramayan, the Haribansa, or other Puranas. The singing of Bhajan or kirtan accompanied with musical instruments like khanjani, gini, mrudanga or harmonium is also another popular form of entertainment for the people. Occasionally acrobatic feats, monkey dance, beard dance, and snake charming and magic performed by itinerant professional groups also provide entertainment to the people. In urban areas cinema, opera are a common source of entertainment. Besides this recreational clubs are also functioning in the district.

Tourism

Boudh is known for its century-old temples, ancient Buddha statues, and caves. With the spread of Saivism, Vaishnavism and a number of other cults, numerous shrines dedicated to various deities were found in this region.

Buddha Statues

Three remarkable Buddhist statues are found in Boudh are indicative of the fact that it was once a center of Buddhist culture. One of the statues is present in Boudh town. The total height of this image is 6 ft. 9 inches of which the seated figure measures 4 ft. 3 inches in height and 3 ft. 10 inches from knee to knee. It is seated in the bhumisparsa mudra on a lotus throne 1 ft. 2 inches in height placed on a pedestal 11 inches in height and 4 ft. 6 inches in breadth. The whole image is built up in sections with carved stones. The only attendant figures are two Gandharvas flying with garlands in their hands on the sides of the head. On the whole, this colossus of Boudh compares favourably with similar colossi at Udayagiri and Lalitgiri in Cuttack district. The image is uninscribed and beneath the pedestal is the ancient stone pavement of the original shrine. This appears to be the site of an ancient Buddhist monastery the remains of which are still to be found.

At a distance of 40 km. from Boudh town the image of Buddha is in the village shyamsundarpur. The height of the statue is 5 ft. and the image is in the same posture as in Boudh town. Here also the only attendant figures are two Gandharvas flying with garlands in their hands at the back of the Budhha statue. The image is built up of sandstone. Locally it is known as Jharabaudia Mahaprabhu.

Another Budhha statue is also seen in the village Pragalapur, which is 2 km from Shyamsundarpur. The height of this statue is 3.5 ft. In the left-hand side of the statue there are three numbers of the invisible image and on the right-hand side, their lies five numbers of an image called ugratara.

Ramanath Temple

Rameshwar – Ramnath Temples

A group of three temples of Siva at Boudh town are called the Rameswar or Ramanath temples, dating back to the 9th century AD are reputed for their special feature. The decorative motifs and the plastic art of three temples at Boudh are certainly superior to and older than the great Lingaraj and Ananta Vasudeva group. One particular feature of the Ramanath temple is worth particular attention. Their plan is quite different from any other temples. In plan, these temples are eight-rayed stars and the argha-pattas of the lingas are also similar. These magnificent temples built of red sandstone and profusely carved are stated to have been constructed in the mid-9th century AD. The temples with rich texture and curved surfaces are noteworthy. Each of these temples stands by itself on a raised platform, and consists of a cell and an attached portico. The minute recesses and angularities produce a charming effect of light and shade and confer an appearance of greater height from the continued cluster of vertical lines than they really possess. Archaeological Survey of India has preserved this temple.

Jogindra Villa Palace

This is the palace of ex-Ruler of Boudh locally known as Raja batis. This was constructed during the reign of Raja Jogindra Dev, who was a benevolent and generous ruler. The palace is a picturesque and handsome building commanding a fine view of Mahanadi.

Hanuman Temple

This temple is situated in the midst of the river Mahandai to the east of Boudh town. The Hanuman temple was constructed by a religious mendicant. This shrine was constructed on a large stone. The temple commands an extensive view, especially during rain when the Mahanadi is in full bloom.

Chandra Chuda and Matengeswar Temple

The Chandra Chuda and Matengeswar temple are situated on the bank of river Mahanadi in Boudh town. Both the temples are Shiva temples. In the Matengeswar temple, there is also a separate temple for goddess Parvati.

Madan Mohan Temple

In Madan Mohan temples idol of Radha-Krishna has been worshipped. One Gayatri Pragnya Mandir is also situated at the adjacent to these temples.

Jagannath Temple

This temple is one of the ancient temples of Odisha. It is situated in the heart of Boudh town.

Debagarh

The Raghunath temple at Debagarh is 14 km from Boudh town. The marble statue of Rama, Laxman, Sita and Hanuman are being worshipped here. There is also a pond here.

Chari Sambhu Temple

Chari Sambhu Temple

The Chari sambhu temple was previously named as Gandharadi temple. It is situated near the village Jagati at a distance of 16 km. from Boudh. It is the renowned twin temples of Nilamadhava and Sidheswar. These temples were constructed under the patronage of the Bhanja rulers of Khinjali mandala in the 9th century AD. These two temples were built on one platform which is exactly similar to each other. The one on the left hand is dedicated to Siva named Siddheswar and its shikhara is surmounted by a Sivalinga. The second is dedicated to Vishnu, named Nilamadhava and its shikhara is surmounted by a wheel of blue chlorite. The principle of construction of the jagamohans at Gandhara is slightly different from that of other temples. Their roofs are built on the cantilever principle and originally it appears to have been supported on twelve large pillars arranged as a hollow square.

Thus each side had four pillars of which the central ones flanked an opening. Originally these two jagamohanas appear to have been open on all sides; but later on, the lintels on all sides appear to have given away and then it became necessary to fill in the gaps between pillars with the exception of the four openings with ashlar masonry. At the same time, the side openings were filled up with a jali or lattice of blue chlorite towards the bottom and a frieze of four miniature temple shikhara over it. This arrangement is not followed in later temples where the ingress of light into jagamohana is through four or five stone pillars in the opening used as window bars.

The style of ornamentation in the jagamohans of the Gandharadi temples is altogether different. Even stylized chaitya-windows are rarely to be seen at Gandharadi except at the bases of the pilasters of the vimana. the ornamentation on these two jagamohans is very simple and much less overcrowded. The importance of the Gandharadi temples lies in the fact that they provide a link and that a very important one, in the chain of the evolution, in the chain of the evolution of the medieval Orissa temple type.

The Gandharadi temple is also locally known as ‘Chari Sambhu Mandira‘ (the temple of four Sambhus or Siva lingas). In the Siva temple Siddheswar is the presiding deity. In the Jagamohan, to the left of the door leading to the sanctum is the siva Linga called Jogeswar and to the right of the door is the linga called Kapileswar. At a little distance from Siddheswar stands the temples of Paschima Somanath (Siva), the door of the temple opening to the west.

Some images of considerable antiquity are found worshipped in shrines nearby. Notable among them are the images of Ganesh in the temple of Paschima Somanath and an image of eight armed Durga worshipped under a banyan tree, the later image being badly eroded due to the vagaries of weather. These images probably once adorned the Siddheswar temple. Portions of carved doorsteps in black chlorite and other decorative motifs have been unearthed. In the vicinity of the temple. Five feet (1.52 meters) high Hanuman image of good workmanship is being worshipped near the village Jagati and a carved Nabagraha slab is lying in the cornfield. Archaeological Survey of India has preserved this place.

Purunakatak

Bhairabi Temple, Purunakatak

Purunakatak, 30 km from Boudh on Boudh-Bhubaneswar road, is a trading center of some importance. Goddess Bhairabi is the presiding deity of Boudh District. Durga puja festival is observed here for 16 days. Just opposite to the Bhairabi temple is the temple of Maheswar Mahadev. One Inspection Bungalow is nearby for staying.

Places of Interest

- Padmatola Sanctuary

- Dambarugada Mountains

- Nayakpada Cave (Patali Shrikhetra)

- Marjakud Island

Apart from the above places, there are numerous places in Boudh for tourist visits e.g. Asurgada, Shiva temple at Karadi, Sarsara and Baunsuni, Jatasamadhi temple at Balasinga (Temple of Mahima Cult), and Paljhir Dam.

Legislation

Vidhan Sabha Constituencies

The following are the 2 Vidhan sabha constituencies of Boudh district and the elected members of that area.

| No. | Constituency | Reservation | Extent of the Assembly Constituency (blocks) | Member of 15th Assembly | Party |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 85 | Kantamal | None | Kantamal, Boudh (part) | Mahidhar Rana | BJD |

| 86 | Boudh | None | Harbhanga, Boudhgarh (NAC), Boudh (part) | Pradip Kumar Amat | BJD |

Star Wars92% (130 reviews)90 (24 reviews)N/AThe Empire Strikes Back94% (102 reviews)82 (25 reviews)N/AReturn of the Jedi82% (94 reviews)58 (24 reviews)N/AStar Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace52% (232 reviews)51 (36 reviews)A−Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones65% (253 reviews)54 (39 reviews)A−Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith80% (299 reviews)68 (40 reviews)A−Star Wars: The Force Awakens92% (437 reviews)80 (55 reviews)AStar Wars: The Last Jedi90% (472 reviews)84 (56 reviews)AStar Wars: The Rise of Skywalker51% (495 reviews)54 (61 reviews)B+Spin-off filmsStar Wars: The Clone Wars18% (171 reviews)35 (30 reviews)B−Rogue One: A Star Wars Story84% (446 reviews)65 (51 reviews)ASolo: A Star Wars Story69% (475 reviews)62 (54 reviews)A−Television filmsStar Wars Holiday Special27% (15 reviews)N/AN/AThe Ewok Adventure21% (14 reviews)N/AN/AEwoks: The Battle for Endor33% (3 reviews)N/AN/A

Accolades

Academy Awards

The eleven live-action films together have been nominated for 37 Academy Awards, of which they have won seven. The films were also awarded a total of three Special Achievement Awards. The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi received Special Achievement Awards for their visual effects, and Star Wars received a Special Achievement Award for its alien, creature and robot voices.

| Film | Best Picture | Best Director | Best Supporting Actor | Best Original Screenplay | Best Costume Design | Best Film Editing | Best Makeup | Best Original Score | Best Production Design | Best Sound Editing | Best Sound Mixing | Best Visual Effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Star Wars | Nominated | Nominated | Nominated | Won | category not yet introduced | Won | Won | Won | |||||

| The Empire Strikes Back | Nominated | Special Achievement | |||||||||||

| Return of the Jedi | Nominated | ||||||||||||

| The Phantom Menace | Nominated | ||||||||||||

| Attack of the Clones | |||||||||||||

| Revenge of the Sith | Nominated | ||||||||||||

| The Force Awakens | Nominated | Nominated | Nominated | Nominated | |||||||||

| Rogue One | |||||||||||||

| The Last Jedi | Nominated | Nominated | |||||||||||

| Solo | Nominated | ||||||||||||

| The Rise of Skywalker | Nominated | Nominated | Nominated | ||||||||||

Grammy Awards

The franchise has received a total of fifteen Grammy Award nominations, winning six.

| Film | Album of the Year | Best Pop Instrumental Performance | Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media | Best Instrumental Composition | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Star Wars | Nominated | Won | Won | Won | |

| The Empire Strikes Back | Nominated | Won | Won | ||

| Return of the Jedi | Nominated | ||||

| The Phantom Menace | Nominated | ||||

| Revenge of the Sith | Nominated | Nominated | |||

| The Force Awakens | Won | ||||

| Solo | Nominated |

- Notes

- ^ Alec Guinness for his performance as Obi-Wan Kenobi.

- ^ For “Star Wars – Main Title”

- ^ For “Yoda’s Theme”

- ^ For The Empire Strikes Back. Also nominated for “The Imperial March (Darth Vader’s Theme) and “Yoda’s Theme”.

- ^ For “Anakin’s Betrayal”

Library of Congress

In 1989, the Library of Congress selected the original Star Wars film for preservation in the U.S. National Film Registry, as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” The Empire Strikes Back was selected in 2010. 35mm reels of the 1997 Special Editions were the versions initially presented for preservation because of the difficulty of transferring from the original prints, but it was later revealed that the Library possessed a copyright deposit print of the original theatrical releases. By 2015, Star Wars had been transferred to a 2K scan which can be viewed by appointment.

Emmy Awards

Caravan of Courage: An Ewok Adventure was one of four films to be juried-awarded Emmys for Outstanding Special Visual Effects at the 37th Primetime Emmy Awards. The film was additionally nominated for Outstanding Children’s Program but lost in this category to an episode of American Playhouse.

At the 38th Primetime Emmy Awards, Ewoks: The Battle for Endor and the CBS documentary Dinosaur! were both juried-awarded Emmys for Outstanding Special Visual Effects. The film additionally received two nominations for Outstanding Children’s Program and Outstanding Sound Mixing for a Miniseries or a Special.

Unproduced and rumored films

In early 2013, Bob Iger announced the development of a spin-off film written by Simon Kinberg, reported by Entertainment Weekly to focus on bounty hunter Boba Fett during the original trilogy. In mid-2014, Josh Trank was officially announced as the director of an undisclosed spin-off film, but had left the project a year later due to creative differences, causing a teaser for the film to be scrapped from Star Wars Celebration. In May 2018, it was reported that James Mangold had signed on to write and direct a Fett film, with Kinberg attached as producer and co-writer. By October, the Fett film was reportedly no longer in production, with the studio instead focusing on The Mandalorian, which utilizes a similar character design.

In August 2017, it was rumored that films focused on Jabba the Hutt, and Jedi Masters Obi-Wan and Yoda were being considered or were in development. Stephen Daldry was reportedly in early negotiations to co-write and direct the Obi-Wan movie. At D23 Expo in August 2019, it was announced that a streaming series about the character would be produced instead.

Felicity Jones, who played Jyn Erso in Rogue One, has the option of another Star Wars film in her contract; notwithstanding her character’s fate in Rogue One, it has been speculated that she could return in other anthology films. In 2018, critics noted that Solo was intentionally left open for sequels. Alden Ehrenreich and Emilia Clarke confirmed that their contracts to play Han Solo and Q’ira extended for additional films, if required.

An unannounced film centered around the Mos Eisley Spaceport was reportedly put on hold or cancelled in mid-2018, leading to rumors of the cancellation or postponement of the anthology series. Lucasfilm swiftly denied the rumors as “inaccurate”, confirming that multiple unannounced films were in development.

Game of Thrones creators David Benioff and D. B. Weiss were to write and produce a trilogy of Star Wars films scheduled to be released in December 2022, 2024, and 2026, which were first announced to be in development in February 2018. However, citing their commitment to a Netflix deal, the duo stepped away from the project in October 2019. Kennedy stated her openness to their returning when their schedules allow.

Additionally, though unconfirmed by Lucasfilm, BuzzFeed reported in May 2019 that Laeta Kalogridis was writing the script for the first film in a potential Knights of the Old Republic trilogy. In January 2020, a film set in the era of The High Republic was rumored to be in development.