Bartolomeo Cristofori di Francesco Italian pronunciation: ; May 4, 1655 – January 27, 1731 was an Italian maker of musical instruments famous for inventing the piano.

Life

The available source materials on Cristofori’s life include his birth and death records, two wills, the bills he submitted to his employers, and a single interview carried out by Scipione Maffei. From the latter, both Maffei’s notes and the published journal article are preserved.

Cristofori was born in Padua in the Republic of Venice. Nothing is known of his early life. A tale is told that he served as an apprentice to the great violin maker Nicolò Amati, based on the appearance in a 1680 census record of a “Christofaro Bartolomei” living in Amati’s house in Cremona. However, as Stewart Pollens points out, this person cannot be Bartolomeo Cristofori, since the census records an age of 13, whereas Cristofori according to his baptismal record would have been 25 at the time. Pollens also gives strong reasons to doubt the authenticity of the cello and double bass instruments sometimes attributed to Cristofori.

Probably the most important event in Cristofori’s life is the first one of which we have any record: in 1688, at age 33, he was recruited to work for Prince Ferdinando de Medici. Ferdinando, a lover and patron of music, was the son and heir of Cosimo III, Grand Duke of Tuscany. Tuscany was at the time still a small independent state.

It is not known what led Ferdinando to recruit Cristofori. The Prince traveled to Venice in 1688 to attend the Carnival, so he may have met Cristofori passing through Padua on his way home. Ferdinando was looking for a new technician to take care of his many musical instruments, the previous incumbent having just died. However, it seems possible that the Prince wanted to hire Cristofori not just as his technician, but specifically as an innovator in musical instruments. It would be surprising if Cristofori at age 33 had not already shown the inventiveness for which he later became famous.

The evidence—all circumstantial—that Cristofori may have been hired as an inventor is as follows. According to Stewart Pollens, there were already several qualified individuals in Florence who could have filled the position; however, the Prince passed them over and paid Cristofori a higher salary than his predecessor. Moreover, Pollens notes, “curiously, there are no records of bills submitted for Cristofori’s pianofortes … This could mean that Cristofori was expected to turn over the fruits of his experimentation to the court.” Lastly, the Prince was evidently fascinated with machines (he collected over forty clocks, in addition to a great variety of elaborate musical instruments), and would thus be naturally interested in the elaborate mechanical action that was at the core of Cristofori’s work on the piano.

Maffei’s interview reports Cristofori’s memory of his conversation with the Prince at this time:

- che fu detto al Principe, che non volevo; rispos’ egli il farò volere io.

which Giuliana Montanari (reference below) translates as:

- The prince was told that I did not wish to go; he replied that he would make me want to

This suggests that the Prince may have felt that Cristofori would be a prize recruit and was trying to charm him into accepting his offer; consistent again with the view that the Prince was attempting to recruit him as an inventor.

In any event, Cristofori agreed to the appointment, for a salary of 12 scudi per month. He moved rather quickly to Florence (May 1688; his job interview having taken place in March or April), was issued a house, complete with utensils and equipment, by the Grand Duke’s administration, and set to work. For the Prince, he tuned, maintained, and transported instruments; worked on his various inventions, and also did restoration work on valuable older harpsichords.

At this time, the Grand Dukes of Tuscany employed a large staff of about 100 artisans, who worked in the Galleria dei Lavori of the Uffizi. Cristofori’s initial work space was probably in this area, which did not please him. He later told Maffei:

- che da principio durava fatica ad andare nello stanzone in questo strepito

- It was hard for me to have to go into the big room with all that noise (tr. Montanari)

Cristofori did eventually obtain his own workshop, usually keeping one or two assistants working for him.

Earlier instruments

During the remaining years of the 17th century, Cristofori invented two keyboard instruments before he began his work on the piano. These instruments are documented in an inventory, dated 1700, of the many instruments kept by Prince Ferdinando. Stewart Pollens conjectures that this inventory was prepared by a court musician named Giovanni Fuga, who may have referred to it as his own in a 1716 letter.

The spinettone, Italian for “big spinet”, was a large, multi-choired spinet (a harpsichord in which the strings are slanted to save space), with disposition 1 x 8′, 1 x 4′; most spinets have the simple disposition 1 x 8′. This invention may have been meant to fit into a crowded orchestra pit for theatrical performances, while having the louder sound of a multi-choired instrument.

The other invention (1690) was the highly original oval spinet, a kind of virginal with the longest strings in the middle of the case.

Cristofori also built instruments of existing types, documented in the same 1700 inventory: a clavicytherium (upright harpsichord), and two harpsichords of the standard Italian 2 x 8′ disposition; one of them has an unusual case made of ebony.

The first appearance of the piano

It was thought for some time that the earliest mention of the piano is from a diary of Francesco Mannucci, a Medici court musician, indicating that Cristofori was already working on the piano by 1698. However, the authenticity of this document is now doubted. The first unambiguous evidence for the piano comes from the 1700 inventory of the Medici mentioned in the preceding section. The entry in this inventory for Cristofori’s piano begins as follows:

- Un Arpicembalo di Bartolomeo Cristofori di nuova inventione, che fa’ il piano, e il forte, a due registri principali unisoni, con fondo di cipresso senza rosa…” (boldface added)

- An “Arpicembalo” by Bartolomeo Cristofori, of new invention that produces soft and loud, with two sets of strings at unison pitch, with soundboard of cypress without rose…”

The term “Arpicembalo”, literally “harp-harpsichord”, was not generally familiar in Cristofori’s day. Edward Good infers that this is what Cristofori himself wanted his instrument to be called. Our own word for the piano, however, is the result of a gradual truncation over time of the words shown in boldface above.

The Medici inventory goes on to describe the instrument in considerable detail. The range of this (now lost) instrument was four octaves, C to c″″′, a standard (if slightly small) compass for harpsichords.

Another document referring to the earliest piano is a marginal note made by one of the Medici court musicians, Federigo Meccoli, in a copy of the book Le Istitutioni harmoniche by Gioseffo Zarlino. Meccoli wrote:

- These are the ways in which it is possible to play the Arpicimbalo del piano e forte, invented by Master Bartolomeo Christofani of Padua in the year 1700, harpsichord maker to the Most Serene Grand Prince Ferdinand of Tuscany. (transl. Stewart Pollens)

According to Scipione Maffei’s journal article, by 1711 Cristofori had built three pianos. The Medici had given one to Cardinal Ottoboni in Rome, and two had been sold in Florence.

Later life

Cristofori’s patron, Prince Ferdinando, died at the age of 50 in 1713. There is evidence that Cristofori continued to work for the Medici court, still headed by the Prince’s father Cosimo III. Specifically, a 1716 inventory of the musical instrument collection is signed “Bartolommeo Cristofori Custode”, indicating that Cristofori had been given the title of custodian of the collection.

During the early 18th century, the prosperity of the Medici princes declined, and like many of the other Medici-employed craftsmen, Cristofori took to selling his work to others. The king of Portugal bought at least one of his instruments.

In 1726, the only known portrait of Cristofori was painted (see above). It portrays the inventor standing proudly next to what is almost certainly a piano. In his left hand is a piece of paper, believed to contain a diagram of Cristofori’s piano action. The portrait was destroyed in the Second World War, and only photographs of it remain.

Cristofori continued to make pianos until near the end of his life, continually making improvements in his invention. In his senior years, he was assisted by Giovanni Ferrini, who went on to have his own distinguished career, continuing his master’s tradition. There is tentative evidence that there was another assistant, P. Domenico Dal Mela, who went on in 1739 to build the first upright piano.

In his declining years Cristofori prepared two wills. The first, dated January 24, 1729, bequeathed all his tools to Giovanni Ferrini. The second will, dated March 23 of the same year, changes the provisions substantially, bequeathing almost all his possessions to the “Dal Mela sisters … in repayment for their continued assistance lent to him during his illnesses and indispositions, and also in the name of charity.” This will left the small sum of five scudi to Ferrini. Pollens notes further evidence from the will that this reflected no falling out between Cristofori and Ferrini, but only Cristofori’s moral obligation to his caretakers. The inventor died on January 27, 1731 at the age of 75.

Cristofori’s pianos

The 1720 Cristofori piano in the Metropolitan Museum in New York

The 1722 Cristofori piano in the Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti Musicali in Rome.

The 1726 Cristofori piano in the Musikinstrumenten-Museum in Leipzig

The total number of pianos built by Cristofori is unknown. Only three survive today, all dating from the 1720s.

- A 1720 instrument is located in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Later builders have extensively altered this instrument: the soundboard was replaced in 1938, and the 54-note range was shifted by about half an octave, from F’, G’, A’–c”’ to C–f”. Although this piano is playable, according to builder Denzil Wraight “its original condition … has been irretrievably lost,” and it cannot indicate what it sounded like when new.

- A 1722 instrument is in the Museo Nazionale degli Strumenti Musicali in Rome. It has a range of four octaves (C-c³) and includes an “una corda” stop; see below. This piano has been damaged by worms and is not playable.

- A 1726 instrument is in the Musikinstrumenten-Museum of Leipzig University. Four octaves (C-c³) with “una corda” stop. This instrument is not currently playable, though in the past recordings were made.

The three surviving instruments all bear essentially the same Latin inscription: “BARTHOLOMAEVS DE CHRISTOPHORIS PATAVINUS INVENTOR FACIEBAT FLORENTIAE “, where the date is rendered in Roman numerals. The meaning is “Bartolomeo Cristofori of Padua, inventor, made in Florence in .”

Design

The piano as built by Cristofori in the 1720s boasted almost all of the features of the modern instrument. It differed in being of very light construction, lacking a metal frame; this meant that it could not produce an especially loud tone. This continued to be the rule for pianos until around 1820, when iron bracing was first introduced. Here are design details of Cristofori’s instruments:

Action

Piano actions are complex mechanical devices which impose very specific design requirements, virtually all of which were met by Cristofori’s action.

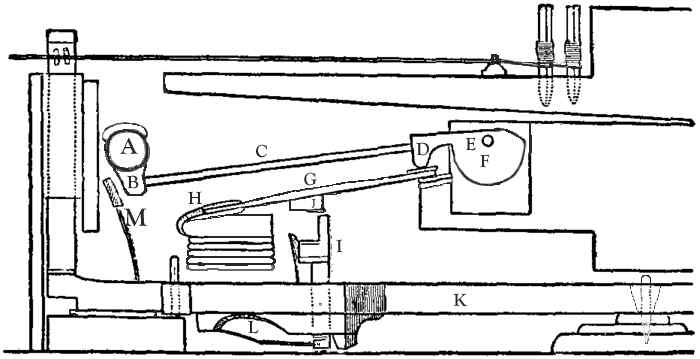

First, a piano action must be arranged so that a key press does not actually lift the hammer all the way to the string. If it did, the hammer would block on the string and damp its vibrations. The position of the sprung ‘hopper’ or ‘jack’ centred in the key of Cristofori’s action (see “I” in diagram below) is so adjusted that the hopper escapes from the ‘notch’ in the middle of the intermediate lever (G) just before the hammer (C) strikes the string, so that the hammer is not driven all the way but travels the remaining distance under its own momentum and then falls into the check (M). When the key is allowed to return to its position of rest, the jack springs back under the notch and a repeated blow is possible. Although Cristofori’s design incorporates no specific device for repetition, the lightness of the action gives more facility for repetition than the heavier actions of the English type that developed in the first half of the 19th century, until these were provided with additions of one kind or another to facilitate repetition.

Second, a piano action must greatly amplify the motion of the player’s finger: in Cristofori’s action, an intermediate lever (G) was used to translate every key motion into a hammer motion eight times greater in magnitude. Cristofori’s multiple-lever design succeeded in providing the needed leverage in a small amount of space.

Third, after the hammer strikes the string, the action must avoid an unwanted second blow, which could easily result from the hammer bouncing up and down within the space confining it. In Cristofori’s action, this was accomplished by two means. By lifting the intermediate lever with a jack that disengages in its highest position, the Cristofori action made it possible for the hammer to fall (after its initial blow) to a position considerably lower than the highest position to which the key had lifted it. By itself, this mechanism greatly reduces the chance of an unwanted second blow. Also, the Cristofori action included a check (also called “back check”; M) that catches the hammer and holds it in a partially raised position until the player releases the key; the check also helped to prevent unwanted second blows.

The Cristofori piano action

The complexity of Cristofori’s action and hence the difficulty of building it may have formed a barrier to later builders, who appear to have tried to simplify it. However, Cristofori’s design ultimately won out; the standard modern piano action is a still more complex and evolved version of Cristofori’s original.

Hammers

The hammer heads in Cristofori’s mature pianos (A) are made of paper, curled into a circular coil and secured with glue, and surmounted by a strip of leather at the contact point with the string. According to harpsichord maker and scholar Denzil Wraight, such hammers have their origin in “15th-century paper organ pipe technology”. The purpose of the leather is presumably to make the hammers softer, thus emphasizing the lower harmonics of string vibration by maintaining a broad area of contact at impact. The same goal of softness was achieved in later 18th-century pianos by covering the wooden hammers with soft leather, and in mid-19th-century and later instruments by covering a wooden core with a thick layer of compressed felt.

As in modern pianos, the hammers are larger in the bass notes than in the treble.

Frame

Cristofori’s pianos use an internal frame member (bentside) to support the soundboard; in other words, the structural member attaching the right side of the soundboard is distinct from the external case that bears the tension of the strings. Cristofori also applied this system to harpsichords. The use of a separate support for the soundboard reflects Cristofori’s belief that the soundboard should not be subjected to compression from string tension. This may improve the sound, and also avoids the peril of warping—as harpsichord makers Kerstin Schwarz and Tony Chinnery point out , , a severely warped soundboard threatens a structural catastrophe, namely contact between strings and soundboard. Cristofori’s principle continues to be applied in modern pianos, where the now-enormous string tension (up to 20 tons) is borne by a separate iron frame (the “plate”).

Wraight has written that the three surviving Cristofori pianos appear to follow an orderly progression: each has heavier framing than its predecessor. Wraight suggests that this would have been intentional, in that the heavier framing permitted tenser, thicker strings. This in turn increased the volume with which treble notes could be played without pitch distortion, a limitation that Wraight observes when playing replica instruments. Thus, it appears that the move toward heavier framing, a trend that dominates the history of the piano, may already have begun in Cristofori’s own building practice.

Inverted wrest plank

On two of his surviving instruments, Cristofori employed an unusual arrangement of the tuning pins: they are inserted all the way through their supporting wrest plank. Thus, the tuning hammer is used on the top side of the wrest plank, but the strings are wrapped around the pins on the bottom side. This made it harder to replace broken strings, but it provided two compensating advantages. With the nut (front bridge) inverted as well, the blows of the hammers, coming from below, would seat the strings firmly into place, rather than threatening to displace them. The inverted wrestplank also placed the strings lower in the instrument, permitting smaller and lighter hammers, hence a lighter and more responsive touch.

According to musical instrument scholar Grant O’Brien, the inverted wrestplank is “still to be found in pianos dating from a period 150 years after death.” In modern pianos, the same basic principle is followed: the contact point for the vibrating length of the string that is close to the hammers is either an agraffe or the capo d’astro bar; these devices pull the string in the direction opposite to the hammer blow, just as in Cristofori’s original arrangement.

Soundboard

Cristofori used cypress, the wood traditionally favored for soundboards in the Italian school of harpsichord making. Piano making after Cristofori’s time ultimately settled consistently on spruce as the best material for soundboards; however, Denzil Wraight has noted some compensating advantages for cypress.

Strings

In Cristofori’s pianos, there are two strings per note, throughout the compass. Modern pianos use three strings in the mid and upper range, two in the upper bass, and one in the lower bass, with greater variation in thickness than Cristofori used. The strings are equally spaced rather than being grouped with strings of identical pitch closer together.

In two of the attested pianos, there is a forerunner of the modern soft pedal: the player can manually slide the entire action four millimeters to one side, so that the hammers strike just one of the two strings (“una corda”). It is possible however that this device was intended as an aid to tuning. In his combined harpsichord-piano, with two 8-foot strings for each note, Ferrini allowed one set of harpsichord jacks to be disengaged but did not provide a una corda device for the hammer action.

The strings may have been thicker than harpsichord strings of the same period, although there are no original string gauge markings on any of the three surviving pianos to prove this. Thicker strings are thought to be better suited to the hammer blows. Comparing the two 1726 instruments, one a piano, the other a harpsichord, the lengths of the 8-foot strings are almost the same, certainly in the upper halves of the compasses of the two instruments.

It is difficult to determine what metal the strings of Cristofori’s pianos were made of, since strings are replaced as they break, and sometimes restorers even replace the entire set of strings. According to Stewart Pollens, “the earlier museum records document that all three Cristofori pianos were discovered with similar gauges of iron wire through much of the compass, and brass in the bass.” The New York instrument was restrung entirely in brass in 1970; Pollens reports that with this modification the instrument cannot be tuned closer than a minor third below pitch without breaking strings. This may indicate that the original strings did indeed include iron ones; however, the breakage might also be blamed on the massive rebuilding of this instrument, which changed its tonal range.

More recently, Denzil Wraight, Tony Chinnery, and Kerstin Schwarz, who have built replica Cristofori pianos, have taken the view that Cristofori favored brass strings, except occasionally in very demanding locations (such as the upper range of a 2′ harpsichord stop). Chinnery suggests that “cypress soundboards and brass strings go together: sweetness of sound rather than volume or brilliance.”

Sound

According to Wraight, it is not straightforward to determine what Cristofori’s pianos sounded like, since the surviving instruments (see above) are either too decrepit to be played or have been extensively and irretrievably altered in later “restorations”. However, in recent decades, many modern builders have made Cristofori replicas, and their collective experience, and particularly the recordings made on these instruments, has created an emerging view concerning the Cristofori piano sound. The sound of the Cristofori replicas is as close to the harpsichord as it is to the modern piano; this is to be expected given that their case construction and stringing are much closer to the harpsichord than to the piano. The note onsets are not as sharply defined as in a harpsichord, and the response of the instrument to the player’s varying touch is clearly noticeable.

Some Cristofori instruments—both restored and replicated—may be heard in the external links below.

Initial reception of the piano

Knowledge of how Cristofori’s invention was initially received comes in part from the article published in 1711 by Scipione Maffei, an influential literary figure, in the Giornale de’letterati d’Italia of Venice. Maffei said that “some professionals have not given this invention all the applause it merits,” and goes on to say that its sound was felt to be too “soft” and “dull”—Cristofori was unable to make his instrument as loud as the competing harpsichord. Yet Maffei himself was an enthusiast for the piano, and the instrument did gradually catch on and increase in popularity, in part due to Maffei’s efforts.

One reason why the piano spread slowly at first was that it was quite expensive to make, and thus was purchased only by royalty and a few wealthy private individuals. The ultimate success of Cristofori’s invention occurred only in the 1760s, when the invention of cheaper square pianos, along with generally greater prosperity, made it possible for many people to acquire one.

Subsequent technological developments in the piano were often mere “re-inventions” of Cristofori’s work; in the early years, there were perhaps as many regressions as advances.

Surviving instruments

The 1693 oval spinet, in the collections of the Museum für Musikinstrumente in Leipzig, Germany

Cristofori spinettone in the Leipzig museum

Nine instruments that survive today are attributed to Cristofori:

The 1726 harpsichord with disposition 1 x 8′, 1 x 4′, 1 x 2′, in the Leipzig museum. There are three separate bridges and three separate nuts for the eight-foot, four-foot, and two-foot string choirs.

- The three pianos described above.

- Two oval spinets, from 1690 and 1693. The 1690 instrument is kept in the Museo degli strumenti musicali, part of the Galleria del Accademia in Florence. The 1693 oval spinet is in the Musikinstrumenten-Museum of the University of Leipzig.

- A spinettone, also in the Leipzig museum.

- An early (17th century) harpsichord, with a case made of ebony. It is kept in the Museo degli strumenti musicali in Florence (part of the Galleria dell’Accademia). An image can be viewed at the website of harpsichord builder Tony Chinnery.

- A harpsichord dated 1722, in the Leipzig museum.

- A 1726 harpsichord, in the Leipzig museum. It has the disposition 1 x 8′, 1 x 4′, 1 x 2′ and is the only known Italian harpsichord with a two-foot stop. The instrument illustrates Cristofori’s ingenuity in the large number of levers and extensions that permit the player great flexibility in determining which strings will sound. There are six basic registrations: 8′, 8’+4′, 4′, 4’+2′, 2′, 8’+ 4’+2′; in addition, the player may add 4′, 2′ or 4’+2′ to the 8′ stop just in notes of the bass range.

The later instruments, dating from Cristofori’s old age, probably include work by assistant Giovanni Ferrini, who went on after the inventor’s death to build pianos of wider range using the same basic design.

An apparent remnant harpsichord, lacking soundboard, keyboard, and action, is currently the property of the noted builder Tony Chinnery, who acquired it at an auction in New York. This instrument passed through the shop of the late 19th century builder/fraudster Leopoldo Franciolini, who reworked it with his characteristic form of decoration, but according to Chinnery “there are enough construction details to identify it definitely as the work of Cristofori”.

There are also several fraudulent instruments attributed to Cristofori, notably a three-manual harpsichord once displayed in the Deutsches Museum in Munich; this was a rebuilding by Franciolini of a single-manual instrument made in 1658 by Girolamo Zenti.

Assessments of Cristofori

Cristofori was evidently admired and respected in his own lifetime for his work on the piano. On his death, a theorbo player at the Medici court named Niccolò Susier wrote in his diary:

- 1731, 27th , Bartolomeo Crisofani , called Bartolo Padovano, died, famous instrument maker to the Most Serene Grand Prince Ferdinando of fond memory, and he was a skillful maker of keyboard instruments, and also the inventor of the pianoforte, that is known through all Europe, and who served His Majesty the King of Portugal , who paid two hundred gold louis d’or for the said instruments, and he died, as has been said, at the age of eighty-one years.

An anonymous 18th-century music dictionary, found in the library of the composer Padre G. B. Martini, says of him

- Christofori Bartolomeo of Padua died in Florence was the famous harpsichord maker, a distinguished restorer rendering even better good instruments made by other past masters and he was also the inventor of harpsichords with hammers, which produce a different quality of sound both on account of the hammer striking the chord and the completely different internal structure of the body of the instrument, not visible from the outside the best instruments that he made were for Ferdinando de’ Medici Great Prince of Tuscany, his protector and son of the Grand Duke Cosimo III.

After his death, however, Cristofori’s reputation went into decline. As Stewart Pollens has documented, in late 18th century France it was believed that the piano had been invented not by Cristofori but by the German builder Gottfried Silbermann. Silbermann was in fact an important figure in the history of the piano, but his instruments relied almost entirely on Cristofori for the design of their hammer actions. Later scholarship (notably by Leo Puliti) only gradually corrected this error.

In the second half of the 20th century, Cristofori’s instruments were studied with care, as part of the general increase in interest in early instruments that developed in this era (see authentic performance). The modern scholars who have studied Cristofori’s work in detail tend to express their admiration in the strongest terms; thus the New Grove encyclopedia describes him as having possessed “tremendous ingenuity”; Stewart Pollens says “All of Cristofori’s work is startling in its ingenuity”; and the early-instrument scholar Grant O’Brien has written “The workmanship and inventiveness displayed by the instruments of Cristofori are of the highest order and his genius has probably never been surpassed by any other keyboard maker of the historical period … I place Cristofori shoulder to shoulder with Antonio Stradivarius.”

Cristofori is also given credit for originality in inventing the piano. While it is true that there had been earlier, crude attempts to make piano-like instruments, it is not clear that these were even known to Cristofori. The piano is thus an unusual case in which an important invention can be ascribed unambiguously to a single individual, who brought it to an unusual degree of perfection all on his own.

See also

- List of historical harpsichord makers

Notes

- ^ Pollens, 995, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Pollens, 1995, p. 51.

- ^ For the latter work, see reference by Grant O’Brien under External Links below

- ^ The inventory is published in Gai 1969.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c van der Meer 2005, 275

- ^ Jump up to:a b Hubbard 1967, Chapter 1

- ^ The scholarly situation is summarized by Montanari (1991): excerpts from the Mannucci diary, entitled “Per mio ricordo Memoria di Francesco M. Mannucci Fiorentino A di 16 febbraio 1710 ab Inc Laus Deo,” were published by M. Fabri (1964). Fabri noted the location of the diary in the San Lorenzo archive, but subsequent searching by other scholars never found it. Later, Furnari and Vitali (1991) found that the diary claimed that Scipione Maffei was in Florence at a time contradicted by Maffei’s own preserved correspondence, and pointed out other reasons to doubt the diary’s authenticity. Their doubts seem to have convinced other scholars (see references by O’Brian and Pollens (1995) below), and the diary—along with its 1698 date for the invention of the piano—is not relied on in the most current reference sources.

- ^ Good (2005)

- ^ Pitch given in Helmholtz pitch notation

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Wraight (2006, 635)

- ^ Pollens (1991, 78)

- ^ Wraight (2006, 638)

- ^ Claviatica.com

- ^ Gutenberg.com

- ^ Vogel (2003:11) notes several aspects of the modern piano action that were already employed by Cristofori (“moveable jack, single escapement, intermediate level, back check, upper damper”), citing them as “visible proof of Cristofori’s genius” and observing that a number of these parts were “re-invented” during the evolution of the piano.

- ^ The count is from Kottick (2003, 211), who lists eight but wrote just before the discovery of the ninth, the 1690 oval spinet.

- ^ Kottick and Lucktenberg (1997, 99)

- ^ Image and commentary on BBC website

- ^ Denzil Wraight (1991) “A Zenti harpsichord rediscovered”. Early Music 191:99–102.

- ^ Puliti 1874

- ^ Pollens (1995:45–46)