Dalai Lama (UK: /ˈdælaɪ ˈlɑːmə/, US: /ˈdɑːlaɪ/; Tibetan: ཏཱ་ལའི་བླ་མ་, Wylie: Tā la’i bla ma ) is a title given by the Tibetan people to the foremost spiritual leader of the Gelug or “Yellow Hat” school of Tibetan Buddhism, the newest and most dominant of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The 14th and current Dalai Lama is Tenzin Gyatso, who lives as a refugee in India. The Dalai Lama is also considered to be the successor in a line of tulkus who are believed to be incarnations of Avalokiteśvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion.

Since the time of the 5th Dalai Lama in the 17th century, his personage has always been a symbol of unification of the state of Tibet, where he has represented Buddhist values and traditions. The Dalai Lama was an important figure of the Geluk tradition, which was politically and numerically dominant in Central Tibet, but his religious authority went beyond sectarian boundaries. While he had no formal or institutional role in any of the religious traditions, which were headed by their own high lamas, he was a unifying symbol of the Tibetan state, representing Buddhist values and traditions above any specific school. The traditional function of the Dalai Lama as an ecumenical figure, holding together disparate religious and regional groups, has been taken up by the fourteenth Dalai Lama. He has worked to overcome sectarian and other divisions in the exiled community and has become a symbol of Tibetan nationhood for Tibetans both in Tibet and in exile.

From 1642 until 1705 and from 1750 to the 1950s, the Dalai Lamas or their regents headed the Tibetan government (or Ganden Phodrang) in Lhasa, which governed all or most of the Tibetan Plateau with varying degrees of autonomy. This Tibetan government enjoyed the patronage and protection of firstly Mongol kings of the Khoshut and Dzungar Khanates (1642–1720) and then of the emperors of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty (1720–1912). In 1913, several Tibetan representatives including Agvan Dorzhiev signed a treaty between Tibet and Mongolia, proclaiming mutual recognition and their independence from China, however the legitimacy of the treaty and declared independence of Tibet was rejected by both the Republic of China and the current People’s Republic of China. The Dalai Lamas headed the Tibetan government afterwards despite that, until 1951.

Names

The name “Dalai Lama” is a combination of the Mongolic word dalai meaning “ocean” or “big” (coming from Mongolian title Dalaiyin qan or Dalaiin khan, translated as Gyatso or rgya-mtsho in Tibetan) and the Tibetan word བླ་མ་ (bla-ma) meaning “master, guru”.

The Dalai Lama is also known in Tibetan as the Rgyal-ba Rin-po-che (“Precious Conqueror”) or simply as the Rgyal-ba.: 23

History

| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

In Central Asian Buddhist countries, it has been widely believed for the last millennium that Avalokiteśvara, the bodhisattva of compassion, has a special relationship with the people of Tibet and intervenes in their fate by incarnating as benevolent rulers and teachers such as the Dalai Lamas. This is according to The Book of Kadam, the main text of the Kadampa school, to which the 1st Dalai Lama, Gendun Drup, first belonged. In fact, this text is said to have laid the foundation for the Tibetans’ later identification of the Dalai Lamas as incarnations of Avalokiteśvara.

It traces the legend of the bodhisattva’s incarnations as early Tibetan kings and emperors such as Songtsen Gampo and later as Dromtönpa (1004–1064).

This lineage has been extrapolated by Tibetans up to and including the Dalai Lamas.

Origins in myth and legend

Thus, according to such sources, an informal line of succession of the present Dalai Lamas as incarnations of Avalokiteśvara stretches back much further than Gendun Drub. The Book of Kadam, the compilation of Kadampa teachings largely composed around discussions between the Indian sage Atiśa (980–1054) and his Tibetan host and chief disciple Dromtönpa and Tales of the Previous Incarnations of Arya Avalokiteśvara, nominate as many as sixty persons prior to Gendun Drub who are enumerated as earlier incarnations of Avalokiteśvara and predecessors in the same lineage leading up to him. In brief, these include a mythology of 36 Indian personalities plus 10 early Tibetan kings and emperors, all said to be previous incarnations of Dromtönpa, and fourteen further Nepalese and Tibetan yogis and sages in between him and the 1st Dalai Lama. In fact, according to the “Birth to Exile” article on the 14th Dalai Lama’s website, he is “the seventy-fourth in a lineage that can be traced back to a Brahmin boy who lived in the time of Buddha Shakyamuni.”

Avalokiteśvara’s “Dalai Lama master plan”

According to the 14th Dalai Lama, long ago Avalokiteśvara had promised the Buddha to guide and defend the Tibetan people and in the late Middle Ages, his master plan to fulfill this promise was the stage-by-stage establishment of the Dalai Lama theocracy in Tibet.

First, Tsongkhapa established three great monasteries around Lhasa in the province of Ü before he died in 1419. The 1st Dalai Lama soon became Abbot of the greatest one, Drepung, and developed a large popular power base in Ü. He later extended this to cover Tsang, where he constructed a fourth great monastery, Tashi Lhunpo, at Shigatse. The 2nd studied there before returning to Lhasa, where he became Abbot of Drepung. Having reactivated the 1st’s large popular followings in Tsang and Ü, the 2nd then moved on to southern Tibet and gathered more followers there who helped him construct a new monastery, Chokorgyel. He also established the method by which later Dalai Lama incarnations would be discovered through visions at the “oracle lake”, Lhamo Lhatso. The 3rd built on his predecessors’ fame by becoming Abbot of the two great monasteries of Drepung and Sera. The stage was set for the great Mongol King Altan Khan, hearing of his reputation, to invite the 3rd to Mongolia where he converted the King and his followers to Buddhism, as well as other Mongol princes and their followers covering a vast tract of central Asia. Thus most of Mongolia was added to the Dalai Lama’s sphere of influence, founding a spiritual empire which largely survives to the modern age. After being given the Mongolian name ‘Dalai’, he returned to Tibet to found the great monasteries of Lithang in Kham, eastern Tibet and Kumbum in Amdo, north-eastern Tibet. The 4th was then born in Mongolia as the great-grandson of Altan Khan, thus cementing strong ties between Central Asia, the Dalai Lamas, the Gelugpa and Tibet. Finally, in fulfilment of Avalokiteśvara’s master plan, the 5th in the succession used the vast popular power base of devoted followers built up by his four predecessors. By 1642, a strategy that was planned and carried out by his resourceful chagdzo or manager Sonam Rapten with the military assistance of his devoted disciple Gushri Khan, Chieftain of the Khoshut Mongols, enabled the ‘Great 5th’ to found the Dalai Lamas’ religious and political reign over more or less the whole of Tibet that survived for over 300 years.

Thus the Dalai Lamas became pre-eminent spiritual leaders in Tibet and 25 Himalayan and Central Asian kingdoms and countries bordering Tibet and their prolific literary works have “for centuries acted as major sources of spiritual and philosophical inspiration to more than fifty million people of these lands”. Overall, they have played “a monumental role in Asian literary, philosophical and religious history”.

Establishment of the Dalai Lama lineage

Gendun Drup (1391–1474), a disciple of the founder Je Tsongkapa, was the ordination name of the monk who came to be known as the ‘First Dalai Lama’, but only from 104 years after he died. There had been resistance, since first he was ordained a monk in the Kadampa tradition and for various reasons, for hundreds of years the Kadampa school had eschewed the adoption of the tulku system to which the older schools adhered. Tsongkhapa largely modelled his new, reformed Gelugpa school on the Kadampa tradition and refrained from starting a tulku system. Therefore, although Gendun Drup grew to be a very important Gelugpa lama, after he died in 1474 there was no question of any search being made to identify his incarnation.

Despite this, when the Tashilhunpo monks started hearing what seemed credible accounts that an incarnation of Gendun Drup had appeared nearby and repeatedly announced himself from the age of two, their curiosity was aroused. It was some 55 years after Tsongkhapa’s death when eventually, the monastic authorities saw compelling evidence that convinced them the child in question was indeed the incarnation of their founder. They felt obliged to break with their own tradition and in 1487, the boy was renamed Gendun Gyatso and installed at Tashilhunpo as Gendun Drup’s tulku, albeit informally.

Gendun Gyatso died in 1542 and the lineage of Dalai Lama tulkus finally became firmly established when the third incarnation, Sonam Gyatso (1543–1588), came forth. He made himself known as the tulku of Gendun Gyatso and was formally recognised and enthroned at Drepung in 1546. When Gendun Gyatso was given the titular name “Dalai Lama” by the Tümed Altan Khan in 1578,: 153 his two predecessors were accorded the title posthumously and he became known as the third in the lineage.

1st Dalai Lama

The Dalai Lama lineage started from humble beginnings. ‘Pema Dorje’ (1391–1474), the boy who was to become the first in the line, was born in a cattle pen in Shabtod, Tsang in 1391. His nomad parents kept sheep and goats and lived in tents. When his father died in 1398 his mother was unable to support the young goatherd so she entrusted him to his uncle, a monk at Narthang, a major Kadampa monastery near Shigatse, for education as a Buddhist monk. Narthang ran the largest printing press in Tibet and its celebrated library attracted scholars and adepts from far and wide, so Pema Dorje received an education beyond the norm at the time as well as exposure to diverse spiritual schools and ideas. He studied Buddhist philosophy extensively and in 1405, ordained by Narthang’s abbot, he took the name of Gendun Drup. Soon recognised as an exceptionally gifted pupil, the abbot tutored him personally and took special interest in his progress. In 12 years he passed the 12 grades of monkhood and took the highest vows. After completing his intensive studies at Narthang he left to continue at specialist monasteries in Central Tibet, his grounding at Narthang was revered among many he encountered.

In 1415 Gendun Drup met Tsongkhapa, founder of the Gelugpa school, and became his student; their meeting was of decisive historical and political significance as he was later to be known as the 1st Dalai Lama. When eventually Tsongkhapa’s successor the Panchen Lama Khedrup Je died, Gendun Drup became the leader of the Gelugpa. He rose to become Abbot of Drepung, the greatest Gelugpa monastery, outside Lhasa.

It was mainly due to Gendun Drup’s energy and ability that Tsongkhapa’s new school grew into an expanding order capable of competing with others on an equal footing. Taking advantage of good relations with the nobility and a lack of determined opposition from rival orders, on the very edge of Karma Kagyu-dominated territory he founded Tashilhunpo Monastery at Shigatse. He was based there, as its Abbot, from its founding in 1447 until his death. Tashilhunpo, ‘Mountain of Blessings’, became the fourth great Gelugpa monastery in Tibet, after Ganden, Drepung and Sera had all been founded in Tsongkhapa’s time. It later became the seat of the Panchen Lamas. By establishing it at Shigatse in the middle of Tsang, he expanded the Gelugpa sphere of influence, and his own, from the Lhasa region of Ü to this province, which was the stronghold of the Karma Kagyu school and their patrons, the rising Tsangpa dynasty. Tashilhunpo was destined to become ‘Southern Tibet’s greatest monastic university’ with a complement of 3,000 monks.

Gendun Drup was said to be the greatest scholar-saint ever produced by Narthang Monastery and became ‘the single most important lama in Tibet’. Through hard work he became a leading lama, known as ‘Perfecter of the Monkhood’, ‘with a host of disciples’. Famed for his Buddhist scholarship he was also referred to as Panchen Gendun Drup, ‘Panchen’ being an honorary title designating ‘great scholar’. By the great Jonangpa master Bodong Chokley Namgyal he was accorded the honorary title Tamchey Khyenpa meaning “The Omniscient One”, an appellation that was later assigned to all Dalai Lama incarnations.

At the age of 50, he entered meditation retreat at Narthang. As he grew older, Karma Kagyu adherents, finding their sect was losing too many recruits to the monkhood to burgeoning Gelugpa monasteries, tried to contain Gelug expansion by launching military expeditions against them in the region. This led to decades of military and political power struggles between Tsangpa dynasty forces and others across central Tibet. In an attempt to ameliorate these clashes, from his retreat Gendun Drup issued a poem of advice to his followers advising restraint from responding to violence with more violence and to practice compassion and patience instead. The poem, entitled Shar Gang Rima, “The Song of the Eastern Snow Mountains”, became one of his most enduring popular literary works.

Although he was born in a cattle pen to be a simple goatherd, Gendun Drup rose to become one of the most celebrated and respected teachers in Tibet and Central Asia. His spiritual accomplishments brought him substantial donations from devotees which he used to build and furnish new monasteries, to print and distribute Buddhist texts and to maintain monks and meditators. At last, at the age of 84, older than any of his 13 successors, in 1474 he went on foot to visit Narthang Monastery on a final teaching tour. Returning to Tashilhunpo he died ‘in a blaze of glory, recognised as having attained Buddhahood’.

His mortal remains were interred in a bejewelled silver stupa at Tashi Lhunpo Monastery, which survived the Cultural Revolution and can still be seen.

2nd Dalai Lama

Like the Kadampa, the Gelugpa eschewed the tulku system. After Gendun Drup died, however, a boy called Sangyey Pel born to Nyngma adepts at Yolkar in Tsang, declared himself at 3 to be “Gendun Drup” and asked to be ‘taken home’ to Tashilhunpo. He spoke in mystical verses, quoted classical texts out of the blue and said he was Dromtönpa, an earlier incarnation of the Dalai Lamas. When he saw monks from Tashilhunpo he greeted the disciples of the late Gendun Drup by name. The Gelugpa elders had to break with tradition and recognised him as Gendun Drup’s tulku.

He was then 8, but until his 12th year his father took him on his teachings and retreats, training him in all the family Nyingma lineages. At 12 he was installed at Tashilhunpo as Gendun Drup’s incarnation, ordained, enthroned and renamed Gendun Gyatso Palzangpo (1475–1542).

Tutored personally by the abbot he made rapid progress and from 1492 at 17 he was requested to teach all over Tsang, where thousands gathered to listen and give obeisance, including senior scholars and abbots. In 1494, at 19, he met some opposition from the Tashilhunpo establishment when tensions arose over conflicts between advocates of the two types of succession, the traditional abbatial election through merit, and incarnation. Although he had served for some years as Tashilhunpo’s abbot, he therefore moved to central Tibet, where he was invited to Drepung and where his reputation as a brilliant young teacher quickly grew. He was accorded all the loyalty and devotion that Gendun Drup had earned and the Gelug school remained as united as ever. This move had the effect of shifting central Gelug authority back to Lhasa. Under his leadership, the sect went on growing in size and influence and with its appeal of simplicity, devotion and austerity its lamas were asked to mediate in disputes between other rivals.

Gendun Gyatso’s popularity in Ü-Tsang grew as he went on pilgrimage, travelling, teaching and studying from masters such as the adept Khedrup Norzang Gyatso in the Olklha mountains. He also stayed in Kongpo and Dagpo and became known all over Tibet. He spent his winters in Lhasa, writing commentaries and the rest of the year travelling and teaching many thousands of monks and lay people.

In 1509 he moved to southern Tibet to build Chokorgyel Monastery near the ‘Oracle Lake’, Lhamo Latso, completing it by 1511. That year he saw visions in the lake and ’empowered’ it to impart clues to help identify incarnate lamas. All Dalai Lamas from the 3rd on were found with the help of such visions granted to regents. By now widely regarded as one of Tibet’s greatest saints and scholars he was invited back to Tashilhunpo. On his return in 1512, he was given the residence built for Gendun Drup, to be occupied later by the Panchen Lamas. He was made abbot of Tashilhunpo and stayed there teaching in Tsang for 9 months.

Gendun Gyatso continued to travel widely and teach while based at Tibet’s largest monastery, Drepung and became known as ‘Drepung Lama’, his fame and influence spreading all over Central Asia as the best students from hundreds of lesser monasteries in Asia were sent to Drepung for education.

Throughout Gendun Gyatso’s life, the Gelugpa were opposed and suppressed by older rivals, particularly the Karma Kagyu and their Ringpung clan patrons from Tsang, who felt threatened by their loss of influence. In 1498 the Ringpung army captured Lhasa and banned the Gelugpa annual New Year Monlam Prayer Festival started by Tsongkhapa for world peace and prosperity. Gendun Gyatso was promoted to abbot of Drepung in 1517 and that year Ringpung forces were forced to withdraw from Lhasa. Gendun Gyatso then went to the Gongma (King) Drakpa Jungne to obtain permission for the festival to be held again. The next New Year, the Gongma was so impressed by Gendun Gyatso’s performance leading the Festival that he sponsored construction of a large new residence for him at Drepung, ‘a monastery within a monastery’. It was called the Ganden Phodrang, a name later adopted by the Tibetan Government, and it served as home for Dalai Lamas until the Fifth moved to the Potala Palace in 1645.

In 1525, already abbot of Chokhorgyel, Drepung and Tashilhunpo, he was made abbot of Sera monastery as well, and seeing the number of monks was low he worked to increase it. Based at Drepung in winter and Chokorgyel in summer, he spent his remaining years in composing commentaries, regional teaching tours, visiting Tashilhunpo from time to time and acting as abbot of these four great monasteries. As abbot, he made Drepung the largest monastery in the whole of Tibet. He attracted many students and disciples ‘from Kashmir to China’ as well as major patrons and disciples such as Gongma Nangso Donyopa of Droda who built a monastery at Zhekar Dzong in his honour and invited him to name it and be its spiritual guide.

Gongma Gyaltsen Palzangpo of Khyomorlung at Tolung and his Queen Sangyey Paldzomma also became his favourite devoted lay patrons and disciples in the 1530s and he visited their area to carry out rituals as ‘he chose it for his next place of rebirth’. He died in meditation at Drepung in 1542 at 67 and his reliquary stupa was constructed at Khyomorlung. It was said that, by the time he died, through his disciples and their students, his personal influence covered the whole of Buddhist Central Asia where ‘there was nobody of any consequence who did not know of him’.

3rd Dalai Lama

The Third Dalai Lama, Sonam Gyatso (1543–1588) was born in Tolung, near Lhasa, as predicted by his predecessor. Claiming he was Gendun Gyatso and readily recalling events from his previous life, he was recognised as the incarnation, named ‘Sonam Gyatso’ and installed at Drepung, where ‘he quickly excelled his teachers in knowledge and wisdom and developed extraordinary powers’. Unlike his predecessors, he came from a noble family, connected with the Sakya and the Phagmo Drupa (Karma Kagyu affiliated) dynasties, and it is to him that the effective conversion of Mongolia to Buddhism is due.

A brilliant scholar and teacher, he had the spiritual maturity to be made Abbot of Drepung, taking responsibility for the material and spiritual well-being of Tibet’s largest monastery at the age of nine. At 10 he led the Monlam Prayer Festival, giving daily discourses to the assembly of all Gelugpa monks. His influence grew so quickly that soon the monks at Sera Monastery also made him their Abbot and his mediation was being sought to prevent fighting between political power factions. At 16, in 1559, he was invited to Nedong by King Ngawang Tashi Drakpa, a Karma Kagyu supporter, and became his personal teacher. At 17, when fighting broke out in Lhasa between Gelug and Kagyu parties and efforts by local lamas to mediate failed, Sonam Gyatso negotiated a peaceful settlement. At 19, when the Kyichu River burst its banks and flooded Lhasa, he led his followers to rescue victims and repair the dykes. He then instituted a custom whereby on the last day of Monlam, all the monks would work on strengthening the flood defences. Gradually, he was shaping himself into a national leader. His popularity and renown became such that in 1564 when the Nedong King died, it was Sonam Gyatso at the age of 21 who was requested to lead his funeral rites, rather than his own Kagyu lamas.

Required to travel and teach without respite after taking full ordination in 1565, he still maintained extensive meditation practices in the hours before dawn and again at the end of the day. In 1569, at age 26, he went to Tashilhunpo to study the layout and administration of the monastery built by his predecessor Gendun Drup. Invited to become the Abbot he declined, already being Abbot of Drepung and Sera, but left his deputy there in his stead. From there he visited Narthang, the first monastery of Gendun Drup and gave numerous discourses and offerings to the monks in gratitude.

Meanwhile, Altan Khan, chief of all the Mongol tribes near China’s borders, had heard of Sonam Gyatso’s spiritual prowess and repeatedly invited him to Mongolia. By 1571, when Altan Khan received a title of Shunyi Wang (King) from the Ming dynasty of China and swore allegiance to Ming, although he remained de facto quite independent,: 106 he had fulfilled his political destiny and a nephew advised him to seek spiritual salvation, saying that “in Tibet dwells Avalokiteshvara”, referring to Sonam Gyatso, then 28 years old. China was also happy to help Altan Khan by providing necessary translations of holy scripture, and also lamas. At the second invitation, in 1577–78 Sonam Gyatso travelled 1,500 miles to Mongolia to see him. They met in an atmosphere of intense reverence and devotion and their meeting resulted in the re-establishment of strong Tibet-Mongolia relations after a gap of 200 years. To Altan Khan, Sonam Gyatso identified himself as the incarnation of Drogön Chögyal Phagpa, and Altan Khan as that of Kubilai Khan, thus placing the Khan as heir to the Chingizid lineage whilst securing his patronage. Altan Khan and his followers quickly adopted Buddhism as their state religion, replacing the prohibited traditional Shamanism. Mongol law was reformed to accord with Tibetan Buddhist law. From this time Buddhism spread rapidly across Mongolia and soon the Gelugpa had won the spiritual allegiance of most of the Mongolian tribes. As proposed by Sonam Gyatso, Altan Khan sponsored the building of Thegchen Chonkhor Monastery at the site of Sonam Gyatso’s open-air teachings given to the whole Mongol population. He also called Sonam Gyatso “Dalai”, Mongolian for ‘Gyatso’ (Ocean). In October 1587, as requested by the family of Altan Khan, Gyalwa Sonam Gyatso was promoted to Duǒ Er Zhǐ Chàng (Chinese:朵儿只唱) by the emperor of China, seal of authority and golden sheets were granted.

The name “Dalai Lama”, by which the lineage later became known throughout the non-Tibetan world, was thus established and it was applied to the first two incarnations retrospectively.

Returning eventually to Tibet by a roundabout route and invited to stay and teach all along the way, in 1580 Sonam Gyatso was in Hohhot , not far from Beijing, when the Chinese Emperor invited him to his court. By then he had established a religious empire of such proportions that it was unsurprising the Emperor wanted to invite him and grant him a diploma. At the request of the Ningxia Governor he had been teaching large gatherings of people from East Turkestan, Mongolia and nearby areas of China, with interpreters provided by the governor for each language. While there, a Ming court envoy came with gifts and a request to visit the Wanli Emperor but he declined having already agreed to visit Eastern Tibet next. Once there, in Kham, he founded two more great Gelugpa monasteries, the first in 1580 at Lithang where he left his representative before going on to Chamdo Monastery where he resided and was made Abbot. Through Altan Khan, the 3rd Dalai Lama requested to pay tribute to the Emperor of China in order to raise his State Tutor ranking, the Ming imperial court of China agreed with the request. In 1582, he heard Altan Khan had died and invited by his son Dhüring Khan he decided to return to Mongolia. Passing through Amdo, he founded a second great monastery, Kumbum, at the birthplace of Tsongkhapa near Kokonor. Further on, he was asked to adjudicate on border disputes between Mongolia and China. It was the first time a Dalai Lama had exercised such political authority. Arriving in Mongolia in 1585, he stayed 2 years with Dhüring Khan, teaching Buddhism to his people and converting more Mongol princes and their tribes. Receiving a second invitation from the Emperor in Beijing he accepted, but died en route in 1588. As he was dying, his Mongolian converts urged him not to leave them, as they needed his continuing religious leadership. He promised them he would be incarnated next in Mongolia, as a Mongolian.

4th Dalai Lama

The Fourth Dalai Lama, Yonten Gyatso (1589–1617) was a Mongolian, the great-grandson of Altan Khan who was a descendant of Kublai Khan and King of the Tümed Mongols who had already been converted to Buddhism by the Third Dalai Lama, Sonam Gyatso (1543–1588). This strong connection caused the Mongols to zealously support the Gelugpa sect in Tibet, strengthening their status and position but also arousing intensified opposition from the Gelugpa’s rivals, particularly the Tsang Karma Kagyu in Shigatse and their Mongolian patrons and the Bönpo in Kham and their allies. Being the newest school, unlike the older schools the Gelugpa lacked an established network of Tibetan clan patronage and were thus more reliant on foreign patrons. At the age of 10 with a large Mongol escort he travelled to Lhasa where he was enthroned. He studied at Drepung and became its abbot but being a non-Tibetan he met with opposition from some Tibetans, especially the Karma Kagyu who felt their position was threatened by these emerging events; there were several attempts to remove him from power. Yonten Gyatso died at the age of 27 under suspicious circumstances and his chief attendant Sonam Rapten went on to discover the 5th Dalai Lama, became his chagdzo or manager and after 1642 he went on to be his regent, the Desi.

5th Dalai Lama

11th Dalai Lama

Born in Gathar, Kham in 1838 and soon discovered by the official search committee with the help of the Nechung Oracle, the Eleventh Dalai Lama was brought to Lhasa in 1841 and recognised, enthroned and named Khedrup Gyatso by the Panchen Lama in 1842, who also ordained him in 1846. After that he was immersed in religious studies under the Panchen Lama, amongst other great masters. Meanwhile, there were court intrigues and ongoing power struggles taking place between the various Lhasa factions, the Regent, the Kashag, the powerful nobles and the abbots and monks of the three great monasteries. The Tsemonling Regent became mistrusted and was forcibly deposed, there were machinations, plots, beatings and kidnappings of ministers and so forth, resulting at last in the Panchen Lama being appointed as interim Regent to keep the peace. Eventually the Third Reting Rinpoche was made Regent, and in 1855, Khedrup Gyatso, appearing to be an extremely promising prospect, was requested to take the reins of power at the age of 17. He was enthroned as ruler of Tibet in 1855, on orders of the Xianfeng Emperor. He died after just 11 months, no reason for his sudden and premature death being given in these accounts, Shakabpa and Mullin’s histories both being based on untranslated Tibetan chronicles. The respected Reting Rinpoche was recalled once again to act as Regent and requested to lead the search for the next incarnation, the twelfth.

12th Dalai Lama

In 1856, a child was born in south central Tibet amidst all the usual extraordinary signs. He came to the notice of the search team, was investigated, passed the traditional tests and was recognised as the 12th Dalai Lama in 1858. The use of the Chinese Golden Urn at the insistence of the Regent, who was later accused of being a Chinese lackey, confirmed this choice to the satisfaction of all. Renamed Trinley Gyatso and enthroned in 1860 the boy underwent 13 years of intensive tutelage and training before stepping up to rule Tibet at the age of 17.

His minority seems a time of even deeper Lhasan political intrigue and power struggles than his predecessor’s. By 1862 this led to a coup by Wangchuk Shetra, a minister whom the Regent had banished for conspiring against him. Shetra contrived to return, deposed the Regent, who fled to China, and seized power, appointing himself ‘Desi’ or Prime Minister. He then ruled with “absolute power” for three years, quelling a major rebellion in northern Kham in 1863 and re-establishing Tibetan control over significant Qing-held territory there. Shetra died in 1864 and the Kashag re-assumed power. The retired 76th Ganden Tripa, Khyenrab Wangchuk, was appointed as ‘Regent’ but his role was limited to supervising and mentoring Trinley Gyatso.

In 1868 Shetra’s coup organiser, a semi-literate Ganden monk named Palden Dondrup, seized power by another coup and ruled as a cruel despot for three years, putting opponents to death by having them ‘sewn into fresh animal skins and thrown in the river’. In 1871, at the request of officials outraged after Dondrup had done just that with one minister and imprisoned several others, he in turn was ousted and committed suicide after a counter-coup coordinated by the supposedly powerless ‘Regent’ Khyenrab Wangchuk. As a result of this action this venerable old Regent, who died the next year, is fondly remembered by Tibetans as saviour of the Dalai Lama and the nation. The Kashag and the Tsongdu or National Assembly were re-instated, and, presided over by a Dalai Lama or his Regent, ruled without further interruption until 1959.

According to Smith, however, during Trinley Gyatso’s minority, the Regent was deposed in 1862 for abuse of authority and closeness with China, by an alliance of monks and officials called Gandre Drungche (Ganden and Drepung Monks Assembly); this body then ruled Tibet for ten years until dissolved, when a National Assembly of monks and officials called the Tsongdu was created and took over. Smith makes no mention of Shetra or Dondrup acting as usurpers and despots in this period.

In any case, Trinley Gyatso died within three years of assuming power. In 1873, at the age of 20 “he suddenly became ill and passed away”. On the cause of his early death, accounts diverge. Mullin relates an interesting theory, based on cited Tibetan sources: out of concern for the monastic tradition, Trinley Gyatso chose to die and reincarnate as the 13th Dalai Lama, rather than taking the option of marrying a woman called Rigma Tsomo from Kokonor and leaving an heir to “oversee Tibet’s future”. Shakabpa on the other hand, without citing sources, notes that Trinley Gyatso was influenced and manipulated by two close acquaintances who were subsequently accused of having a hand in his fatal illness and imprisoned, tortured and exiled as a result.

13th Dalai Lama

Throne awaiting Dalai Lama’s return. Summer residence of 14th Dalai Lama, Nechung, Tibet.

In 1877, request to exempt Lobu Zangtab Kaijia Mucuo (Chinese: 罗布藏塔布开甲木措) from using lot-drawing process Golden Urn to become the 13th Dalai Lama was approved by the Central Government. The 13th Dalai Lama assumed ruling power from the monasteries, which previously had great influence on the Regent, in 1895. Due to his two periods of exile in 1904–1909 to escape the British invasion of 1904, and from 1910–1912 to escape a Chinese invasion, he became well aware of the complexities of international politics and was the first Dalai Lama to become aware of the importance of foreign relations. After his return from exile in India and Sikkim during January 1913, he assumed control of foreign relations and dealt directly with the Maharaja, with the British Political officer in Sikkim and with the king of Nepal – rather than letting the Kashag or parliament do it.

The Great Thirteenth Thubten Gyatso then published the Tibetan Declaration of Independence for the entirety of Tibet in 1913. Tibet’s independence was never recognized by the Chinese (who claimed all land ever administered by the Manchus) but was recognized by the Kingdom of Nepal, who would use Tibet as one of its first references regarding its independent status when submitting an application to join the UN. On it, Nepal listed Tibet as a country just as independent and sovereign, with no mention of Chinese ‘suzerainty’. Its relations with Tibet were apparently second in significance only to its relations with Britain, and even more significant than its relations with the USA or even India. Furthermore, Tibet and Mongolia both signed the Treaty of friendship and alliance between the Government of Mongolia and Tibet. Neither countries’ independence statuses were ever recognized by the KMT government in China, who would continue to completely claim both as Chinese territory. He expelled the ambans and all Chinese civilians in the country and instituted many measures to modernize Tibet. These included provisions to curb excessive demands on peasants for provisions by the monasteries and tax evasion by the nobles, setting up an independent police force, the abolition of the death penalty, extension of secular education, and the provision of electricity throughout the city of Lhasa in the 1920s. He died in 1933.

14th Dalai Lama

The Dalai Lama giving teachings at Sissu, Lahaul

The 14th Dalai Lama was born on 6 July 1935 on a straw mat in a cowshed to a farmer’s family in a remote part of Tibet. According to most Western journalistic sources he was born into a humble family of farmers as one of 16 children, and one of the three reincarnated Rinpoches in the same family. On February 5, 1940, request to exempt Lhamo Thondup (Chinese: 拉木登珠) from lot-drawing process to become the 14th Dalai Lama was approved by the Central Government.

The 14th Dalai Lama became one of the two most popular world leaders by 2013 (tied with Barack Obama), according to a poll conducted by Harris Interactive of New York, which sampled public opinion in the US and six major European countries.

The 14th Dalai Lama was not formally enthroned until 17 November 1950, during the Battle of Chamdo with the People’s Republic of China. On 18 April 1959, the 14th Dalai Lama issued statement that in 1951, the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government were pressured into accepting the Seventeen Point Agreement for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet by which it became formally incorporated into the People’s Republic of China. The United States already informed the Dalai Lama in 1951 that in order to receive assistance and support from the United States, he must depart from Tibet and publicly disavow “agreements concluded under duress” between the representatives of Tibet and China. Fearing for his life in the wake of a revolt in Tibet in 1959, the 14th Dalai Lama fled to India, from where he led a government in exile.

With the aim of launching guerrilla operations against the Chinese, the Central Intelligence Agency funded the Dalai Lama’s administration with US$1.7 million a year in the 1960s. In 2001 the 14th Dalai Lama ceded his partial power over the government to an elected parliament of selected Tibetan exiles. His original goal was full independence for Tibet, but by the late 1980s he was seeking high-level autonomy instead. He continued to seek greater autonomy from China, but Dolma Gyari, deputy speaker of the parliament-in-exile, stated: “If the middle path fails in the short term, we will be forced to opt for complete independence or self-determination as per the UN charter”.

In 2014 and 2016, he stated that Tibet wants to be part of China but China should let Tibet preserve its culture and script.

In 2018, he stated that “Europe belongs to the Europeans” and that Europe has a moral obligation to aid refugees whose lives are in peril. Further he stated that Europe should receive, help and educate refugees but ultimately they should return to develop their home countries.

In March 2019, the Dalai Lama spoke out about his successor, saying that after his death he is likely to be reincarnated in India. He also warned that any Chinese interference in succession should not be considered valid.

In October 2020, he stated that he did not support Tibetan independence and hoped to visit China as a Nobel Prize winner. He said “I prefer the concept of a ‘republic’ in the People’s Republic of China. In the concept of republic, ethnic minorities are like Tibetans, The Mongols, Manchus, and Xinjiang Uyghurs, we can live in harmony”.

Residences

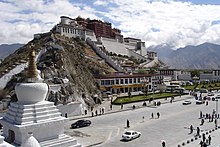

The 1st Dalai Lama was based at Tashi Lhunpo Monastery, which he founded, and the Second to the Fifth Dalai Lamas were mainly based at Drepung Monastery outside Lhasa. In 1645, after the unification of Tibet, the Fifth moved to the ruins of a royal fortress or residence on top of Marpori (‘Red Mountain’) in Lhasa and decided to build a palace on the same site. This ruined palace, called Tritse Marpo, was originally built around 636 AD by the founder of the Tibetan Empire, Songtsen Gampo for his Nepalese wife. Amongst the ruins there was just a small temple left where Tsongkhapa had given a teaching when he arrived in Lhasa in the 1380s. The Fifth Dalai Lama began construction of the Potala Palace on this site in 1645, carefully incorporating what was left of his predecessor’s palace into its structure. From then on and until today, unless on tour or in exile the Dalai Lamas have always spent their winters at the Potala Palace and their summers at the Norbulingka palace and park. Both palaces are in Lhasa and approximately 3 km apart.

Following the failed 1959 Tibetan uprising, the 14th Dalai Lama sought refuge in India. Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru allowed in the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government officials. The Dalai Lama has since lived in exile in McLeod Ganj, in the Kangra district of Himachal Pradesh in northern India, where the Central Tibetan Administration is also established. His residence on the Temple Road in McLeod Ganj is called the Dalai Lama Temple and is visited by people from across the globe. Tibetan refugees have constructed and opened many schools and Buddhist temples in Dharamshala.

-

Potala Palace

-

Norbulingka

Searching for the reincarnation

The search for the 14th Dalai Lama took the High Lamas to Taktser in Amdo

Palden Lhamo, the female guardian spirit of the sacred lake, Lhamo La-tso, who promised Gendun Drup the 1st Dalai Lama in one of his visions that “she would protect the ‘reincarnation’ lineage of the Dalai Lamas”

By the Himalayan tradition, phowa is the discipline that is believed to transfer the mindstream to the intended body. Upon the death of the Dalai Lama and consultation with the Nechung Oracle, a search for the Lama’s yangsi, or reincarnation, is conducted. The government of the People’s Republic of China has stated its intention to be the ultimate authority on the selection of the next Dalai Lama.

High Lamas may also claim to have a vision by a dream or if the Dalai Lama was cremated, they will often monitor the direction of the smoke as an ‘indication’ of the direction of the expected rebirth.

If there is only one boy found, the High Lamas will invite Living Buddhas of the three great monasteries, together with secular clergy and monk officials, to ‘confirm their findings’ and then report to the Central Government through the Minister of Tibet. Later, a group consisting of the three major servants of Dalai Lama, eminent officials, and troops will collect the boy and his family and travel to Lhasa, where the boy would be taken, usually to Drepung Monastery, to study the Buddhist sutra in preparation for assuming the role of spiritual leader of Tibet.

If there are several possible claimed reincarnations, however, regents, eminent officials, monks at the Jokhang in Lhasa, and the Minister to Tibet have historically decided on the individual by putting the boys’ names inside an urn and drawing one lot in public if it was too difficult to judge the reincarnation initially.

In his autobiography, Freedom in Exile, the Dalai Lama states that after he dies it is possible that his people will no longer want a Dalai Lama, in which case there would be no search for the Lama’s reincarnation. “So, I might take rebirth as an insect, or an animal – whatever would be of most value to the largest number of sentient beings” (p.237).

List of Dalai Lamas

There have been 14 recognised incarnations of the Dalai Lama:

| Name | Picture | Lifespan | Recognised | Enthronement | Tibetan/Wylie | Tibetan pinyin/Chinese | Alternative spellings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gendun Drup |  |

1391–1474 | – | N/A | དགེ་འདུན་འགྲུབ་ dge ‘dun ‘grub |

Gêdün Chub 根敦朱巴 |

Gedun Drub Gedün Drup |

| 2 | Gendun Gyatso |  |

1475–1542 | 1483 | 1487 | དགེ་འདུན་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ dge ‘dun rgya mtsho |

Gêdün Gyaco 根敦嘉措 |

Gedün Gyatso Gendün Gyatso |

| 3 | Sonam Gyatso |  |

1543–1588 | 1546 | 1578 | བསོད་ནམས་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ bsod nams rgya mtsho |

Soinam Gyaco 索南嘉措 |

Sönam Gyatso |

| 4 | Yonten Gyatso |  |

1589–1617 | 1601 | 1603 | ཡོན་ཏན་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ yon tan rgya mtsho |

Yoindain Gyaco 雲丹嘉措 |

Yontan Gyatso, Yönden Gyatso |

| 5 | Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso |  |

1617–1682 | 1618 | 1622 | བློ་བཟང་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ blo bzang rgya mtsho |

Lobsang Gyaco 羅桑嘉措 |

Lobzang Gyatso Lopsang Gyatso |

| 6 | Tsangyang Gyatso |  |

1683–1706 | 1688 | 1697 | ཚངས་དབྱངས་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ tshang dbyangs rgya mtsho |

Cangyang Gyaco 倉央嘉措 |

Tsañyang Gyatso |

| 7 | Kelzang Gyatso |  |

1707–1757 | 1712 | 1720 | བསྐལ་བཟང་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ bskal bzang rgya mtsho |

Gaisang Gyaco 格桑嘉措 |

Kelsang Gyatso Kalsang Gyatso |

| 8 | Jamphel Gyatso |  |

1758–1804 | 1760 | 1762 | བྱམས་སྤེལ་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ byams spel rgya mtsho |

Qambê Gyaco 強白嘉措 |

Jampel Gyatso Jampal Gyatso |

| 9 | Lungtok Gyatso |  |

1805–1815 | 1807 | 1808 | ལུང་རྟོགས་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ lung rtogs rgya mtsho |

Lungdog Gyaco 隆朵嘉措 |

Lungtog Gyatso |

| 10 | Tsultrim Gyatso | 1816–1837 | 1822 | 1822 | ཚུལ་ཁྲིམས་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ tshul khrim rgya mtsho |

Cüchim Gyaco 楚臣嘉措 |

Tshültrim Gyatso | |

| 11 | Khendrup Gyatso |  |

1838–1856 | 1841 | 1842 | མཁས་གྲུབ་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ mkhas grub rgya mtsho |

Kaichub Gyaco 凱珠嘉措 |

Kedrub Gyatso |

| 12 | Trinley Gyatso |  |

1857–1875 | 1858 | 1860 | འཕྲིན་ལས་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ ‘phrin las rgya mtsho |

Chinlai Gyaco 成烈嘉措 |

Trinle Gyatso |

| 13 | Thubten Gyatso |  |

1876–1933 | 1878 | 1879 | ཐུབ་བསྟན་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ thub bstan rgya mtsho |

Tubdain Gyaco 土登嘉措 |

Thubtan Gyatso Thupten Gyatso |

| 14 | Tenzin Gyatso |  |

born 1935 | 1939[267] | 1940 (currently in exile) |

བསྟན་འཛིན་རྒྱ་མཚོ་ bstan ‘dzin rgya mtsho |

Dainzin Gyaco 丹增嘉措 |

Tenzin Gyatso |

There has also been one non-recognised Dalai Lama, Ngawang Yeshe Gyatso, declared 28 June 1707, when he was 25 years old, by Lha-bzang Khan as the “true” 6th Dalai Lama – however, he was never accepted as such by the majority of the population.

Future of the position

The main teaching room of the Dalai Lama in Dharamshala, India

14th Dalai Lama

In the mid-1970s, Tenzin Gyatso told a Polish newspaper that he thought he would be the last Dalai Lama. In a later interview published in the English language press he stated, “The Dalai Lama office was an institution created to benefit others. It is possible that it will soon have outlived its usefulness.” These statements caused a furore amongst Tibetans in India. Many could not believe that such an option could even be considered. It was further felt that it was not the Dalai Lama’s decision to reincarnate. Rather, they felt that since the Dalai Lama is a national institution it was up to the people of Tibet to decide whether the Dalai Lama should reincarnate.

The government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has claimed the power to approve the naming of “high” reincarnations in Tibet, based on a precedent set by the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing dynasty. The Qianlong Emperor instituted a system of selecting the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama by a lottery that used a Golden Urn with names wrapped in clumps of barley. This method was used a few times for both positions during the 19th century, but eventually fell into disuse. In 1995, the Dalai Lama chose to proceed with the selection of the 11th reincarnation of the Panchen Lama without the use of the Golden Urn, while the Chinese government insisted that it must be used. This has led to two rival Panchen Lamas: Gyaincain Norbu as chosen by the Chinese government’s process, and Gedhun Choekyi Nyima as chosen by the Dalai Lama. However, Nyima was abducted by the Chinese government shortly after being chosen as the Panchen Lama and has not been seen in public since 1995.

In September 2007, the Chinese government said all high monks must be approved by the government, which would include the selection of the 15th Dalai Lama after the death of Tenzin Gyatso. Since by tradition, the Panchen Lama must approve the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama, that is another possible method of control. Consequently, the Dalai Lama has alluded to the possibility of a referendum to determine the 15th Dalai Lama.

In response to this scenario, Tashi Wangdi, the representative of the 14th Dalai Lama, replied that the Chinese government’s selection would be meaningless. “You can’t impose an Imam, an Archbishop, saints, any religion…you can’t politically impose these things on people”, said Wangdi. “It has to be a decision of the followers of that tradition. The Chinese can use their political power: force. Again, it’s meaningless. Like their Panchen Lama. And they can’t keep their Panchen Lama in Tibet. They tried to bring him to his monastery many times but people would not see him. How can you have a religious leader like that?”

The 14th Dalai Lama said as early as 1969 that it was for the Tibetans to decide whether the institution of the Dalai Lama “should continue or not”. He has given reference to a possible vote occurring in the future for all Tibetan Buddhists to decide whether they wish to recognize his rebirth. In response to the possibility that the PRC might attempt to choose his successor, the Dalai Lama said he would not be reborn in a country controlled by the People’s Republic of China or any other country which is not free. According to Robert D. Kaplan, this could mean that “the next Dalai Lama might come from the Tibetan cultural belt that stretches across Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh, Nepal, and Bhutan, presumably making him even more pro-Indian and hence anti-Chinese”.

The 14th Dalai Lama supported the possibility that his next incarnation could be a woman. As an “engaged Buddhist” the Dalai Lama has an appeal straddling cultures and political systems making him one of the most recognized and respected moral voices today. “Despite the complex historical, religious and political factors surrounding the selection of incarnate masters in the exiled Tibetan tradition, the Dalai Lama is open to change”, author Michaela Haas writes.