The Timurid Empire (Persian: تیموریان), self-designated as Gurkani (Persian: گورکانیان), was a Persianate Turco-Mongol empire comprising modern-day Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Iran, the southern region of the Caucasus, Mesopotamia, Afghanistan, much of Central Asia, as well as parts of contemporary India, Pakistan, Syria, and Turkey.

The empire was founded by Timur (also known as Tamerlane), a warlord of Turco-Mongol lineage, who established the empire between 1370 and his death in 1405. He envisioned himself as the great restorer of the Mongol Empire of Genghis Khan, regarded himself as Genghis’s heir, and associated much with the Borjigin. Timur continued vigorous trade relations with Ming China and the Golden Horde. The empire led to the Timurid Renaissance, particularly during the reign of astronomer and mathematician Ulugh Begh.

In 1467, the ruling Timurid dynasty, or Timurids, lost most of Persia to the Aq Qoyunlu confederation. But members of the Timurid dynasty continued to rule smaller states, sometimes known as Timurid emirates, in Central Asia and parts of India. In the 16th century, Babur, a Timurid prince from Ferghana (modern Uzbekistan), invaded Kabulistan (modern Afghanistan) and established a small kingdom there. Twenty years later, he used this kingdom as a staging ground to invade India and establish the Mughal Empire.

History

|

| History of Greater Iran |

|---|

Timur conquered large parts of ancient great Persian territories in Central Asia, primarily Transoxiana and Khorasan, from 1363 onwards with various alliances (Samarkand in 1366, and Balkh in 1369), and was recognized as ruler over them in 1370. Acting officially in the name of Suurgatmish, the Chagatai khan, he subjugated Transoxania and Khwarazm in the years that followed. Already in the 1360s he had gained control of the western Chagatai Khanate and while as emir he was nominally subordinate to the khan, in reality it was now Timur that picked the khans who became mere puppet rulers. The western Chagatai khans were continually dominated by Timurid princes in the 15th and 16th centuries and their figurehead importance was eventually reduced into total insignificance.

Rise

Timur began a campaign westwards in 1380, invading the various successor states of the Ilkhanate. By 1389, he had removed the Kartids from Herat and advanced into mainland Persia where he enjoyed many successes. This included the capture of Isfahan in 1387, the removal of the Muzaffarids from Shiraz in 1393, and the expulsion of the Jalayirids from Baghdad. In 1394–95, he triumphed over the Golden Horde, following his successful campaign in Georgia, after which he enforced his sovereignty in the Caucasus. Tokhtamysh, the khan of the Golden Horde, was a major rival to Timur in the region. He also subjugated Multan and Dipalpur in modern-day Pakistan in 1398. Timur gave the north Indian territories to a non-family member, Khizr Khan, whose Sayyid dynasty replaced the defeated Tughlaq dynasty of the Sultanate of Delhi. Delhi became a vassal of the Timurids but obtained independence in the years following the death of Timur. In 1400–1401 he conquered Aleppo, Damascus and eastern Anatolia, in 1401 he destroyed Baghdad and in 1402 defeated the Ottomans in the Battle of Ankara. This made Timur the most preeminent Muslim ruler of the time, as the Ottoman Empire plunged into civil war. Meanwhile, he transformed Samarkand into a major capital and seat of his realm.

Stagnation and decline

Timur appointed his sons and grandsons to the main governorships of the different parts of his empire, and outsiders to some others. After his death in 1405, the family quickly fell into disputes and civil wars, and many of the governorships became effectively independent. However, Timurid rulers continued to dominate Persia, Mesopotamia, Armenia, large parts of Azerbaijan, Afghanistan, Pakistan,minor parts of India, and much of Central Asia, though the Anatolian and Caucasian territories were lost by the 1430s to the Qara Qoyunlu. Due to the fact that the Persian cities were desolated by wars, the seat of Persian culture was now in Samarkand and Herat, cities that became the center of the Timurid renaissance. The cost of Timur’s conquests amount to the deaths of possibly 17 million people.

Shahrukh Mirza, fourth ruler of the Timurids, dealt with Kara Koyunlu, who aimed to expand into Iran. But, Jahan Shah (bey of the Kara Koyunlu) drove the Timurids to eastern Iran after 1447 and also briefly occupied Herat in 1458. After the death of Jahan Shah, Uzun Hasan, bey of the Aq Qoyunlu, conquered the holdings of the Kara Qoyunlu in Iran between 1469 and 1471.

Fall

The power of Timurids declined rapidly during the second half of the 15th century, largely due to the Timurid tradition of partitioning the empire. The Aq Qoyunluconquered most of Iran from the Timurids, and by 1500, the divided and wartorn Timurid Empire had lost control of most of its territory, and in the following years was effectively pushed back on all fronts. Persia, the Caucasus, Mesopotamia, and Eastern Anatolia fell quickly to the Shiite Safavid Empire, secured by Shah Ismail I in the following decade. Much of the Central Asian lands was overrun by the Uzbeks of Muhammad Shaybani who conquered the key cities of Samarkand and Herat in 1505 and 1507, and who founded the Khanate of Bukhara. From Kabul, the Mughal Empirewas established in 1526 by Babur, a descendant of Timur through his father and possibly a descendant of Genghis Khan through his mother. The dynasty he established is commonly known as the Mughal dynasty though it was directly inherited from the Timurids. By the 17th century, the Mughal Empire ruled most of India but eventually declined during the following century. The Timurid dynasty finally came to an end as the remaining nominal rule of the Mughals was abolished by the British Empirefollowing the 1857 rebellion.

Culture

Timur – Forensic facial reconstruction by M. Gerasimov, 1941

Although the Timurids hailed from the Barlastribe, which was of Turkicized Mongol origin, they had embraced Persian culture, converted to Islam, and resided in Turkestan and Khorasan. Thus, the Timurid era had a dual character, reflecting both its Turco-Mongol origins and the Persian literary, artistic, and courtly high culture of the dynasty.

Language

During the Timurid era, Central Asian society was bifurcated, with the responsibilities of government and rule divided into military and civilian spheres along ethnic lines. At least in the early stages, the military was almost exclusively Turko-Mongolian, while the civilian and administrative element was almost exclusively Persian. The spoken language shared by all the Turko-Mongolians throughout the area was Chaghatay. The political organization hearkened back to the steppe-nomadic system of patronage introduced by Genghis Khan. The major language of the period, however, was Persian, the native language of the Tājīk(Persian) component of society and the language of learning acquired by all literate or urban people. Timur was already steeped in Persian culture and in most of the territories he incorporated, Persian was the primary language of administration and literary culture. Thus the language of the settled “diwan” was Persian, and its scribes had to be thoroughly adept in Persian culture, whatever their ethnic origin. Persian became the official state language of the Timurid Empire and served as the language of administration, history, belles lettres, and poetry. The Chaghatay language was the native and “home language” of the Timurid family, while Arabic served as the language par excellence of science, philosophy, theology and the religious sciences.

Literature

Persian

Folio of Poetry From the Divan of Sultan Husayn Mirza, c. 1490. Brooklyn Museum.

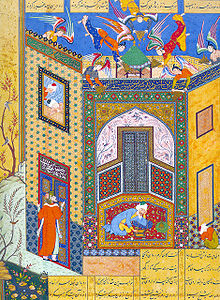

Illustration from Jāmī’s Rose Garden of the Pious, dated 1553. The image blends Persian poetry and Persian miniature into one, as is the norm for many works of the Timurid era.

Persian literature, especially Persian poetry, occupied a central place in the process of assimilation of the Timurid elite to the Perso-Islamic courtly culture. The Timurid sultans, especially Shāh Rukh Mīrzā and his son Mohammad Taragai Oloğ Beg, patronized Persian culture. Among the most important literary works of the Timurid era is the Persian biography of Timur, known as Zafarnāmeh(Persian: ظفرنامه), written by Sharaf al-Din Ali Yazdi, which itself is based on an older Zafarnāmeh by Nizām al-Dīn Shāmī, the official biographer of Timur during his lifetime. The most famous poet of the Timurid era was Nūr ud-Dīn Jāmī, the last great medieval Sufimystic of Persia and one of the greatest in Persian poetry. In addition, some of the astronomical works of the Timurid sultan Ulugh Beg were written in Persian, although the bulk of it was published in Arabic. The Timurid prince Baysunghur also commissioned a new edition of the Persian national epic Shāhnāmeh, known as Shāhnāmeh of Baysunghur, and wrote an introduction to it. According to T. Lenz:

It can be viewed as a specific reaction in the wake of Timur’s death in 807/1405 to the new cultural demands facing Shahhrokh and his sons, a Turkic military elite no longer deriving their power and influence solely from a charismatic steppe leader with a carefully cultivated linkage to Mongol aristocracy. Now centered in Khorasan, the ruling house regarded the increased assimilation and patronage of Persian culture as an integral component of efforts to secure the legitimacy and authority of the dynasty within the context of the Islamic Iranian monarchical tradition, and the Baysanghur Shahnameh, as much a precious object as it is a manuscript to be read, powerfully symbolizes the Timurid conception of their own place in that tradition. A valuable documentary source for Timurid decorative arts that have all but disappeared for the period, the manuscript still awaits a comprehensive monographic study.

Chagatai

The Timurids also played a very important role in the history of Turkic literature. Based on the established Persian literary tradition, a national Turkic literature was developed in the Chagatai language. Chagatai poets such as Mīr Alī Sher Nawā’ī, Sultan Husayn Bāyqarā, and Zāhiruddīn Bābur encouraged other Turkic-speaking poets to write in their own vernacular in addition to Arabic and Persian. The Bāburnāma, the autobiography of Bābur (although being highly Persianized in its sentence structure, morphology, and vocabulary), as well as Mīr Alī Sher Nawā’ī’s Chagatai poetry are among the best-known Turkic literary works and have influenced many others.

Art

The golden age of Persian painting began during the reign of the Timurids. During this period – and analogous to the developments in Safavid Persia – Chinese art and artists had a significant influence on Persian art. Timurid artists refined the Persian art of the book, which combines paper, calligraphy, illumination, illustration and binding in a brilliant and colourful whole. The Mongol ethnicity of the Chaghatayid and Timurid Khans was the source of the stylistic depiction of Persian art during the Middle Ages. These same Mongols intermarried with the Persians and Turks of Central Asia, even adopting their religion and languages. Yet their simple control of the world at that time, particularly in the 13th–15th centuries, reflected itself in the idealised appearance of Persians as Mongols. Though the ethnic make-up gradually blended into the Iranianand Mesopotamian local populations, the Mongol stylism continued well after and crossed into Asia Minor and even North Africa.

Timurid architecture

Timurid architecture drew on and developed many Seljuq traditions. Turquoise and blue tiles forming intricate linear and geometric patterns decorated the facades of buildings. Sometimes the interior was decorated similarly, with painting and stuccorelief further enriching the effect. Timurid architecture is the pinnacle of Islamic art in Central Asia. Spectacular and stately edifices erected by Timur and his successors in Samarkand and Herat helped to disseminate the influence of the Ilkhanid school of art in India, thus giving rise to the celebrated Mughal (or Mongol) school of architecture. Timurid architecture started with the sanctuary of Ahmed Yasawi in present-day Kazakhstan and culminated in Timur’s mausoleum Gur-e Amir in Samarkand. Timur’s Gur-I Mir, the 14th-century mausoleum of the conqueror is covered with “turquoise Persian tiles”. Nearby, in the center of the ancient town, a “Persian style madrassa” (religious school) and a “Persian style mosque” by Ulugh Beg is observed. The mausoleum of Timurid princes, with their turquoise and blue-tiled domes remain among the most refined and exquisite Persian architecture. Axial symmetry is a characteristic of all major Timurid structures, notably the Shāh-e Zenda in Samarkand, the Musallah complex in Herat, and the mosque of Gawhar Shad in Mashhad. Double domes of various shapes abound, and the outsides are perfused with brilliant colors. Timur’s dominance of the region strengthened the influence of his capital and Persian architecture upon India.

-

Akhangan’s tomb, where Gawhar Shad’s sister Gowhartāj is buried. The architecture is a fine example of the Timurid era in Persia.

-

Façade of Bibi Khanym Mosque.

Military

In the Chagatay translation of Ali Yazdi’s Zafarnama, Timur’s army is called “Chagatay army” (Čaġatāy čerigi).

The Timurids relied on conscription of troops from settled populations. They were unable to fully subjugate many other nomadic tribes. This was not because of lack of military power as Timur succeeded in defeating them, but rather that he was unwilling to integrate autonomous tribes into his power structure due to his centralised governance. The tribes were too mobile to effectively suppress and the loss of their autonomy was unattractive to them. Hence, Timur was unable to win the loyalty of the tribes and his hold over them did not survive his death.

The role of slave soldiers such as the ghilman and mamluks was considerably smaller in Mongol-based armies like the Timurids, as compared to other Islamic societies.

The Timurids had a contingent called the nambardar levy, which mostly consisted of native Iranians, and occasionally scholars and fiscal administrators. The nambardar were used to bolster the size of the army for large expeditions.

Rulers

Emperors (Emir)

- Timur

- Pir Muhammad (son of Jahangir) (ruled 1405–1407)

- Khalil Sultan

- Shah Rukh

- Ulugh Beg

- Abdal-Latif Mirza

- Abdullah Mirza

- Sultan Muhammad

- Abul-Qasim Babur Mirza

- Sultan Ahmed Mirza

- Sultan Mahmud Mirza

- Mirza Shah Mahmud

- Ibrahim Mirza

- Abu Sa’id Mirza

- Sultan Husayn Bayqara

- Yadgar Muhammad Mirza (ruled 1469–1470)

- Badi’ al-Zaman Mirza

Governors Mirza

|

|

This section does not cite any sources. (July 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

- Qaidu bin Pir Muhammad bin Jahāngīr 808–811 AH

- Abu Bakr bin Mīrān Shāh 1405–1407 (807–809 AH)

- Pir Muhammad (son of Umar Shaikh) 807–812 AH

- Rustam 812–817 AH

- Sikandar 812–817 AH

- Ala al-Dawla Mirza 851 AH

- Abu Bakr bin Muhammad 851 AH

- Sultān Muhammad 850–855 AH

- Muhammad bin Hussayn 903–906 AH

- Abul A’la Fereydūn Hussayn 911–912 AH

- Muhammad Mohsin Khān 911–912 AH

- Muhammad Zamān Khān 920–923 AH

- Shāhrukh II bin Abu Sa’id 896–897 AH

- Ulugh Beg II 873–907 AH

- Sultān Uways 1508–1522 (913–927 AH)