The Turkic peoples are a collection of ethnic groups of Central, East, North and West Asia as well as parts of Europe and North Africa, who speak Turkic languages.

The origins of the Turkic peoples has been a topic of much discussion. Recent linguistic, genetic and archaeological evidence suggests that the earliest Turkic peoples descended from agricultural communities in Northeast China who moved westwards into Mongolia in the late 3rd millennium BC, where they adopted a pastoral lifestyle. By the early 1st millennium BC, these peoples had become equestrian nomads. In subsequent centuries, the steppe populations of Central Asia appear to have been progressively Turkified by a heterogenous East Asian dominant minority moving out of Mongolia. Many vastly differing ethnic groups have throughout history become part of the Turkic peoples through language shift, acculturation, conquest, intermixing, adoption and religious conversion. Nevertheless, certain Turkic peoples share, to varying degrees, non-linguistic characteristics like cultural traits, ancestry from a common gene pool, and historical experiences.

The most notable modern Turkic-speaking ethnic groups include Turkish people, Azerbaijanis, Uzbeks, Kazakhs, Turkmens, Kyrgyz and Uyghur people.

Etymology

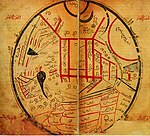

Map from Kashgari’s Diwan (11th century), showing the distribution of Turkic tribes.

The first known mention of the term Turk (Old Turkic: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰 Türük or 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰:𐰜𐰇𐰛 Kök Türük, Chinese: 突厥, Pinyin: Tūjué < Middle Chinese *tɦut-kyat< *dwət-kuɑt, Old Tibetan: drugu) applied to only one Turkic group, namely, the Göktürks, who were also mentioned, as türüg ~ török, in the 6th-century Khüis Tolgoi inscription, most likely not later than 587 AD. A letter by Ishbara Qaghan to Emperor Wen of Sui in 585 described him as “the Great Turk Khan”. The Bugut (584 CE) and Orkhon inscriptions (735 CE) use the terms Türküt, Türk and Türük.

Previous use of similar terms are of unknown significance, although some strongly feel that they are evidence of the historical continuity of the term and the people as a linguistic unit since early times. This includes the Chinese Spring and Autumn Annals, which refer to a neighbouring people as Beidi.During the first century CE, Pomponius Mela refers to the Turcae in the forests north of the Sea of Azov, and Pliny the Elder lists the Tyrcae among the people of the same area. However, English archaeologist Ellis Minns contended that Tyrcae Τῦρκαι is “a false correction” for Iyrcae Ἱύρκαι, a people who dwelt beyond the Thyssagetae, according to Herodotus (Histories, iv. 22), and were likely Ugric ancestors of Magyars. There are references to certain groups in antiquity whose names might have been foreign transcriptions of Tür(ü)k such as Togarma, Turukha/Turuška, Turukkuand so on; but the information gap is so substantial that any connection of these ancient people to the modern Turks is not possible.

It is generally accepted that the name Türk is ultimately derived from the Old-Turkic migration-term 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰 Türük/Törük, which means ‘created, born’ or ‘strong’, from the Old Turkic word root *türi-/töri- ‘tribal root, (mythic) ancestry; take shape, to be born, be created, arise, spring up’ and derived with the Old Turkic suffix 𐰰 (-ik), perhaps from Proto-Turkic *türi-k ‘lineage, ancestry’, (compare also the Proto-Turkic word root *töre- to be born, originate’). Scholars, including Toru Haneda, Onogawa Hidemi, and Geng Shimin believed that Di, Dili, Dingling, Chile and Tujue all came from the Turkic word Türk, which means ‘powerful’ and ‘strength’, and its plural form is Türküt. Even though Gerhard Doerfer supports the proposal that türk means ‘strong’ in general, Gerard Clauson points out that “the word türk is never used in the generalized sense of ‘strong'” and that türk was originally a noun and meant “‘the culminating point of maturity’ (of a fruit, human being, etc.), but more often used as an meaning (of a fruit) ‘just fully ripe’; (of a human being) ‘in the prime of life, young, and vigorous'”. Turkologist Peter B. Golden agrees that the term Turk has roots in Old Turkic. yet is not convinced by attempts to link Dili, Dingling, Chile, Tele, & Tiele, which possibly transcribed *tegrek (probably meaning ‘cart’), to Tujue, which transliterated Türküt. The Chinese Book of Zhou (7th century) presents an etymology of the name Turk as derived from ‘helmet’, explaining that this name comes from the shape of a mountain where they worked in the Altai Mountains.Hungarian scholar András Róna-Tas (1991) pointed to a Khotanese-Saka word, tturakä ‘lid’, semantically stretchable to ‘helmet’, as a possible source for this folk etymology, yet Golden thinks this connection requires more data.

The earliest Turkic-speaking peoples identifiable in Chinese sources are the Gekun and Xinli, located in South Siberia. Another earlier people, the Dingling, are often also assumed to be Proto-Turks, or are alternatively linked to Tungusic peoples or Na-Dené and Yeniseian peoples. Medieval European chroniclers subsumed various Turkic peoples of the Eurasian steppe under the “umbrella-identity” of the “Scythians”. Between 400 CE and the 16th century, Byzantine sources use the name Σκύθαι (Skuthai) in reference to twelve different Turkic peoples.

In the modern Turkish language as used in the Republic of Turkey, a distinction is made between “Turks” and the “Turkic peoples” in loosely speaking: the term Türk corresponds specifically to the “Turkish-speaking” people (in this context, “Turkish-speaking” is considered the same as “Turkic-speaking”), while the term Türki refers generally to the people of modern “Turkic Republics” (Türki Cumhuriyetler or Türk Cumhuriyetleri). However, the proper usage of the term is based on the linguistic classification in order to avoid any politicalsense. In short, the term Türki can be used for Türk or vice versa.

List of ethnic groups

| List of the modern Turkic peoples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnonym | Population | National-state formation | Religion | |

| Turkish | 75,700,000 | Sunni Islam, Alevism | ||

| Azerbaijanis | 31,300,000 | Shia Islam, Sunni Islam | ||

| Uzbeks | 30,700,000 | Sunni Islam | ||

| Kazakhs | 15,100,000 | Sunni Islam | ||

| Uyghurs | 11,900,000 | Sunni Islam | ||

| Turkmens | 8,000,000 | Sunni Islam | ||

| Tatars | 6,200,000 | Sunni Islam, Orthodox Christianity | ||

| Kyrgyz | 6,000,000 | Sunni Islam | ||

| Bashkirs | 1,700,000 | Sunni Islam | ||

| Chuvashes | 1,500,000 | Orthodox Christianity, Vattisen Yaly | ||

| Khorasani Turks | 1,000,000 | No | Shia Islam | |

| Qashqai | 949,000 | No | Shia Islam | |

| Karakalpaks | 796,000 | Sunni Islam | ||

| Kumyks | 520,000 | Sunni Islam | ||

| Crimean Tatars | from 500,000 | Sunni Islam | ||

| Yakuts(Sakha) | 482,000 | Orthodox Christianity, Tengrism | ||

| Karachays | 346,000 | Sunni Islam | ||

| Tuvans | 273,000 | Tibetan Buddhism, Tengrism | ||

| Gagauz | 126,000 | Orthodox Christianity | ||

| Balkars | 112,000 | Sunni Islam | ||

| Nogais | 110,000 | Sunni Islam | ||

| Salar | 104,000 | Sunni Islam, Tibetan Buddhism | ||

| Khakas | 75,000 | Orthodox Christianity, Tengrism | ||

| Altaians | 70,000 | Burkhanism, Tengrism, Orthodox Christianity | ||

| Khalaj | 42,000 | No | Shia Islam | |

| Yugurs | 13,000 | Tibetan Buddhism, Tengrism | ||

| Dolgans | 13,000 | Tengrism, Orthodox Christianity | ||

| Khotons | 10,000 | No | Sunni Islam | |

| Shors | 8,000 | No | Orthodox Christianity, Tengrism | |

| Siberian Tatars | 6,000 | No | Sunni Islam | |

| Crimean Karaites | 2,000 | No | Karaite Judaism | |

| Krymchaks | 1,000 | No | Orthodox Judaism | |

| Tofalars | 800 | No | Tengrism, Orthodox Christianity | |

| Chulyms | 355 | No | Orthodox Christianity | |

| Dukha | 282 | No | Tengrism | |

- Historical Turkic groups

- Az

- Dingling

- Bulgars

- Alat

- Basmyl

- Onogurs

- Saragurs

- Sabirs

- Shatuo

- Yueban

- Göktürks

- Oghuz Turks

- Kankalis

- Khazars

- Kipchaks

- Kumans

- Karluks

- Tiele

- Turgesh

- Yenisei Kirghiz

- Chigils

- Toquz Oghuz

- Yagma

- Nushibi

- Kutrigurs

- Duolu

- Yabaku

- Bulaqs

- Xueyantuo

- Chorni Klobuky

- Berendei

- Naimans (partly)

- Keraites (partly)

- Merkits (partly)

Possible Proto-Turkic ancestry, at least partial, has been posited for Xiongnu, Huns and Pannonian Avars, as well as Tuoba and Rouran (later Tatars), who were of Proto-Mongolic Donghu ancestry.

Notes

- ^ Even though Chinese historians routinely ascribed Xiongnu origin to various nomadic peoples, such ascriptions do not necessarily indicate the subjects’ exact origins; for examples, Xiongnu ancestry was ascribed to Turkic-speaking Göktürks and Tiele as well as Para-Mongolic-speaking Kumo Xi and Khitan.

Language

A page from “Codex Kumanicus”. The Codex was designed in order to help Catholicmissionaries communicate with the Kumans.

Distribution

The Turkic languages constitute a language family of some 30 languages, spoken across a vast area from Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean, to Siberia and Western China, and through to the Middle East. Some 170 million people have a Turkic language as their native language; an additional 20 million people speak a Turkic language as a second language. The Turkic language with the greatest number of speakers is Turkish proper, or Anatolian Turkish, the speakers of which account for about 40% of all Turkic speakers. More than one third of these are ethnic Turks of Turkey, dwelling predominantly in Turkey proper and formerly Ottoman-dominated areas of Southern and Eastern Europe and West Asia; as well as in Western Europe, Australia and the Americas as a result of immigration. The remainder of the Turkic people are concentrated in Central Asia, Russia, the Caucasus, China, and northern Iraq.

Alphabet

The Turkic alphabets are sets of related alphabets with letters (formerly known as runes), used for writing mostly Turkic languages. Inscriptions in Turkic alphabets were found in Mongolia. Most of the preserved inscriptions were dated to between 8th and 10th centuries CE.

The earliest positively dated and read Turkic inscriptions date from c. 150, and the alphabets were generally replaced by the Old Uyghur alphabet in the Central Asia, Arabic script in the Middle and Western Asia, Cyrillic in Eastern Europe and in the Balkans, and Latin alphabet in Central Europe. The latest recorded use of Turkic alphabet was recorded in Central Europe’s Hungary in 1699 CE.

The Turkic runiform scripts, unlike other typologically close scripts of the world, do not have a uniform palaeography as, for example, have the Gothic runes, noted for the exceptional uniformity of its language and paleography. The Turkic alphabets are divided into four groups, the best known of them is the Orkhon version of the Enisei group. The Orkhon script is the alphabet used by the Göktürks from the 8th century to record the Old Turkic language. It was later used by the Uyghur Empire; a Yenisei variant is known from 9th-century Kyrgyz inscriptions, and it has likely cousins in the Talas Valley of Turkestan and the Old Hungarian script of the 10th century. Irk Bitig is the only known complete manuscript text written in the Old Turkic script.

The Turkic language family is traditionally considered to be part of the proposed Altaic language family.

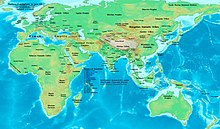

Descriptive map of Turkic peoples.

Countries and autonomous subdivisions where a Turkic language has official status or is spoken by a majority.

History

| History of the Turkic peoplespre–14th century |

|---|

|

| Tiele people |

| Göktürks |

(Tokhara Yabghus, Turk Shahis)

|

| Khazar Khaganate 618–1048 |

| Xueyantuo 628–646 |

| Kangar union 659–750 |

| Turk Shahi 665-850 |

| Türgesh Khaganate 699–766 |

| Kimek confederation 743–1035 |

| Uyghur Khaganate 744–840 |

| Oghuz Yabgu State 750–1055 |

| Karluk Yabgu State 756–940 |

| Kara-Khanid Khanate 840–1212 |

|

| Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom 848–1036 |

| Qocho 856–1335 |

| Pecheneg Khanates 860–1091 |

| Ghaznavid Empire 963–1186 |

| Seljuk Empire 1037–1194 |

|

| Cuman–Kipchak confederation 1067–1239 |

| Khwarazmian Empire 1077–1231 |

| Kerait Khanate 11th century–13th century |

| Delhi Sultanate 1206–1526 |

|

| Qarlughid Kingdom 1224–1266 |

| Golden Horde 1240s–1502 |

| Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo) 1250–1517 |

|

Eastern Hemisphere in 500 BCE

Origins

The origins of the Turkic peoples has historically been disputed, with many theories having been proposed. Peter Benjamin Goldenlisted Proto-Turkic lexical items about the climate, topography, flora, fauna, people’s modes of subsistence in the hypothetical Proto-Turkic Urheimat and proposed that the Proto-Turkic Urheimat was located at the southern, taiga-steppe zone of the Sayan-Altayregion. Martine Robbeets suggests that the Turkic peoples were descended from a Transeurasian agricultural community based in northeast China, which is to be associated with the Xinglongwa culture and the succeeding Hongshan culture. The East Asian agricultural origin of the Turkic peoples has been corroborated in multiple recent studies. Around 2,200 BC, due to the desertification of northeast China, the agricultural ancestors of the Turkic peoples probably migrated westwards into Mongolia, where they adopted a pastoral lifestyle.

Linguistic and genetic evidence strongly suggest an early presence of Turkic peoples in Mongolia. Genetic studies have shown that the early Turkic peoples were of diverse origins, and that Turkic culture was spread westwards through language diffusion rather than migrations of a homogenous population. The genetic evidence suggests that the Turkification of Central Asia was carried out by East Asian dominant minorities migrating out of Mongolia.

Early historical attestation

Xiongnu, Mongolic, and proto-Turkic tribes (ca. 300 CE)

Early Turkic speakers, such as the Tiele (also known as Gaoche 高車, lit. “High Carts”), may be related to Xiongnu and Dingling. According to the Book of Wei, the Tiele people were the remnants of the Chidi (赤狄), the red Di people competing with the Jin in the Spring and Autumn period. Historically they were established after the 6th century BCE.

Historical Arab and Persian descriptions of Turks state that they looked strange from their perspective and were extremely physically different from Arabs. Turks were described as “broad faced people with small eyes”. Medieval Muslim writers noted that Tibetansand Turks resembled each other, and that they often were not able to tell the difference between Turks and Tibetans. Moreover, on Western Turkic coins “the faces of the governor and governess are clearly mongoloid (a roundish face, narrow eyes), and the portrait have definite old Türk features (long hair, absence of headdress of the governor, a tricorn headdress of the governess)”.

Xiongnu (3rd c. BCE – 1st c. CE)

Territory of the Xiongnu, which included Mongolia, Western Manchuria, Xinjiang, East Kazakhstan, East Kyrgyzstan, Inner Mongolia, and Gansu.

The earliest separate Turkic peoples, such as the Gekun (鬲昆) and Xinli (薪犁), appeared on the peripheries of the late Xiongnu confederation about 200 BCE (contemporaneous with the Chinese Han Dynasty) and later among the Turkic-speaking Tiele as Hegu (紇骨) and Xue (薛). It has even been suggested that the Xiongnu themselves, who were mentioned in Han Dynasty records, were Proto-Turkic speakers.Although little is known for certain about the Xiongnu language(s), it seems likely that at least a considerable part of Xiongnu tribes spoke a Turkic language. Some scholars believe they were probably a confederation of various ethnic and linguistic groups. A genetic research in 2003, on skeletons from a 2000 year old Xiongnu necropolis in Mongolia, found individuals with similar DNA sequences as modern Turkic groups, supporting the view that at least parts of the Xiongu were of Turkic origin.

Xiongnu writing, older than Turkic, is agreed to have the earliest known Turkic alphabet, the Orkhon script. This has been argued recently using the only extant possibly Xiongu writings, the rock art of the Yinshan and Helan Mountains. Petroglyphs of this region dates from the 9th millennium BCE to the 19th century, and consists mainly of engraved signs (petroglyphs) and few painted images. Excavations done during 1924–1925 in Noin-Ula kurgans located in the Selenga River in the northern Mongolian hills north of Ulaanbaatar produced objects with over 20 carved characters, which were either identical or very similar to the runic letters of the Turkic Orkhon script discovered in the Orkhon Valley.

Huns (4th–6th c. CE)

Huns (c.450 CE)

The Hun hordes ruled by Attila, who invaded and conquered much of Europe in the 5th century, might have been, at least partially, Turkic and descendants of the Xiongnu.In the 18th century, the French scholar Joseph de Guignes became the first to propose a link between the Huns and the Xiongnu people, who were northern neighbours of China in the 3rd century BC. Since Guignes’ time, considerable scholarly effort has been devoted to investigating such a connection. The issue remains controversial. Their relationships to other peoples known collectively as the Iranian Huns are also disputed.

Some scholars regard the Huns as one of the earlier Turkic tribes, while others view them as Proto-Mongolian or Yeniseian in origin.Linguistic studies by Otto Maenchen-Helfen and others have suggested that the language used by the Huns in Europe was too little documented to be classified. Nevertheless, many of the proper names used by Huns appear to be Turkic in origin.

Turkic peoples originally used their own alphabets, like Orkhon and Yenisey runiforms, and later the Uyghur alphabet. Traditional national and cultural symbols of the Turkic peoples include wolves in Turkic mythology and tradition; as well as the color blue, iron, and fire. Turquoise blue (the word turquoise comes from the French word meaning “Turkish”) is the color of the stone turquoise still used in jewelry and as a protection against the evil eye.

Steppe expansions

Göktürks – Turkic Khaganate (5th–8th c.)

First Turk Khaganate (600 CE)

The Eastern and Western Turkic Khaganates (600 CE)

The first mention of Turks was in a Chinese text that mentioned trade between Turk tribes and the Sogdians along the Silk Road. The Ashina clan migrated from Li-jien (modern Zhelai Zhai) to the Rourans seeking inclusion in their confederacy and protection from the prevalent dynasty. The Ashina tribe were famed metalsmiths and were granted land near a mountain quarry which looked like a helmet, from which they were said to have gotten their name 突厥 (tūjué), the first recorded use of “Turk” as a political name. In the 6th-century, Ashina’s power had increased such that they conquered the Tiele on their Rouran overlords’ behalf and even overthrew Rourans and established the First Turkic Khaganate.

In the 6th century, 400 years after the collapse of northern Xiongnu power in Inner Asia, the Göktürks assumed leadership of the Turkic peoples. Formerly in the Xiongnu nomadic confederation, the Göktürks inherited their traditions and administrative experience. From 552 to 745, Göktürk leadership united the nomadic Turkic tribes into the Göktürk Empire on Mongolia and Central Asia. The name derives from gok, “blue” or “celestial”. Unlike its Xiongnu predecessor, the Göktürk Khaganate had its temporary Khagans from the Ashina clan, who were subordinate to a sovereign authority controlled by a council of tribal chiefs. The Khaganate retained elements of its original animistic-shamanistic religion, that later evolved into Tengriism, although it received missionaries of Buddhist monks and practiced a syncretic religion. The Göktürks were the first Turkic people to write Old Turkic in a runic script, the Orkhon script. The Khaganate was also the first state known as “Turk”. It eventually collapsed due to a series of dynastic conflicts, but many states and peoples later used the name “Turk”.

The Göktürks (First Turkic Kaganate) quickly spread west to the Caspian Sea. Between 581 and 603 the Western Turkic Khaganate in Kazakhstan separated from the Eastern Turkic Khaganate in Mongolia and Manchuria during a civil war. The Han-Chinese successfully overthrew the Eastern Turks in 630 and created a military Protectorate until 682. After that time the Second Turkic Khaganate ruled large parts of the former Göktürk area. After several wars between Turks, Chinese and Tibetans, the weakened Second Turkic Khaganate was replaced by the Uyghur Khaganate in the year 744.

Bulgars, Golden Horde and the Siberian Khanate

The migration of the Bulgars after the fall of Old Great Bulgaria in the 7th century

The Bulgars established themselves in between the Caspian and Black Seas in the 5th and 6th centuries, followed by their conquerors, the Khazars who converted to Judaism in the 8th or 9th century. After them came the Pechenegs who created a large confederacy, which was subsequently taken over by the Cumans and the Kipchaks. One group of Bulgars settled in the Volga region and mixed with local Volga Finnsto become the Volga Bulgars in what is today Tatarstan. These Bulgars were conquered by the Mongols following their westward sweep under Genghis Khan in the 13th century. Other Bulgars settled in Southeastern Europe in the 7th and 8th centuries, and mixed with the Slavic population, adopting what eventually became the Slavic Bulgarian language. Everywhere, Turkic groups mixed with the local populations to varying degrees.

Golden Horde

The Volga Bulgaria became an Islamic state in 922 and influenced the region as it controlled many trade routes. In the 13th century, Mongols invaded Europe and established the Golden Horde in Eastern Europe, western & northern Central Asia, and even western Siberia. The Cuman-Kipchak Confederation and Islamic Volga Bulgaria were absorbed by the Golden Horde in the 13th century; in the 14th century, Islam became the official religion under Uzbeg Khan where the general population (Turks) as well as the aristocracy (Mongols) came to speak the Kipchak language and were collectively known as “Tatars” by Russians and Westerners. This country was also known as the Kipchak Khanate and covered most of what is today Ukraine, as well as the entirety of modern-day southern and eastern Russia (the European section). The Golden Horde disintegrated into several khanates and hordes in the 15th and 16th century including the Crimean Khanate, Khanate of Kazan, and Kazakh Khanate (among others), which were one by one conquered and annexed by the Russian Empire in the 16th through 19th centuries.

In Siberia, the Siberian Khanate was established in the 1490s by fleeing Tatar aristocrats of the disintegrating Golden Horde who established Islam as the official religion in western Siberia over the partly Islamized native Siberian Tatars and indigenous Uralic peoples. It was the northernmost Islamic state in recorded history and it survived up until 1598 when it was conquered by Russia.

Uyghur Khaganate (8th–9th c.)

Uyghur Khaganate

Uyghur royals

The Uyghur empire ruled large parts of Mongolia, Northern and Western China and parts of northern Manchuria. They followed largely Buddhism and animistic traditions. During the same time, the Shatuo Turks emerged as power factor in Northern and Central China and were recognized by the Tang Empire as allied power. The Uyghur empire fell after several wars in the year 840.

The Turkic Later Tang Dynasty

The Shatuo Turks had founded several short-lived sinicized dynasties in northern China during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. The official language of these dynasties was Chinese and they used Chinese titles and names. Some Shaotuo Turks emperors also claimed patrilineal Han Chinese ancestry.

After the fall of the Tang-Dynasty in 907, the Shatuo Turks replaced them and created the Later Tang Dynasty in 923. The Shatuo Turks ruled over a large part of northern China, including Beijing. They adopted Chinese names and united Turkic and Chinese traditions. Later Tang fall in 937 but the Shatuo rose to become one of the most powerful clans of China. They created several other dynasies, including the Later Jinand Later Han. The Shatuo Turks were later assimilated into the Han Chinese ethnic group after they were conquered by the Song dynasty.

The Yenisei Kyrgyz allied with China to destroy the Uyghur Khaganate in 840. The Kyrgyz people ultimately settled in the region now referred to as Kyrgyzstan.

Central Asia

Kangar union (659–750)

Kangar Union after the fall of Western Turkic Khaganate, 659–750

The Kangar Union (Qanghar Odaghu) was a Turkic state in the former territory of the Western Turkic Khaganate (the entire present-day state of Kazakhstan, without Zhetysu). The ethnic name Kangar is a medieval name for the Kanglypeople, who are now part of the Kazakh, Uzbek, and Karakalpak nations. The capital of the Kangar union was located in the Ulytau mountains. The Pechenegs, three of whose tribes were known as Kangar (Greek: Καγγαρ), after being defeated by the Oghuzes, Karluks, and Kimek-Kypchaks, attacked the Bulgars and established the Pecheneg state in Eastern Europe (840–990 CE).

Oghuz Yabgu State (766–1055)

Oghuz Yabgu State (c.750 CE)

The Oguz Yabgu State (Oguz il, meaning “Oguz Land,”, “Oguz Country”)(750–1055) was a Turkicstate, founded by Oghuz Turks in 766, located geographically in an area between the coasts of the Caspian and Aral Seas. Oguz tribes occupied a vast territory in Kazakhstan along the Irgiz, Yaik, Emba, and Uil rivers, the Aral Sea area, the Syr Darya valley, the foothills of the Karatau Mountains in Tien-Shan, and the Chui River valley (see map). The Oguz political association developed in the 9th and 10th centuries in the basin of the middle and lower course of the Syr Darya and adjoining the modern western Kazakhstan steppes.

Iranian, Indian, Arabic, and Anatolian expansion

Turkic peoples and related groups migrated west from Northeastern China, present-day Mongolia, Siberia and the Turkestan-region towards the Iranian plateau, South Asia, and Anatolia (modern Turkey) in many waves. The date of the initial expansion remains unknown.

Persia

Ghaznavid Empire at its greatest extent in 1030 CE

The Ghaznavid dynasty (Persian: غزنویان ġaznaviyān) was a Persianate Muslim dynasty of Turkic mamluk origin, at their greatest extent ruling large parts of Iran, Afghanistan, much of Transoxiana and the northwest Indian subcontinent (part of Pakistan) from 977 to 1186. The dynasty was founded by Sabuktigin upon his succession to rule of the region of Ghazna after the death of his father-in-law, Alp Tigin, who was a breakaway ex-general of the Samanid Empire from Balkh, north of the Hindu Kush in Greater Khorasan.

Although the dynasty was of Central Asian Turkic origin, it was thoroughly Persianised in terms of language, culture, literature and habits and hence is regarded by some as a “Persian dynasty”.

Seljuk Empire (1037–1194)

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2019)

|

A map showing the Seljuk Empire at its height, upon the death of Malik Shah I in 1092.

Head of Seljuq male royal figure, 12–13th century, from Iran.

The Seljuk Empire (Persian: آل سلجوق, romanized: Āl-e Saljuq, lit. ‘House of Saljuq’) or the Great Seljuq Empire was a high medievalTurko-Persian Sunni Muslim empire, originating from the Qiniq branch of Oghuz Turks. At its greatest extent, the Seljuk Empire controlled a vast area stretching from western Anatolia and the Levant to the Hindu Kush in the east, and from Central Asia to the Persian Gulf in the south.

The Seljuk empire was founded by Tughril Beg (1016–1063) and his brother Chaghri Beg (989–1060) in 1037. From their homelands near the Aral Sea, the Seljuks advanced first into Khorasan and then into mainland Persia, before eventually conquering eastern Anatolia. Here the Seljuks won the battle of Manzikert in 1071 and conquered most of Anatolia from the Byzantine Empire, which became one of the reasons for the first crusade (1095–1099). From c. 1150–1250, the Seljuk empire declined, and was invaded by the Mongols around 1260. The Mongols divided Anatolia into emirates. Eventually one of these, the Ottoman, would conquer the rest.

Timurid Empire (1370–1507)

Map of the Timurid Empire at its greatest extent under Timur.

The Timurid Empire were a Turko-Mongol empire founded in the late 14th century by Timurlane, a descendant of Genghis Khan. Timur, although a self-proclaimed devout Muslim, brought great slaughter in his conquest of fellow Muslims in neighboring Islamic territory and contributed to the ultimate demise of many Muslim states, including the Golden Horde.

Central Asian khanates (1501–1920)

The Bukhara Khanate was an Uzbek state that existed from 1501 to 1785. The khanate was ruled by three dynasties of the Shaybanids, Janids and the Uzbek dynasty of Mangits. In 1785, Shahmurad, formalized the family’s dynastic rule (Manghit dynasty), and the khanate became the Emirate of Bukhara (1785-1920). In 1710, the Kokand Khanate (1710-1876) separated from the Bukhara Khanate. In 1511-1920, Khwarazm (Khiva Khanate) was ruled by the Arabshahid dynasty and the Uzbek dynasty of Kungrats.

Safavid dynasty (1501–1736)

The Safavid dynasty of Persia (1501–1736) were of mixed ancestry (Kurdish and Azerbaijani, which included intermarriages with Georgian, Circassian, and Pontic Greek dignitaries). Through intermarriage and other political considerations, the Safavids spoke Persian and Turkish, and some of the Shahs composed poems in their native Turkish language. Concurrently, the Shahs themselves also supported Persian literature, poetry and art projects including the grand Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp. The Safavid dynasty ruled parts of Greater Iran for more than two centuries. and established the Twelver school of Shi’a Islam as the official religion of their empire, marking one of the most important turning points in Muslim history

Afsharid dynasty (1736-1796)

The Afsharid dynasty was named after the Turkic Afshar tribe to which they belonged. The Afshars had migrated from Turkestan to Azerbaijan in the 13th century. The dynasty was founded in 1736 by the military commander Nader Shah who deposed the last member of the Safavid dynasty and proclaimed himself King of Iran. Nader belonged to the Qereqlu branch of the Afshars. During Nader’s reign, Iran reached its greatest extent since the Sassanid Empire.

South Asia

The Delhi Sultanate is a term used to cover five short-lived, Delhi-based kingdoms three of which were of Turkic origin in medieval India. These Turkic dynasties were the Mamluk dynasty (1206–90); the Khalji dynasty (1290–1320); and the Tughlaq dynasty (1320–1414). Southern Indiaalso saw many Turkic origin dynasties like the Bahmani Sultanate, the Adil Shahi dynasty, the Bidar Sultanate, and the Qutb Shahi dynasty, collectively known as the Deccan sultanates. The Mughal Empire was a Turko-Mongol founded Indian empire that, at its greatest territorial extent, ruled most of South Asia, including Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and parts of Uzbekistan from the early 16th to the early 18th centuries. The Mughal dynasty was founded by a Chagatai Turkic prince named Babur (reigned 1526–30), who was descended from the Turkic conqueror Timur (Tamerlane) on his father’s side and from Chagatai, second son of the Mongol ruler Genghis Khan, on his mother’s side. A further distinction was the attempt of the Mughals to integrate Hindus and Muslims into a united Indian state.

Arabian world

Silver dirham of AH 329 (940/941 CE), with the names of Caliph al-Muttaqi and Amir al-umara Bajkam (de facto ruler of the country)

The Arab Muslim Umayyads and Abbasids fought against the pagan Turks in the Türgesh Khaganate in the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana. The Medieval Arabs recorded that Medieval Turks looked strange from their perspective and were extremely physically different from the Arabs, calling them “broad faced people with small eyes”. Medieval Muslim writers noted that Tibetans and Turks resembled each other, and that they often were not able to tell the difference between Turks and Tibetans.

Turkic soldiers in the army of the Abbasid caliphs emerged as the de facto rulers of most of the Muslim Middle East (apart from Syria and Egypt), particularly after the 10th century. The Oghuz and other tribes captured and dominated various countries under the leadership of the Seljuk dynasty and eventually captured the territories of the Abbasid dynasty and the Byzantine Empire.

Anatolia – Ottomans

After many battles, the western Oghuz Turks established their own state and later constructed the Ottoman Empire. The main migration of the Oghuz Turks occurred in medieval times, when they spread across most of Asia and into Europe and the Middle East. They also took part in the military encounters of the Crusades. In 1090–91, the Turkic Pechenegs reached the walls of Constantinople, where Emperor Alexius I with the aid of the Kipchaks annihilated their army.

As the Seljuk Empire declined following the Mongol invasion, the Ottoman Empire emerged as the new important Turkic state, that came to dominate not only the Middle East, but even southeastern Europe, parts of southwestern Russia, and northern Africa.

Islamization

Turkic peoples like the Karluks (mainly 8th century), Uyghurs, Kyrgyz, Kazakhs, and Turkmens later came into contact with Muslims, and most of them gradually adopted Islam. Some groups of Turkic people practice other religions, including their original animistic-shamanistic religion, Christianity, Burkhanism, Jews (Khazars, Krymchaks, Crimean Karaites), Buddhism and a small number of Zoroastrians.

Modern history

Independent Turkic states shown in red

The Ottoman Empire gradually grew weaker in the face of poor administration, repeated wars with Russia, Austria and Hungary, and the emergence of nationalist movements in the Balkans, and it finally gave way after World War I to the present-day Republic of Turkey. Ethnic nationalism also developed in Ottoman Empire during the 19th century, taking the form of Pan-Turkism or Turanism.

The Turkic peoples of Central Asia were not organized in nation-states during most of the 20th century, after the collapse of the Russian Empire living either in the Soviet Union or (after a short-lived First East Turkestan Republic) in the Chinese Republic.

In 1991, after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, five Turkic states gained their independence. These were Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Other Turkic regions such as Tatarstan, Tuva, and Yakutiaremained in the Russian Federation. Chinese Turkestan remained part of the People’s Republic of China.

Immediately after the independence of the Turkic states, Turkey began seeking diplomatic relations with them. Over time political meetings between the Turkic countries increased and led to the establishment of TÜRKSOY in 1993 and later the Turkic Council in 2009.

Archaeology

- Xinglongwa culture

- Hongshan culture

- Čaatas culture

- Kurumchi culture

- Saltovo-Mayaki

- Tashtyk culture

- Saimaluu Tash

- Bilär

- Por-Bazhyn

- Ordu-Baliq

- Jankent

International organizations

Map of TÜRKSOY members.

There are several international organizations created with the purpose of furthering cooperation between countries with Turkic-speaking populations, such as the Joint Administration of Turkic Arts and Culture (TÜRKSOY) and the Parliamentary Assembly of Turkic-speaking Countries (TÜRKPA) and the Turkic Council.

The TAKM – Organization of the Eurasian Law Enforcement Agencies with Military Status, was established on 25 January 2013. It is an intergovernmental military law enforcement (gendarmerie) organization of currently three Turkic countries (Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan and Turkey) and Kazakhstan as observer.

TÜRKSOY

Türksoy carries out activities to strengthen cultural ties between Turkic peoples. One of the main goals to transmit their common cultural heritage to future generations and promote it around the world.

Every year, one city in the Turkic world is selected as the “Cultural Capital of the Turkic World”. Within the framework of events to celebrate the Cultural Capital of the Turkic World, numerous cultural events are held, gathering artists, scholars and intellectuals, giving them the opportunity to exchange their experiences, as well as promoting the city in question internationally.

Turkic Council

The newly established Turkic Council, founded on November 3, 2009 by the Nakhchivan Agreement confederation, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstanand Turkey, aims to integrate these organizations into a tighter geopolitical framework.

The member countries are Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkey and Uzbekistan. The idea of setting up this cooperative council was first put forward by Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev back in 2006. Turkmenistan is currently not an official member of the council, however, it is a possible future member of the council. Hungaryhas announced to be interested in joining the Turkic council. Since August 2018, Hungary has official observer status in the Turkic Council.

Demographics

Bashkirs, painting from 1812, Paris

The distribution of people of Turkic cultural background ranges from Siberia, across Central Asia, to Southern Europe. As of 2011 the largest groups of Turkic people live throughout Central Asia—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Azerbaijan, in addition to Turkeyand Iran. Additionally, Turkic people are found within Crimea, Altishahr region of western China, northern Iraq, Israel, Russia, Afghanistan, Cyprus, and the Balkans: Moldova, Bulgaria, Romania, Greece and former Yugoslavia. A small number of Turkic people also live in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania. Small numbers inhabit eastern Poland and the south-eastern part of Finland. There are also considerable populations of Turkic people (originating mostly from Turkey) in Germany, United States, and Australia, largely because of migrations during the 20th century.

Sometimes ethnographers group Turkic people into six branches: the Oghuz Turks, Kipchak, Karluk, Siberian, Chuvash, and Sakha/Yakutbranches. The Oghuz have been termed Western Turks, while the remaining five, in such a classificatory scheme, are called Eastern Turks.

The genetic distances between the different populations of Uzbeks scattered across Uzbekistan is no greater than the distance between many of them and the Karakalpaks. This suggests that Karakalpaks and Uzbeks have very similar origins. The Karakalpaks have a somewhat greater bias towards the eastern markers than the Uzbeks.

Historical population:

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1 AD | 2–2.5 million? |

| 2013 | 150–200 million |

The following incomplete list of Turkic people shows the respective groups’ core areas of settlement and their estimated sizes (in millions):

| People | Primary homeland | Population | Modern language | Predominant religion and sect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turks | Turkey | 70 M | Turkish | Sunni Islam |

| Azerbaijanis | Iranian Azerbaijan, Republic of Azerbaijan | 30–35 M | Azerbaijani | Shia Islam (65%), Sunni Islam (35%)(Hanafi). |

| Uzbeks | Uzbekistan | 28.3 M | Uzbek | Sunni Islam |

| Kazakhs | Kazakhstan | 13.8 M | Kazakh | Sunni Islam |

| Uyghurs | Altishahr (China) | 9 M | Uyghur | Sunni Islam |

| Turkmens | Turkmenistan | 8 M | Turkmen | Sunni Islam |

| Tatars | Tatarstan (Russia) | 7 M | Tatar | Sunni Islam |

| Kyrgyzs | Kyrgyzstan | 4.5 M | Kyrgyz | Sunni Islam |

| Bashkirs | Bashkortostan (Russia) | 2 M | Bashkir | Sunni Islam |

| Crimean Tatars | Crimea (Russia/Ukraine) | 0.5 to 2 M | Crimean Tatar | Sunni Islam |

| Qashqai | Southern Iran (Iran) | 0.9 M | Qashqai | Shia Islam |

| Chuvashes | Chuvashia (Russia) | 1.7 M | Chuvash | Orthodox Christianity |

| Karakalpaks | Karakalpakstan (Uzbekistan) | 0.6 M | Karakalpak | Sunni Islam |

| Yakuts | Yakutia (Russia) | 0.5 M | Sakha | Orthodox Christianity |

| Kumyks | Dagestan (Russia) | 0.4 M | Kumyk | Sunni Islam |

| Karachays and Balkars | Karachay-Cherkessia and Kabardino-Balkaria(Russia) | 0.4 M | Karachay-Balkar | Sunni Islam |

| Tuvans | Tuva (Russia) | 0.3 M | Tuvan | Tibetan Buddhism |

| Gagauzs | Gagauzia (Moldova) | 0.2 M | Gagauz | Orthodox Christianity |

| Turkic Karaites and Krymchaks | Ukraine | 0.2 M | Karaim and Krymchak | Judaism |

Cuisine

Markets in the steppe region had a limited range of foodstuffs available—mostly grains, dried fruits, spices, and tea. Turks mostly herded sheep, goats and horses. Dairy was a staple of the nomadic diet and there are many Turkic words for various dairy products such as süt (milk), yagh (butter), ayran, qaymaq (similar to clotted cream), qi̅mi̅z (fermented mare’s milk) and qurut (dried yoghurt). During the Middle Ages Kazakh, Kyrgyz and Tatars, who were historically part of the Turkic nomadic group known as the Golden Horde, continued to develop new variations of dairy products.

Nomadic Turks cooked their meals in a qazan, a pot similar to a cauldron; a wooden rack called a qasqan can be used to prepare certain steamed foods, like the traditional meat dumplings called manti. They also used a saj, a griddle that was traditionally placed on stones over a fire, and shish. In later times, the Persian tava was borrowed from the Persians for frying, but traditionally nomadic Turks did most of their cooking using the qazan, saj and shish. Meals were served in a bowl, called a chanaq, and eaten with a knife (bïchaq) and spoon (qashi̅q). Both bowl and spoon were historically made from wood. Other traditional utensils used in food preparation included a thin rolling pin called oqlaghu, a colander called süzgu̅çh, and a grinding stone called tāgirmān.

Medieval grain dishes included preparations of whole grains, soups, porridges, breads and pastries. Fried or toasted whole grains were called qawïrmach, while köchä was crushed grain that was cooked with dairy products. Salma were broad noodles that could be served with boiled or roasted meat; cut noodles were called tutmaj in the Middle Ages and are called kesme today.

There are many types of bread doughs in Turkic cuisine. Yupqa is the thinnest type of dough, bawi̅rsaq is a type of fried bread dough, and chälpäk is a deep fried flat bread. Qatlamais a fried bread that may be sprinkled with dried fruit or meat, rolled, and sliced like pinwheel sandwiches. Toqach and chöräk are varieties of bread, and böräk is a type of filled pie pastry.

Herd animals were usually slaughtered during the winter months and various types of sausages were prepared to preserve the meats, including a type of sausage called sujuk. Though prohibited by Islamic dietary restrictions, historically Turkic nomads also had a variety of blood sausage. One type of sausage, called qazi̅, was made from horsemeat and another variety was filled with a mixture of ground meat, offal and rice. Chopped meat was called qïyma and spit-roasted meat was söklünch—from the root sök- meaning “to tear off”, the latter dish is known as kebab in modern times. Qawirma is a typical fried meat dish, and kullama is a soup of noodles and lamb.

Religion

Early Turkic mythology and Tengrism

A shaman doctor of Kyzyl.

Pre-Islamic Turkic mythology was dominated by Shamanism, Animism and Tengrism. The Turkic animistic traditions were mostly focused on ancestor worship, polytheistic-animism and shamanism. Later this animistic tradition would form the more organized Tengrism. The chief deity was Tengri, a sky god, worshipped by the upper classes of early Turkic society until Manichaeism was introduced as the official religion of the Uyghur Empire in 763.

The wolf symbolizes honour and is also considered the mother of most Turkic peoples. Asena (Ashina Tuwu) is the wolf mother of Tumen Il-Qağan, the first Khan of the Göktürks. The horse and predatory birds, such as the eagle or falcon, are also main figures of Turkic mythology.

Religious conversions

Buddhism

Tengri Bögü Khan made the now extinct Manichaeism the state religion of Uyghur Khaganate in 763 and it was also popular in Karluks. It was gradually replaced by the Mahayana Buddhism. It existed in the Buddhist Uyghur Gaochang up to the 12th century.

Tibetan Buddhism, or Vajrayana was the main religion after Manichaeism. They worshipped Täŋri Täŋrisi Burxan, Quanšï Im Pusar and Maitri Burxan. Turkic Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent and west Xinjiang attributed with a rapid and almost total disappearance of it and other religions in North India and Central Asia. The Sari Uygurs”Yellow Yughurs” of Western China, as well as the Tuvans and Altai of Russia are the only remaining Buddhist Turkic peoples.

Islam

Most Turkic people today are Sunni Muslims, although a significant number in Turkey are Alevis. Alevi Turks, who were once primarily dwelling in eastern Anatolia, are today concentrated in major urban centers in western Turkey with the increased urbanism. Azeris are traditionally Shiite Muslims. Religious observance is less stricter in the Republic of Azerbaijan compared to Iranian Azerbaijan.

The major Christian-Turkic peoples are the Chuvash of Chuvashia and the Gagauz (Gökoğuz) of Moldova. The traditional religion of the Chuvash of Russia, while containing many ancient Turkic concepts, also shares some elements with Zoroastrianism, Khazar Judaism, and Islam. The Chuvash converted to Eastern Orthodox Christianity for the most part in the second half of the 19th century. As a result, festivals and rites were made to coincide with Orthodox feasts, and Christian rites replaced their traditional counterparts. A minority of the Chuvash still profess their traditional faith. Church of the East was popular among Turks such as the Naimans. It even revived in Gaochang and expanded in Xinjiang in the Yuan dynasty period. It disappeared after its collapse.

Today there are several groups that support a revival of the ancient traditions. Especially after the collapse of the Soviet Union, many in Central Asia converted or openly practice animistic and shamanistic rituals. It is estimated that about 60% of Kyrgyz people practice a form of animistic rituals. In Kazakhstan there are about 54.000 followers of the ancient traditions.

Muslim Turks and non-Muslim Turks

Uyghur king from Turpan region attended by servants

Kara-Khanids performed a mass conversion campaign against the Buddhist Uyghur Turks during the Islamization and Turkification of Xinjiang.

The non-Muslim Turks worship of Tengri and other gods was mocked and insulted by the Muslim Turk Mahmud al-Kashgari, who wrote a verse referring to them – The Infidels – May God destroy them!

The Basmil, Yabāḳu and Uyghur states were among the Turkic peoples who fought against the Kara-Khanids spread of Islam. The Islamic Kara-Khanids were made out of Tukhai, Yaghma, Çiğil and Karluk.

Kashgari claimed that the Prophet assisted in a miraculous event where 700,000 Yabāqu infidels were defeated by 40,000 Muslims led by Arslān Tegīn claiming that fires shot sparks from gates located on a green mountain towards the Yabāqu. The Yabaqu were a Turkic people.

Mahmud al-Kashgari insulted the Uyghur Buddhists as “Uighur dogs” and called them “Tats”, which referred to the “Uighur infidels” according to the Tuxsi and Taghma, while other Turks called Persians “tat”. While Kashgari displayed a different attitude towards the Turks diviners beliefs and “national customs”, he expressed towards Buddhism a hatred in his Diwan where he wrote the verse cycle on the war against Uighur Buddhists. Buddhist origin words like toyin (a cleric or priest) and Burxān or Furxan (meaning Buddha, acquiring the generic meaning of “idol” in the Turkic language of Kashgari) had negative connotations to Muslim Turks.

Göktürk petroglyphs from Mongolia (6th to 8th century)

An Uyghur Khagan

Old sports

Tepuk

Mahmud al-Kashgari in his Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk, described a game called “tepuk” among Turks in Central Asia. In the game, people try to attack each other’s castle by kicking a ball made of sheep leather.

Kyz kuu

Kyz kuu.

Kyz kuu (chase the girl) has been played by Turkic people at festivals since time immemorial.

Jereed

Horses have been essential and even sacred animals for Turks living as nomadic tribes in the Central Asian steppes. Turks were born, grew up, lived, fought and died on horseback. Jereed became the most important sporting and ceremonial game of Turkish people.

Kokpar

The kokpar began with the nomadic Turkic peoples who have come from farther north and east spreading westward from China and Mongolia between the 10th and 15th centuries.

Jigit

jigit” is used in the Caucasus and Central Asia to describe a skillful and brave equestrian, or a brave person in general.

Gallery

Bezeklik caves and Mogao grottoes

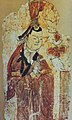

Images of Buddhist and Manichean Turkic Uyghurs from the Bezeklik caves and Mogao grottoes.

-

Uyghur king from Turfan, from the murals at the Dunhuang Mogao Caves.

-

Uyghur prince from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Uyghur woman from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Uyghur Princess.

-

Uyghur Princesses from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Uyghur Princes from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Uyghur Prince from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Uyghur noble from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Uyghur ManichaeanElect depicted on a temple banner from Qocho.

-

Uyghur donor from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Uyghur Manichaean Electae from Qocho.

-

Uyghur Manichaean clergymen from Qocho.

-

Fresco of Palm Sunday from Qocho.

-

Manicheans from Qocho

Medieval times

-

Khan Omurtag of Bulgaria, from the Chronicle of John Skylitzes.