Spanish (![]() español (help·info) or

español (help·info) or ![]() castellano (help·info), lit. ’Castilian’) is a Romance language that originated in the Iberian Peninsula of Europe. Today, it is a global language with nearly 500 million native speakers, mainly in Spain and the Americas. It is the world’s second-most spoken native language after Mandarin Chinese, and the world’s fourth-most spoken language overall after English, Mandarin Chinese, and Hindi.

castellano (help·info), lit. ’Castilian’) is a Romance language that originated in the Iberian Peninsula of Europe. Today, it is a global language with nearly 500 million native speakers, mainly in Spain and the Americas. It is the world’s second-most spoken native language after Mandarin Chinese, and the world’s fourth-most spoken language overall after English, Mandarin Chinese, and Hindi.

Spanish is a part of the Ibero-Romance group of languages of the Indo-European language family, which evolved from several dialects of Vulgar Latin in Iberia after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century. The oldest Latin texts with traces of Spanish come from mid-northern Iberia in the 9th century, and the first systematic written use of the language happened in Toledo, a prominent city of the Kingdom of Castile, in the 13th century. Modern Spanish was then taken to the viceroyalties of the Spanish Empire beginning in 1492, most notably to the Americas, as well as territories in Africa and the Philippines.

As a Romance language, Spanish is a descendant of Latin and has one of the smaller degrees of difference from it (about 20%) alongside Sardinian and Italian. Around 75% of modern Spanish vocabulary is derived from Latin, including Latin borrowings from Ancient Greek. As in other Romance languages, the abundance of Classical Greek words (Hellenisms) incorporated in the Spanish language have notably influenced the vocabulary of elemental areas like nature, science, politics, literature, philosophy, arts, music, etc.

Due to both its complex history and the formation of its global empire, the Spanish language has received some influences from many different languages: Around 8% of the Spanish dictionary words has an Arabic lexical root, having developed during the contact with Al-Andalus. It has also been influenced by Basque, Iberian, Celtiberian and Visigothic, the latter having developed particularly during the Visigothic Kingdom of the Iberian Peninsula. Additionally, it has absorbed vocabulary from other languages, particularly other Romance languages such as French, Italian, Portuguese, Galician, Catalan, Mozarabic, Occitan, and Sardinian, as well as from Quechua, Nahuatl, and other indigenous languages of the Americas.

Spanish is one of the six official languages of the United Nations, and it is also used as an official language by the European Union, the Organization of American States, the Union of South American Nations, the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, the African Union and many other international organizations. Alongside English and French, it is also one of the most taught foreign languages throughout the world. Spanish doesn’t feature prominently as a scientific language, however, it’s better represented in areas like humanities and social sciences. Spanish is also the third most used language on internet websites after English and Chinese.

Name of the language and etymology

Map indicating places where the language is called castellano (in red) or español (in blue)

Name of the language

In Spain and in some other parts of the Spanish-speaking world, Spanish is called not only español but also castellano (Castilian), the language from the kingdom of Castile, contrasting it with other languages spoken in Spain such as Galician, Basque, Asturian, Catalan, Aragonese and Occitan.

The Spanish Constitution of 1978 uses the term castellano to define the official language of the whole Spanish State in contrast to las demás lenguas españolas (lit. “the other Spanish languages”). Article III reads as follows:

El castellano es la lengua española oficial del Estado. … Las demás lenguas españolas serán también oficiales en las respectivas Comunidades Autónomas…

Castilian is the official Spanish language of the State. … The other Spanish languages shall also be official in their respective Autonomous Communities…

The Royal Spanish Academy (Real Academia Española), on the other hand, currently uses the term español in its publications, but from 1713 to 1923 called the language castellano.

The Diccionario panhispánico de dudas (a language guide published by the Royal Spanish Academy) states that, although the Royal Spanish Academy prefers to use the term español in its publications when referring to the Spanish language, both terms—español and castellano—are regarded as synonymous and equally valid.

Etymology

The term castellano comes from the Latin word castellanus, which means “of or pertaining to a fort or castle”.

Different etymologies have been suggested for the term español (Spanish). According to the Royal Spanish Academy, español derives from the Provençal word espaignol and that, in turn, derives from the Vulgar Latin *hispaniolus. It comes from the Latin name of the province of Hispania that included the current territory of the Iberian Peninsula.

There are other hypotheses apart from the one suggested by the Royal Spanish Academy. Spanish philologist Menéndez Pidal suggested that the classic hispanus or hispanicus took the suffix -one from Vulgar Latin, as it happened with other words such as bretón (Breton) or sajón (Saxon). The word *hispanione evolved into the Old Spanish españón, which eventually, became español.

History

The Visigothic Cartularies of Valpuesta, written in a late form of Latin, were declared in 2010 by the Royal Spanish Academy as the record of the earliest words written in Castilian, predating those of the Glosas Emilianenses.

The Spanish language evolved from Vulgar Latin, which was brought to the Iberian Peninsula by the Romans during the Second Punic War, beginning in 210 BC. Previously, several pre-Roman languages (also called Paleohispanic languages)—some related to Latin via Indo-European, and some that are not related at all—were spoken in the Iberian Peninsula. These languages included Basque (still spoken today), Iberian, Celtiberian and Gallaecian.

The first documents to show traces of what is today regarded as the precursor of modern Spanish are from the 9th century. Throughout the Middle Ages and into the modern era, the most important influences on the Spanish lexicon came from neighboring Romance languages—Mozarabic (Andalusi Romance), Navarro-Aragonese, Leonese, Catalan, Portuguese, Galician, Occitan, and later, French and Italian. Spanish also borrowed a considerable number of words from Arabic, as well as a minor influence from the Germanic Gothic language through the migration of tribes and a period of Visigoth rule in Iberia. In addition, many more words were borrowed from Latin through the influence of written language and the liturgical language of the Church. The loanwords were taken from both Classical Latin and Renaissance Latin, the form of Latin in use at that time.

According to the theories of Ramón Menéndez Pidal, local sociolects of Vulgar Latin evolved into Spanish, in the north of Iberia, in an area centered in the city of Burgos, and this dialect was later brought to the city of Toledo, where the written standard of Spanish was first developed, in the 13th century. In this formative stage, Spanish developed a strongly differing variant from its close cousin, Leonese, and, according to some authors, was distinguished by a heavy Basque influence (see Iberian Romance languages). This distinctive dialect spread to southern Spain with the advance of the Reconquista, and meanwhile gathered a sizable lexical influence from the Arabic of Al-Andalus, much of it indirectly, through the Romance Mozarabic dialects (some 4,000 Arabic-derived words, make up around 8% of the language today). The written standard for this new language was developed in the cities of Toledo, in the 13th to 16th centuries, and Madrid, from the 1570s.

The development of the Spanish sound system from that of Vulgar Latin exhibits most of the changes that are typical of Western Romance languages, including lenition of intervocalic consonants (thus Latin vīta > Spanish vida). The diphthongization of Latin stressed short e and o—which occurred in open syllables in French and Italian, but not at all in Catalan or Portuguese—is found in both open and closed syllables in Spanish, as shown in the following table:

| Latin | Spanish | Ladino | Aragonese | Asturian | Galician | Portuguese | Catalan | Gascon / Occitan | French | Sardinian | Italian | Romanian | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| petra | piedra | pedra | pedra, pèira | pierre | pedra, perda | pietra | piatrǎ | ‘stone’ | |||||

| terra | tierra | terra | tèrra | terre | terra | țară | ‘land’ | ||||||

| moritur | muere | muerre | morre | mor | morís | meurt | mòrit | muore | moare | ‘dies (v.)’ | |||

| mortem | muerte | morte | mort | mòrt | mort | morte, morti | morte | moarte | ‘death’ | ||||

Chronological map showing linguistic evolution in southwest Europe

Spanish is marked by the palatalization of the Latin double consonants nn and ll (thus Latin annum > Spanish año, and Latin anellum > Spanish anillo).

The consonant written u or v in Latin and pronounced in Classical Latin had probably “fortified” to a bilabial fricative /β/ in Vulgar Latin. In early Spanish (but not in Catalan or Portuguese) it merged with the consonant written b (a bilabial with plosive and fricative allophones). In modern Spanish, there is no difference between the pronunciation of orthographic b and v, with some exceptions in Caribbean Spanish.

Peculiar to Spanish (as well as to the neighboring Gascon dialect of Occitan, and attributed to a Basque substratum) was the mutation of Latin initial f into h- whenever it was followed by a vowel that did not diphthongize. The h-, still preserved in spelling, is now silent in most varieties of the language, although in some Andalusian and Caribbean dialects it is still aspirated in some words. Because of borrowings from Latin and from neighboring Romance languages, there are many f-/h-doublets in modern Spanish: Fernando and Hernando (both Spanish for “Ferdinand”), ferrero and herrero (both Spanish for “smith”), fierro and hierro (both Spanish for “iron”), and fondo and hondo (both Spanish for “deep”, but fondo means “bottom” while hondo means “deep”); hacer (Spanish for “to make”) is cognate to the root word of satisfacer (Spanish for “to satisfy”), and hecho (“made”) is similarly cognate to the root word of satisfecho (Spanish for “satisfied”).

Compare the examples in the following table:

| Latin | Spanish | Ladino | Aragonese | Asturian | Galician | Portuguese | Catalan | Gascon / Occitan | French | Sardinian | Italian | Romanian | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| filium | hijo | fijo (or hijo) | fillo | fíu | fillo | filho | fill | filh, hilh | fils | fizu, fìgiu, fillu | figlio | fiu | ‘son’ |

| facere | hacer | fazer | fer | facer | fazer | fer | far, faire, har (or hèr) | faire | fàghere, fàere, fàiri | fare | a face | ‘to do’ | |

| febrem | fiebre (calentura) | febre | fèbre, frèbe, hrèbe (or herèbe) |

fièvre | calentura | febbre | febră | ‘fever’ | |||||

| focum | fuego | fueu | fogo | foc | fuòc, fòc, huèc | feu | fogu | fuoco | foc | ‘fire’ | |||

Some consonant clusters of Latin also produced characteristically different results in these languages, as shown in the examples in the following table:

| Latin | Spanish | Ladino | Aragonese | Asturian | Galician | Portuguese | Catalan | Gascon / Occitan | French | Sardinian | Italian | Romanian | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| clāvem | llave, clave | clave | clau | llave | chave | chave | clau | clé | giae, crae, crai | chiave | cheie | ‘key’ | |

| flamma | llama, flama | flama | chama | chama, flama | flama | flamme | framma | fiamma | flamă | ‘flame’ | |||

| plēnum | lleno, pleno | pleno | plen | llenu | cheo | cheio, pleno | ple | plen | plein | prenu | pieno | plin | ‘plenty, full’ |

| octō | ocho | güeito | ocho, oito | oito | oito (oito) | vuit, huit | uèch, uòch, uèit | huit | oto | otto | opt | ‘eight’ | |

| multum | mucho muy |

muncho muy |

muito mui |

munchu mui |

moito moi |

muito | molt | molt (arch.) | très,beaucoup, moult | meda | molto | mult | ‘much, very, many’ |

Antonio de Nebrija, author of Gramática de la lengua castellana, the first grammar of a modern European language.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, Spanish underwent a dramatic change in the pronunciation of its sibilant consonants, known in Spanish as the reajuste de las sibilantes, which resulted in the distinctive velar pronunciation of the letter ⟨j⟩ and—in a large part of Spain—the characteristic interdental (“th-sound”) for the letter ⟨z⟩ (and for ⟨c⟩ before ⟨e⟩ or ⟨i⟩). See History of Spanish (Modern development of the Old Spanish sibilants) for details.

The Gramática de la lengua castellana, written in Salamanca in 1492 by Elio Antonio de Nebrija, was the first grammar written for a modern European language. According to a popular anecdote, when Nebrija presented it to Queen Isabella I, she asked him what was the use of such a work, and he answered that language is the instrument of empire. In his introduction to the grammar, dated 18 August 1492, Nebrija wrote that “… language was always the companion of empire.”

From the sixteenth century onwards, the language was taken to the Spanish-discovered America and the Spanish East Indies via Spanish colonization of America. Miguel de Cervantes, author of Don Quixote, is such a well-known reference in the world that Spanish is often called la lengua de Cervantes (“the language of Cervantes”).

In the twentieth century, Spanish was introduced to Equatorial Guinea and the Western Sahara, and to areas of the United States that had not been part of the Spanish Empire, such as Spanish Harlem in New York City. For details on borrowed words and other external influences upon Spanish, see Influences on the Spanish language.

Geographical distribution

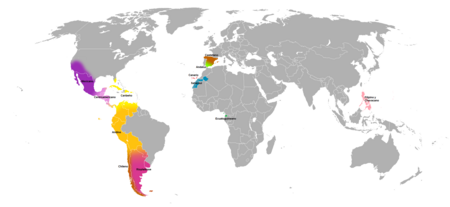

Geographical distribution of the Spanish language

Spanish is the primary language in 20 countries worldwide. As of 2020, it is estimated that about 463 million people speak Spanish as a native language, making it the second most spoken language by number of native speakers. An additional 75 million speak Spanish as a second or foreign language, making it the fourth most spoken language in the world overall after English, Mandarin Chinese, and Hindi with a total number of 538 million speakers. Spanish is also the third most used language on the Internet, after English and Russian.

Europe

Percentage of people who self reportedly know enough Spanish to hold a conversation, in the EU, 2005

In Europe, Spanish is an official language of Spain, the country after which it is named and from which it originated. It is also widely spoken in Gibraltar and Andorra.

Spanish is also spoken by immigrant communities in other European countries, such as the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Germany. Spanish is an official language of the European Union.

Americas

Hispanic America

Most Spanish speakers are in Hispanic America; of all countries with a majority of Spanish speakers, only Spain and Equatorial Guinea are outside the Americas. Nationally, Spanish is the official language—either de facto or de jure—of Argentina, Bolivia (co-official with Quechua, Aymara, Guarani, and 34 other languages), Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico (co-official with 63 indigenous languages), Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay (co-official with Guaraní), Peru (co-official with Quechua, Aymara, and “the other indigenous languages”), Puerto Rico (co-official with English), Uruguay, and Venezuela. Spanish has no official recognition in the former British colony of Belize; however, per the 2000 census, it is spoken by 43% of the population. Mainly, it is spoken by the descendants of Hispanics who have been in the region since the seventeenth century; however, English is the official language.

Due to their proximity to Spanish-speaking countries, Trinidad and Tobago and Brazil have implemented Spanish language teaching into their education systems. The Trinidad government launched the Spanish as a First Foreign Language (SAFFL) initiative in March 2005. In 2005, the National Congress of Brazil approved a bill, signed into law by the President, making it mandatory for schools to offer Spanish as an alternative foreign language course in both public and private secondary schools in Brazil. In September 2016 this law was revoked by Michel Temer after impeachment of Dilma Rousseff. In many border towns and villages along Paraguay and Uruguay, a mixed language known as Portuñol is spoken.

United States

Spanish spoken in the United States and Puerto Rico. Darker shades of green indicate higher percentages of Spanish speakers.

According to 2006 census data, 44.3 million people of the U.S. population were Hispanic or Hispanic American by origin; 38.3 million people, 13 percent of the population over five years old speak Spanish at home. The Spanish language has a long history of presence in the United States due to early Spanish and, later, Mexican administration over territories now forming the southwestern states, also Louisiana ruled by Spain from 1762 to 1802, as well as Florida, which was Spanish territory until 1821, and Puerto Rico which was Spanish until 1898.

Spanish is by far the most common second language in the US, with over 50 million total speakers if non-native or second-language speakers are included. While English is the de facto national language of the country, Spanish is often used in public services and notices at the federal and state levels. Spanish is also used in administration in the state of New Mexico. The language also has a strong influence in major metropolitan areas such as those of Los Angeles, Miami, San Antonio, New York, San Francisco, Dallas, and Phoenix; as well as more recently, Chicago, Las Vegas, Boston, Denver, Houston, Indianapolis, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Salt Lake City, Atlanta, Nashville, Orlando, Tampa, Raleigh and Baltimore-Washington, D.C. due to 20th- and 21st-century immigration.

Africa

Spanish language signage in Malabo, capital city of Equatorial Guinea.

In Africa, Spanish is official in Equatorial Guinea (alongside French and Portuguese), where it is the predominant language, while Fang is the most spoken language by number of native speakers. It is also an official language of the African Union.

Spanish is also spoken in the integral territories of Spain in North Africa, which include the cities of Ceuta and Melilla, the Canary Islands located some 100 km (62 mi) off the northwest coast of mainland Africa, and minuscule outposts known as plazas de soberanía. In northern Morocco, a former Spanish protectorate, approximately 20,000 people speak Spanish as a second language, while Arabic is the de jure official language and French is a second administrative language. Spanish is spoken by very small communities in Angola due to Cuban influence from the Cold War and in South Sudan among South Sudanese natives that relocated to Cuba during the Sudanese wars and returned for their country’s independence.

In Western Sahara, formerly Spanish Sahara, Spanish was officially spoken during the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Today, Spanish is present alongside Arabic in the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, although this entity receives limited international recognition and the number of Spanish speakers is unknown.

Asia

Spanish was an official language of the Philippines from the beginning of Spanish administration in 1565 to a constitutional change in 1973. During Spanish colonization (1565–1898), it was the language of government, trade, and education, and was spoken as a first language by Spaniards and educated Filipinos. In the mid-nineteenth century, the colonial government set up a free public education system with Spanish as the medium of instruction. While this increased the use of Spanish throughout the islands and led to the formation of a class of Spanish-speaking intellectuals called the Ilustrados, only populations in urban areas or with places with a significant Spanish presence used the language on a daily basis or learned it as a second or third language. By the end of Spanish rule in 1898, only about 10% of the population had knowledge of Spanish, mostly those of Spanish descent or elite standing.

Despite American administration of the Philippines after the defeat of Spain in the Spanish–American War, Spanish continued to be used in Philippine literature and press during the early years of American administration. Gradually however, the American government began promoting the use of English at the expense of Spanish, characterizing it as a negative influence of the past. Eventually, by the 1920s, English became the primary language of administration and education. Nevertheless, despite a significant decrease in influence and speakers, Spanish remained an official language of the Philippines upon independence in 1946, alongside English and Filipino, a standardized version of Tagalog.

Early flag of the Filipino revolutionaries (“Long live the Philippine Republic!!!”). The first two constitutions were written in Spanish.

Spanish was briefly removed from official status in 1973 under the administration of Ferdinand Marcos, but regained official status two months later under Presidential Decree No. 155, dated 15 March 1973. It remained an official language until 1987, with the ratification of the present constitution, in which it was re-designated as a voluntary and optional auxiliary language. In 2010, President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo encouraged the reintroduction of Spanish-language teaching in the Philippine education system. However, the initiative failed to gain any traction, with the number of secondary schools at which the language is either a compulsory subject or offered as an elective remaining very limited. Today, while the most optimistic estimates place the number of Spanish speakers in the Philippines at around 1.8 million people, interest in the language is growing, with some 20,000 students studying the language every year.

Aside from standard Spanish, a Spanish-based creole language called Chavacano developed in the southern Philippines. However, it is not mutually intelligible with Spanish. The number of Chavacano-speakers was estimated at 1.2 million in 1996. The local languages of the Philippines also retain significant Spanish influence, with many words derived from Mexican Spanish, owing to the administration of the islands by Spain through New Spain until 1821, until direct governance from Madrid afterwards to 1898.

Oceania

Announcement in Spanish on Easter Island, welcoming visitors to Rapa Nui National Park

Spanish is the official and most spoken language on Easter Island, which is geographically part of Polynesia in Oceania and politically part of Chile. However, Easter Island’s traditional language is Rapa Nui, an Eastern Polynesian language.

As a legacy of comprising the former Spanish East Indies, Spanish loan words are present in the local languages of Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Marshall Islands and Micronesia.

Grammar

Miguel de Cervantes, considered by many the greatest author of Spanish literature, and author of Don Quixote, widely considered the first modern European novel.

Most of the grammatical and typological features of Spanish are shared with the other Romance languages. Spanish is a fusional language. The noun and adjective systems exhibit two genders and two numbers. In addition, articles and some pronouns and determiners have a neuter gender in their singular form. There are about fifty conjugated forms per verb, with 3 tenses: past, present, future; 2 aspects for past: perfective, imperfective; 4 moods: indicative, subjunctive, conditional, imperative; 3 persons: first, second, third; 2 numbers: singular, plural; 3 verboid forms: infinitive, gerund, and past participle. The indicative mood is the unmarked one, while the subjunctive mood expresses uncertainty or indetermination, and is commonly paired with the conditional, which is a mood used to express “would” (as in, “I would eat if I had food); the imperative is a mood to express a command, commonly a one word phrase – “¡Di!”, “Talk!”.

Verbs express T-V distinction by using different persons for formal and informal addresses. (For a detailed overview of verbs, see Spanish verbs and Spanish irregular verbs.)

Spanish syntax is considered right-branching, meaning that subordinate or modifying constituents tend to be placed after head words. The language uses prepositions (rather than postpositions or inflection of nouns for case), and usually—though not always—places adjectives after nouns, as do most other Romance languages.

Spanish is classified as a subject–verb–object language; however, as in most Romance languages, constituent order is highly variable and governed mainly by topicalization and focus rather than by syntax. It is a “pro-drop”, or “null-subject” language—that is, it allows the deletion of subject pronouns when they are pragmatically unnecessary. Spanish is described as a “verb-framed” language, meaning that the direction of motion is expressed in the verb while the mode of locomotion is expressed adverbially (e.g. subir corriendo or salir volando; the respective English equivalents of these examples—’to run up’ and ‘to fly out’—show that English is, by contrast, “satellite-framed”, with mode of locomotion expressed in the verb and direction in an adverbial modifier).

Subject/verb inversion is not required in questions, and thus the recognition of declarative or interrogative may depend entirely on intonation.

Phonology

Spanish spoken in Spain

The Spanish phonemic system is originally descended from that of Vulgar Latin. Its development exhibits some traits in common with the neighboring dialects—especially Leonese and Aragonese—as well as other traits unique to Spanish. Spanish is unique among its neighbors in the aspiration and eventual loss of the Latin initial /f/ sound (e.g. Cast. harina vs. Leon. and Arag. farina). The Latin initial consonant sequences pl-, cl-, and fl- in Spanish typically become ll- (originally pronounced ), while in Aragonese they are preserved in most dialects, and in Leonese they present a variety of outcomes, including , , and . Where Latin had -li- before a vowel (e.g. filius) or the ending -iculus, -icula (e.g. auricula), Old Spanish produced , that in Modern Spanish became the velar fricative (hijo, oreja, where neighboring languages have the palatal lateral (e.g. Portuguese filho, orelha; Catalan fill, orella).

Segmental phonology

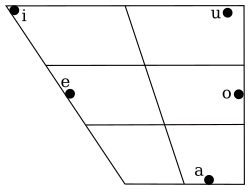

Spanish vowel chart, from Ladefoged & Johnson (2010:227)

The Spanish phonemic inventory consists of five vowel phonemes (/a/, /e/, /i/, /o/, /u/) and 17 to 19 consonant phonemes (the exact number depending on the dialect). The main allophonic variation among vowels is the reduction of the high vowels /i/ and /u/ to glides— and respectively—when unstressed and adjacent to another vowel. Some instances of the mid vowels /e/ and /o/, determined lexically, alternate with the diphthongs /je/ and /we/ respectively when stressed, in a process that is better described as morphophonemic rather than phonological, as it is not predictable from phonology alone.

The Spanish consonant system is characterized by (1) three nasal phonemes, and one or two (depending on the dialect) lateral phoneme(s), which in syllable-final position lose their contrast and are subject to assimilation to a following consonant; (2) three voiceless stops and the affricate /tʃ/; (3) three or four (depending on the dialect) voiceless fricatives; (4) a set of voiced obstruents—/b/, /d/, /ɡ/, and sometimes /ʝ/—which alternate between approximant and plosive allophones depending on the environment; and (5) a phonemic distinction between the “tapped” and “trilled” r-sounds (single ⟨r⟩ and double ⟨rr⟩ in orthography).

In the following table of consonant phonemes, /ʎ/ is marked with an asterisk (*) to indicate that it is preserved only in some dialects. In most dialects it has been merged with /ʝ/ in the merger called yeísmo. Similarly, /θ/ is also marked with an asterisk to indicate that most dialects do not distinguish it from /s/ (see seseo), although this is not a true merger but an outcome of different evolution of sibilants in Southern Spain.

The phoneme /ʃ/ is in parentheses () to indicate that it appears only in loanwords. Each of the voiced obstruent phonemes /b/, /d/, /ʝ/, and /ɡ/ appears to the right of a pair of voiceless phonemes, to indicate that, while the voiceless phonemes maintain a phonemic contrast between plosive (or affricate) and fricative, the voiced ones alternate allophonically (i.e. without phonemic contrast) between plosive and approximant pronunciations.

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | tʃ | ʝ | k | ɡ | ||

| Continuant | f | θ* | s | (ʃ) | x | |||||

| Lateral | l | ʎ* | ||||||||

| Flap | ɾ | |||||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||

Prosody

Spanish is classified by its rhythm as a syllable-timed language: each syllable has approximately the same duration regardless of stress.

Spanish intonation varies significantly according to dialect but generally conforms to a pattern of falling tone for declarative sentences and wh-questions (who, what, why, etc.) and rising tone for yes/no questions. There are no syntactic markers to distinguish between questions and statements and thus, the recognition of declarative or interrogative depends entirely on intonation.

Stress most often occurs on any of the last three syllables of a word, with some rare exceptions at the fourth-to-last or earlier syllables. Stress tends to occur as follows:

- in words that end with a monophthong, on the penultimate syllable

- when the word ends in a diphthong, on the final syllable.

- in words that end with a consonant, on the last syllable, with the exception of two grammatical endings: -n, for third-person-plural of verbs, and -s, for plural of nouns and adjectives or for second-person-singular of verbs. However, even though a significant number of nouns and adjectives ending with -n are also stressed on the penult (joven, virgen, mitin), the great majority of nouns and adjectives ending with -n are stressed on their last syllable (capitán, almacén, jardín, corazón).

- Preantepenultimate stress (stress on the fourth-to-last syllable) occurs rarely, only on verbs with clitic pronouns attached (e.g. guardándoselos ‘saving them for him/her/them/you’).

In addition to the many exceptions to these tendencies, there are numerous minimal pairs that contrast solely on stress such as sábana (‘sheet’) and sabana (‘savannah’); límite (‘boundary’), limite (‘he/she limits’) and limité (‘I limited’); líquido (‘liquid’), liquido (‘I sell off’) and liquidó (‘he/she sold off’).

The orthographic system unambiguously reflects where the stress occurs: in the absence of an accent mark, the stress falls on the last syllable unless the last letter is ⟨n⟩, ⟨s⟩, or a vowel, in which cases the stress falls on the next-to-last (penultimate) syllable. Exceptions to those rules are indicated by an acute accent mark over the vowel of the stressed syllable. (See Spanish orthography.)

Speaker population

Spanish is the official, or national language in 18 countries and one territory in the Americas, Spain, and Equatorial Guinea. With a population of over 410 million, Hispanophone America accounts for the vast majority of Spanish speakers, of which Mexico is the most populous Spanish-speaking country. In the European Union, Spanish is the mother tongue of 8% of the population, with an additional 7% speaking it as a second language. Additionally, Spanish is the second most spoken language in the United States and is by far the most popular foreign language among students. In 2015, it was estimated that over 50 million Americans spoke Spanish, about 41 million of whom were native speakers. With continued immigration and increased use of the language domestically in public spheres and media, the number of Spanish speakers in the United States is expected to continue growing over the forthcoming decades.

Spanish speakers by country

The following table shows the number of Spanish speakers in some 79 countries.

| Country | Population | Spanish as a native language speakers | Native speakers and proficient speakers as a second language | Total number of Spanish speakers (including limited competence speakers) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 128,972,439 | 119,557,451 (92.7%) | 124,845,321 (96,8%) | 127,037,852 (98.5%) | |

| 328,239,523 | 41,757,391 (13.5%) | 41,757,391(82% of U.S. Hispanics speak Spanish very well (according to a 2011 survey). There are 60.5 million Hispanics in the U.S. as of 2019 + 2.8 mill. non Hispanic Spanish speakers) | 56,657,391 (41.8 million as a first language + 14.9 million as a second language. To avoid double counting, the number does not include 8 million Spanish students and some of the 8.4 million undocumented Hispanics not accounted by the Census | |

| 51,049,498 | 50,199,498 (98.9%) | 50,641,102 (99.2%) | ||

| 47,332,614 | 37,868,912 (80%) | 46,383,381 (98%) | ||

| 45,808,747 | 44,297,059 (96.7%) | 44 938 381 (98,1%) | 45,533,895 (99.4%) | |

| 32,605,423 | 31,507,179 (1,098,244 with other mother tongue) | 31,725,077 (97.3%) | 32,214,158 (98.8%) | |

| 33,149,016 | 27,480,534 (82.9%) | 29,834,114 (86.6%) | ||

| 19,678,363 | 18,871,550 (281,600 with other mother tongue) | 18,871,550 (95.9%) | 19,540,614 (99.3%) | |

| 17,424,000 | 16 204 320 (93%) | 16,692,192 (95.8%) | 16,845,732 (98.1%) | |

| 18,055,025 | 12,620,462 (69.9%) | 14,137,085 (78.3%) | 15,599,542 (86.4%) | |

| 11,209,628 | 11 187 209 (99.8%) | 11,187,209 (99.8%) | ||

| 10,448,499 | 10 197 735 (97.6%) | 10 197 735 (97.6%) | 10,302,220 (99.6%) | |

| 11,584,000 | 7,031,488 (60.7%) | 9,614,720 (83%) | 10,182,336 (87.9%) | |

| 9,251,313 | 9 039 287 (207,750 with other mother tongue) | 9,039,287 (98.7%) | ||

| 6,765,753 | 6 745 456 | 6,745,456 (99.7%) | ||

| 65,635,000 | 477,564 (1% of 47,756,439) | 1,910,258 (4% of 47,756,439) | 6,685,901 (14% of 47,756,439) | |

| 6,218,321 | 6,037,990 (97.1%) (490,124 with other mother tongue) | 6,218,321 (180,331 limited proficiency) | ||

| 211,671,000 | 460,018 | 460,018 | 6,056,018 (460,018 native speakers + 96,000 limited proficiency + 5,500,000 can hold a conversation) | |

| 60,795,612 | 255,459 | 1,037,248 (2% of 51,862,391) | 5,704,863 (11% of 51,862,391) | |

| 4,890,379 | 4,806,069 (84,310 with other mother tongue) | 4,851,256 (99.2%) | ||

| 7,252,672 | 4,460,393 (61.5%) | 4,946,322 (68,2%) | ||

| 3,764,166 | 3,263,123 (501,043 with other mother tongue) | 3,504,439 (93.1%) | ||

| 3,480,222 | 3,330,022 (150,200 with other mother tongue) | 3,441,940 (98.9%) | ||

| 3,474,182 | 3,303,947 (95.1%) | 3,432,492 (98.8%) | ||

| 64,105,700 | 120,000 | 518,480 (1% of 51,848,010) | 3,110,880 (6% of 51,848,010) | |

| 101,562,305 | 438,882 | 3,016,773 | ||

| 81,292,400 | 644,091 (1% of 64,409,146) | 2,576,366 (4% of 64,409,146) | ||

| 34,378,000 | 6,586 | 6,586 | 1,664,823 (10%) | |

| 1,622,000 | 1,683 | 918,000 (90.5%) | ||

| 21,355,849 | 182,467 (1% of 18,246,731) | 912,337 (5% of 18,246,731) | ||

| 10,636,888 | 323,237 (4% of 8,080,915) | 808,091 (10% of 8,080,915) | ||

| 34,605,346 | 553,495 | 643,800 (87% of 740,000) | 736,653 | |

| 16,665,900 | 133,719 (1% of 13,371,980) | 668,599 (5% of 13,371,980 ) | ||

| 9,555,893 | 77,912 (1% of 7,791,240) | 77,912 (1% of 7,791,240) | 467,474 (6% of 7,791,240) | |

| 21,507,717 | 111,400 | 111,400 | 447,175 | |

| 10,918,405 | 89,395 (1% of 8,939,546) | 446,977 (5% of 8,939,546) | ||

| 10,008,749 | 412,515 (students) | |||

| 21,359,000 | 341,073 (students) | |||

| 38,092,000 | 324,137 (1% of 32,413,735) | 324,137 (1% of 32,413,735) | ||

| 8,205,533 | 70,098 (1% of 7,009,827) | 280,393 (4% of 7,009,827) | ||

| 33,769,669 | 223,422 | |||

| 333,200 | 173,597 | 173,597 | 195,597 (62.8%) | |

| 12,853,259 | 205,000 (students) | |||

| 5,484,723 | 45,613 (1% of 4,561,264) | 182,450 (4% of 4,561,264) | ||

| 7,112,359 | 130,000 | 175,231 | ||

| 127,288,419 | 100,229 | 100,229 | 167,514 (60,000 students) | |

| 1,545,255 | 167,410 (students) | |||

| 7,581,520 | 150,782 (2,24%) | 150,782 | 165,202 (14,420 students) | |

| 4,581,269 | 35,220 (1% of 3,522,000) | 140,880 (4% of 3,522,000) | ||

| 5,244,749 | 133,200 (3% of 4,440,004) | |||

| 7,262,675 | 130,750 (2% of 6,537,510) | 130,750 (2% of 6,537,510) | ||

| 223,652 | 10,699 | 10,699 | 125,534 | |

| 5,165,800 | 21,187 | 103,309 | ||

| 10,513,209 | 90,124 (1% of 9,012,443) | |||

| 9,957,731 | 83,206 (1% of 8,320,614) | |||

| 101,484 | 6,800 | 6,800 | 75,402 | |

| 1,317,714 | 4,100 | 4,100 | 65,886 (5%) | |

| 21,599,100 | 63,560 (students) | |||

| 84,484 | 33,305 | 33,305 | 54,909 | |

| 35,194 (2% of 1,759,701) | 52,791 (3% of 1,759,701) | |||

| 21,645 | 21,645 | 47,322 (25,677 students) | ||

| 5,455,407 | 45,500 (1% of 4,549,955) | |||

| 1,339,724,852 | 30,000 (students) | |||

| 29,441 | 22,758 (77.3%) | |||

| 2,972,949 | 28,297 (1% of 2,829,740) | |||

| 524,853 | 4,049 (1% of 404,907) | 8,098 (2% of 404,907) | 24,294 (6% of 404,907) | |

| 143,400,000 | 3,320 | 3,320 | 23,320 | |

| 513,000 | n.a. | 22,000 | ||

| 19,092 | ||||

| 16,788 | 16,788 | 16,788 | ||

| 2,209,000 | 13,943 (1% of 1,447,866) | |||

| 73,722,988 | 1,134 | 1,134 | 13,480 | |

| 2% of 660,400 | ||||

| 1,210,193,422 | 9,750 (students) | |||

| 9,457 (1% of 945,733) | ||||

| 2,711,476 | 8,000 | 8,000 | 8,000 | |

| 3,870 | ||||

| 3,500 | ||||

| 3,354 (1% of 335,476) | ||||

| 460,624,488 | 2,397,000 (934,984 already counted) | |||

| Total | 7,626,000,000 (Total World Population) | 479,607,963 (6.2 %) | 501,870,034 (6.5 % ) | 555,428,616 (7.2 %) |

Dialectal variation

A world map attempting to identify the main dialects of Spanish.

While being mutually intelligible, there are important variations (phonological, grammatical, and lexical) in the spoken Spanish of the various regions of Spain and throughout the Spanish-speaking areas of the Americas.

The variety with the most speakers is Mexican Spanish. It is spoken by more than twenty percent of the world’s Spanish speakers (more than 112 million of the total of more than 500 million, according to the table above). One of its main features is the reduction or loss of unstressed vowels, mainly when they are in contact with the sound /s/.

In Spain, northern dialects are popularly thought of as closer to the standard, although positive attitudes toward southern dialects have increased significantly in the last 50 years. Even so, the speech of Madrid, which has typically southern features such as yeísmo and s-aspiration, is the standard variety for use on radio and television. However, the variety used in the media is that of Madrid’s educated classes, where southern traits are less evident, in contrast with the variety spoken by working-class Madrid, where those traits are pervasive. The educated variety of Madrid is indicated by many as the one that has most influenced the written standard for Spanish.

Phonology

The four main phonological divisions are based respectively on (1) the phoneme /θ/ (“theta”), (2) the debuccalization of syllable-final /s/, (3) the sound of the spelled ⟨s⟩, (4) and the phoneme /ʎ/ (“turned y“),

- The phoneme /θ/ (spelled c before e or i and spelled ⟨z⟩ elsewhere), a voiceless dental fricative as in English thing, is maintained by a majority of Spain’s population, especially in the northern and central parts of the country. In other areas (some parts of southern Spain, the Canary Islands, and the Americas), /θ/ doesn’t exist and /s/ occurs instead. The maintenance of phonemic contrast is called distinción in Spanish, while the merger is generally called seseo (in reference to the usual realization of the merged phoneme as ) or, occasionally, ceceo (referring to its interdental realization, , in some parts of southern Spain). In most of Hispanic America, the spelled ⟨c⟩ before ⟨e⟩ or ⟨i⟩, and spelled ⟨z⟩ is always pronounced as a voiceless dental sibilant.

- The debuccalization (pronunciation as , or loss) of syllable-final /s/ is associated with the southern half of Spain and lowland Americas: Central America (except central Costa Rica and Guatemala), the Caribbean, coastal areas of southern Mexico, and South America except Andean highlands. Debuccalization is frequently called “aspiration” in English, and aspiración in Spanish. When there is no debuccalization, the syllable-final /s/ is pronounced as voiceless “apico-alveolar” sibilant or as a voiceless dental sibilant in the same fashion as in the next paragraph.

- The sound that corresponds to the letter ⟨s⟩ is pronounced in northern and central Spain as a voiceless “apico-alveolar” sibilant (also described acoustically as “grave” and articulatorily as “retracted”), with a weak “hushing” sound reminiscent of retroflex fricatives. In Andalusia, Canary Islands and most of Hispanic America (except in the Paisa region of Colombia) it is pronounced as a voiceless dental sibilant , much like the most frequent pronunciation of the /s/ of English. Because /s/ is one of the most frequent phonemes in Spanish, the difference of pronunciation is one of the first to be noted by a Spanish-speaking person to differentiate Spaniards from Spanish-speakers of the Americas.

- The phoneme /ʎ/ spelled ⟨ll⟩, palatal lateral consonant sometimes compared in sound to the sound of the ⟨lli⟩ of English million, tends to be maintained in less-urbanized areas of northern Spain and in highland areas of South America. Meanwhile, in the speech of most other Spanish-speakers, it is merged with /ʝ/ (“curly-tail j“), a non-lateral, usually voiced, usually fricative, palatal consonant, sometimes compared to English /j/ (yod) as in yacht and spelled ⟨y⟩ in Spanish. As with other forms of allophony across world languages, the small difference of the spelled ⟨ll⟩ and the spelled ⟨y⟩ is usually not perceived (the difference is not heard) by people who do not produce them as different phonemes. Such a phonemic merger is called yeísmo in Spanish. In Rioplatense Spanish, the merged phoneme is generally pronounced as a postalveolar fricative, either voiced (as in English measure or the French ⟨j⟩) in the central and western parts of the dialectal region (zheísmo), or voiceless (as in the French ⟨ch⟩ or Portuguese ⟨x⟩) in and around Buenos Aires and Montevideo (sheísmo).

Morphology

The main morphological variations between dialects of Spanish involve differing uses of pronouns, especially those of the second person and, to a lesser extent, the object pronouns of the third person.

Voseo

|

|

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012)

|

An examination of the dominance and stress of the voseo feature in Hispanic America. Data generated as illustrated by the Association of Spanish Language Academies. The darker the area, the stronger its dominance.

Virtually all dialects of Spanish make the distinction between a formal and a familiar register in the second-person singular and thus have two different pronouns meaning “you”: usted in the formal and either tú or vos in the familiar (and each of these three pronouns has its associated verb forms), with the choice of tú or vos varying from one dialect to another. The use of vos (and/or its verb forms) is called voseo. In a few dialects, all three pronouns are used, with usted, tú, and vos denoting respectively formality, familiarity, and intimacy.

In voseo, vos is the subject form (vos decís, “you say”) and the form for the object of a preposition (voy con vos, “I am going with you”), while the direct and indirect object forms, and the possessives, are the same as those associated with tú: Vos sabés que tus amigos te respetan (“You know your friends respect you”).

The verb forms of general voseo are the same as those used with tú except in the present tense (indicative and imperative) verbs. The forms for vos generally can be derived from those of vosotros (the traditional second-person familiar plural) by deleting the glide , or /d/, where it appears in the ending: vosotros pensáis > vos pensás; vosotros volvéis > vos volvés, pensad! (vosotros) > pensá! (vos), volved! (vosotros) > volvé! (vos) .

| Indicative | Subjunctive | Imperative | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Simple past | Imperfect past | Future | Conditional | Present | Past | |

| pensás | pensaste | pensabas | pensarás | pensarías | pienses | pensaras pensases |

pensá |

| volvés | volviste | volvías | volverás | volverías | vuelvas | volvieras volvieses |

volvé |

| dormís | dormiste | dormías | dormirás | dormirías | duermas | durmieras durmieses |

dormí |

| The forms in bold coincide with standard tú-conjugation. | |||||||

In Chilean voseo on the other hand, almost all verb forms are distinct from their standard tú-forms.

| Indicative | Subjunctive | Imperative | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Simple past | Imperfect past | Future | Conditional | Present | Past | |

| pensáis | pensaste | pensabais | pensarás | pensaríais | pensís | pensarais pensases |

piensa |

| volvís | volviste | volvíais | volverás | volveríais | volváis | volvierais volvieses |

vuelve |

| dormís | dormiste | dormíais | dormirás | dormiríais | durmáis | durmieras durmieses |

duerme |

| The forms in bold coincide with standard tú-conjugation. | |||||||

The use of the pronoun vos with the verb forms of tú (vos piensas) is called “pronominal voseo“. Conversely, the use of the verb forms of vos with the pronoun tú (tú pensás or tú pensái) is called “verbal voseo“.

In Chile, for example, verbal voseo is much more common than the actual use of the pronoun vos, which is usually reserved for highly informal situations.

And in Central American voseo, one can see even further distinction.

| Indicative | Subjunctive | Imperative | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Simple past | Imperfect past | Future | Conditional | Present | Past | |

| pensás | pensaste | pensabas | pensarás | pensarías | pensés | pensaras pensases |

pensá |

| volvés | volviste | volvías | volverás | volverías | volvás | volvieras volvieses |

volvé |

| dormís | dormiste | dormías | dormirás | dormirías | durmás | durmieras durmieses |

dormí |

| The forms in bold coincide with standard tú-conjugation. | |||||||

Distribution in Spanish-speaking regions of the Americas

Although vos is not used in Spain, it occurs in many Spanish-speaking regions of the Americas as the primary spoken form of the second-person singular familiar pronoun, with wide differences in social consideration. Generally, it can be said that there are zones of exclusive use of tuteo (the use of tú) in the following areas: almost all of Mexico, the West Indies, Panama, most of Colombia, Peru, Venezuela and coastal Ecuador.

Tuteo as a cultured form alternates with voseo as a popular or rural form in Bolivia, in the north and south of Peru, in Andean Ecuador, in small zones of the Venezuelan Andes (and most notably in the Venezuelan state of Zulia), and in a large part of Colombia. Some researchers maintain that voseo can be heard in some parts of eastern Cuba, and others assert that it is absent from the island.

Tuteo exists as the second-person usage with an intermediate degree of formality alongside the more familiar voseo in Chile, in the Venezuelan state of Zulia, on the Caribbean coast of Colombia, in the Azuero Peninsula in Panama, in the Mexican state of Chiapas, and in parts of Guatemala.

Areas of generalized voseo include Argentina, Nicaragua, eastern Bolivia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, Paraguay, Uruguay and the Colombian departments of Antioquia, Caldas, Risaralda, Quindio and Valle del Cauca.

Ustedes

Ustedes functions as formal and informal second person plural in over 90% of the Spanish-speaking world, including all of Hispanic America, the Canary Islands, and some regions of Andalusia. In Seville, Huelva, Cadiz, and other parts of western Andalusia, the familiar form is constructed as ustedes vais, using the traditional second-person plural form of the verb. Most of Spain maintains the formal/familiar distinction with ustedes and vosotros respectively.

Usted

Usted is the usual second-person singular pronoun in a formal context, but it is used jointly with the third-person singular voice of the verb. It is used to convey respect toward someone who is a generation older or is of higher authority (“you, sir”/”you, ma’am”). It is also used in a familiar context by many speakers in Colombia and Costa Rica and in parts of Ecuador and Panama, to the exclusion of tú or vos. This usage is sometimes called ustedeo in Spanish.

In Central America, especially in Honduras, usted is often used as a formal pronoun to convey respect between the members of a romantic couple. Usted is also used that way between parents and children in the Andean regions of Ecuador, Colombia and Venezuela.

Third-person object pronouns

Most speakers use (and the Real Academia Española prefers) the pronouns lo and la for direct objects (masculine and feminine respectively, regardless of animacy, meaning “him”, “her”, or “it”), and le for indirect objects (regardless of gender or animacy, meaning “to him”, “to her”, or “to it”). The usage is sometimes called “etymological”, as these direct and indirect object pronouns are a continuation, respectively, of the accusative and dative pronouns of Latin, the ancestor language of Spanish.

Deviations from this norm (more common in Spain than in the Americas) are called “leísmo“, “loísmo“, or “laísmo“, according to which respective pronoun, le, lo, or la, has expanded beyond the etymological usage (le as a direct object, or lo or la as an indirect object).

Vocabulary

Some words can be significantly different in different Hispanophone countries. Most Spanish speakers can recognize other Spanish forms even in places where they are not commonly used, but Spaniards generally do not recognize specifically American usages. For example, Spanish mantequilla, aguacate and albaricoque (respectively, ‘butter’, ‘avocado’, ‘apricot’) correspond to manteca (word used for lard in Peninsular Spanish), palta, and damasco, respectively, in Argentina, Chile (except manteca), Paraguay, Peru (except manteca and damasco), and Uruguay.

Relation to other languages

Spanish is closely related to the other West Iberian Romance languages, including Asturian, Aragonese, Galician, Ladino, Leonese, Mirandese and Portuguese.

It is generally acknowledged that Portuguese and Spanish speakers can communicate in written form, with varying degrees of mutual intelligibility. Mutual intelligibility of the written Spanish and Portuguese languages is remarkably high, and the difficulties of the spoken forms are based more on phonology than on grammatical and lexical dissimilarities. Ethnologue gives estimates of the lexical similarity between related languages in terms of precise percentages. For Spanish and Portuguese, that figure is 89%. Italian, on the other hand its phonology similar to Spanish, but has a lower lexical similarity of 82%. Mutual intelligibility between Spanish and French or between Spanish and Romanian is lower still, given lexical similarity ratings of 75% and 71% respectively. And comprehension of Spanish by French speakers who have not studied the language is much lower, at an estimated 45%. In general, thanks to the common features of the writing systems of the Romance languages, interlingual comprehension of the written word is greater than that of oral communication.

The following table compares the forms of some common words in several Romance languages:

| Latin | Spanish | Galician | Portuguese | Astur-Leonese | Aragonese | Catalan | French | Italian | Romanian | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nōs (alterōs)1,2 we (others) |

nosotros | nós3 | nós3 | nós, nosotros | nusatros | nosaltres (arch. nós) |

nous4 | noi, noialtri5 | noi | ‘we’ |

| frātre(m) germānu(m) true brother |

hermano | irmán | irmão | hermanu | chirmán | germà (arch. frare)6 |

frère | fratello | frate | ‘brother’ |

| die(m) mārtis (Classical) day of Mars tertia(m) fēria(m) (Late Latin) third (holi)day |

martes | martes, terza feira | terça-feira | martes | martes | dimarts | mardi | martedì | marți | ‘Tuesday’ |

| cantiōne(m) canticu(m) |

canción7 (arch. cançón) |

canción, cançom8 | canção | canción (also canciu) |

canta | cançó | chanson | canzone | cântec | ‘song’ |

| magis plūs |

más (arch. plus) |

máis | mais (arch. chus or plus) |

más | más (also més) |

més (arch. pus or plus) |

plus | più | mai | ‘more’ |

| manu(m) sinistra(m) | mano izquierda9 (arch. mano siniestra) |

man esquerda9 | mão esquerda9 (arch. mão sẽestra) |

manu izquierda9 (or esquierda; also manzorga) |

man cucha | mà esquerra9 (arch. mà sinistra) |

main gauche | mano sinistra | mâna stângă | ‘left hand’ |

| rēs, rĕm “thing” nūlla(m) rem nāta(m) no born thing mīca(m) “crumb” |

nada | nada (also ren and res) |

nada (neca and nula rés in some expressions; arch. rem) |

nada (also un res) |

cosa | res | rien, nul | niente, nulla mica (negative particle) |

nimic, nul | ‘nothing’ |

| cāseu(m) fōrmāticu(m) form-cheese |

queso | queixo | queijo | quesu | queso | formatge | fromage | formaggio/cacio | caș10 | ‘cheese’ |

1. In Romance etymology, Latin terms are given in the Accusative since most forms derive from this case.

2. As in “us very selves”, an emphatic expression.

3. Also nós outros in early modern Portuguese (e.g. The Lusiads), and nosoutros in Galician.

4. Alternatively nous autres in French.

5. noialtri in many Southern Italian dialects and languages.

6. Medieval Catalan (e.g. Llibre dels fets).

7. Modified with the learned suffix -ción.

8. Depending on the written norm used (see Reintegrationism).

9. From Basque esku, “hand” + erdi, “half, incomplete”. Notice that this negative meaning also applies for Latin sinistra(m) (“dark, unfortunate”).

10. Romanian caș (from Latin cāsevs) means a type of cheese. The universal term for cheese in Romanian is brânză (from unknown etymology).

Judaeo-Spanish

The Rashi script, originally used to print Judaeo-Spanish.

An original letter in Haketia, written in 1832.

Judaeo-Spanish, also known as Ladino, is a variety of Spanish which preserves many features of medieval Spanish and Portuguese and is spoken by descendants of the Sephardi Jews who were expelled from Spain in the 15th century. Conversely, in Portugal the vast majority of the Portuguese Jews converted and became ‘New Christians’. Therefore, its relationship to Spanish is comparable with that of the Yiddish language to German. Ladino speakers today are almost exclusively Sephardi Jews, with family roots in Turkey, Greece, or the Balkans, and living mostly in Israel, Turkey, and the United States, with a few communities in Hispanic America. Judaeo-Spanish lacks the Native American vocabulary which was acquired by standard Spanish during the Spanish colonial period, and it retains many archaic features which have since been lost in standard Spanish. It contains, however, other vocabulary which is not found in standard Spanish, including vocabulary from Hebrew, French, Greek and Turkish, and other languages spoken where the Sephardim settled.

Judaeo-Spanish is in serious danger of extinction because many native speakers today are elderly as well as elderly olim (immigrants to Israel) who have not transmitted the language to their children or grandchildren. However, it is experiencing a minor revival among Sephardi communities, especially in music. In the case of the Latin American communities, the danger of extinction is also due to the risk of assimilation by modern Castilian.

A related dialect is Haketia, the Judaeo-Spanish of northern Morocco. This too tended to assimilate with modern Spanish, during the Spanish occupation of the region.

Writing system

| Spanish language |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

| History |

|

| Grammar |

|

| Dialects |

|

| Dialectology |

|

| Interlanguages |

|

| Teaching |

|

Spanish is written in the Latin script, with the addition of the character ⟨ñ⟩ (eñe, representing the phoneme /ɲ/, a letter distinct from ⟨n⟩, although typographically composed of an ⟨n⟩ with a tilde). Formerly the digraphs ⟨ch⟩ (che, representing the phoneme /t͡ʃ/) and ⟨ll⟩ (elle, representing the phoneme /ʎ/ or /ʝ/), were also considered single letters. However, the digraph ⟨rr⟩ (erre fuerte, ‘strong r’, erre doble, ‘double r’, or simply erre), which also represents a distinct phoneme /r/, was not similarly regarded as a single letter. Since 1994 ⟨ch⟩ and ⟨ll⟩ have been treated as letter pairs for collation purposes, though they remained a part of the alphabet until 2010. Words with ⟨ch⟩ are now alphabetically sorted between those with ⟨cg⟩ and ⟨ci⟩, instead of following ⟨cz⟩ as they used to. The situation is similar for ⟨ll⟩.

Thus, the Spanish alphabet has the following 27 letters:

- A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, Ñ, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, X, Y, Z.

Since 2010, none of the digraphs (ch, ll, rr, gu, qu) is considered a letter by the Royal Spanish Academy.

The letters k and w are used only in words and names coming from foreign languages (kilo, folklore, whisky, kiwi, etc.).

With the exclusion of a very small number of regional terms such as México (see Toponymy of Mexico), pronunciation can be entirely determined from spelling. Under the orthographic conventions, a typical Spanish word is stressed on the syllable before the last if it ends with a vowel (not including ⟨y⟩) or with a vowel followed by ⟨n⟩ or an ⟨s⟩; it is stressed on the last syllable otherwise. Exceptions to this rule are indicated by placing an acute accent on the stressed vowel.

The acute accent is used, in addition, to distinguish between certain homophones, especially when one of them is a stressed word and the other one is a clitic: compare el (‘the’, masculine singular definite article) with él (‘he’ or ‘it’), or te (‘you’, object pronoun) with té (‘tea’), de (preposition ‘of’) versus dé (‘give’ ), and se (reflexive pronoun) versus sé (‘I know’ or imperative ‘be’).

The interrogative pronouns (qué, cuál, dónde, quién, etc.) also receive accents in direct or indirect questions, and some demonstratives (ése, éste, aquél, etc.) can be accented when used as pronouns. Accent marks used to be omitted on capital letters (a widespread practice in the days of typewriters and the early days of computers when only lowercase vowels were available with accents), although the Real Academia Española advises against this and the orthographic conventions taught at schools enforce the use of the accent.

When u is written between g and a front vowel e or i, it indicates a “hard g” pronunciation. A diaeresis ü indicates that it is not silent as it normally would be (e.g., cigüeña, ‘stork’, is pronounced ; if it were written *cigueña, it would be pronounced *).

Interrogative and exclamatory clauses are introduced with inverted question and exclamation marks (¿ and ¡, respectively).

Organizations

The Royal Spanish Academy Headquarters in Madrid, Spain.

Royal Spanish Academy

Arms of the Royal Spanish Academy

The Royal Spanish Academy (Spanish: Real Academia Española), founded in 1713, together with the 21 other national ones (see Association of Spanish Language Academies), exercises a standardizing influence through its publication of dictionaries and widely respected grammar and style guides. Because of influence and for other sociohistorical reasons, a standardized form of the language (Standard Spanish) is widely acknowledged for use in literature, academic contexts and the media.

Association of Spanish Language Academies

Countries members of the ASALE.

The Association of Spanish Language Academies (Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española, or ASALE) is the entity which regulates the Spanish language. It was created in Mexico in 1951 and represents the union of all the separate academies in the Spanish-speaking world. It comprises the academies of 23 countries, ordered by date of Academy foundation: Spain (1713), Colombia (1871), Ecuador (1874), Mexico (1875), El Salvador (1876), Venezuela (1883), Chile (1885), Peru (1887), Guatemala (1887), Costa Rica (1923), Philippines (1924), Panama (1926), Cuba (1926), Paraguay (1927), Dominican Republic (1927), Bolivia (1927), Nicaragua (1928), Argentina (1931), Uruguay (1943), Honduras (1949), Puerto Rico (1955), United States (1973) and Equatorial Guinea (2016).

Cervantes Institute

Cervantes Institute headquarters, Madrid

The Instituto Cervantes (Cervantes Institute) is a worldwide nonprofit organization created by the Spanish government in 1991. This organization has branched out in over 20 different countries, with 75 centers devoted to the Spanish and Hispanic American cultures and Spanish language. The ultimate goals of the Institute are to promote universally the education, the study, and the use of Spanish as a second language, to support methods and activities that help the process of Spanish-language education, and to contribute to the advancement of the Spanish and Hispanic American cultures in non-Spanish-speaking countries. The institute’s 2015 report “El español, una lengua viva” (Spanish, a living language) estimated that there were 559 million Spanish speakers worldwide. Its latest annual report “El español en el mundo 2018” (Spanish in the world 2018) counts 577 million Spanish speakers worldwide. Among the sources cited in the report is the U.S. Census Bureau, which estimates that the U.S. will have 138 million Spanish speakers by 2050, making it the biggest Spanish-speaking nation on earth, with Spanish the mother tongue of almost a third of its citizens.

Official use by international organizations

Spanish is one of the official languages of the United Nations, the European Union, the World Trade Organization, the Organization of American States, the Organization of Ibero-American States, the African Union, the Union of South American Nations, the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat, the Latin Union, the Caricom, the North American Free Trade Agreement, the Inter-American Development Bank, and numerous other international organizations.